.

.

.

.

…..Drawn from interviews with prominent producers, engineers, and record label executives, Michael Jarrett’s Pressed For All Time: Producing the Great Jazz Albums is filled with interesting stories behind some of jazz music’s most historic, influential, and popular recordings. In cooperation with Jarrett and University of North Carolina Press, Jerry Jazz Musician occasionally publishes a noteworthy excerpt from the book, which is now available in trade paperback.

.

.

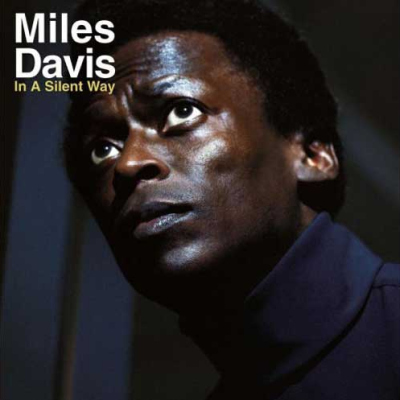

In this edition, producers Teo Macero, Bob Belden and Michael Cuscuna, and musicians Dave Holland and Joe Zawinul talk with Jarrett about the way Miles Davis’s 1969 album In a Silent Way came together.

.

.

.

.

___

.

.

Bob Belden was a saxophonist, composer, recording artist, and historian who used his production expertise to create high-concept albums of bands he led and to reissue electric jazz from Sony Music’s catalog.

Click here to read his Wikipedia biography.

.

Though Michael Cuscuna produced some of the 1970s’ most significant jazz albums, he has become the most important reissue producer in jazz history and archivist of great significance. He co-founded Mosaic Records, the premier label issuing historic multidisc collections.

Click here to read his Wikipedia biography

.

Dave Holland is a legendary bass player who leads his own group, and has played on many essential jazz recordings, including In a Silent Way.

Click here to read his Wikipedia biography

.

While a staff producer at Columbia Records, Teo Macero produced Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, Charles Mingus and several others. He was also a composer, arranger, and musician.

Click here to read his Wikipedia biography.

.

Along with Wayne Shorter, Joe Zawinul founded the seminal jazz-fusion band Weather Report. He played in bands led by Miles Davis, Dinah Washington, and Cannonball Adderley.

Click here to read his Wikipedia biography

.

.

___

.

.

Miles Davis, In a Silent Way

(1969, Columbia)

.

Teo Macero (Columbia Records)

If you go back in the history of In a Silent Way, we had something like forty reels of tape that I had mixed: two huge piles. Miles and I went through that shit, and we cut it down to eight and a half minutes on each side. Miles threw out all of the garbage. I’m sure they’re probably going to put all that stuff back in.

Miles left the studio. “That’s it,” he said – nine minutes on one side, eight and a half minutes on the other.

“Miles,” I said, “we can’t do that. Leave me alone for a little bit, and I’ll se what the hell I can do.” I built it up to make it eighteen minutes. If you listen to it very carefully – we were doing this with a razor blade, using any techniques we could muster, to bring that thing [up to LP length]. By itself – with the repeats – that’s what really makes it a work of art.

Miles later on said, “Yeah, yeah, use that piece, that shit, up front.”

“Yeah, I hear that.” It was well constructed. Miles approved everything. I rolled the tape every time we went to the studio from the beginning to end. That’s why you got a lot of wonderful little vignettes here and there. There were a lot of things that we di with Miles, even in those days. I was recording Miles on two or three different tracks. He would wander around in the studio. Later on, we put three tracks on there of Miles. I don’t recall the album, but we were doing that kind of thing. I could take what was coming direct and use that as the front, and then take another source and put a little reverb on that, and then take another one and do something else with it. We were doing a lot of experimental things in those days.

.

Bob Belden [Columbia/Legacy Reissues]

The music that came from that particular session – the actual date of In a Silent Way – was three or for eight-track reels. What Teo did was make an eight-track [copy], what they call a working master. We found out through research what exactly went down. He compiled an eight-track master that was about forty-six minutes long from In a Silent Way, which had much of the material that made it onto the album master, and much material that didn’t. (A lot of that I gave to [Bill] Laswell [for Panthalassa].) Then Teo took that forty-six minute master, and he made copies that he edited down to about thirty-something minutes. And that’s it. There weren’t forty reels of tape to go through.

