Publisher’s Note:

The publication of Arya Jenkins’ “Woman Plays Horn” is the eighth in a series of short stories she has been commissioned to write for Jerry Jazz Musician. For information about her series, please see our September 12, 2013 “Letter From the Publisher.”

For Ms. Jenkins’ introduction to her work, read “Coming to Jazz.”

_____

A Note from the Author:

I dedicate “Woman Plays Horn” to women in jazz, many of whom have been excluded from the stage as well as the canon of jazz history. These women are featured to some degree or other in Judy Chaikin’s film, The Girls in the Band, which tells the story of their travail and hardship and therefore offers up important missing pieces of jazz history. Visit The Girls in the Band website for more information.

Read this partial list like an incantation:

Geri Allen, Toshiko Akiyoshi, Lil Hardin Armstrong, Jessie Bailey, Carla Bley, Jane Ira Bloom, Joanne Brackeen, Clora Bryant, Terri Lyne Carrington, Anat Cohen, Rosalind (Roz) Cron, Peggy Gilbert, Ingrid Jenson, Jennifer Leitham, Erica Lindsay, Melba Liston, Sherrie Maricle, Marian McPartland, Mary Osborne, Ann Patterson, Terry Pollard, Carline Ray, Vi Redd, Janelle Reichman, Billie Rogers, Patrice Rushen, Maria Schneider, Hazel Scott, Viola Smith, Valaida Snow, Esperanza Spalding, Jerrie Thill, Hiromi Uehara, Nedra Wheeler, Mary Lou Williams, Anna Mae Winburn, Will Mae Wong, Helen Jones Woods, The Ada Leonard Orchestra, Ina Ray Hutton And her Melodears, Maiden Voyage, The Diva Jazz Orchestra, The International Sweethearts of Rhythm, Robynn Amy, Sheryl Bailey, Mae Barnes, Barbara Borden, Carolyn Brandy, Vi Burnside, Sharel Cassity, Carol Chaikin, Tanya Darby, Jami Dauber, Tiny Davis, Dotty Dodgion, Branda Earle, Laurie Frink, Christine Fawson, Lon Gormley, Corky Hale, Dolly Jones, Suzanne Morisette, Diana Krall, Tomoko Ohno, Lynn Milano, Lisa Parrott, Nadje Noordhuis, Rhiannon, Janet Small, Leigh Pilzer, Susanne Vincenza, Johnnie Mae Rice, Norika Ueda, Deborah Weisz, Erika Von Cleist….

WOMAN PLAYS HORN

By Arya F. Jenkins

She was born into a family of musicians. Her father had played bass in a jazz band and traveled with Dizzy until an accident had cost him his arm and his career. Getting out of a limousine that had stalled on the highway en route to a gig in Chicago, he opened the car door to get out at the wrong time, just as a truck was passing.

“C’est la vie” he always said about that, as if it meant something. He had to go on, a musician without a limb, without his instrument, because he was a man and had children and a legacy to uphold through them, but inside, where nothing touched him, he felt as torn as his shoulder had been that night. Something had shifted. Only his wife, his gentle, meek and attendant wife who saw him sitting at the edge of their bed each night head bowed counting his blessings, all but one, only she knew what its loss had cost him.

She knew and pretended not to know, a woman’s job being then, not so long ago, not to complain, only to harbor sorrows, knowledge, truth, things unseen and unheard that only passed through her. A good woman was a sieve. Viola had learned that long ago. She was the one who shouldered her children’s and her husband’s woes, their complaints and wrongs. God only knew where she put them all, she whose responsibility was to make the world seem light. It was her gift.

Carter himself was a bit deluded as to who he was, and believed, for example, that whatever his wife and children accomplished could always be traced back to him. Despite the fact nobody could prepare okra, collard greens, cornbread, hushpuppies and gravy or barbecued chicken like Viola, nobody, every time she even served grits, he would look around himself, head raised proudly, waiting for congratulations — as if he was responsible!

When Carter gazed at his Viola, she who had never given him an ounce of trouble and never made him feel anything but pride, he knew he was blessed and had nothing to complain about, despite how empty and hard he felt inside. Since the accident, he found it hard to feel grateful, hard not to focus on what he did not have, rather than what he did have. He kept reminding himself he had his wife, his sons, his daughter, and didn’t that mean everything? He told himself it sure did, but he did not feel it.

