.

.

Well You Needn’t: My Life as a Jazz Fan

by Joel Lewis

.

.

1.

.

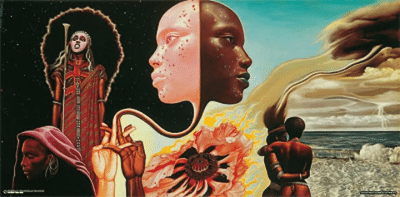

Mati Klarwein’s album art on Bitches Brew, Miles Davis’ 1969 album [Columbia]

.

…..How did one become a jazz fan in the 1970s? As a teenager growing up in Northern New Jersey, jazz was something you associated with the corny sounds that one’s parents and their cronies enjoyed. Jazz was still in the air, but it was mostly associated with World War Two nostalgia and the aging big bands that would still make appearances on the Ed Sullivan show or the Hollywood Palace. I still remember the cringe-inducing TV appearance of Louis Armstrong’s band playing a Beatles melody with all the enthusiasm of deserters facing a firing squad. In my sullen pre-teen years, his hit “Hello, Dolly” was de rigueur at every wedding and bar mitzvah I attended. The message was very clear: rock music was now! as well as being a subversive music that baffled adults.

…..My musical life changed one spring night in 1970. Like most New York City area teenage intellectuals, my favorite radio station was WNEW-FM, a classic “freeform” station, playing cutting-edge rock, with each show reflecting the particular d.j. ‘s taste. Jonathan Schwartz was the thinking girl’s heartthrob, famed for both reading his short stories on the air and his thematic programming that, typically, started a block with “The Rain, The Park and Other Things,” and after three more rain songs, ending with “Here Comes The Sun.”

…..Like many young men of the NYC-area, I developed a crush on “The NightBird” Allison Steele, WNEW’s sultry voiced overnight d.j. Steele began her show with flutes and poetry and always managed to sound like she was addressing you personally, like some sort of auditory hallucination. I was so taken by her that I would call her up during her show and she would talk with me!

…..At some point, she recognized my voice and the sultry tones gave way to the hard-knocks voice of a woman who had been in radio since the late 40s. As to my then ambitions of being a d.j.? “Kid, you gotta watch yourself. There are a lot of assholes out there.”As I grow into my dotage, I realize that the Night Bird’s adage was less a specific approbation than it was a universal truism.

…..Rosko was the station’s only black D.J. He was also the most obtuse in his tone and delivery — he seemed to suggest that he was doing YOU, the listener, a favor just by bothering to show up. He specialized in playing the spiritual grandpas of both Prince, Lenny Kravitz and hip hop , the black rock of the Chambers Brothers, Sly and The Family Stone, Love, and the Godhead himself, Jimi Hendrix. Often, he would stop his show cold to read poetry or to read a long critique of the still-raging Vietnam War, both accompanied by ethnic chants courtesy of a Nonesuch World Explorer LP.

…..“Miles Davis … Spanish Key” growled Rosko one fortuitous evening and out came 16 minutes of unprecedented sound. Instrumental. And with a trumpet as the lead instrument. Unlike the progressive rock I loved, “Spanish Key” did not resolve melodically and appeared to lack an identifiable melody. The listener was forced to accept the performance’s sound world on its own terms. Who was this Miles Davis, anyway? I got my answer the next day at Communications, a hippie-run record cum head shop that only stocked albums that you heard on NEW. (“You want the Carpenters? THE CARPENTERS!! Get the fuck out of my store!” I once recall the hippie-dude proprietor tell some hapless square with a good deal of zeal.).

…..I bought Bitches Brew, which contained “Spanish Key,” with the album, a part of Columbia Record’s price point two-discs-for-the-price-of-one series (“Hey, that platter’s Hip!” Mr. Hippie Dude declared as he tendered back change). At home, I found myself transfixed by the wrap-around artwork by Mati Klarwein, whose LSD-drenched manic landscapes would later drape about Santana’s Abraxas album. What’s going on here, I thought, especially this Davis guy, who was as old as my father and the all lower-case liner notes by Ralph J. Gleason (who I recognized as a Rolling Stone editor), who was writing about this unknown old guy like he was Clapton or Hendrix. Over the weeks, I played Bitches Brew nearly every evening. This is not to say that that I got “it,” but was intrigued enough to investigate further.