.

Joe Zawinul (Keyboards, Composer)

.

Miles always like my playing from way back when I worked with Dinah Washington. He used to tell me, “You think like nobody thinks.” I didn’t know what that meant, but that’s what he said. I never actually was in his band. At the time I recorded with Miles, I was still in Cannonball’s band, but I did a lot of sessions.

Miles not only said “Bring some music,” but “Bring those tunes.” I used to go over to his house sometimes, go and play songs for him. He also said, “Nobody writes basslines like you.” I did for a few of his tunes which were going around at that time. “Bitches Brew,” I later put the basslines to it.

That particular song – which was “In a Silent Way” – he really liked, and I’d promised it to him to record. As a matter of fact, there was a fight between the Cannonball [Adderley] Band over that particular tune. I’d played it at a sound check one time – just noodling around on the piano – but I already had it all together. Nat Adderley came over and said, “Man, that is beautiful. It sounds like ‘In a Silent Way.’: So Nat gave it that title. “We’ve got to record it,” he said.

“Nat,” I said. “I cannot do that. I promised Miles to do that.” He got really upset. They said, “Man, you’re in the band almost ten years, and you give this tune out to another band?:

I said, “Listen man, I promised and that’s what it is.”

Miles and I worked on that particular tune for a couple of evenings in his house. It was [sounds out the rhythm]. It had to be like that – straight rhythm.

Michael Jarrett: So do you buy the theory that Tony played straight time because he was angry?

I don’t know, man. I loved the way Tony played and all that, but he always had a little thing on his shoulder, I thought. Unnecessarily. He was a great musician, no question, and a great guy. But there were times when…I don’t know anything about it on this particular project, but it could have been. Among the three keyboard players [Zawinul, Herbie Hancock, and Chick Corea], we didn’t talk much about it, but there were words that I don’t recall. I can’t tell you if there was anything in the rhythm section, anything that wasn’t happy.

Now, it really sounds good, but I was really disappointed in the beginning when I hears “In a Silent Way/It’s About That Time.” I thought it was boring. “In the studio we played and played in order to get two good sections and then he cuts them together? Bam. Over and out?” [On the album] there were no changes made to the melody. Nothing was re-arranged. It was just repeated too many times. It was stretched out and stretched out over and over again. Which is okay. I have nothing against that. But the total, original version of “In a Silent Way” is on my Atlantic record, Zawinul [produced by Joel Dorn]. [On Davis’s version] he took off one whole part [the head]. Otherwise, on my version the only thing I did was, when I go up [sings], I played another chord. Miles kept it on the E. That’s the only alteration; he changed one bass note.

What I really liked about those sessions was so many people without anybody stepping on another person’s foot. That’s a sign of greatness in a way. None of those guys were weak musicians. We were all into trying to kind of establish ourselves as something special. It’s an accomplishment when you have people with such security, with such self-assurance, that you don’t have to step on anybody, and it can come out as something with three ideas instead of one.

.

Dave Holland (Bass)

.

When I heard the record, I realized what had happened. There were other pieces recorded around this time, but it was surprising to me that Miles had used an extended piece for one side of the album. It was unusual, even today, for someone to use the entire side of an LP to do one tune.

Concerning the compositions, I knew that what was brought in by Joe [Zawinul] and what ended up on record were often dramatically different. The pieces were transformed and dissected in the studio. Often large sections of the tune would be discarded, and Miles might focus in on a four-bar section that he would use. There was certainly a great deal of remodeling of the compositions, which was, I know, a bit alarming to Joe [who had composed “In a Silent Way” and “It’s About That Time”]. He’d find that the composition he’d written was suddenly being completely transformed by Miles’s reworking of it. But this was one of the great touches that Miles had. He could take a composition and really make it his own in a conceptual way.

I also knew Miles talked to Tony [Williams] about the rhythm on “In a Silent Way.” I remember him going over to the drums and discussing what he as thinking about for it and so on.

There were little figures that he’d written for the bass. He said to me, “Use this. Introduce it every now and then. Then, go back to this figure.” But he’d sort of let you work out your own interpretation of what he was saying. When you land on something that he liked, he’d say, “Yeah, that’s it,” or “Do it that way,” or “That’s the direction it’s going in.” Words to that effect, but he used very few words. That was one of the great things. He really did trust the musicians and expect them to reach their own creative conclusions, a lot of the time, about the material that he was presenting to them. He wanted their input on what he presented.

