.

.

|

|

|

.

…..While Langston Hughes, Billie Holiday and Ralph Ellison are not known as being “religious” figures, they have, in a way, become “sacred” figures. Revered, iconic and inspirational, their essential work contributed mightily to the creative climate of twentieth-century America, and did so in the midst of complex and evolving religious currents they, along with many in their generation, had to navigate.

.

…..In 2018, three prominent religious scholars addressed this (and other topics) in provocative books:

.

…..In Langston’s Salvation: American Religion and the Bard of Harlem, Wallace Best, Professor of Religion and African American Studies at Princeton University, argues that “one cannot fully understand Langston Hughes without careful examination of his thoughts about God, the church, religious institutions and people, and matters of ultimate meaning. They are central to the corpus of his work.”

.

…..Tracy Fessenden, Director of History, Philosophy and Religious Studies at Arizona State University, describes her book Religion Around Billie Holiday as a way to “draw in more of the environing religious conditions to which [Holiday’s] genius responded: the Afro-Protestant theologies, politics, and spaces that nurtured so much of modern American sound; the white vigilante faith that passed for justice in the gallant South; the shape-shifting Jewishness of the American songbook; the gravitational pull of her contemporaries’ eclectic religious orbits; and the mythic charge of her own luminous iconicity.”

.

…..Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Theology, by Indiana University Assistant Professor in the Department of Religious Studies M. Cooper Harriss, “attempts to recast Ellison’s literary worldview in a way that proceeds from understanding invisibility to be shot through with religious and theological significance—not in a way that occludes or denies the sociological interpretation it often attracts but, rather, in the attempt to complement the materialist reading.”

.

…..When I discovered these three books toward the end of 2018, I asked myself, “What may happen if three prominent religious scholars were to get together for a discussion about their studies on the lives of Billie Holiday, Ralph Ellison and Langston Hughes? What kinds of topics will come up? Will such a discussion provide us with a better understanding about the lives of these iconic figures, and the religious worlds in which they interacted and created?”

.

…..The results are found in the following conversation, in which the scholars take up several topics, including the Great Migration, the Brown v. Board of Education ruling, and civil rights politics, and examines how the world of religion during the life and times of these iconic, “sacred” American artists helps us better comprehend the meaning of their work.

…..In the words of Professor Harriss, these books — and this discussion — helps us “to imagine not only new ways to understand our cultural figures, but also new ways of understanding religion and the world.”

.

_____

.

.

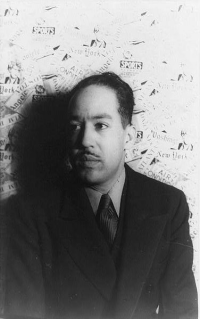

Langston Hughes, 1936

…..Hughes’s lifelong search for the meaning of salvation began that night in Kansas when he failed to see Jesus. The results of his exploration and his attempt to work out his salvation after that disappointing night, has yielded some of the most prescient thinking about religion in twentieth century literature. Hughes and his works on religion suggest a much broader reach for the history and historiography of American and African American religion. They became untethered from the conventional Protestant narratives of Christian belief and practice, making room for the perspectives, insights, and practices of the doubtful, the skeptical, the disillusioned, and the unsure, recognizing that each play a role in the structure of belief. A look to the life and work of Langston Hughes, therefore, broadens and deepens our conception of religion itself and shines a clear light on other ways we seek and sometimes find salvation.

*

From .Langston’s Salvation: American Religion and the Bard of Harlem, by Wallace Best

.

_____

.

photo by William Gottlieb/Library of Congress

Billie Holiday, c. 1947

…..If Billie Holiday had been handed a script when she arrived on the historical stage, it might have read something like this. Come from nothing, in testament to the trying, obdurate circumstance your native pluck and inborn gifts transcend. Accept the holy charge of advertising freedom; embody a tested faith in the American way of progress and opportunity and project that faith to the world. Be uplifting. Offer communion with sacred depths – as naturalness, as sexiness, as untutored genius – that casts a saving benediction on all who feel their pull. Preach a gospel of race in which all is forgiven. Make it look easy.

…..Holiday’s rise fit the script in some of the details. She could line up with its imperatives when it suited her or others who had power over her; she could also call foul. “Louis [Armstrong] made people happy with ‘Sleepy Time Down South,'” William Dufty observed just after her death. Holiday “made people miserable with ‘Strange Fruit.’ It was as simple as that.” Always she improvised, to stunning effect and sometimes at great cost. “When I was thirteen,” Holiday says in Lady Sings the Blues,

I just plain decided one day I wasn’t going to do anything or say anything unless I meant it. Not “Please, Sir.” Not “Thank you, ma’am.” Nothing. Unless I meant it.

You have to be poor and black to know how many times you can get knocked in the head just for trying to do something as simple as that.

But I never gave up trying.

*

From Religion Around Billie Holiday, by Tracy Fessenden

.

_____

.

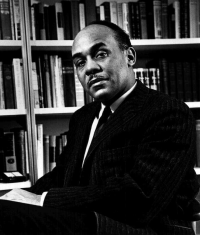

photo by United States Information Agency staff photographer

Ralph Ellison

…..Invisible Man fired a shot across the proverbial bow of prevailing literary and cultural wisdom upon its publication in 1952 by framing race within a new double consciousness. At once concerned both with specific American social and political contexts and with broader expressive legacies and orientations toward the “great” Western novels to which [Ralph] Ellison aspired, Invisible Man troubled a number of pieties surrounding race at midcentury. It ran counter not only to general assumptions about canonical literature but also to conventions of “Negro literature.”

*

From Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Theology, by M. Cooper Harriss

.

.

_____

.

.

This 90 minute telephone conversation took place on November 5, 2018, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician publisher Joe Maita

.

JJM Welcome folks…Please take a minute to introduce yourselves and your book before I pose the first question.

Tracy Fessenden,

author of Religion Around Billie Holiday

TF… I teach at Arizona State University and am the Director of the School of History, Philosophy and Religious Studies here. My background is actually in literature, so I am very interdisciplinary, and I think that is a wonderful place to approach Billie Holiday from. I wrote this book for a series called “Religion Around” (Penn State) — any number of iconic figures. As a way of placing Billie Holiday I was able in this project to look at the religious worlds she moved in, in-between, through, and with, and get a different kind of image of her in that way. I found that to be very fruitful. I am not interested in her own personal religiosity, what there might have been of it, but rather in the way in which she negotiated various religious pressures, challenges and invitations in her own life and in her music.

CH… I teach in the Department of Religious Studies at Indiana University in Bloomington, and I focus largely on American Religion and Religion and Literature. My book, Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Theology (NYU Press) came out of my interest in imagining new ways of understanding Ellison as a writer and his work. I felt that as a writer he was so often in conflict with the reigning sociological, political or aesthetic ways in which people thought of African American literature, or “Negro Literature,” which is what it was called at the time, the “Negro novel.” One of the things that I began to work on was to think about this concept of invisibility, which has become so strongly sociological, and to think of other valences about it – the metaphysical, the supernatural — and that opened up for me a number of other sources to think about, and it also opened up a way to think about Ellison, who is so often filtered through this understanding of invisibility, in new ways. Like Tracy, I am not so much interested in Ellison’s personal religious life – I don’t think there was much there in a traditional sense – but I am especially interested in the ways that these sources, these understandings that he gained as a literary figure, as an intellectual working through these cultural problems open up not only our understanding of him, but also the way it may have contributed to his cultural vision.