…..Over the course of my high school years, I became a full-fledged jazz fan. However, the only people in my peer group who seemed vaguely interested in the music were the drummers under the spell of Buddy Rich. Ah, loud mouthed, talent-wasting Buddy! Tapping out paradiddles on Johnny Carson’s desk with a pencil. Suggesting that the Cream drummer Ginger Baker’s “ass should be stuffed in a rocket and shot into outer space.” The beads. The Nehru jackets. His obsessive hatred of Billy Cobham. These drummer boys loaned me his albums to listen to and each one left me more depressed than the one I listened to before it. Most of it seemed to be about some old guy trying to stay hip (and as an old guy myself, it still is not a good idea) and doing swinging versions of “Jesus Christ, Superstar.”

…..I began listening to WRVR, the radio station of Riverside Church and the only full-time jazz station in New York City. Repeated listenings led to a lifelong passion for John Coltrane. Although Trane has been on a postage stamp, depicted in a Memorex TV ad, and is part of the pantheon of hip hop forefathers, back in the early ‘70s he was unknown outside of the jazz world. My first album was the Impulse disk simply called Coltrane, featuring a bluish, abstract photo of the tenor saxophonist. I would play “Out Of This World” over and over again, much to the consternation of my parents, who thought the sound of Coltrane’s saxophone was worse than any of the squalling rock guitarists I used to play on our crummy Magnavox stereo. I soon began haunting the cutout bins of King Karole’s on 10th Avenue and 42nd Street and began reading whatever jazz books our modest local library contained.

.

2.

.

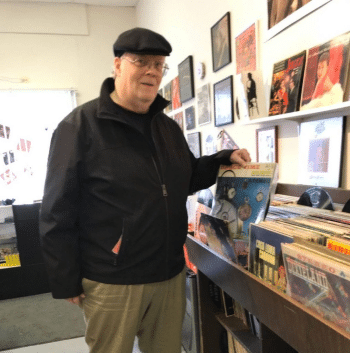

Bob Porter

.

…..Having spent all my money and brain power on collecting jazz albums, I was wholly unprepared financially or grade-wise for college and ended up at William Paterson College. To my amazement, they actually had a jazz program and I signed up for a jazz history class conducted by trumpeter/composer Thad Jones. Thad in ’73 was beloved by both boppers and by big band enthusiasts for the band he co-led with drummer Mel Lewis. And in the racial confusion of the post-Civil Rights era, the band got much play as it was co-led by a black guy from Detroit and a Jewish drummer who paid his dues behind the kit in the ultra-white Stan Kenton Orchestra.

…..Beyond his skills as an arranger and bandleader, Thad was a great composer whose “A Child Is Born” remains a standard today. His arranging and composing skills overshadowed his abilities as a trumpeter, a favorite of Thelonius Monk, Charles Mingus, and Miles, with the latter once declaring “I’d rather hear Thad Jones miss a note than hear Freddie Hubbard make ten!” Pedagogy was not, however, Thad’s strong suit. Maybe I’m harsh in that assessment, as he didn’t show up to teach all that much, with his classes most often covered by Vinson Hill, a no-name pianist pioneer jazz educator who took his teaching seriously. Thad mostly played LPs from his record collection and then made somewhat cryptic non-sequiturs such as: “Does the name Tricky Sam Nanton mean anything to you?” or “When I was a young cat, when we said that someone was funky, it meant that the cat smelled!” However, it was a thrill to be in the presence of a real live jazz musician. And when Thad was awarded an honorary doctorate from Willy Pee, he didn’t give no boring speech. He pulled out a trumpet from under his robes, then played and made it the hippest graduation ceremony in America that year.