Carter’s two sons were talented musicians — Rufus especially, on the piano, good enough to do side gigs and make money at it his whole life, if he wanted. The other — George, was more impelled toward business, but he was all right on bass, could hold his own as a professional too. But it was Frances, his youngest, the one he had nicknamed Chicklet, shortening it to Chi — after her all-consuming passion when she was a kid — it was she who was incomparable, simply wicked on her instrument, the horn. It was all Carter thought about whenever he set eyes on her. And while Viola was proud of her daughter’s musical skills as well, what she held closest to her, almost like a feminine trophy, was the fact the child was a knockout, exquisitely chiseled, with an immaculate complexion.

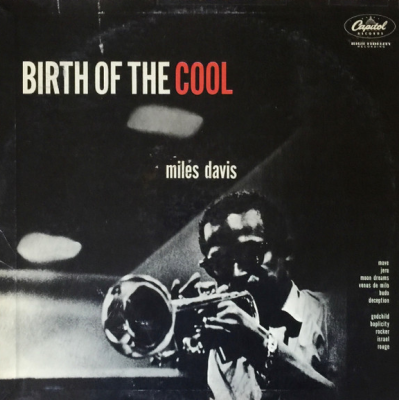

Carter never came out and told Chi how fantastic she was musically. He knew better than that. For one thing, it would have been out of character for him to do this. But to himself, he said the inviolate, the impossible thing — she was better than Miles, better than him.

Viola knew it too, instinctively, the way she knew all things. When Chi was in her teens, practicing, Carter and Viola would sit together on the divan attending to her lesson, both of them floating up to heaven on her sound. None of their other kids, in fact, no one else Carter had ever played with had elicited that from him, and he had known and played with some greats. Chi had the ability to weave a story in a single breath, communicating an uncanny intelligence through her horn, sending the listener into a rare orbit.

“Is it me?” Carter would say, turning to Viola, and she would shake her head, concurring, “Hmmm mmm, Nothing like it.”

Like Miles, Chi also composed her own tunes. Like Miles, she had a distaste for the disingenuous, and for fawning, undiscriminating fans, people who did not know the music or even a tune she was playing, or who did not call a thing by its name, by what it was. She would show up for gigs in ripped jeans, her Afro orange yellow hair splayed out every which way.

She’d worn her hair like that since she was 13, when she announced to her parents, “I don’t have time to dress up or do my hair like a lady. It distracts me from my music.” And while her parents both winced when they saw what she put on whenever she stepped out, they let it go because they realized too, the music was the important thing.

Whenever the church ladies got on Viola’s case about the way Chi looked, Viola would hit back with, “My baby dresses like a rebel but plays like an angel.”

Chi stood out, and her playing stood out and that was what she wanted. She was not going to be another Vi Redd, a musician who, however brilliant, had been forced to remain in the shadows just because she had been female in an all male world back when. Her daddy had performed with Vi when she had played alto sax and sung with Dizzy. As if her amazing talent on the alto sax had not been enough, Dizzy had made Vi dress in sequins — maybe to distract people from registering how damn good she was. Her daddy had once said, “Vi was right up there with Charlie Parker.”

Carter told his stories about the music business to Chi mainly, because she was the one ate them up, the one truly hungry to know more. His boys just weren’t all that interested.

Chi had been shocked to learn Vi Redd had only cut two, maybe three records in her lifetime. “Should have been more,” she said. It made her angry.

“Should have been,” Carter agreed with her.

Even though it was no longer the 60s, 70s or even 80s, even though things had changed for women in the business, the story of Vi Redd, as Chi understood it, always served as a reminder to her of how things still could be, of what shadows lurked behind the curtains, what shit she might have to encounter for being a woman who was not only that good, but independent. She didn’t need anybody to tell her what was good, not even when she was good. She knew it. Shit, just because of what had happened to Vi Redd, she herself would never put on sequins. Probably never have a husband or kids either, as they would only detract from the music.

Vi’s story served as an example of how things had once been, and Chi was glad not to have been born into that time, but into the future, which held so many more possibilities. She wanted to be the best horn player ever, to surpass even Miles. She would never turn her back to an audience or do drugs like Miles had. She was not arrogant, or foolish like that. She wanted to be a better musician, that’s all, and dedicate her life to that. This was how Chi thought at 15, even before getting to Juilliard.