Wallace Best,

author of Langston’s Salvation: American Religion and the Bard of Harlem

WB… I teach in the Departments of Religion and African American Studies at Princeton University, and I also have an affiliation with the History Department, so I have my feet in many disciplinary worlds here. Langston’s Salvation (NYU Press), in a sense, is a reflection of that. I am a historian by training. My first book was on the Great Migration – I was very interested in the meanings of movement and migration – and it was during that work that I rediscovered Langston Hughes, who kept popping up in all the documents I was reading about the great mass movement of African Americans from the South to the North, particularly to Chicago. That raised a series of questions for me, the most important one being why was Langston Hughes showing up in these religious documents, or documents about migration? It was curious to me because I had come to see Langston Hughes like many others have, as someone who was wholly disconnected from religion and church, so this was very curious to me; why is Langston Hughes showing up in these gospel churches? Why is he being mentioned in sermons? From that I discovered that he had written a lot of works on religion, and I had somehow been trained not to see those works as religious works, and so that is why this book sort of emerged out of that thinking – what does it mean for someone who is allegedly not religious to write about religion?

Like Cooper and Tracy, I am not, was not, and will remain uninterested in whether or not Langston Hughes was himself religious. I was interested in his religious thought, though, and that’s why in the book I call him a “thinker about religion.” So, for me this is very much about the world of churches and religion that he lived in and that he engaged with wholeheartedly. Writing this book brought all of my interests and my training together – in its literature, its history and textual analysis – all of that was brought to bear on this study, so in some ways it looks like it is very different from my other work on migration, but in other ways it is very much in line with the work I have been doing, trying to think about and figure out lives and particular lives within the context of religious worlds. So, that is how I got to Langston’s Salvation.

TF… I want to note that in listening to Cooper and Wallace and in revisiting their works, it seems to me that what all three of us have done from our various locations is to spend time with a favorite figure, someone who really nourishes us, and to do so with the tools and the ways of seeing that we have cultivated as scholars of religion. Those tools and the ways of seeing have proven to be very fruitful. But I think it is very telling, somehow, that not one of us is concerned about the spirituality or the religiosity of the figure we are in conversation with, and I just find that remarkable, and I think it has opened up all kinds of possibilities for us. Also, I don’t know, Cooper and Wallace, if this is your experience, but it still seems to elicit some confusion or incredulity on the part of people I am in touch with when I say I have written about Billie Holiday and religion, and one of the first questions I invariably get is, “Was she religious?” or, “What religion was she?”

WB… I get the same question. The moment, Tracy, when you mentioned that you were not particularly interested in Billie Holiday’s personal faith, I anticipated that Cooper would say the same thing, and I knew I was going to say that also. I really do think that is an important intervention in religious studies, because what I say even before this book is that African American religion in particular was always written from the perspective of belief, and what I am more interested in is the way in which doubt and skepticism has also played a role in the construction of African American religion. So, what happens when we pay more attention to the voices of the doubters, the unsure, the skeptics, because they too are playing a critical role in the construction of what it means to be religious in the world. So, one doesn’t have to look at a religious figure and write one’s story from the perspective of that person’s personal beliefs. That is one way to get at the story, but another fruitful way is how that person perhaps responded to the religious worlds in which he or she lived. That is what is so fascinating about what you are doing with Billie Holiday, very explicitly, it is about the religious world in which she lived, and that is a new perspective, and I think an important one to religious studies overall. That is what I see all three of these studies doing.

TF …Certainly, yours and Cooper’s as well. The emphasis on belief, as you say, Wallace, eclipses doubt or skepticism. What it also eclipses is all the external realities of religion. If we focus on belief we are interested in people’s internal lives, and that is great as far as it goes, but we lose sight of the multiple worlds in which all these figures moved.

WB …Exactly. In as much as there is a lot to be gained by looking at personal belief, there is a lot to be lost by focusing on that. When you pull out from the study and do a sociological, anthropological and even literary analysis of the structured worlds in which these figures lived, it enriches what we can actually say about the nature of personal belief.

CH … I am also fascinated to think about the prepositions that I hear in play here: Tracy working with “religion around,” and Wallace, you discuss Hughes as a “thinker about religion.” These grammatical attempts to grapple with religious dimensions of culture – maybe not or maybe so, especially, of African American culture – highlight the embeddedness of all our figures within a larger religious world.

The other part of this conversation is one I am accustomed to having when I tell people that I “do” or work in religion and literature. When I was doing my graduate studies, it was during the high point of both the Left Behind series and The Da Vinci Code. There is a way that people are conditioned to understand how religion functions and operates within the world. What I value about the study of religion and literature – which these books are three excellent examples of – is that it works hard to reorient us away from the obvious, to help us to imagine not only new ways to understand our cultural figures, but also new ways of understanding religion and the world.

JJM …How does examining the world of religion that existed during the life and times of these artists help us understand the meaning of their work? Cooper, do you want to start the discussion on that?

CH … For me it was a way of finding, or trying to create new systems of meaning that might emerge from Ellison. So often he is read through the kind of sociological dynamics that inform a very specific period of black literary creation, black cultural creation, so taking religion—what seems like an anomalous way of thinking about Ellison—became a way of taking a stand and saying “here is this other way of understanding Ellison, a key that opens up new possibilities.” So, when invisibility is not just about marginalization – which it is, and that is very important – but when we can also open up other ways of understanding invisibility, these other ways that Ellison, as a novelist, as a thinker, is inheriting these other interpretations, these other modes of invisibility, it gives us a new way to understand his work.

TF …Cooper, after rereading Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Theology, I see again that you did a beautiful interpretation of this model for thinking about religion and iconic figures, this “religion around” idea. There are a couple of ways I could have approached this book, Religion Around Billie Holiday. I might have started with the American religious landscape of the 1930’s, 40’s, and 50’s and thought about Billie Holiday in relation to whatever I took that landscape to be. What I did instead was that I looked at her, reconstructed her biography as best I could, and then saw her as someone who in each moment was responding to her environment, which included a set of responses to her religious environment.

I was encouraged in this approach by one of my very early discoveries after agreeing to write the book on Billie Holiday, which really floored me – and it is something that is rarely mentioned in any of the discussion of her – which is that she learned to sing in a Catholic convent. She was abandoned as a kid and lived more or less on the street, and was taken up twice in her early adolescence, first at age 10 and again at almost 12, into the care of the Sisters of the Good Shepherd in Baltimore. She was sent to live in the House of the Good Shepherd for Colored Girls, which on many levels could only have been a nightmarish place, and in other ways I believe was nurturing. So she learned to sing, and she did have formal religious training every day. She sung at 6:00 AM Mass every day, and also had singing as part of her daily instruction. So she learned to sing as a form of spiritual expression and I think that that stayed with her in all of the other ways in which she interacted with her art, her form.

