.

.

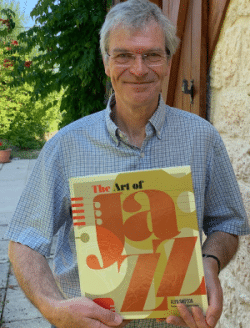

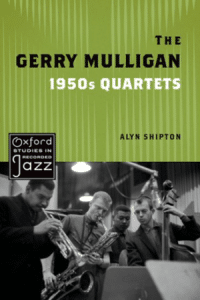

Alyn Shipton, author of The Gerry Mulligan 1950’s Quartets

.

.

___

.

.

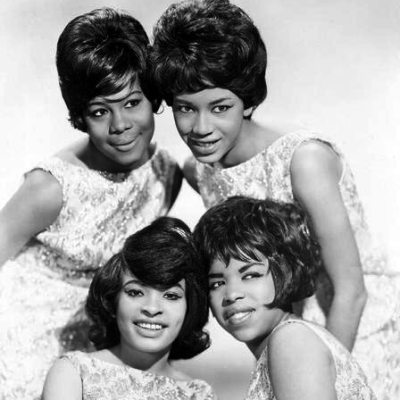

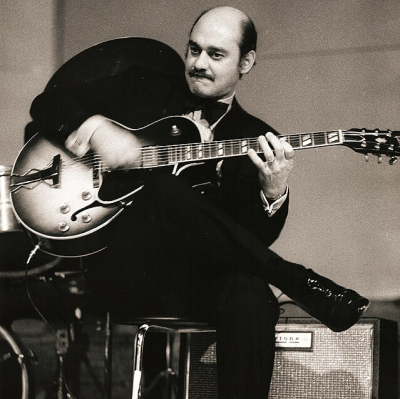

…..Long regarded as jazz music’s most eminent baritone saxophonist, Gerry Mulligan was a central figure in West Coast (“Cool”) jazz. His contributions to it were as a player, of course, but also as a significant arranger who, early in his career, worked with the likes of Claude Thornhill, Miles Davis and Stan Kenton. His “pianoless” quartet – revolutionary for its time – was one of the all-time great jazz groups, featuring the young trumpeter Chet Baker. Mulligan’s work with this quartet, and with subsequent ensembles that featured Art Farmer and Bob Brookmeyer, is the subject of noted jazz historian, writer, broadcaster and double bassist Alyn Shipton’s new book, The Gerry Mulligan 1950’s Quartets.

…..The book features original interviews with many of Mulligan’s associates, and offers a fresh take on Mulligan’s harmonic creativity. Bassist Bill Crow, an important member of several of Mulligan’s aggregations, has called the book, “a well-researched, excellently detailed study of Mulligan’s quartets. A very enjoyable read.”

…..James Gavin, award-winning music journalist and author of Deep in a Dream: The Long Night of Chet Baker, has said about the book: “Mulligan’s brainy but playful artistry gets the attention it deserves in this valuable study by Alyn Shipton. His writing teems with clear, meticulous scholarship, musical understanding, and a desire to make his subject appealing and accessible to everyone from casual jazz lovers to musicians. With Shipton’s book in hand, readers will set forth on a beautiful voyage of discovery.”

…..In this May, 2023 interview, Shipton and Jerry Jazz Musician contributing writer Bob Hecht talk about the book, and Mulligan’s unique contributions to modern jazz.

.

.

___

.

.

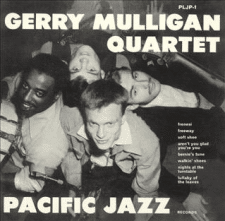

photo by William Gottlieb/Library of Congress

“The first Gerry Mulligan ‘pianoless’ quartet was formed in California in 1952 and it marked a significant departure from what had been the standard instrumentation of jazz ensembles since the dawn of the music, in which a chordal instrument generally supplied a group’s harmonic basis. There had been other isolated experiments in playing without chords, but Mulligan’s group defined a method in which trumpet (later trombone or alto saxophone), baritone saxophone, bass, and drums supplied all the necessary ingredients for a harmonically satisfying performance.”