After graduating Juilliard, Chi moved into a cool apartment on Banks Street, and found time between gigs to teach music to high school kids in Harlem as a volunteer. Her life seemed to be on an upward spiral. She was starting to gain a following at different clubs, and critics were starting to notice. Her father and mother, always on the phone with her, always keeping tabs on Chi, their prize, could not have been prouder. In-between the happiness, the cloud Chi was sailing on, was a steady gnawing in her gut, her urge her to keep growing.

Then, late one night, leaving a gig at the Paris Club, a new club that had opened in the old meat-packing district, Chi decided to walk home along Hudson Street. It was not a long walk, and all she had to carry was her horn in its case, although it was late to be out alone. It occurred to her more than once that it was too late, but she dismissed it. She was an experienced city dweller, a smart, savvy woman, a pro, and at home in what many considered a cold, hard world, one that until then had been only welcoming to her.

It never occurred to Chi to hail a taxi, it was so beautiful out and she had played so well that night, and felt so good, but when a black sedan pulled up alongside her and a tinted window rolled down, and she could see the wolfish, handsome grin of a stranger, someone she had seen in the club, someone whose eyes had remained masked behind sunglasses only until that moment, she turned and smiled at him inadvertently, even as that smile sent a warning twinge to her gut.

“Hey, my name is Eddie,” the man said. “You play a mean horn, lady. Would you flatter me and let me take you wherever you are going.”

“That’s all right, man. Thanks anyway.” She waved him off politely and kept walking.

He kept following, still smiling, “I’m not going to take no for an answer. A young good-looking lady like yourself should not be walking alone at this hour. Let me take you home,” he said, ever so considerately. “Where you headed, the West Village? I’m headed there too. Please. Allow me.” Chi was starting to feel like she had just stepped into a romantic movie scene, he was so relentless and charming.

She would never wholly be able to explain to herself why exactly she gave in to his request. He stopped the car and turned out his palms to her as if such a gesture surely proved him innocent. She opened the side door, propped her instrument in its case gingerly in back, then stepped into the passenger seat, securing a belt around herself. Then the doors locked automatically, and the windows went up.

The man took off so fast, her head jerked back. “What the…” escaped her, although he moved faster than her denial could flee. Was this a bad dream? A series of turns and she found herself alone with him in animal-scented darkness, stopped nowhere, nowhere that she knew anyway. He gripped the wheel with large gnarly hands, ugly for a young man’s, and she saw his profile indelibly then, a mulatto with amber curly hair, and dirty cuffs peeking out of a worn navy jacket. “It’s bitches like you that have ruined us,” he said and back slapped her. “You need a lesson.”

She tried to fight him, but he had parked and was on her in an instant, grabbing hold of her hair — her hair of all things, she thought then — yanking it back just as the passenger seat released and they both fell back, and he pulled out a switchblade and began slicing her locks while riding her like a pony, giving himself a hard on. There was no way she could get away, but as he raised himself momentarily, she slid under him and booted the front windshield hard as she could — once, twice. It cracked and popped and she heard “Hey!” from the outside, just as she felt the knife slice the side of her cheek, as if he was intent on taking her very face. “Bitch,” she heard before utter darkness enveloped her.

He could have killed her, should have. Not being able to ascertain anything more than the fact he was high on drugs, another mad musician, authorities failed to ascribe any other motivation to what he had done. She was unconscious when he pushed her out the car door and took off, although not before a witness in the parking lot took down his plates. The broken windshield made him easy to find anyway.

The doctors that worked on Chi’s face did a good job, although the right side of her face was twice its size for days. First thing Chi thought of when she started to come to was what had happened to her trumpet, a wonderment that was instantly replaced by the shock of dull pain down her face, and the memory of what had caused it so thorough and sharp that she felt she might pass out from recollecting. In her drug haze and delirium, she alternately saw her Getzen 900S, the best horn she had ever owned or played, and her attacker’s wretched visage. One image made her smile, the other, nauseous. Then she thought she saw faces she knew before her, but chose the oblivion of sleep over a reality she could not yet fathom.

Another time, barely conscious, she swore she could smell her mother’s cooking, and another time a needle’s sting on her arm woke her. She did not realize yet these sensory extremes signaled a life to come that would be dominated by the experience of pain intermingled with beauty, as she suffered the repercussions of what had transpired. Every time she would blow into her horn, she would feel the line of brutality down her face and have to transform what it made her recall somehow, somehow diminish its power through music, through playing.