She didn’t grow up in what we think of as the “black church,” so she didn’t have that early introduction to singing as a kind of spiritual form or expression, and that is interesting to me, that that was not her background. But in every place I observed her range of response I saw her to be very constrained, to be very limited by all kinds of pressures around her. She could still respond as an artist, as a singer, to whatever was going on around her – and she responded, of course, in an extremely expressive way to all kinds of pressures – but also to the theology that had been inculcated in her as a very young girl. Ideas about sin, redemption, possibility, and constraint are very much a part of her sound. She could also riff a little bit on that black church sound. She knew exactly what she was doing in “God Bless the Child,” for example – which was one of Langston Hughes’s favorites – so while that was not her sound, she knew enough to incorporate that black church sound into her own work. If we have a chance to talk about it I can tell you why that song, “God Bless the Child” was also a rebuff to John Hammond, who was managing her at the time.

The other song I would put in the category of Holiday’s gritty realism, or literary naturalism if we think of her in literature, is “Strange Fruit,” of course, one of the only songs in which she really reflects in an unambiguous way on what it meant to be black in Jim Crow America. I’m certain she was aware of the thinking coming out of figures like Hughes and others about the Black Christ and what it meant to see the crucified Christ in a black body, and that was another song that she gave a particularly Catholic inflection to. But even when she was singing songs that didn’t seem to have anything to do with religion or race, I think she was singing from the formation that she received in the convent.

WB …When it comes to Hughes, one of my great findings about him is that he was a wanderer. Everywhere he went, there he was. He located himself within every context, and he just seemed to have this way of feeling a particular place, and these places had enormous impact on him. So, all of his thinking about religion can be traced back to Lawrence, Kansas, where he had his failed salvation experience.

What I say in the book is that everything he went on to write about religion somehow can be traced back where the discursively, in terms of framework or even sentence structure or in terms of ethos, back to his time in the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Lawrence, Kansas, where he, as he said, failed to see Jesus. So he goes on, throughout his life, feeling the loss of not seeing Jesus in almost every context, in some ways, so it becomes a kind of pursuit for him to not understand religion personally – because he gave up on that that night – but to understand why religion was so important, particularly to black people. “Why was church central?” was a question that he had.

He becomes fascinated by all of this, so by the time he gets to Harlem in the 1920’s, he almost immediately becomes embedded or fully connected to what I call “Harlem’s world of religion and churches.” The idea that he was disconnected from church and ideas about God is flatly wrong, if you actually read his life. Throughout his life he expressed enormous frustration that people didn’t see that religion was important to him, because they were distracted by what was also clear – that he wasn’t religious. So, this lack of personal religiosity prevented people from seeing that he actually thought this was very important for any number of reasons. This ever-changing relationship to religion to wherever he was was a lifelong attempt to understand, so when I try to read Hughes religiously, I am also trying to read the context in which he finds himself. Where he is writing this work is as important as the work itself, because he is not only looking back, he is also saying something about the moment in which he is situated. For instance, in the 1930’s, he is thinking about the Great Depression, he is thinking about the Scottsboro Boys, and a lot of this folds into his religious writing. So, Hughes is very aware of context of place, with the backdrop of his own religious experience – or failed religious experience – influencing all of this. He is the one who very much saw himself as a part of a religious world, but in a curious way. He was the “insider-outsider” of the religious worlds – not only in Harlem, but in Chicago, Washington, D.C. and everywhere he went – he made sure he was connected somehow to the religious worlds in those places, thinking about his own experiences in those contexts.

JJM …What effect did the Great Migration have on religion in the African American churches?

WB … Hughes wrote about ten poems about the Great Migration. Two of my favorites are the one he wrote in 1926, during the first phase of the Migration called “Bound No’th Blues.” “Goin’ down the road, Lawd/Goin’ down the road/Down the road, Lawd/Way, way down the road/Got to find somebody/To help me carry this load,” and he goes on. The one he is perhaps most famous for is “The One Way Ticket,” which was written in 1949, a very moving poem about the meaning of movement. “I pick up my life/And I take it with me/And I put it down in/Chicago, Detroit/Buffalo, Scranton/Any place that is North and East–/And not Dixie.” So this is about how life became unbearable for black people in the South.

Hughes was fascinated by the Migration, and firmly believed that geography is fate – where people were determined what their lives would look like. He, like many other people, had absolute faith, at first, that the North would be salvation. By the 1940’s he is writing very differently about that – it is not the promised land so much anymore, but it is still the place I need to get to if I have any hope of a better life. So the Great Migration shaped Hughes’ thinking, and one of the things to note is that a lot of his Migration poems are prayers. “Bound No’th Blues” is addressed to God, it is a prayer, and many of Hughes’ biographers and other interpreters of his work missed the point that Hughes wrote some of this work in the form of prayers – hopeful prayers about a better life, for the person in the poem who often speaks for the collective, or for black people on the move. Movement itself takes on this spiritual cadence and had deep meaning itself. The power and the freedom to be able to change place had enormous connotations of spirituality and transcendence, so Hughes saw the Migration, as many people did, in spiritual terms.

.

*

.

So, as I said, he was very aware of place, he was also very aware of movement. While he was a migrant himself, I wouldn’t call him a migrant so much as I would a wanderer, which is in the title of his 1956 biography I Wonder as I Wander, a brilliant title because it very much encapsulates his life, which has been characterized by movement, and the meaning of movement. So he is fascinated by the Great Migration, and that movement of black people has a profound and direct impact on much of his art throughout the 1940’s and 1950’s.

JJM …And on the church as well, correct?

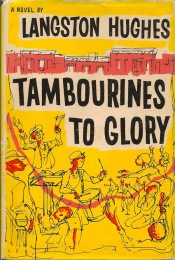

WB … Absolutely, and he is noting ways in which the Great Migration is having a profound impact on the church. His novel/play Tambourines to Glory is very much a migration text. It is about two migrant women who come to Harlem and start a church. He’s noting that churches are changing most profoundly – as St. Clair Drake said in the 1940’s, religion has a profound effect on black life, and perhaps on black religious life most profoundly. Hughes picks up on that notion and begins to write about churches in the 1940’s and 1950’s in relationship to the changes in the culture, because he is already very connected, he is there on the ground, noting various ways that the world of religion and culture in Harlem and other enclaves in the North are being shaped and re-shaped by this absolutely profound demographic shift.

By now we have enough literature to show us, to tell us, and to convince us how absolutely profound the Great Migration was. Just imagine millions of people on the move, for many years. This is changing America in a way that America hadn’t seen in quite some time – this is a large demographic shift. There is no one passively observing this – you couldn’t passively observe the Great Migration if you were in Harlem in the 1930’s and 1940’s, particularly the 1940’s because it is everywhere. You could walk out your door on a particular morning and your whole neighborhood has changed within a week. Hughes was fascinated by this, and he wrote quite a bit about the Migration, and as he begins to write about the churches, he begins to fold in his understanding of how the Migration was having an impact on black churches.

CH …Hughes arrived in Harlem in 1921?

WB …Yes, September of 1921.

