_____

The Color of Jazz

by Bob Hecht

The late, great trumpeter Clark Terry once offered one of the most pointed, and humorous, comments about the perennial controversies in jazz over race and the perceived abilities of white versus black musicians…

He said, “My theory is that a note doesn’t give a fuck who plays it, as long as he plays it well.”

It’s not easy, or normally appropriate, to find humor in racial prejudice…but there is a little story from my life in the sixties that I do find pretty damn funny, even after all these years…

One night in the mid sixties my phone rings. It’s my friend Kinney.

“Come by tonight, if you can,” he says, “there’s someone I want you to meet. And bring some jazz records.”

Kinney and I have been friends since college, having graduated together from Seton Hall over in Jersey just a couple of years before. We both now live and work in New York; I live with my girlfriend on the Upper East Side, and he by himself down in Greenwich Village.

So before heading for the subway to go downtown, I select a few choice records to share with him: some Bud Powell, some Bird, and some Chet Baker. I have enthusiastically been turning Kinney on to some of the jazz greats I adore, and he has gradually been building a pretty good jazz collection of his own.

He opens the door to welcome me and my girlfriend, and as we enter his apartment he introduces us to a beautiful young black woman sitting on the couch.

“This is Yvonne,” he says proudly, and there’s definitely something about his tone that suggests he might just be bragging about a new sexual conquest.

It was not just Yvonne’s lovely appearance that was surprising to me. To be honest, I had not anticipated my white college friend having a black girlfriend. Interracial romances were not altogether uncommon in the Village in the mid 60’s, but still unusual enough to turn heads. And of course it was a time of ripe change in cultural and sexual mores in this country.

Kinney and Yvonne soon became a couple and moved in together. She seemed a shy and unsophisticated young woman at this point in her life, but over the next several years of their relationship she underwent a transformation. She gradually changed from a rather conventional-looking middle class girl with conventional middle class values, into a classic late 60’s hippie chick. Her tailored dresses became vintage clothes from second hand Village stores. She wore not only bellbottoms, but actual bells. Her straightened hair became an Afro, first a short one and then a huge one…

And gradually, too, her political attitudes changed. From a politically innocent and naive middle class girl, she became a strident black power advocate. And she took on some of the pretensions that often went with such transformations. She changed from a rather simple and meek young woman to a pretentious, self- absorbed and superior-sounding one—an “I have all the answers” kind of person. She became, honestly, very hard to take. Yet she seemed completely unaware of how her transformation could affect, and turn off, friends.

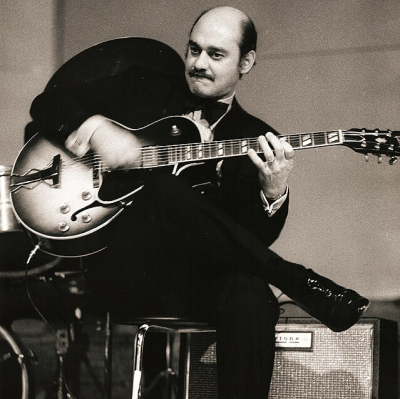

Meanwhile, Kinney’s growing love of jazz, fostered to a large degree by our friendship, also grew steadily during these years. Aside from Chet Baker, whom he said was now his most favorite player, he grew to love, and collect, records by Charlie Parker, Bud Powell, Thelonious Monk, Lester Young, John Coltrane, Miles Davis and other greats.

It never seemed that Yvonne was particularly appreciative of jazz, and in other ways as well the couple appeared mismatched. Kinney had strong intellectual leanings, and a keen desire for spiritual growth. While I turned him on to jazz, he in turn exposed me to Alan Watts, and the Zen teachings of Huang Po. I never sensed that Yvonne was on the same wavelength in that regard at all.

There came a time when their differences simply became too great. And one day, she just dumped him. While he was out at work, she unexpectedly packed her stuff and split. But not before cleaning out a good portion of his jazz record collection…and she did that in a most bizarre way, reflecting her newly found Afro-centric identity.

“She took all of my records featuring black musicians, every single one,” Kinney lamented to me later. “Now I have an exclusively all-white jazz collection.”

I didn’t say this aloud to my friend, but I guess it was kind of lucky that his most favorite musician was Chet Baker.

……

Such racial bias is, sadly, nothing new to jazz.

It’s always been ironic to me that jazz—which in many ways has a history of being one of the most egalitarian of the arts, in which how a musician is regarded usually has more to do, rightly, with the quality of his or her musicianship than the color of his or her skin—has at times been riddled with conflict over race. There have been many examples of prejudice against both black and white musicians; black musicians have often expressed frustration and anger about the music being at times co-opted by whites, and white musicians have often been frustrated and angered by claims that only blacks can ‘authentically’ play jazz.