-Alyn Shipton

.

Listen to the 1962 recording of The Gerry Mulligan Quartet, with Bob Brookmeyer (trombone), Bill Crow (bass) and Gus Johnson (drums), play “Open Country” [The Orchard Enterprises]

.

___

.

BH First of all, Alyn, congratulations on the book. I’m sure it will be recognized as an important addition to the Gerry Mulligan literature, covering as it does the unique quartets of the 1950’s, which you describe in your preface as arguably a period of his greatest innovations and lasting influence.

AS I think that is how jazz history remembers Gerry but what I’ve tried to do is to put those innovations in the context of other things that he did, which almost nobody else was doing at the same time.

BH It’s been very enjoyable, and illuminating, to read about his musical evolution, while at the same time to take breaks from the text and listen to many of the musical examples you cite in the book.

AS Well, that’s what I’ve hoped, that people would be able to have a voyage through the music and be guided through it.

BH Your book is primarily focused, as the title suggests, on his innovative quartets of the 50’s but you also include important information about his early years, as well as his work in the mid-50’s with his sextets, and the 60’s with the Concert Jazz Band. In the first section of the book, in the chapter titled “Antecedents,” you note that even in his earliest scores there was evidence of his innovative approach.

AS That’s right, particularly in his use of orchestral texture. Here’s a man who at the age of 17 was putting French horns and other interesting instruments into big band arrangements. Most of his other biographers spot that when he gets to the Claude Thornhill orchestra a bit later on but I was absolutely amazed when I unearthed the scores that he wrote as a teenager, to find those ideas were already there. And then what I think is great about Gerry, covered in the trajectory of the book, is his highly creative process of reduction. He’s reducing and reducing and reducing and making things apparently simpler but, in lots of ways, equally complex. And then gradually he starts building things back in again. One of the ways we can see that is by analyzing the pieces that he started out with in the ’40’s, rejigged in the 50’s for the quartet, and then adapted into big band arrangements again for the Concert Jazz Band. And I love the fact that he kept coming back to his compositions and finding new things to say in those arrangements.

Gerry Mulligan Quartet (Volume 1); [Pacific Jazz Records, 1952]

BH The book then follows the progression of his various quartets, the first groundbreaking “pianoless” quartet with trumpeter Chet Baker, in 1952, starting at the jazz club The Haig in Los Angeles, followed by the second iteration with trombonist Bob Brookmeyer, (as well as briefly trumpeter Jon Eardley), and then in the late 50’s with Art Farmer, and even later with Brookmeyer again. Some writers have characterized his choice of eschewing the piano as some sort of serendipitous accident, but you note that there were in fact earlier experiments by Gerry without a chordal instrument.

AS Yes, and there are two aspects to this. One is what he’d been doing in New York before he left for the west coast. I was very good friends with the British bass player Peter Ind, who told me categorically, and I quote him in the book, that he had been playing in a pianoless quartet with Mulligan in New Jersey well before he went to the west. That group, by the way, included Don Ferrara playing trumpet, who of course later became the trumpeter in one of the versions of the sextet. So there’s an example of the many connections, where things come around again and again in Mulligan’s life. The first point then, is that this wasn’t something that was completely new, he’d been trying to do it—unsuccessfully, as it turns out—before he left the east. So, secondly, when he got to the west and put the quartet together with Chet Baker, he was lucky in the sense that The Haig club was a good setting for it. Richard Bock, who was booking the bands there, hadn’t even thought of founding a record company at the time, but it was really this Mulligan band, and the sound that it created, that precipitated him founding Pacific Jazz Records.

And that’s not a bad story in terms of the way in which record companies get going. But as you mentioned, Gerry’s use of the pianoless format wasn’t quite as accidental as has often been written. I did talk to Bobby Short, who’d been playing at the club on a grand piano just before Mulligan began. That piano had been removed and put into storage. The club then offered Mulligan a little spinet piano, but he decided that he wasn’t going to put up with an inferior instrument, that it was either going to be a real piano or none at all. And so they went for the none-at-all option. The other thing about that situation was the club owner then said, okay, you can play here every week with just your pianoless quartet lineup, and there won’t be any more free-for-all jam sessions, which had been the format up to that point. And it is worth mentioning as an aside that when it was a free-for-all jam session, Ornette Coleman used to sit in there from time to time.

