.

.

.

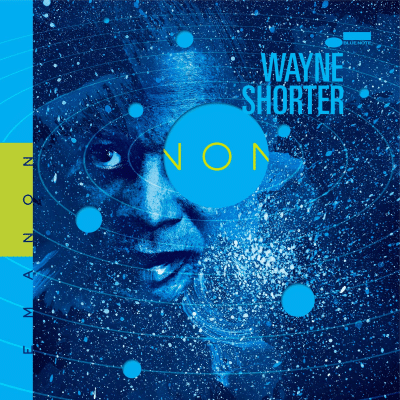

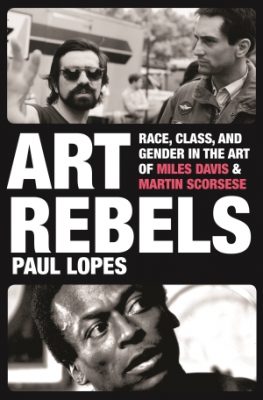

In Art Rebels: Race, Class, and Gender in the Art of Miles Davis and Martin Scorsese (Princeton University Press), Colgate University sociologist Paul Lopes refers to the post World War II era as the “Heroic Age of American Art,” a period that was “a perfect storm of changes in American art and society that led to a general burst of domestic rebellion and innovation across the arts that truly transformed how Americans viewed the nature of arts and entertainment.”

Lopes writes that experimental music and experimental film “both represent the high art road of rebellion in American music and film during the Heroic Age,” and in Art Rebels, portrays Davis and Scorsese as iconic artists whose work is connected to their “ethnic identities” and “hypermasculine ideologies” that “exposed the problematic intersection of gender with their racial and ethnic identities as iconic art rebels.”

I spoke with Paul about his book today and will publish the interview in the near future. Meanwhile, the following excerpt from Art Rebels, “Interlude,” (pages 105 – 107) introduces the book’s Part II, “The Biographical Legends of Rebels,” in which Lopes writes of how “two starkly different biographical legends emerged: one of an ‘unreconstructed’ black man who lambasted the relentless indestructible power of Jim Crow America, and another, of an ‘unmeltable’ Italian American who became, over time, a quintessential white ethnic American.”

.

.

_____

.

.

Interlude

“The Biographical Legends of Rebels” is concerned with the intersection of biography, social identity, and selfhood in the public stories of Miles Davis and Martin Scorsese. While the term biographical legend originally referred to how personal biography shaped the reputation and reception of an artist, my work expands on the scope and power of biographical legends. Such legends in the public stories of Davis and Scorsese spoke not only to their art but also to the American experience writ large. Race, ethnicity, and gender would significantly shape these two public stories. Both artists embraced their roles as active voices for their respective communities. Both artists openly connected their artistic visions with their racial and ethnic identity. And both artists expressed deeply troubling interconnections between their gender identities and their racial and ethnic identities. But crucial to understanding the power of biographical legends is to recognize how they are products of a collective telling of these biographies and their significance. Not only artists, but also critics, journalists, and others construct public stories. So, to understand the biographical legends of Davis and Scorsese, we must understand how the collective nature of the storytelling made their public stories special expressive spaces for transcoding the broader ideological conversations and imaginative interpretations that have defined the racial and gender formations in the United States from the 1950s to the present. As I mentioned in the introduction, the Heroic Age of American Art opened up an invitation for a robust new cultural politics. Public stories about American art became collective cultural politics on a large scale.

Miles Davis would become an iconic African American musician challenging the jazz art world and the broader racial formations of Jim Crow and New Jim Crow America. Martin Scorsese would become an iconic Italian American filmmaker and chronicler of the American experience. But how their respective embracing of racial and ethnic identity played out in their public stories and careers was starkly different. The unbridgeable racial divide in the American racial formation would shape far different forms of rebellion and far different responses to these art rebels. Two starkly different biographical legends emerged: one of an “unreconstructed” black man who lambasted the relentless and indestructible power of Jim Crow America, and another, of an “unmeltable” Italian American who became, over time, a quintessential white ethnic American. As Scorsese came to celebrate how white ethnic Americans were the foundation of the modern American experience, and how the American Dream eventually opens to all immigrants and social groups, Davis remained focused on how this dream was continually deferred and denied for African Americans. In other words, Davis and Scorsese gave witness in their public stories to two very distinct, if not diametrically opposed, encounters with the American experience.