…..It was on a sunny spring day that I was walking along Bergenline Avenue late in my freshman year of college when I came across a record shop that seemed to have sprung out of nowhere across from Delancy’s candy shop. The sign across the store window “Everything from Bunk to Monk ” seemed like a blunt message from a higher force. I crossed the street and peered inside. “Holy crap! It’s a jazz record shop!” I went inside and heard the sound of Dizzy Gillespie pouring out of the speakers and the walls covered with LPs by Charlie Ventura, Alan Eager, Sonny Criss, and other great but obscure figures so beloved by the serious fan. The shop owner was Bob Porter, recently canned from his gig at Prestige records when the Bergenfield, NJ label was acquired by Fantasy records on the strength of the millions they made on Creedence Clearwater Revival. Bob, of course, would later gain fame as a host on Newark’s jazz station WBGO as well as his NPR show “Portraits in Blue.” And true to the code of every indie book , comic book, and record shop guy, he was diffident and aloof. His assistant was a young cat from Brooklyn named Eddie who played tenor and was studying with the great blind pianist Lennie Tristano. Over the course of time I hung out at the shop, I caught Eddie walking around the store with his eyes closed, bumping into the bins (“I was just trying to see what Lennie’s world was like”) singing Charlie Parker solos, playing Diana Ross albums (“Lennie says she’s the new Billie Holiday”) and reading the selected writings of Leon Trotsky (“Lennie is into him, so I decided to check him out!”). Poor Eddie also spent most of his paltry pay going into psychoanalysis because Lennie told him, “Eddie, you got to resolve your issues with your father if you want to be a great player.”

…..A few months after my introduction to Jazz, Etc., Bob called me at home. “Hey Joel, Eddie split. You want the gig?” I handed my cashier’s apron back to the Pantry Pride supermarket I was working at and began my career in jazz land on Lincoln’s birthday. In making the transition from customer to flunky, I realized two things: Bob was really politically conservative and he hated the avant-garde jazz that I was enamored with. Although I was in my high radical phase at college – Karl Marx was my toilet reading, attending “Justice for the Rosenbergs” rallies, and being able to spell “bourgeoisie” without recourse to a dictionary- politics were easy enough to sidestep. Albert Ayler was another matter. “Joel, turn that shit off! Man, that guy can’t play!!” He was also equally appalled by Anthony Braxton (“Man, can’t that guy give a song a title?”), Cecil Taylor (“that guy is jiving you”), and Gato Barbieri in his avant-garde phase (“Joel, turn that shit off, man, that guy can’t play and did somebody drive a nail into his foot while he was recording??!!”). Bob’s great love was bop and the soul jazz which then appalled me. He produced most of Prestige’s soul catalog and had a hit with Charles Earland’s version of “More Today Than Yesterday” and tended to play mostly albums he produced. I found much of the music indistinguishable, with most of the organ groups melding into one another.

…..Work, such as it was, consisted of filling and shipping orders through the mail-order catalog that was the heart of Jazz Etc.’s business. The big sellers were the collector’s label that mostly consisted of air checks that audiophile jazz nuts recorded in the fifties when tape recorders were introduced. The king of such enterprises was the mysterious Boris Rose, who was an engineer for the Mutual Broadcast System back in the fifties and thus had access to the best equipment. As issuing air checks without permission was illegal and Rose was somewhat paranoid, his records were rudimentary and they obfuscated details. Terrified that song publishers would arrest him, he changed the song “My Favorite Things” to “Stuff I’m Partial To” and “Embraceable You” to “You So Good To Hug.” He also had a perverse streak, given to issuing, say, a Woody Herman’s “Second Herd Volume Two,” without bothering to put out a Volume One. And to my kid brother’s delight, Boris even issued a bootleg of the legendary farting contest album. Our Big Day was Saturday, when jazz nuts from New York would venture over to hang out and peruse our bins. There was Jerry Valburn, who was in possession of millions of feet of air checks by Duke Ellington, which were eventually purchased by the Smithsonian.

…..Then there were the guys obsessed with Prestige “yellow labels,” that is, Prestige records of a certain vintage when the LP labels were the shade of old Velveeta. No Saturday would be complete without a call from the late Harvey Pekar, remembered fondly for his “American Splendour” comics, but at the time just a pain in the ass from Cleveland. Harvey would always call wanting to discuss Gene Ammons records with his ex-producer Bob. “Tell that nut I’m out of town!” Bob would growl. And, of course, among the myriad bald pates, goatees, and bad postures, rarely did the female form pay us a visit. The only women jazz fans seemed to be the wives of the most severely demented fans and I suppose they became fans just to understand what the fuck their husbands were talking about and wasting their money on. When an attractive woman popped in to buy a disk–even if it was some commercial crap like George Benson or Grover Washington—it was an event we’d discuss for days.