CH …The story is that Ellison met Hughes at the YMCA on his first full day in Harlem, July, 1935. Ellison’s experience with migration, coming fourteen years later than Hughes, is that he arrives into something that is “in place.” Unlike Hughes, who has a decade or two under his belt in Harlem by the time Ellison arrives, although you can never quite be prepared for the experience of arrival, there are enough stories of what that can mean, and he arrives almost immediately into a political and artistic group. He comes knowing that he wants to do this – he is out of money, his scholarship is gone – so he comes from Tuskegee to New York thinking he will do a literary apprenticeship, he winds up making sculpture, he has these artistic ambitions. So Ellison, interestingly, plugs into these established, existing networks.

By the time you get to Invisible Man, it is actually a retrospective book. It is being written throughout the 1940’s and published in 1952. It is a story about a migrant and about the migration process the protagonist moves from Alabama to Harlem. It also becomes a response to or correction of Ellison’s own experiences, falling in as he did with politically-oriented writers like Hughes and Richard Wright, with whom he has contentious relationships and eventually falls out. It seems like there is a generational disconnect. So, there is something about Ellison’s arrival at that time that then goes on to affect the way that he depicts it in Invisible Man.

.

Also, getting to the question of churches or the religious dynamics of migration, especially of Harlem and of the North, it is fascinating to think that Ellison’s second novel – which he spent the second half of his life writing – does the opposite. It takes place in Georgia, and also in D.C., but his characters emerge out of Georgia. When Ellison wants to be specifically religious, when he is writing about these preachers and churches, he goes to something more “down home.” As opposed to the liberal protestant legacies of the North, Ellison takes a deep dive into the South, back into where many of the migrants came from. I think of Ellison very much as a migrant, as a product of the Great Migration, but I see Invisible Man as an attempt to question or push back against the contours of this identity and experience, to question what it means to be black and human in this new setting, in this new situation. What is the fate of this new geography? Invisible Man pushes back against some of the conventional wisdom surrounding the Great Migration. Then, when he comes to think about black religiosity as a kind of core of African American experience, he rejects the North for Georgia, for southern, black protestant Christianity.

TF …Billie Holiday’s experience was a little bit different in that she was born in Philadelphia and spent her childhood in Baltimore, which was the South but it was also on the northeast corridor, and she did move between the cities – New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Baltimore – throughout her life.

She places her arrival in New York in 1927, and she would have been twelve at the time, which is not unrealistic because she was already singing professionally in speakeasies as a very young child. But I think her experience of moving and arriving in Harlem was a little bit different from many of those whom we think of as constituting the Great Migration. At the same time, she could again incorporate that sense of movement in her sound – certainly whenever she sang the blues she was incorporating that mood of moving, of moving on, of traveling light. She knew what it was like to be in the South – she was the first black woman singer to tour with a white band, doing so with Artie Shaw in 1937 and 1938, and she didn’t like it, but she didn’t have illusions about Harlem necessarily being the Promised Land. I think she had a very wry view of what was and wasn’t possible in the North for her and black artists, and for black people in general.

JJM …The 1925 publication of Alain Locke’s The New Negro was a major event all three of you wrote about. How did the religious communities respond to this publication?

TF … I’m not sure that Billie Holiday herself was in conversation with The New Negro – at the time of its publication she would have been ten – but she arrived when there was still considerable ferment over The New Negro. I am very interested in Langston Hughes’ place in that anthology because Locke, as we know, was very nervous about jazz and blues, so Langston just talked back to him in a wonderful way that this is something marvelous to be enjoyed and pursued to the fullest. I don’t know if Cooper and Wallace would agree with me, but I think Locke’s nervousness about blues was the nervousness about the South and not being able to shake off the legacy of slavery.

CH …Absolutely.

WB …Yes, that is absolutely right.

TF … Langston was such a wonderful interpreter of music, in his contributions to that anthology and generally, and he heard many white jazz composers and musicians who saw the bluesmen with whom they were now making some sounds as throwbacks, as representing something old, something that they were moving away from. But Langston understood that, no, this Is what makes music modern, this continuous arrival of sound from the South, and I think maybe Ellison’s return to Georgia in the latter part of his life was an effort to revisit or recreate some of the complexity of that relationship between North and South that couldn’t simply be plotted on to a narrative of arrival and shaking off the old and moving into the new.

CH … It is also fascinating, Tracy, just to follow up, to think about the fact that all three of these figures are not from Alabama or Mississippi or Georgia, but from Kansas, Oklahoma and Baltimore – places away from the predominant lines of migration.

WB …I think it is somewhat ironic that Hughes is seen as one of the principal figures of the Harlem Renaissance. In some ways, as far as Locke was concerned, the movement was built around Hughes and these young artists like Hughes. Hughes would later say that yes, he was there, there was a renaissance, but the ordinary people didn’t notice it. So, he was kind of skeptical about all this literary movement from the start, but in some ways, as far as Locke was concerned, Hughes was the quintessential “New Negro” – he sort of embodied the newness.

A lot of us know the story of how the anthology came about and the survey that preceded it, and much of it is read as Locke’s “class,” “elitism,” and so forth and so on, but I think he saw it as a movement – in fact, he used that term with Hughes and others, that now we have the makings of a “movement.” So he actually saw this in somewhat spiritual terms, as a kind of spiritual emancipation of black people.

.

So, he meant “new” in several different ways. This was “new,” this was not a look to the past, meaning the nervousness about jazz and other kinds of modern forms was a nervousness about a particular way forward, not a way forward with a look to the past. So, he saw that as regressive, not progressive. While it had something to do with his elitism, it is actually much more textured than that, because he and Hughes may have disagreed about the content of this “New Negro” movement, but they agreed that it was a movement. So I try to nuance what Locke was doing there, not to dismiss him so much as this elitist Harvard philosopher who bulldozed his way in, but to see him as someone who articulated a particular vision of the “New Negro,” which was, and remains, crucial.

The New Negro anthology was very much Locke’s vision – not everybody agrees with the way in which he went about bringing that anthology about, but its staying power has something to do with his vision. He was Baha’i, not connected to a mainstream African American church, but he was very much connected to streams of spirituality. I try to suggest that his faith is animating some of what he is trying to do with that anthology, and some of the ways in which he sees the “New Negro” movement, which he sees in spiritual terms. That had been done before by the likes of Reverdy Ransom, who in 1923 wrote a poem called “The New Negro,” which he says explicitly was divinely ordained. So, there is a spiritual and a religious component to this not to be missed, and I think that it really is animating much of what Locke was up to. Now, whether or not it reached New Mount Carmel Baptist Church on the corner of 27th and Lenox, I do not know! And that would be interesting, the degree to which this movement did reach in to particular houses of worship, but I do know that some of the ministers beyond the writers and the artists themselves were thinking about this movement in spiritual terms.

TF … The poem by Reverdy Ransom, “The New Negro,” articulates a very progressive vision of the African American past, and I don’t know whether Billie Holiday ever read it, but when I hear “Strange Fruit,” I always think of her sort of talking back to Reverdy Ransom…

WB …Oh really? That’s interesting…

TF … Reading from just some of the poem; “Slavery was the chisel that fashioned him to form,/And gave him all the arts and sciences had won./The lyncher, mob, and stake have been his emery wheel,/TO MAKE A POLISHED MAN of strength and power./In him, the latest birth of freedom,/God hath again made all things new.”.