BH Who, of course, subsequently formed his own pianoless group!

AS Yes, exactly why I mentioned it.

BH So is it fair to conclude that there was a direct link between what Gerry was doing with that approach and what others later did?

AS I think you do find Mulligan’s influence then starts to pervade 50’s jazz. And you do get other groups including the classic Don Cherry/John Coltrane collaboration, or indeed the Ornette quartets, that played without piano.

BH And yet, as you observe in the book, this was not the first time this approach had been employed in jazz.

AS Right. I mentioned in the book that Art Farmer gave an interview to one of the African-American newspapers at the time, saying this wasn’t new. “Why man” Farmer said, “that cat (Mulligan) just picked up on something that Thelonious Monk himself started in New York a few years ago. Thelonious would just ‘stroll.’ He would ‘cool’ on the piano and leave the other guys to blow by themselves.” But what was unusual about the Mulligan group, is it set out from the outset not to have a chordal instrument.

.

A musical interlude…Listen to the 1953 recording from The Haig of Gerry Mulligan and Chet Baker (along with Carson Smith on bass and Larry Bunker on drums) play “My Funny Valentine [The Orchard Enterprises]

.

BH That first quartet was remarkable for its contrapuntal interplay. I wonder, Alyn, if you think that the lack of a chordal instrument facilitated its ability with using counterpoint?

AS Absolutely. And I’ve tried to show that with the transcriptions included in the book. There are a couple of places where you can see, in a transcription, that there are two chord sequences going on at the same time. In other words, there’s what the composer originally intended, and then there is the superimposition of a slightly different set of harmonies, which make the feeling of the music denser, even though it’s just those three voices, with baritone, trumpet and bass. “My Funny Valentine” is perhaps the best example of it, because we have the original Richard Rodgers harmonies, with the bass carrying those harmonies, but then, as the baritone comes in, Gerry is superimposing different harmonic ideas over them. If you listen to the Bach’s Six Sonatas for Violin and Obbligato Harpsichord (BWV 1014-1019) you will hear Bach doing exactly the same sort of thing harmonically—though not rhythmically—that is going on in the Mulligan quartet, with one melody line for violin, one for right-hand on the harpsichord and a bass line.

BH As I read along in your book, I was listening more closely than ever to the “My Funny Valentine” track with Gerry and Chet. Of course, that was one of the most famous recordings from that group and helped launch Baker’s fame, and his solo is justifiably praised as a thing of beauty. But as I listened, I was amazed at what Gerry does in the background. It’s very subtle but stunningly beautiful—it struck me as being almost like the sound of a small choir, with the harmony he’s creating.

AS I think this comes back to something that John Coltrane said about Thelonious Monk when he had that short period working with Monk. He used to say what’s great about Monk’s chording is that you can hear more notes in the chord than he actually plays! Coltrane could actually hear the unsounded notes in the chords that were being hinted at by Monk. And I think what you hear in Gerry’s backing to Chet, not just in this piece but in many that they played, is that he finds the ideal note to insert between the bass, which is playing the very basic harmonies of the tune, and Chet playing a melodic improvisation over the top of it. And Gerry is sounding notes that imply very many more notes than are in reality there. And his choice of those lines is the choice of an arranger—he’s thinking like an arranger, and he’s trying to make an implied harmony. That’s the phrase I use, which is about more notes than you can actually hear. But the brain kind of picks up what’s going on and substitutes the notes that are absent. So that you get, as you say, this almost choral texture from Mulligan’s playing.

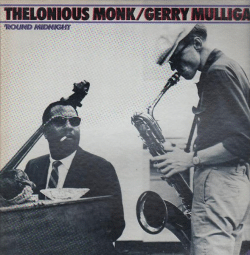

The cover of a 1982 Milestone reissue album of Monk and Mulligan recordings

BH Speaking of Monk, it was interesting to learn that Thelonious and Gerry were kind of pals for a while—they hung out together and talked about music, and that’s what led to their doing a quartet recording for Riverside Records.