…..Listening to these men, I got a total anecdotal history of jazz. Guys who hung with Bird, found Red Rodney a dentist for his bad teeth, watched Woody Herman pee on the leg of a semi-comatose Serge Chaloff, drove Duke Jordan back from a gig and then watched documentaries on soybean harvesting with him on woeful early am TV. I was the “kid” and that rare kid who liked jazz, as their kids were all rock fans – I was even forgiven for my peculiar taste for free-form sonic blow outs. In retrospect, Archie Shepp howling away was my version of Metallica, an angry music that balmed my unhappy college self dreaming of social revolution and/or a girlfriend.

…..The most memorable of characters was Teddy Reig, the man who produced Charlie Parker for Savoy and whose huge frame kept Bird’s casket from sliding into the rainy streets of Harlem after the funeral at Abyssinian Baptist Church. He was of genuine “Jazz History,” managing Count Basie’s band, going out and scoring junk so his musicians could complete sessions and being on a first name basis with the various gangsters that provided fuel for the jazz life. Teddy would barrel into our store, smelling from the garlicky knoblewurst sausage he had just consumed at Wolf’s Deli across the street, which he’d ritually wash down with Dr. Brown’s Cel-Ray. He was the kind of guy who talked in bellows and if you didn’t seem to be paying attention to him, he’d hit you with the cane that” kept his big frame vertical. “Hey, kid! Howya doin’?” he’d roar at me. Then he sat down at our phone and began calling his gangster pals in Newark. We were sure that one day we’d get arrested because of Teddy. Although Teddy would hold court with various tales of the stars he produced, which usually involved finding so-and-so nodding out in a bathroom stall or falling asleep in the middle of a solo, Teddy also had a weird sentimental side. One day, when I was running an empty store and with no one to perform for, Teddy began telling me of his latest discovery, George Benson’s pianist Jorge Dalto. “I want this album to be a hit,” he told me gravely, “because I want to show my daughter that I’m not a bum.” Sadly, the Dalto album tanked, as Dalto literally did a few years later, dying young of cancer. Teddy did live long enough to gain fame as Charlie Parker’s producer.

…..Jazz Etc. closed in ’77. Bob had started to work for the newly revived Savoy label and decided to pack in the money-losing storefront. I was graduating from college and thought a second about taking it over, but never got past that ghostly thought. Other things were percolating in my head: revolution, work and getting out of my parent’s basement. The possibility of becoming a Bernard Malamud-type shopkeeper didn’t enter into the equation.

.

3.

.

Joel Lewis in his basement lair, c. 1976

.

…..After college, I made a stab at professionalizing myself by attending the New School’s Urban Planning grad school. I had made friends at college with the social anarchist Murray Bookchin, whose little book on Urbanism Limits of the City had a big impact on me. I was going to be a humanist Lewis Mumford type Urban Planner who’d create a livable City! — or something like that.

…..Unfortunately, a diagnosis of Type 2 Diabetes derailed that particular train. Not that I was hospitalized or heavily medicated, I just sunk into a realm between Dysthymia and Full-On Depression. I withdrew from classes and hung around my parent’s house listening to, what else, jazz LPs.

…..The one thing that I managed to do was to start writing poetry in a far more serious manner than I did in college. Back there, I was all into the Beats, especially Jack Kerouac, whose On The Road was the Gateway drug into jazz for many. Allen Ginsberg’s fifties-era poetry was laden with references to jazz and jazz musicians and put the phrase “Bop Kabbalah” into the American language estuary. When Howl was published, he trudged over to the Five Spot club and gave a copy to his idol Thelonious Monk. In a later encounter with the “High Priest of Bop”, he asked the pianist what he made of the book. “Makes sense!”, responded Monk.