And, when I hear Billie sing “Strange Fruit,” there is nothing progressive in her view of lynching, this is not the crucible through which African American life advances to something like freedom, this is just something we need to look into the eye and take stock of, shudder and go about our lives. I am wondering now, when you talk about Ransom and Locke sharing a spiritual vision, do you think that The New Negro too was strong on this sort of progressive line. I think that was Locke’s nervousness about jazz and blues, that this was regressive, right? That we can throw this off, that we are moving into something now, like modern music, which will not be a blues production…

WB … Which is ironic, because there is nothing more modern than jazz and blues in the 1920’s…

TF … Yes, it is almost as though, because these were African American forms, they couldn’t be modern, which certain European fans were seeing something very different. This idea that everything that black America has gone through is leading somewhere is something that I don’t see Billie Holiday endorsing, and I wonder if you see The New Negro as being dependent on that kind of vision?

WB … See, that’s fascinating too. In remembering the poem, I had actually forgotten some of the content of the poem. In the post-Emancipation era, many ministers were looking back to give a theological explanation of why. Why slavery? And a lot of them came up with answers, the answer was that it was “God working…God was actually trying to bring the Negro as a race forward into a bright new future.” So, you have to give this explanation, which has to be, as far as Ransom was concerned, a providential explanation of why, which was enormously, I think, satisfying to some people. It resonated because it had to be something like that, because slavery was awful, and there were people living with those memories. So, how do you explain it? Well, God was moving black people forward, and look around you now, you have Negro writers, singers, all a witness to that progression, that we are moving forward out of a past that was quite awful, but a past that was shaping and was with some purpose, because I think that was the thing that really horrified people, that there would be no purpose in slavery, right? The explanation had to resonate.

So, by the time of the 1920’s, with this flowering of black culture, it seemed to confirm for some people that there was a purpose. You look at that past and you look at this present. What is so interesting about that though is that by the 1930’s and 1940’s that is already shaken up again, and it becomes complicated to make that kind of argument. It is ironic that Ransom would actually write that poem, being as progressive as he was politically. He was one of the first and most prominent ministers of the social gospel, but he was actually a pretty mercurial personality, so you couldn’t always pinpoint where he was going to be at any time. He did shift and change, but his reputation was as someone who was a theological modernist, and while that poem in itself is an example artistically of literary modernism, the theology embedded in it is not progressive at all, and that is the irony of it.

CH … There is an interesting corollary here in Invisible Man with the figure of the grandfather, who had been enslaved and is seen as sort of crazy, and who the invisible man had great anxiety about and says of him, “I am not ashamed of my grandparents for having been slaves. I am only ashamed of myself for having at one time been ashamed.”

Concerning the limits of the “New Negro” movement’s progressive vision, I think Ellison really gets at the ambivalence that such progressivism can’t do justice to; a reader’s understanding of the grandfather changes dramatically over the course of the novel, as Ellison challenges the older, progressive vision in a way that, I think, probably has a lot in common with something like the way Holiday sings “Strange Fruit.”

JJM … In his book on Ellison, Cooper wrote quite a bit about the impact the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education decision had on Ellison’s second novel. How did this decision impact each of your subject’s work, if at all?

CH … The very first response to it is that Ellison writes to his favorite teacher at Tuskegee, Morteza Sprague, on the day of or the day after the decision. “Well, so now the judges have found and the Negroes must be individuals and that is hopeful and good. What a wonderful world of possibilities are unfolding for the children! For me, there is still the problem of making meaning out of the past, and I guess I am lucky I described Bledsoe [the college president in Invisible Man] before he was checked out. Now I am writing about the evasion of identity, which is a characteristically American problem, which must be about change. I hope so. It has given me enough trouble.”

This decision didn’t happen overnight – this was after years of court cases and arguments that Ellison was well versed in. He had great anxiety about this decision, but it is one of those ambivalent things for him — I think he really saw it both ways. On the one hand he was, at heart, an integrationist. His vision of America is one that is framed in that way. His great anxiety, however, as someone who came out of the Deep Deuce community of Oklahoma City, as someone who wrote incredibly convincingly about black institutions like the college in Invisible Man, and as someone who would prove to be an outstanding chronicler of black church communities in the south, was the question of what will happen to these institutions now that, thankfully, there is a way forward here. But he also felt anxiety in what it means to lose these institutions that had been so involved not only in black survival, but in creating meaningful communities – schools, for instance, which is where Brown comes in.

Soon after the decision Ellison was invited to Tuskegee, where he gave a talk about how black teachers will be indispensable to integration. Ellison himself was the product of highly influential teachers like Inman Page and Zelia Breaux and segregated educational institutions that he credited with instilling confidence and providing opportunities that usually get glossed over when discussing segregated schools. He was a firm believer in the power of these segregated institutions, and while he certainly did not want the horrible, violent realities of Jim Crow segregation to continue, he harbored real anxiety that its end meant the necessary fracturing and fragmentation of these institutions and the sense of community and identity that they provided and nurtured. What will happen when they are no longer there? And, what happens when necessarily second-class citizenship becomes enforced anew without these same institutions to shore up, to protect, to nurture, to give meaning to people who confront evil systems of power?

Juneteenth is Ellison’s second novel, published posthumously in 1999. Ellison’s literary executor John Callahan edited over 2,000 pages – reportedly written over the course of forty years – and condensed it into a 368 page novel

.

That was his anxiety, and, interestingly enough, as I write in the book, this is what I attribute to the fact that he never could finish the second novel. He’s trying to do what he calls “Negro-Americanize” the novel form, yet what does it mean to be “Negro-American” when you are starting the book right around the time of Brown, when you are continuing to write it right through Montgomery, Little Rock, up through Selma, past assassinations, well into the 1970’s and into the 1980’s and 1990’s, when the notion of a kind of “Negro America” or black America or even America itself in racial terms is constantly in flux. So he can never quite nail it down. As soon as he feels he can nail something down it changes again. So, while he supported the Brown decision, I think specifically that his anxiety was about its broader implications.

.

TF … I have a comment that Cooper inspires. Cooper, I know that one of the guiding questions for your approach to Ellison is the question, using the terms that were then used about him, “Is Ellison a Negro author, or an author who happened to be a Negro?” and that you are interested in the way his whole corpus is really a navigation of that divide, or of that relation. I think that is also very true for Billie Holiday, that she resented being called a “blues singer.”

She was certainly an integrationist musically. I showed an early draft of a chapter to a friend, who was enormously helpful to me in thinking about large parts of the book, but her comment really threw me off, and it was, “Why are you spending so much time on race?” She mentioned that she grew up listening to Billie Holiday without even knowing that Billie Holiday was black. So, I was very much aware in writing this book of the question you ask of Ellison, and the question you just asked seeing Ellison wrestling with, “Am I a Negro author, or am I an author who happens to be a Negro?”