So there is a long history of grievances, both legitimate and not, and such attitudes still do exist today, although they were much more acute back in the sixties. It was during those years, after all, that the term ‘Crow Jim’ was coined to signify the reverse racism against white musicians that was quite prevalent.

For example, back then Miles Davis often had to defend the presence of pianist Bill Evans in his band against criticism which was, as Miles characterized it, “that shit some black people put on him about being a white boy in our band. I have always just wanted the best players in my group, and I don’t care about whether they’re black, white, blue, red, or yellow. As long as they can play what I want, that’s it.”

But for the majority of jazz musicians, and its fans, the reality has been, as the great altoist Lee Konitz once commented in an interview, that “the spiritual part of this music far transcends all of those racial considerations…”

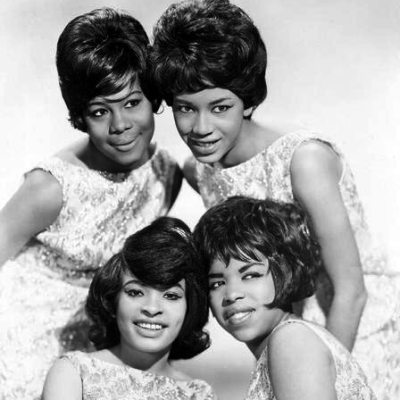

The truth is that racial integration came to jazz bandstands before it did to other, more mainstream, situations in our society. In the thirties, Benny Goodman hired Teddy Wilson, Charlie Christian and Lionel Hampton, and Artie Shaw hired Billie Holiday, years before Major League Baseball was integrated with the hiring of Jackie Robinson. And Charlie Barnet included many black musicians in his band during those years. These bandleaders did so because they valued musicianship above the prevailing discriminatory racial attitudes of the day, and often did so at considerable risk. When Barnett was warned about the impact that having blacks in his band might have on his popularity and on touring in the southern states, he reportedly replied: “Fuck the South!”

Even Charles Mingus, who was known as ‘Jazz’s Angry Man,’ and who often railed against the so-called white power structure and racism (as in his powerful, satiric piece, “Fables of Faubus”), did not hesitate to include in his various bands such great white musicians as trombonist Jimmy Knepper, saxophonists Bobby Jones and Lee Konitz, and pianist Bill Evans.

Charlie Parker hired trumpeter Chet Baker, pianist Al Haig, and trumpeter Red Rodney, and numerous other white musicians—although when Bird toured the south with the ginger-haired Rodney, he famously billed him as “Albino Red” in an attempt to circumvent segregation laws!

Parker once said about his hiring of Chet Baker, “He plays pure and simple, I like that. That little white cat reminds me of those Bix Beiderbecke records my mother used to play.”

Bix, of course, was white, but that didn’t stop Louis Armstrong from being a great admirer of his playing and a good friend.

Of course no one can honestly say they are truly color blind…to claim so can often be just another form of prejudice. It’s pretty clear that our awareness of racial differences affects our perceptions, no matter how we might try to transcend or overcome our biases.

And any idea that we might now, here in the 21st century be living in a post-racial world is patently absurd…just ask the many African Americans who are routinely harassed or jailed for driving while black, or simply for sitting in a Starbucks while black…or just ask the families of the countless young, unarmed black men gunned down by the cops sworn to protect them, or the many black or brown men and women jailed for the same crimes for which their white counterparts go free. Or the brown skinned children and parents separated at the border by the country’s current racist policies…

In the jazz world, regrettably, there are still those who take the strident position that jazz is strictly black music, and that white musicians are mere interlopers, just faux jazz artists and not the real deal…

For all of us, it’s good to remember that no less the real deal than Edward Kennedy ‘Duke’ Ellington said way back in the forties…”Jazz has become part of America. There are as many white musicians playing it as Negro…we are all working together along more or less the same lines. We learn from each other. Jazz is American now. American is the big word.”

From its beginnings jazz has been a gumbo of sorts, mixing its ingredients and flavors to form something greater than the sum of its parts…a uniquely American gumbo cooked up in the country’s melting pot.

Of course, there are always some who attempt to foul our American gumbo. As pianist Thelonious Monk once said, “They tried to get me to hate white people, but someone would always come along and spoil it.”

_____

Bob Hecht is an award-winning jazz disc jockey and fine art photographer whose photo work has been published in LensWork, Black & White, Zyzzyva and The Sun and exhibited internationally. His writing has previously appeared in LensWork and in the haiku journals Frogpond, Bottle Rockets and Modern Haiku. He and his wife live in Portland, Oregon. For twenty-five years they have been partners in On Point Productions, writing and producing marketing and training video programs. Visit his website by clicking here.

*

In an early example of black and white jazz musicians playing together, from the 1937 film Hollywood Hotel, Benny Goodman’s Quartet features pianist Teddy Wilson, vibraphonist Lionel Hampton and drummer Gene Krupa playing “I Got A Heartful Of Music”.