AS It perhaps seems an unlikely alliance, but Riverside producer Orrin Keepnews was very proud of bringing them together for that album. And you can hear that very thing happening I just mentioned, where Monk is implying a lot more harmony than you might think, and Gerry picks up on it. That is so transparently obvious on the Monk sides, that you can then start to show, as I tried to do in the transcriptions, that it was going on all the way through the decade in Gerry’s work with his own quartet.

BH Regarding the unearthly empathy that Gerry had with Chet, Mulligan much later in life said that Baker was, “the most perfect foil to work with,” and that he’s never played with anyone who was both quicker in his melodic thinking nor less afraid to make a mistake.

AS He did say that, and it is absolutely true, when you hear the way the two of them worked together in 1952-‘53, that that was the case. And I loved the account in James Gavin’s biography of Chet, Deep in a Dream, that they used to sing the arrangements in the car on the way to the gig. So they’d actually got it all in their heads by the time they arrived. And that kind of empathy is very key to the fact that it wasn’t just a musical relationship—it was deeper than that.

BH Regarding the quartet with Bob Brookmeyer, Robert Gordon, talking about how Mulligan and Brookmeyer says they had also developed, “an almost superhuman ability to read each other’s mind.”

AS It’s particularly the case, as things developed with Brookmeyer, that Gerry and Bob had an almost instinctive arranger’s understanding of how things would work. Maybe Bob during his early days wasn’t the wonderful, lyrical, seductive improviser that Chet Baker was. But by the end of the decade, he clearly is. And I think it’s a fascinating period to look at the development of the frontline partners that Gerry had over that period, and to see just how well he worked with each of them to develop their playing, as well as his own.

.

A musical interlude…Listen to the 1959 recording of Mulligan’s Quartet, with Art Farmer (trumpet), Bill Crow (bass) and Dave Bailey (drums), play “Blueport” [Columbia/Legacy]

.

BH And then there’s the third quartet, with trumpeter Art Farmer, which you observe really galvanized the band, and you quote drummer Dave Bailey’s comment to the effect that that was the hottest of the quartets.

AS I love the Art Farmer quartet because at this point Gerry is suddenly together with somebody who’s already a mature, experienced, well-recorded improviser. And both of them find something that neither of them had found before in their previous work.

BH I read somewhere that Gerry said that the quartet with Farmer was “the most sophisticated” of the quartets…

AS Yes, I think that’s probably true. It’s sophisticated in a different way from the work with Chet, or the work with Bob. Think when this was going on, towards the end of the 50s—which is when Lee Morgan and The Sidewinder recording is happening. It’s when Blakey’s Jazz Messengers are really hitting on all cylinders. And this band competes with those despite the fact there’s no piano. For my money, the Art Farmer sides with Gerry are every bit as fantastic as the ones he made with Benny Golson & The Jazztet.

You might have noticed that I sneakily put a photo of the quartet with Art on the cover of the book, to make the point that it’s not just about the quartet with Chet.

BH Yes, I was impressed by that, because a photo with Chet would have been the obvious choice for the cover. But it’s more provocative this way. And it’s interesting to me that when Farmer joined Gerry and they played at Newport in 1958, it was just six months since Farmer was on the classic Cool Struttin’ album with Sonny Clark and Jackie McLean. So you have this guy who’s been working in a true hard bop kind of aggregation, suddenly playing counterpoint with Gerry, it’s quite remarkable.

AS Yeah, I think it is.

BH I get the impression that Gerry always wanted to be participating in musical conversation. Even when not soloing, he was very active in accompanying the other soloists.

AS Yes, and that’s true whether he’s playing piano or whether he’s playing baritone. His most successful piano ventures show that — particularly with Bob Brookmeyer, where there’s give and take, a conversational to and fro. And there’s a couple of the Concert Jazz Band pieces where he really enters into it with the rest of the band.