“Hey. Hey,” she heard the familiar, musical voice of her brother and flipped her eyelids open letting her gaze rest on Rufus, who stood beside the bed, his perspiring hands fumbling for hers, his long lashes beating ever so slightly as he gazed at her worriedly.

“You’re lucky to be alive, sis,” he said, his large eyes welling.

“Don’t I know it,” she heard herself reply. Feebly, she attempted to raise herself up using the pillows behind her. Her voice was weak. Rufus pushed a button to raise the head of the bed up automatically, and as he did so she focused on him weighing whether she could speak a little. She decided she could.

“Where’s daddy,” she said. “He knows I’m here, right?”

“Sure. Everybody knows. They got the bastard. You know, the one who did this.” He pointed at her. “You’re probably going to have to ID him and all that shit, “he paused, adding carefully, “when you’re ready.”

“Oh don’t worry. I’ll never forget that face.”

“A musician,” Rufus added, almost embarrassedly, something a part of her already suspected. She shook her head, then shifted gears, “What are you up to anyway?” It had been a while since they had seen one another.

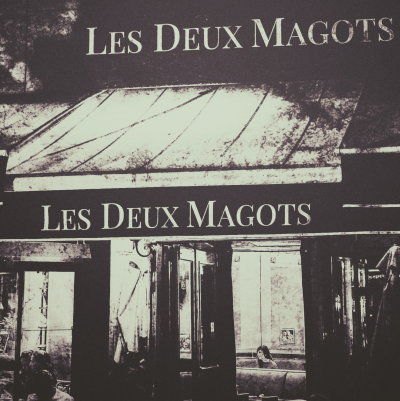

“I’m all right. Le Jazz Hot wrote up my trio. A nice review. I like Paris. It’s a place where people appreciate jazz, understand artists. Here, the only people dig jazz are over 40, dad’s age.”

“I don’t know, Ru. I’m not so sure about that.”

“Look at Redman. Carter. Payton. They’re technically brilliant, but they’re not coming from the music. You know what I mean?”

“Jazz is never going to reach everybody,” she said, but she wasn’t quite sure of where she was going with that, she still felt murky inside, so she switched to the general. “Sounds like you’ve grown, Ru, come into your own.”

“If I have learned anything, it’s that you have to possess more than dexterity and vitality. You have to have control.” He was starting to go off into his own realm, his own analysis of his music, a natural thing, although she was not remotely ready herself to indulge in that sort of thing. She felt a weight in her brain, dragging her back toward sleep.

Rufus leaned over her and kissed her cheek. “It’s OK. I’ll see you soon,” she heard him say as she drifted off.

A day or two later, it was her mother beside her as Chi awakened. Chi had still not seen or heard from her father to whom she was closer than anyone, with whom she had held an unspoken bond she had always felt was unbreakable. She lifted the bandage from the still-stitched wound that ran from the tip of her left eyebrow down to her jawline to appraise the damage in a hand mirror.

“It’s not bad, not too bad,” said Viola peering close at her daughter while clutching her stomach, her eyes darkening. “Oh dear, oh dear, your beautiful face, your beautiful face,” she could not help but say.

“I’m more than a face, mama,” Chi reassured her, although a curlicue of doubt intercepted her considerations. Would she have to prove herself again as a musician on account of this? Could things change that much in an instant? She was not so sure right then.

“I know it’s bad, mama. It’s okay. It’s not going to change the way I play. My skill set is intact. Nobody raped me.”

“Thank you, Lord Jesus.” Her mother buried her face in her daughter’s hands, clasping them hard in her own.

“Lord Jesus didn’t have nothin’ to do with it.”

“Don’t talk that way, honey. We have so much to be grateful for.”

An awkward silence followed, and Viola’s gaze fixed on her daughter’s forehead as if she might find there a sure sign concerning Chi’s future. Chi turned away, eager to shuck aside all the questions and doubt crowding her mind. Beyond the hospital window, a world of realities waited, impossibly far away. Her mother’s worrying, something new, was niggling her too.

“Why hasn’t dad come to see me? Is something wrong? ”

“Oh, he’s fine. Nothing wrong with him at all. He knows you’re going to be fine.”

“Has he been here at all? When I was out?”