Regarding the Brown decision, I couldn’t find anything that Billie Holiday might have said about it, or in response to it. She was in Europe at the time, and she loved being in Europe because she felt very free from American drug laws, which were used to control black artists, primarily, and black drug users, at least as she experienced them. She had a lot to say about race when it came to drug laws, but not so much about segregation and integration of schools.

When there was an effort to make a movie of her life, during the time that she was still alive, and after [her autobiography] Lady Sings the Blues had come out, there was talk of the actress who would play Billie Holiday being a white actress – Ava Gardner, Lana Turner, and a couple of other names were mentioned. But she said that if you make my story anything other than the story of a Negro, then it’s not my story. So these were questions that very much animated her as well.

WB …These three artists shared a world in ways…Cooper you already mentioned that Ellison and Hughes met very early on, and [Hughes and Ellison biographer] Arnold Rampersad taught us about that initial meeting, too, and the advice Hughes gave to this young writer, and he praised Ellison’s writing very early on. And then, and Tracy you know this, there is the song, the “Song for Billie Holiday” that Hughes wrote for Billie Holiday, which is haunting. Could I read just a couple of lines of this?

TF … Yes!

WB … “What can purge my heart/of the song/and the sadness?/What can purge my heart/but the song/of the sadness?/What can purge my heart/of the sadness/of the song?” And it just goes on…

TF … It is even more haunting as it goes on.

WB … Yes, and it ends, “Voices of muted trumpet,/Cold brass in warm air,/bitter television blurred/but sound that shimmers–/Where?”

I am reading that, and when Hughes liked somebody, or he loved someone, and when he felt deeply about someone, they found their way into his art in some way. This is explicit. This is about Billie Holiday, who he greatly admired. A lot of people think this was written when she died, but this is written after her first incarceration. She died ten years later…

.

TF …Yes, I thought it was an elegy when I first read it.

WB…Right, but he is heartbroken by what he views as her demise, her long demise. Even by then, she is dying before our very eyes. But I also think that partly what he is getting at is the tragedy of her life and how very much so she never stood a chance, in some ways, so he is trying to capture both the beauty and the necessity of the song. She is a songstress, living out her life, and he captures that. So this latest episode prompts him to write this about her as if anticipating that she will die as tragically as she lived, and, he was right. Could you talk just a bit about that, Tracy? I am fascinated by this…

TF … I am too, and I am fascinated by the larger dynamic of the musicality of these writers, Langston Hughes and Ralph Ellison, and the way in which Holiday herself is taken up in so much literature. She did not write literature herself but she was a kind of literary figure, and so many people like Langston Hughes and Elizabeth Bishop and Jack Kerouac and all those who wrote about her work were absolutely infatuated with her.

Hughes’ poem is tragic, but not in the sense of a tragic performance or an act with a beginning, middle and end – he sort of knows how this is going to go. What I see that poem doing is capturing the moment, this incredible beauty and the sadness that is there, and that the shimmer is an evaporating, a departure. He knows that that’s what’s happening, but in the moment, in the presence of this sound, he is absolutely transfixed by a killing beauty. Rampersad said Hughes listened every night to “God Bless the Child” alone in his apartment over and over until the record barely held together. He had this relationship to her sound, which was the allowing of her sound to be, in a sense, the sound of his life, the sound of his longing, and that is just a gorgeous connection for me. As sad as that poem is, there is something very beautiful about that.

WB … So he is also relating to her in some ways…

TF … Yes.

WB … Oh, that is really fascinating. I had forgotten that particular connection to “God Bless the Child,” but it resonates so deeply, I can imagine Hughes doing just that. But, like I said though, he felt things so deeply, and I think this is why he was able to write so much – nothing casually passed him by. Every experience was fully felt, in some ways, so he was able to write about it. We don’t talk that much anymore about his short stories, but, how is he able to write five or six of these, sometimes, in a week? These are complete short stories that he is writing, and he is writing often. I think he is able to do that because he had an incredible ability to take it all in, and write about it.

TF … Yes, and to produce this gorgeous body of work. I think where Holiday and Hughes are similar is that they felt deeply, they could register this enormously complex set of feelings in words or in sounds, but they could also be very light. Both of them also had a very light touch – Langston’s “Semple” stories are very funny and easy to read, and, of course, Holiday threw off so many little baubles in her output – all of her Tin Pan Alley stuff is fairly light-hearted. Of course, fans know that there is a good deal there, but there is something in both of their work that says “I can do this too. I am not simply a tragic figure. I am not simply a lonely person or simply someone who feels deeply and can register the suffering in language or in sound.”

CH… This registers with Ellison as well. One of his frustrations was that people got so caught up in what they thought to be maybe the heaviness of his work, or that maybe he was – or ought to be – protesting. One of my favorite parts of his “Craft of Fiction” interview in The Paris Review is when the interviewers get on this long line of asking him, “Are you protesting this, or protesting that?” and he stops, finally, and he says, “Look, didn’t you think the book was funny?” So, this dynamic of the blues that I hear emerging from this conversation of Hughes and Holiday – which I think is also the case of Ellison – is understanding that, yes, there is this heaviness and tragedy to it, but it is also about humor, it is also about lightness and celebration and defiance in the face of that.

The other part of this, Tracy, is one of the most arresting parts to me of Religion Around Billie Holiday, where you are talking about sound. One of the connections I see here with Ellison and Hughes is that they are writers who really focus in on sound – they are highly attentive to the sound of their poems, and of their prose. During the time he is writing his second novel, when he is trying to capture the sermons, Ellison would read them out loud and record them, and he was fascinated by the way they sounded. Of course they don’t “sound” on the page, but one of the things Tracy’s book can allow us to think more fully about is not only sound itself, which you put so beautifully, but also how writers can be so transfixed by sound and try to recreate that on the page or through verse in some way.

WB … Cooper, you are right. It’s lovely to think about the attraction to sound, on its own, but connecting it to Hughes and to Holiday in this way is meaningful to me because I think now, as I am beginning to think about this relationship and thinking about this form and Hughes’ affection for Holiday, Tracy, I think you are right, I think it is about her sound, and perhaps that is something they share, this attraction to sound, this ability to hear. While Hughes wrote a lot of music, he was not a musician – he couldn’t sing, he was tone deaf, but he had this ability to hear. And, that early jazz music, he was trying to put in literary form what he was hearing – the blues. What would it look like on the page? He was fascinated by that, so he is writing all of this blues poetry, trying to capture the cadence, so when he would give readings, he would always talk about what he was trying to capture. “The Weary Blues” is the best example of that, where he is trying to capture not only the blues cadences, but something of the blues life as well.

So it is the sound of the blues that really captivates him, I think he is getting this from Carl Sandburg to some degree. I am currently writing a book called The Guiding Stars that talks about Hughes’ literary influences – chiefly being Sandburg and Walt Whitman, in that order, because that is the order he discovered them. He calls Sandburg his “guiding star.” Sandburg was also a musician – a very good musician, by the way – and he was trying to write poetry that captured the sound of music as well. So Hughes is picking some of that up from Sandburg. Hughes loved music, but he saw very early on that part of his attraction to it was the way in which he could translate it into literature. It could take literary form, and so he spent many years trying to perfect that.