The cover of Mulligan’s Concert Jazz Band album ’63 [Verve]

BH It strikes me that Gerry was always creatively restless, that he always wanted to do something different, even if it was adapting earlier pieces in a different context. Following the period of the quartets, he turned to the sextet format, and then subsequently to the thirteen-piece Concert Jazz Band.

AS I love the sextet, and their recordings are some of the most joyous things that Gerry did during the decade. But I can see that there’s a very different mentality behind the Concert Jazz Band, which is somehow enlarging the idea of the Quartet and making it work within larger forces.

BH You write about how Mulligan, whether in the quartet, sextet or Concert Jazz Band, often would signal a riff pattern, which would then be picked up by other members of the group.

AS That’s right, and what they had in the Concert Jazz Band, at every stage in its development, was that there was somebody in each section who was a riff maker, whether if it was Gerry in the reads, or if it was Bob, and then there were various trumpeters such as Clark Terry who were great riff makers.

BH There are certainly great examples of that on the Live at the Village Vanguard recording, such as that version of “Blueport,” with those stop-time exchanges between Gerry and Clark, where they’re playing off city and state song titles, which is hilarious and wonderful.

AS Yes, and I think what you had with that band was a whole collection of people whose immediate response to the stimulus on stage was that they knew exactly what to do, or they could do something that would work. And you hear that especially in those Vanguard sets—I think the band just played fantastically on that session.

BH There are several allusions in your book about racial issues. As you note, Gerry often had a mixed-race band, and then I found this very interesting quote, where Mulligan says that what was going on in jazz was quite unique. He said that, “Jazz was in the forefront of having blacks and whites work together.” I think sometimes that’s often overlooked.

AS I absolutely think it is. But as you know, I didn’t hold back from Black drummer Chico Hamilton’s observations about what was going on in Central Avenue at the time that Mulligan was playing at The Haig, particularly when Lee Konitz joins the band, or when Stan Getz comes to sit in. He actually said that, “there was an ethnic thing about it,” and that the white musicians from the east coast, “all played the same way, with the same kinda groove.” And he differentiates that from how the Black musicians played, “in a different groove.” That doesn’t mean he devalues it, but he means that there were other things going on in Los Angeles, particularly in the Central Avenue scene at that time, which didn’t seep into the consciousness of the Mulligan quartet in quite the way they might have done. But we have to remember that there was this complete parallel universe going on with the Central Avenue musicians still playing in the remaining clubs there and elsewhere in Los Angeles. But The Haig was not unique, in terms of a scene where all kinds of things were going on. I think what was unique about it, and I make this point a couple of times in the book, is that several of those clubs were more mainstream orientated than modern jazz orientated. And Mulligan’s band was one of the very few interracial bands playing at that point in the early 50s.

BH Regarding the pianoless quartet format, I read a quote from Mulligan in which he said, “I didn’t have a piano because the thing I wanted to do was relate totally to the bass and serve the accompanying function with the baritone.” And you quote bassist Bill Crow as being admonished once by Gerry, saying, “You’re playing my notes!” As a bassist yourself, Alyn, how would you explain that?

AS Well, if you’re a bass player, in the regular kind of band that was going on in the 50s, you had a pianist whose role was to set out the harmonies. And what you tried to do as a bassist was to play some kind of bassline that was interesting, and not repetitive, and which didn’t hang around too much on the fundamental notes of each chord. However, in a three-voice quartet there isn’t room for that, and Gerry did not want Bill to be playing the basslines that he normally would have played with a pianist. So that’s why Gerry said, ‘you’re playing my notes,’ and that was not what the quartet needed to make its harmonic density work. What Gerry wanted from the bass player was an absolute statement of the fundamentals, or the straightforward harmonies that were supplied by the original composer.

BH I think this is a good time to mention for our readers, that while this is a very scholarly chronicle of Mulligan’s landmark groups, containing numerous musical transcriptions, one does not have to be a musician or musicologist—I am neither—to get a tremendous amount of pleasure as well as insights from reading it. Your descriptions of the recordings are very nuanced, informative, and educational.