The social distance and micropolitics of race relations also informed the telling and interpretation of Miles Davis’s and Martin Scorsese’s public stories. The modern jazz art world was fundamentally shaped by the social distance between white and black musicians, critics, entrepreneurs, and fans. Such a social distance existed from the microlevel of everyday interaction, to the practice of music making, to the telling of public stories. Unlike Scorsese, Davis confronted a very contentious collective telling of his public story that reflected not only his challenging of the race relations of the jazz art world and Jim Crow America but also the multimirrored interpretations of his actions, demeanors, and words. Being an “unreconstructed” black man in America was a far more perilous, and far more often misinterpreted, role than being an “unmeltable” Italian American. The public story of Miles Davis reveals the racial minefield that all African American artists navigated in a world dominated by a white racial imagination. Scorsese’s biographical legend meshed easily with the dominant narratives and self-serving delusions of post–civil rights America, while Davis’s biographical legend rubbed against such narratives and delusions. As we will see, it was the contrasting receptions of these two artists’ public stories, generated by the racial divide in America, that led to the so-called enigma of Miles Davis as the “evil genius” of jazz.

The public stories of Davis and Scorsese also showed how their gender identities were inseparable from their racial and ethnic identities. The intersectionality of race, ethnicity, and gender expressed itself powerfully in both these public stories. An intersectional feminist perspective highlights two distinct expressions of gender identity in these public stories. First, black and white masculinity in the racial imagination negotiated distinct contours of rebellion and masculinity. So black and white hypermasculinity would be experienced and interpreted differently, even while simultaneously reaffirming hegemonic masculinity and the gender formation in America. Second, the normative power of hegemonic masculinity also seemed to resolve both black and white hypermasculinity within a male gendered imagination, so that such expressions, except for a few rare moments, were rendered as taken-for-granted in music and film.

The following two chapters will show how the racial, ethnic, and gendered tropes of these iconic artists’ biographical legends speak volumes to the continuing power of the racial and gender formations in the United States during the Heroic Age of American Art. Such tropes speak not only to how such social identities shaped the actual art and lives of Davis and Scorsese but also to how these social identities acted as ciphers for interpreting these artists’ art, actions, demeanors, words, biographies, and even selfhoods. The public stories of Miles Davis and Martin Scorsese show in surprisingly, and often disturbing, ways how the racial and gender imaginations work in tandem in the collective storytelling of American art, the American experience, and the personal biographies of our most iconic artists. And as we will see, these imaginations often act to make invisible the true nature of race and gender relations as such truths are lost in translation through the power of the white and male imaginations in America.

.

Excerpted from ART REBELS: Race, Class, and Gender in the Art of Miles Davis and Martin Scorsese by Paul Lopes. Copyright © 2019 by Princeton University Press. Reprinted by permission.

.

___

.

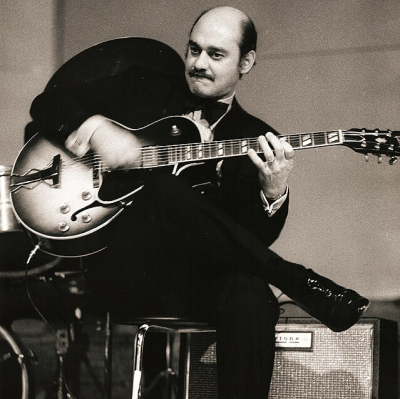

photo Mark Diorio

Paul Lopes, author of Art Rebels: Race, Class, and Gender in the Art of Miles Davis and Martin Scorsese

.

Lopes is associate professor of sociology at Colgate University, and the author of Demanding Respect: The Evolution of the American Comic Book and The Rise of a Jazz Art World

.

.

.