TF … You think about how influential the black preaching tradition has been for black writing and American writing in general, but Langston Hughes seems to be interested in also incorporating into his literary voice the sound of the blues and the sound of these departures from black church life as well.

Cooper, “(What Did I Do to Be So) Black and Blue,” the Louis Armstrong song in Invisible Man, is so arresting. What do you make of that?

CH … One of the elements I love about it are the five phonographs playing at the same time, and that everything is just slightly off the beat, which is part of what the protagonist describes in the prologue. Also, I think another way to go with this – and Ellison was certainly interested in and fascinated by sound – is there was something about what we could call an aesthetic or a cultural dynamic that Louis Armstrong himself was the embodiment of. This is marking him out to be perhaps a little old-fashioned in the grander scheme, but Ellison never quite got bebop. There is a great anecdote Rampersad tells in his biography of Ellison about how Ellison went to an event where the Ellington band was playing, and Miles Davis was also there, and Ellison thought that he had detected some condescension from the Ellington musicians toward the bop guys. He had a secret moment of happiness over that! But there is something about the sound of Louis Armstrong’s trumpet, and of course the register of the “Black and Blue” song itself has a particular resonance, but I think for Ellison, if we want to think about sound, it is something like the opening cadence of “West End Blues.”

I like to think of Ellison in terms of form and structure, so taking these older kinds of structures, novel forms and writing them with this new kind of language, understanding himself to do a verbal equivalent of this new language that he hears emerging from someone like Louis Armstrong that doesn’t work by the time he gets to something like bop.

TF … One of the things I learned about the song “(What Did I Do to Be So) Black and Blue” is that Andy Razaf, the lyricist, wrote the lyrics at gunpoint. The gangster Dutch Schultz, a bootlegger, who was one of Joe Glaser’s cronies – Glaser was Armstrong’s manager as well as Billie Holiday’s manager – had invested in Hot Chocolates, one of these minstrel-type revues that were still popular in the 1930’s and 1940’s. During intermission, he said people are leaving, the show isn’t funny enough, so he put a gun to Razaf’s head and told him to write a funny song! On the spot, he wrote “(What Did I Do to Be So) Black and Blue.” So, that was the funny song that he wrote for the white investor in the show, and of course, Ellison and Armstrong, together, do such a beautiful job of reflecting on that production.

JJM … As literature was changing in the 1950’s – and the Brown ruling seems to be a good demarcation point – a time when, as Cooper said, Ellison was having some challenges with his own writing in the face of great change, James Baldwin was emerging, Hughes was being called to testify before the McCarthy committee, the civil rights era and new leadership in the black community was forming…There was significant societal and political change at the time. How did your subject consider their own artistic representation of “blackness” given the changing condition of the world in which they lived?

TF … In general, Billie Holiday resisted the role of representing blackness. It wasn’t one that she was particularly interested in performing. There is a stray line in an interview where someone asks her if she is a race woman, and she says “I am in the sense that…” and she gives a very limited answer. Yet if you Google “race woman” and “Billie Holiday” you will see hundreds of people saying that she was a “race woman” and that this was her priority, to work on behalf of racial equality, but it really wasn’t. She was an artist, and she herself experienced what it meant to struggle with incredible hardship and prejudice and absolutely exploitative practices on the part of her managers and handlers, but she always rose to the occasion, looked evil in the face, and met everything that came her way on equal terms, and that is how she chose to live her life. She didn’t see herself as a representative of a particular freedom movement, or a particular political movement, and I think that makes her place in the history of civil rights that much more precious to me, that, as someone who tried to meet life on its own terms she has given us so much that is indelible and eternally resonant when it comes to thinking about what it meant to be black in the 20th century.

CH … Ellison falls into a similar category, although, obviously he is quite invested in imagining his art and his craft as expression of racial identity and politics, but in a way that Tracy was just describing for Billie Holiday. He was not an activist in the way that Hughes was, or in the way Baldwin was, although Baldwin had some interesting political dynamics as well. Ellison was often criticized for this. There is a story from the mid-1970’s about an author who went to what he called a black studies library at Southern Illinois University, and asked for a copy of Invisible Man, and the librarian shot back that “Ralph Ellison is not a black writer.” There is also his guilty response, though. When he was criticized for often not being more active or on the front lines of a kind of activist approach during a time when other writers were, his response was, “I wrote Invisible Man.” After he publishes an article in Time magazine in April, 1970 titled “What Would America be Without Blacks,” he receives a letter from someone who writes a racist screed, and although Ellison’s reply letter was never mailed, his response was “I am perfectly willing to admit that you are correct, if you are willing to admit that I wrote Invisible Man.” So there is something about the art itself…

TF … Yes, the art is the answer…

CH … Yes, the art is the activism. Again, I go back and forth on that, but I think that there is, if nothing else, a kind of fidelity to that vision.

WB … Hughes would always know to say “Poetry can be the graveyard of the poet, and only poetry can be his resurrection.” By the 1960’s, he was known as being sort of conservative, or not as involved, so the depiction is that by the 1960’s he was politically irrelevant, because by the 1930’s he did have a very relevant political voice and was quite activist through his work, but by the 1940’s he is developing a much more patriotic voice. By the 1960’s he is much more behind the scenes, but he is not invisible. But that 1953 appearance before Joseph McCarthy and the sub-committee investigations had a profound impact on Hughes’ public political voice, and you note changes post-1953 where he becomes skittish about his political activism, but he doesn’t disappear. One of the things he does say, though, and this is where I think people don’t give credit to Hughes for having a life, and for also changing, He said at one point “the radical at twenty becomes the conservative at forty,” noting that some of his views did change. That did not mean though that he stood in opposition to the civil rights movement – he was very much for the cause – but by that time he is very much an artist, letting the art do the work.

Some people who write about Hughes’ lack of political activism during the 1960’s don’t understand two things. One is that, yes, some of his views had changed. He had nuanced some of his views, not radically, but he had changed the presentation of them quite a bit – but he is not invisible. Also, by that time, too, he had very much turned to the world of gospel music and is doing all this work that is basically suggesting that he is an artist and he is letting the art do the work, and that is why I think it is not inconsequential that The Panther and The Lash comes out posthumously. The book does read as a radical text for someone, but that happened after he died.

.

So Hughes is complex when it comes to his political life. There are shifts and changes in it, but you can mark significant changes post-1953 with Langston Hughes. In terms of his public presentations politically he is someone very different than the person he was in the 1930’s, and even he said that. In fact, he had to say that under duress at his meeting with McCarthy, but I think it was true. He had become a different person by the 1960’s but by no means was he invisible. He was actually the artist working behind the scenes, working a lot on the local campaigns of people like Adam Clayton Powell, Jr.

All of this is to say that it is wrong to say that Hughes was not politically active in the later years of his life. It is correct to say, though, that his approach to public political life had shifted and changed, and you have to give him credit for having a life, and for changing. That’s what he did, and I don’t know that he is to be blamed for that.

.

.

.

_____

.

.

.

Tracy Fessenden’s statement about her book, Religion Around Billie Holiday

.