AS Well that’s very kind of you. I know that this is going to be hard going for some readers, but the reason the transcriptions are there is to try and explain how that contrapuntal interplay developed over the years that I cover of the quartets. And during all that time, there is a refinement of the idea of how counterpoint and really sophisticated harmonic ideas can be expressed in something—that if you think about it—ought not to work! I mean, you’ve just got those three voices, so how on earth can you create such a complicated harmonic texture? But you can, and he did!

BH I wonder, as you wrote, were you conscious of engaging both the lay reader as well as the specialist musician or musicologist, and of trying to find that balance between the two types of readers?

AS Very much so. I’ve read most of the other titles in this series, The Oxford Studies in Recorded Jazz. And some of them work really well for me and have gotten me listening in a way that I might not have done before. A good example is Catherine Tackley’s book about the Benny Goodman 1938 Carnegie Hall concert, which made me go back and listen to it in a fuller way. She describes how Benny got there, and where he went afterwards, and it’s a really interesting read from that point of view, and for the lay reader the transcriptions aren’t a massive barrier to understanding all that. And so in my Mulligan book, what I was trying very hard to do was to say, “you can come along with me for this ride.” If you happen to be able to play things at all, you could sit at the piano and actually make sense of them harmonically, but at the same time I have tried not to shut out those people who don’t necessarily have the musicological training to play them or to understand all of the harmonic arguments that there are in the book.

BH Beyond the actual recordings themselves, what were your most important sources for writing this book?

AS I think the most important thing was to meet members of every version of the quartet. As you can probably tell from the text, I got on like a house on fire with drummer Chico Hamilton. And I put in the stuff where he describes how he shined shoes to buy his first snare drum, and then the fact he adapted the kit to get that very specific sound that the quartet had. I also got to know Bob Brookmeyer extraordinarily well; we made a number of BBC radio broadcasts together over the years, and I visited his house in New Hampshire several times. And then drummer Dave Bailey was also amazingly helpful. And I have to pay the greatest tribute to bassist Bill Crow, who not only gave me the kindest and really, almost undeserved quote about the book, but was a source of information and photographs and everything all the way through the whole course of the book. Bill is just one of the most amazing people on the planet, as well as being a phenomenal bass player.

.

A musical interlude…Listen to the 1949 recording of “Venus De Milo,” from the Miles Davis album Birth of the Cool [Universal Music Group]

.

BH Several years before the first quartet, Mulligan was famously a driving force in the Miles Davis Nonet, the group that became known as “The Birth of the Cool.” By the late 40’s, after he had spent some time writing for Claude Thornhill’s band—which had unique instrumentation, including French horn—Gerry brought some of those ideas over into the nonet project, which Miles Davis nominally led, but for which Mulligan composed several pieces and arranged the majority of them. As you note about the nonet, there are moments in that band that look very clearly toward his future directions as both a composer and arranger. Would you speak more to that?

AS Yes. In something like “Venus de Milo,” you can hear very much how Gerry is thinking about the small group within the context of the larger nonet. And in two or three pieces, you get the sense of his thinking about Miles’s trumpet sound and his own baritone sound blending with a relatively minimalist background. And that concept transfers straight across. So George Wallington’s composition, “Godchild,” for example, is something where Gerry had previously had a go at arranging it for Thornhill, and then pared the piece right down for the nonet. And then, of course, we hear him doing this piece again, with Chet Baker in April of 1953. That’s, as I mentioned earlier, one of the trajectories I was interested in the book was demonstrating how he could write something for a large band, then tried it out with slightly smaller bands, and ended up taking it to just the three tonal instruments in the 50’s quartet. It’s a very good example of how Mulligan developed an idea and then pared away. As I quote Bob Brookmeyer saying, “the most useful thing you could bring to a rehearsal was an eraser!” He kept taking away to create something bigger, which might seem a paradox, but I think it’s really true. I see this as a continuation of Mulligan’s extraordinary harmonic imagination through a decade.