…..My early attempts at poetry were more the product of killing time waiting for a bus — the damned fate of a commuting student without a car (perhaps an intimation of my calling as the late William Matthew’s told me that the only adult males he knew without Driver’s Licenses were poets). The popular poetry models of the mid-70s were Robert Lowell and Gary Synder. The former was a Brahmin goyish poet and the latter was a Zen goyish poet, though winning points for his deep Beat connections and being the model for Japheth Ryder in Kerouac’s Dharma Bums, a popular book among campus literati. Synder’s Pulitzer Prize winning Turtle Island was in high rotation as was his prose book back-pack buddy, Earth House-Hold. However, what did I know of the atmosphere of Lowell’s world of club room armchairs in Beacon Hill or Snyder’s ecotopian vision, especially in a state where Superfund sites double as state parks? And did either of these poets ever write poems about going to the White Castle like I often did?

…..Maybe it’s that depression is undervalued as an engine for creativity. All the rumination and self-involvement can lead to something. I found myself having writing sessions, not unlike a jazz musicians woodshedding pounding away on my Precambrian-era Selectric typewriter, typing up drafts dutifully named Draft #1, Draft #2 and so forth. More importantly I began seeking out other writers, hunting used book shops for poetry and began organizing local reading, an instance where my training in left politics came in handy.

…..Listening to jazz, particularly jazz LPs, prepared me for my introduction into the arts. My copy of Ornette Coleman’s landmark Free Jazz featured a reproduction Of Jackson Pollock’s painting White Heat. I understood that Atlantic Records wanted you to connect the audacity of this “action” painting with Coleman’s radical challenge to chordal improvisation. Likewise, I received an introduction to art photography through the covers of the Munich-based ECM Records. Owner/Producer Manfred Eicher featured some of Europe’s best photographers, using images that hinted at what was awaiting the listeners. Rarely did the albums feature images of the musicians and they never used images of female models, a common art director’s trope. I learned about modern graphic design through Reid Miles cover designs for Blue Note records, LP covers so iconic that they are often referenced or parodied by contemporary designers.

…..My initiation into the Sullen Art introduced me to the many contemporary poets who were jazz fans. Like many fans of the period, the first book about jazz that I read about jazz was Amiri Baraka’s Blues People: Negro Music in White America (written as Le Roi Jones). One of the first books about jazz to be written by a black critic, Blues People and Black Music looked at the social and cultural circumstances of the music. They were also one of the first books to look at the impact of John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman— others books I later read ended their studies with hard bop. I later got to know Amiri and our discussions centered around jazz and not the landmine landscapes of Maoism and Israel. I even interviewed Amiri about John Coltrane for my low rent Mimeo magazine AHNOI!, wherein he noted that John Coltrane was a fan of Blues People. What I learned from Amiri’s poetry was how he incorporated the rhythm and pulse of jazz into his sense of that great boogie bear of open form poetry “the line”.

…..Clark Coolidge, a prolific and highly original language centered poet not only was immersed in jazz but was a jazz drummer active in his native Providence and maintained a rehearsal practice throughout his life. We exchanged contact info after his reading at the Poetry Project and began a lively correspondence mostly about jazz (Clark’s side of the correspondence can be found in Yale’s Beinecke Library). At some point, being young and lacking basic social coding, I invited myself up to Clark’s home up a mountain in the Berkshires. We stayed up late listening to Bud Powell albums. Clark’s tastes in jazz were expensive ranging from early Dave Brubeck Quartets to Cecil Taylor. As my experience as a jazz listener was a solitary project — my friends either had little interest in the music or were openly hostile — it was a pleasure to be able to talk both jazz and poetry.

.

4.

.

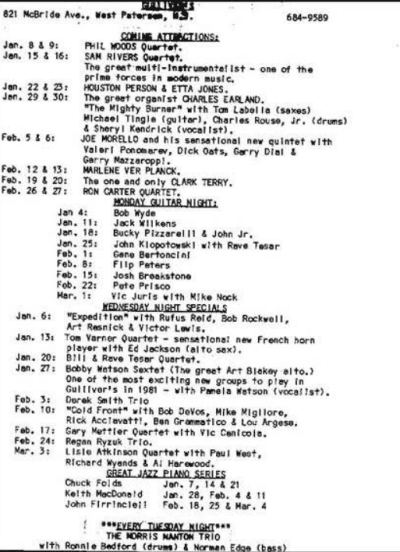

The schedule card on the table of Gulliver’s, a jazz club in Wayne, New Jersey; c. mid-1970s

.