…..The premise of the “Religion Around” series is that we can learn a quite a bit about any iconic figure by apprehending not only his or her own religious or spiritual life, whatever that may have been, but also the religious currents around that person and the ways he or she moved with, inside, or against them. That Billie Holiday isn’t someone we readily think of as a religious artist makes her a great test case for that idea. She didn’t have the big church sound we associate with, say, Bessie Smith or Mahalia Jackson or Aretha Franklin, because unlike them she didn’t come up in the great Afro-Protestant musical cultures that gave us gospel and blues. Yet she herself has become a kind of sacred figure. And her sound is as alive today as it ever was. It seemed worthwhile to me to think about how the spiritual currents she navigated might have shaped her life and her sound and what she and others made of them.

…..There’s an implicit pushback in the book against the notion that religion is always either liberating or oppressive. Or always anything. Religion Around Billie Holiday is in this sense a contribution to the study of lived religion, the ways people navigate the religious environments they find themselves in, and what they create or alter in those spaces in doing so, whether they identify religiously or not. Holiday was baptized Catholic and spent time in a convent reform school, and she moved in and out of various Catholic contexts over the course of her life. Catholicism wasn’t her identity so much as it was her material. To neglect this part of her story, to me, would be like overlooking Pentecostalism in the life of James Baldwin or Jewishness in the career of Philip Roth. But I also cast wider circles around Holiday to draw in more of the environing religious conditions to which her genius responded: the Afro-Protestant theologies, politics, and spaces that nurtured so much of modern American sound; the white vigilante faith that passed for justice in the gallant South; the shape-shifting Jewishness of the American songbook; the gravitational pull of her contemporaries’ eclectic religious orbits; and the mythic charge of her own luminous iconicity.

…..What’s noteworthy to me is not that her generations of admirers have seen some part of themselves, some way of being, reflected back to them in Holiday, but that she has had this effect on so many people. So many great artists have found in her music a spiritual echo of their own condition. Langston Hughes wrote a hauntingly beautiful poem about her. So did Elizabeth Bishop, somewhat resignedly, after Bishop’s companion, the heiress Louise Crane, fell madly in love with Holiday. Novelist Haruki Murakami has said what he hears in Billie Holiday is forgiveness. William Faulkner and Marianne Moore were both drawn to her. Jack Kerouac gave her a walk-on part in

Tracy Fessenden

*

Director of History, Philosophy and Religious Studies, Arizona State University

…..On the Road, and Orson Welles wanted to put her in his films. When she was just nineteen Duke Ellington cast her in the lone singing role in his 1935 film Symphony in Black: A Rhapsody of Negro Life. Composer Mary Lou Williams wrote a part of her Zodiac Suite for her. What these artists saw in Holiday was a fellow artist and an innovator, someone who, as Williams put it, “made sounds and things you’ve never heard before.” Barack Obama said that Holiday was a formative influence on him because he heard in her voice a “willingness to endure,” and in enduring to “make music that wasn’t there before.”

…..I hope readers will come away from the book with an appreciation of the influence on Billie Holiday of Catholic liturgical music and Catholic understandings of penance and grace, of the Jewish songwriting culture of Tin Pan Alley, of the echoes of black church sounds in the blues she heard and sang in brothels. That’s the “around” part of Religion Around. But music, like religion, isn’t just ambient; it’s also something we carry inwardly. I think almost everyone has an inner soundtrack. We all have songs in our heads. And spirituality is a kind of inner soundtrack, a set of inner grooves. So more than anything I hope readers of this book will be moved to listen to Billie Holiday and to listen inwardly, so that we have her music in us as we go about tending the world and making our lives.

.

.

.

_____

.

.

Wallace Best’s statement about his book, Langston’s Salvation: American Religion and the Bard of Harlem

.

…..The aim of my book was to find out what was at the root of Langston Hughes’ extensive writing on religion and why no one was talking about it in a full and comprehensive way. Hughes wrote just as much about religion as any other topic, including such topics as work, black women, racial equality and democracy, and religion – religious themes, discourses, theological frameworks, and spiritual cadences – permeate his work, even in his most famous poem, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” written in 1921. Jessie Faucet, editor at the Crisis, to whom Hughes sent the poem considered it evidence of his “spiritualness,” and Alain Locke called it Hughes’s “mystical identification with the race experience.”

I’ve known rivers,

ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

…..I argue that one cannot fully understand Langston Hughes without careful examination of his thoughts about God, the church, religious institutions and people, and matters of ultimate meaning. They are central to the corpus of his work.

…..Despite this extensive corpus of religiously-infused work, however, little sustained and comprehensive analysis of Hughes’s religious poetry has emerged. And the absence of forthright analysis of his religious work has marginalized one of the most percipient thinkers about religion in twentieth-century American literature. It has also prompted the misleading conclusions that Hughes was “secular to the bone,” “notoriously reticent about matters of religion” and “as a rule. . . stayed away from religious topics and themes.” These depictions of Hughes have contributed to the general perception that he was “anti-religious,” that is, he stood – at all times – in resolute opposition to religion and religious people, and that his poetry and other writings are a testament to that anti-religious stance. Nothing could be further from the truth, and Hughes’s own statements in his 1940 autobiography, The Big Sea, bear this out. He emphatically stated to Jean Wagner in 1958, for example, “I do not consider any of my writing anti-religious.”

…..My book, therefore, is an attempt to read Langston Hughes “religiously,” seeing him as a great “thinker about religion.”

.

.

.

_____

.

.

M. Cooper Harriss’ statement about his book, Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Theology

.

…..Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Theology argues that “invisibility” means a great deal more than meets the eye. The term has become sociological in a way Ellison remained routinely suspicious of, in a way that (to his mind) risked reducing black lives to data points and stimuli responses, not the rich and irrational experiences of people striving to live meaningfully—even irrationally—with dignity and élan in the face of harrowing systematic oppression. This book pushes beyond invisibility’s material and physical dimensions to the metaphysical. The novel’s opening line (“I am an invisible man”) invokes a story of American haunting that certainly deploys social reality, yet lingers moreso in the surplus, the excess of its significance. For this religionist, it pointed to other resonances: Paul’s “evidence of things not seen,” Cotton Mather’s Wonders of the Invisible World, the “invisible powers” of Kongo religion.

…..In this way the book attempts to recast Ellison’s literary worldview in a way that proceeds from understanding invisibility to be shot through with religious and theological significance—not in a way that occludes or denies the sociological interpretation it often attracts but, rather, in the attempt to complement the materialist reading. In the process Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Theology identifies new antecedents for the term (see Paul, Mather, and Kongo spirituality, above) as well as ways such a revision may innovate present-tense issues like drones. It also opens new vistas on Ellison’s career and context, including his friendship with Nathan Scott, his use of civil religion and original sin, parallels with thinkers like Reinhold Niebuhr and Paul Tillich, etc. Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Theology does not argue that Ellison was a “religious writer,” per se. Rather, it speaks both to the unacknowledged (or even invisible) religious and theological dimensions that shape his work and to the way his fiction and criticism theologize the racial experience of invisibility as something exceeding the rationalizations of social materialism.

.

.

.

.

This 90 minute telephone conversation took place on November 5, 2018, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician publisher Joe Maita

.

.

.