BH It’s fascinating to me how Mulligan, throughout his career, really embraced all styles of jazz. The polyphonic textures are not far removed from New Orleans music but at the same time possess a modern feeling. In fact, someone once called his music, “good old modern music,” and Dave Brubeck supposedly said about him, “He sounds like he’s playing the past, the present and the future all at the same time!”

AS Yes, I think that’s true. He had this extraordinary ability to communicate to people whatever their jazz background was, and they could get what he was doing. Gerry seemed somehow to connect with all periods of jazz. I liked the fact that somebody whose original instincts for jazz were perhaps back with Sidney Bechet and the New Orleans players was then pulled along by the beboppers that were around him in New York at the time in the late 40’s.

BH One of the the areas of his innovation that we haven’t touched on yet is his baritone sound which was quite unique and more pleasant to listen to than a lot of the previous baritonists, and very different, of course, from Pepper Adams. I love Pepper, too, but they couldn’t be more different. Pianist Bill Charlap, who later played with Gerry, has likened his sound to that of a cello. Does that resonate for you?

AS Yes. It’s slightly deeper than the cello. One of the giveaways in this book is when Bob Weinstock was telling me that Gerry had listened to Ernie Caceres, who used to play in the Eddie Condon bands. Ernie played clarinet, but he mainly played baritone, and Gerry found something in that sound, and I think it was the fact that this was a kind of clarinet Dixieland sensibility transferred to the baritone that he really liked. And of course I have mentioned some of the other players that he liked as well, and you’re quite right about Pepper Adams who is, in a sense, the next generation of baritone players. I think what we find in Gerry is somebody much more rhapsodic than, for example, Ellington’s baritonist Harry Carney, and Gerry carries a lot of what he must have done on the alto and on the tenor into his baritone playing. He just had a concept of sound, and he managed to make the baritone sound beautiful, which is a huge achievement.

BH Thank you, Alyn, for discussing your book. There are many more aspects to it, too numerous to cover here, such as Gerry’s various one-off recording sessions with the likes of Ben Webster or Johnny Hodges, and his music for films such as the classic, I Want to Live, but we should leave those for the reader of your book to discover. It is such a rich wealth of information about Gerry Mulligan.

AS Well, thanks, Bob. It’s been a pleasure to talk to you.

.

.

Listen to the 1960 recording of Gerry Mulligan and the Concert Jazz Band performing “Black Nightgown” [Universal Music Group]

.

.

___

.

.

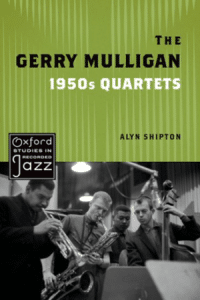

The Gerry Mulligan 1950’s Quartets

by Alyn Shipton

Click here for more information about the book

.

.

Alyn Shipton is a noted jazz historian, writer, broadcaster and double bassist. He has previously authored A New History of Jazz, The Art of Jazz, biographies on Dizzy Gillespie, Fats Waller, Cab Calloway, Bud Powell (co-authored with Alan Groves), and many others, as well as an autobiography of his life in music, On Jazz. Now, as part of the Oxford University Press series, The Oxford Studies in Recorded Jazz, he has authored The Gerry Mulligan 1950’s Quartets.

.

Click here to read our interview with Alyn Shipton concerning his recent book, The Art of Jazz

.

.

The following 23 song Spotify playlist contains examples of Gerry Mulligan’s quartets of the 1950’s.

.

.

___

.

.

This interview was hosted by Bob Hecht, and took place on May 23 & 26, 2023. Bob frequently contributes his essays, photographs, interviews, playlists and personal stories to Jerry Jazz Musician. He has a long history of producing and hosting jazz radio programs; his former podcast series, The Joys of Jazz, was the 2019 Silver Medal winner in the New York Festivals Radio Awards.

.

.

___

.

.

Click here to see the listing of many other Jerry Jazz Musician interviews

Click here for information about how to submit your poetry or short fiction

Click here to subscribe to the (free) Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter

Click here to help support the ongoing publication of Jerry Jazz Musician, and to keep it commercial-free (thank you!)

.

___

.

Jerry Jazz Musician…human produced (and AI-free) since 1999

.

.

.