.

Bob Belden (Columbia/Legacy Reissues)

.

The beat, the groove, the rhythm, it’s always there. It’s never dull. That’s why Teo could cut back and forth. If you listen to sessions prior to that one, Tony Williams was a monstrous drummer. But he showed up at the [In a Silent Way] session and saw Larry Young and John McLaughlin [in the studio] and freaked out. And that was the last time he ever played with Miles Davis. SO there’s this intense anger. It’s this withholding the ultimate Tony Williams from your idol. And the album becomes a classic.

My honest opinion, Miles put it out the way he did just to fuck with Tony. I really think so. Teo assembled it in the way you heard it on that long reel. And Miles probably said, “We don’t need this. We don’t need that, and we don’t need that.” Then, Teo went back, made the cuts, and said, “We’ve got twenty-six, twenty-eight minutes of music.” And I’m sure Miles said, “Well, make a record.” Because he didn’t care.

.

Michael Cuscuna (Mosaic Reissues)

.

Producing a set like this involves, initially, research – going through every session tape done within this particular chunk of time. Then, without relying on LP masters, remixing everything: not to change the balance of the instruments, because most of it is three-, four-, or eight-track tape, but to remove that layer of extra tape hiss and the EQ and limiting that was added during the original mastering. So remastering is, basically, to get a better sound.

In the case of this particular set, because the In a Silent Way album was so highly post-produced, with edits and repeated sections and loops inserted, we actually included the LP master in the box set and also went back to the original multi-tracks and remixed the music as the musicians originally played it. That means there are really two very, very different versions of the material in this box set.

I didn’t think Teo was using any three-machine edits at that point. That begins on Bitches Brew, where there are a lot of edits that required you, in pre-computer times, to use three machines to do a cross-fade, to transition from one tape to another. Most of the edits on In a Silent Way, I think, were hard edits. The ones you can’t hear are, for the most part, lucky in the sense that the cymbal decay hid the edit where you go from one piece to another – that sort of thing. But the thing is, even with anything as elementary as an insert, when somebody fucks up on the ending of a tune, you always record like the last eight bars of the previous person’s solo to get a suitable insert. That way there’ll be an overlap of overtone, ringing cymbals, or room sound, so that you can get an edit that no one will hear. But this stuff was all a very new process for Miles and for Teo. Miles was sort of working it out in the studio and didn’t really know how these sections were going to fit together, how it was going to work. So there are lots of times where it sounds like a bad edit, and it’s really all Teo had to work with.

I’m not sure the label knew what they had with In a Silent Way. Side-long pieces were not anyone’s idea of commercial. And this is just prior to Live/Dead coming out with a twenty-three minute “Dark Star.” I think the album was basically Miles’s own vision.

.

.

___

.

.

Listen to Miles Davis perform “In a Silent Way,” with Wayne Shorter (soprano saxophone); Chick Corea (piano); Herbie Hancock (piano); John McLaughlin (guitar); Joe Zawinul (organ, composer); Tony Williams (drums). [Columbia Records]

.

.

_____

.

.

From Pressed for All Time: Producing the Great Jazz Albums from Louis Armstrong and Billie Holiday to Miles Davis and Diana Krall. Copyright © 2016 by Michael Jarrett. Published by the University of North Carolina Press. Used by permission of the publisher. www.uncpress.unc.edu

.

.

___

.

.

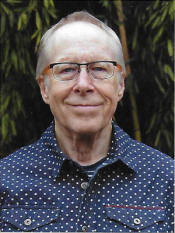

photo by Pamela Jarrett

Most of Michael Jarrett’s writing on jazz production appeared in Pulse!, Tower Records’ magazine. His day job, however, was professor of English at Penn State University (York Campus). In addition to .Pressed for All Time, his book about jazz record production, Jarrett wrote. Drifting on a Read: Jazz as a Model for Writing; .Sound Tracks: A Musical ABC; and .Producing Country: The Inside Story of the Great Recordings. He is now retired. He and his wife live in the village of Ojochal, on the southern Pacific coast of Costa Rica.

.

.

___

.

.

Click here to subscribe to the Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter

Click here to help support the continuing publication of Jerry Jazz Musician (thank you!)

.

.

.