“I don’t think so, dear. You know how he is. If he’s not busy with one thing, it’s another. Did I tell you he has a new student?”

“You’re not answering my question, mama. Stop that. Stop covering for him.” The sharpness of her tone surprised even her.

“Honey, I don’t know. You’ll have to ask him yourself. I’m not going to speak for the man. You know sometimes I don’t know how to get through to him. He builds such walls. It’s just how he is, has always been.”

Chi knew there was no logical explanation. Chi knew her father. Why was she even asking? She was his daughter, they were alike. She knew he was ashamed of what had happened to her, ashamed as if it had been her own fault. Carter was viewing what had happened to her as some kind of weakness, just as he saw what had happened to him as having betrayed some weakness in him. “So fucking twisted,” she said aloud although she had only intended to think it.

“Don’t talk that way, Chi. You know I find that word offensive.”

“I apologize, mama. It’s the drugs. They’ll wear off soon. It’s all right.” She patted her mother’s anxious hands not sure herself what the “it” was she was referring to. Perhaps she was just trying to reassure herself. She turned away, shutting herself off, in the style of her father, gazing once more at the window to the outdoors, the beyond, dark as it was now, sunlight departed.

“So it’s going to be like this,” Chi spoke out loud again. She could almost taste the bitterness turning inside her.

This time her mother said nothing, knowing of course what Chi was talking about.

“Why don’t you rest, child. Take advantage of being here and get some rest.” Viola kissed her daughter on the forehead. Even eyes closed, Chi could feel the soft cool breeze of her leaving.

Weeks later, back in her apartment, slowly streaming back into her routine, there was still no word from her father, even on the answering machine, although Chi had heard from practically everybody else — from the musicians she played with to distant cousins and classmates. Once in a while, when her mother called, she spoke for him — “Your father is so relieved.” Once, there was silence on her answering machine. She found herself hoping it had been her father, but of course there was no way to prove it.

She tried to resolve her upset feelings and insecurity by visiting the man, to confront him in some way about his absence and silence. He gazed at her askance when she stepped into the living room and did not get up to greet her. Although that was what he always did, and she knew he was getting old and she herself could use that to excuse him, still, he was going too far at this time, even for him. They had not seen each other in months. Something had happened to her, and he needed to acknowledge it somehow.

“How you doin?” she asked him as usual, as if they had just seen each other yesterday, as if she had just stepped out for milk and in the interim he had arisen for the day. She was that casual.

“Same as ever. And you?” he replied, in his typical way. Yet his eyes, which were pinched, said, “How could you let this happen to you?” Recrimination. Blame.

“I’m okay. Same as ever,” she lied, glaring at him, her eyes narrowing with anger and hurt. Her eyes told him, “Why can’t you forgive me? Forgive yourself?” But like him, she could not bring herself to utter directly what she was feeling.

She stayed for dinner, enjoying her mother’s soul food, hanging with her parents at the dinner table, feeling the silence of their judgment — hers and his — her mother’s being — why are you upsetting your father, why are you challenging him? — as if he was perfect. The unspoken silences between her and her father that she had always held to be so deep, so filled with wisdom, knowledge and love, now just felt cutting, a wound on top of her wound. Seeped in this scenario, she felt herself transformed into a scar and could not shrug off the feeling. Just being next to him, next to his failure to be there, cut deep.

Her mama moved with extra caution bringing dishes to and from the table, her movements, however familiar, also ponderous, weighted. Chi was no longer the same and her parents too had altered, becoming people she hardly recognized, practically overnight.

She told herself she should not have come, should not have expected anything of her old man. It was all too soon, and she of all people should know better. It was evident neither he nor she saw things the way she did. She had experienced something traumatic, life-changing, something that had hurt her in multiple ways. But all he could see was that she had botched some important episode in her life, some performance, and he had expected a higher standard. Well, he had failed too, Chi told herself.

She excused herself, forcing a smile, thanked her mother for the meal, gave her a peck, and her father a chum’s goodbye with a back slap on the shoulder, heading for the door earlier than anticipated, just as George stepped in, peering around it with his know-it-all, wide grin.

“Hey everybody. Hey sis. You lookin’ good.” He grabbed her upper arms, appraising her as one might a potentially valuable object. “You put on a wig and nobody will notice a thing,” he said, looking around for support on this.

“Hey George.” Unable to say more, Chi both acknowledged and waved her brother off while jerking away from his grip. Out of the corner of her eye, she could see her mother’s disapproving glance on George and hear her tsk, tsk.

“You just need to grow up,” Chi told herself fighting off the burn of tears as she strutted away. Her parents were getting old. Good Lord, they had been old when they had her, her mother past 40, and she, Chi, was just being a child about this. She walked for a long time coming finally to what seemed to her an obvious conclusion — the only place to put her discontent and frustration with her family, with what had happened to her was into her music. What was she waiting for?

First few months playing gigs, while her hair was still shorn and she wore a cap over it, nobody said a thing about her scar. It was as if she was a different person. Only after her hair had grown out again, after she had returned to her former image, did people start questioning her, probing openly, forcing her to revisit what had happened to her over and over, until she grew sick of it and of replying. Why did they have to know anyway? What business was it of anybody’s? The only thing that mattered was the music.

Internally, with her music, she was taking huge strides, applying the surprise, hurt and confusion she felt about so much to her practice and performance, going deeper, getting better, persevering and being truer to a self that was both wiser and wilder, a self that was leading the way now. In comparison, her previous life, however successful, felt flat and banal.

Chi switched to a Martin Committee horn, the same type of trumpet Miles had used, and liked the sounds she got from it. She was practicing long hours and playing better at gigs. Then one night at a private party for musicians after Joe Lovano, Dave Liebman and Ravi Coltrane, who were known then as the Saxophone Summit, performed at Dizzy’s Club Coca Cola, Chi got to meet Wayne Shorter. He and Lovano had heard her play before. Both were impressed. Shorter took her aside and said, “I like what you’re doing now, much more experimental.”

“I’m just letting go a little more,” she said by way of explanation.

“Very nice,” he nodded. Wanting to support her, feeling what she was trying to do, Shorter brought her into his group, to let her be wholly who she was musically. Chi took advice from Shorter, something she rarely took from anyone. He even taught her how to meditate, telling her, “it will refine the music and your understanding of it.” He was also the one encouraging her to forgive her parents. “Nobody’s perfect. Invite them to a gig. Carter will enjoy that.” Turns out, Wayne had known her father too back in the day.

Chi had learned from Rufus that Carter had recently been diagnosed with dementia. Her father was no longer the man she had known on any level. Nothing transcendent was going to happen between them. There was no reason not to give them tickets. If anything, it would help her experience some closure, excise the expectations of yesterday. Besides, she was in a good place now, had cut a CD and had written a hit, “Too Damn Bad,” that Wayne had produced. She had a fast growing cult of young musicians and jazz enthusiasts following her too.

Although Chi had given tickets to Rufus for everybody, she had no way of knowing if they’d come to the gig, no way of knowing at all until after the concert, when Rufus peeked his head inside her dressing room door. “Guess who’s here,” he said, making her jaw drop with surprise and joy. There they were, her parents, grinning from ear to ear from the thrill of her performance, just as when she had played for them as a teenager. In a rush of love, she hugged them both. “Wait here,” she said and went to get Shorter, returning moments later, dragging him by the hand into the room so her parents could meet him.

Wayne took Chi’s father’s hand gingerly. “You don’t remember me, do you?”

Carter squinted, as if trying to see rather than place him. Chi could tell he could not remember. Viola brimmed with politeness, speaking for her husband, something she now did more than ever. “It is such a pleasure for us to meet you,” she said.

“Thank you, ma’m.” Wayne took her hand in a gentlemanly style, then turned to Carter. “You’re a hell of a musician, man,” Wayne Shorter said to her father.

“You’re not bad yourself, not bad. But that one,” he pointed at Chi, and she started to blush, the blush prickling the scar on her face that would always be there, making her feel self-conscious and raw.

Her father pointed at her, forefinger quavering with emotion. “I don’t know who that, that woman with the horn is, but I’ll tell you what,” he said adamantly. “She plays better than Miles, better than him.” He looked around himself then, as if for confirmation, knowing he had come upon a vivid realization, something that was true and valid that he could neither deny nor let go, something profound that only now in his demented state, he could dare to utter. Oddly, the eyes of those around him were brimming, although not with sadness, something else he did not quite recognize. “Hire her,” he finished, as if for emphasis.

Love this story. Arya has an obvious love for jazz which comes out in her stories. Great writer!

Love this story. Arya has an obvious love for jazz which comes out in her stories. Great writer!