…..Meanwhile, my knowledge of jazz made me employable in the “big box” record stores of the period. I worked at the Sam Goody’s at the Garden State Plaza in Paramus, NJ. Goody’s was a regional chain that offered customers a deep selection of music, including a comprehensive jazz section. What was supposed to be a Christmas season gig was extended when the Teddy Reig wandered into the store. When I told him that when Santa was on his way and I’d be soon hitting the streets in search of a new gig, Teddy went to the store manager and bellowed and banged his wooden walking cudgel insisting that I be kept on— which the frightened Marty Zaro did.

…..When I wasn’t gabbing with my fellow music-obsessed co-workers or handing out “courtesy” discount cards to attractive female customers, much in the manner of a fisherman putting a night crawler on his hook, I was tending the jazz section. I remember meeting singer Phoebe Snow and guitarist Al DiMeola, both of whom were searching for “what the kids are into”. Local players would wander and shoot the breeze and occasionally buy an album. I was a good up-seller of jazz, as I had listened to a lot of the music sealed in the bins and sounded convincing regarding the music’s quality.

…..At some point I noticed that many of the jazz albums lacked personal info on the jacket — it was the era of the gatefold album and you had to buy the album, take off the cellophane to get at the liner notes and who-played drums. Goody’s had a system where albums in the bins were put in a plastic inventory sleeve that gave the album’s name, the record label and the catalog number. When the album was purchased, the cashier took off the sleeve and put it in a box for the clerks who would replenish the inventory. In my role as overseer of the jazz aisle, I took it upon myself to begin writing short capsule descriptions of the albums, including a personal listing. They proved so popular with customers that when I returned for a visit to Goody’s a couple of years after moving on, I saw that my preview labels were still there, but written by someone else’s hand— when the inventory sleeves wore out, someone recopied my little reviews.

…..I did not go out to the Manhattan jazz clubs a whole lot in my bachelor days given the deleterious effect it had on my dating life. I took Doreen, a striking looking woman who I knew from college, to see Cecil Taylor at the long gone Fat Tuesday‘s near Union Square on a cold night in early February 1980. Cecil had two drummers and played an intense set of a continuous performance that was recorded by the Swiss Hat Hut label and issued as It is in the Brewing, Luminous. At the set’s conclusion, the audience exploded in applause and shouts, except for one person. “That didn’t sound much like Fleetwood Mac,” Doreen mumbled and that was the last time I saw her, no doubt leery of any further adventures in the atonal wilderness. It reminded me of my friend Ed’s reaction when I took him to see Anthony Braxton at the resurrected Five Spot. Ed, who bonded with me around a mutual love of the Beats, hated what he was hearing; but what I think disturbed him more was that everyone around him loved what they were hearing,

…..I did love going to the long vanished jazz clubs that existed in the suburbs of North Jersey. Near William Paterson, were two jazz clubs. Both were within walking distance of each on McBride Ave, hard alongside the Passaic River. The Three Sisters featured members of the Thad Jones-Mel Lewis orchestra and with Thad and Mel often playing in a quartet. Phil Woods often played there, as well. The atmosphere was a bit clubby and the groups seem to be playing for the group’s amusement, rather than for the audience – something my rock-oriented friends picked up on when I cajoled them into joining me for a set. Did Mel Lewis really have to take a drum solo on a slow ballad?

…..Further down the road was Gulliver’s, run by Amos Kaune, who had managed clubs in North Jersey for years. Amos’s club was hipper and brought in more contemporary players. I remember seeing tenor saxophonist Joe Farrell and trombonist Bill Watrous- hot players in the mid 70s. There was nothing fancy about the club and the cover charge was five bucks plus a drink minimum. You could stay all night as long as you bought a drink for each set. The audience was a mix of older fans—the Paterson area was once a hot scene that produced singer Joe Mooney, guitarist Bucky Pizzarelli and pianist Al Haig— and young musicians who were studying with the many jazz musicians who lived in the area, along with the occasional civilian like me.

…..My great passion in those days was for the fringes of the jazz scene – it went by many names: “Out Jazz,” “Experimental Jazz,” and “Free Jazz” were some of the terms that its devotees used. “Turn that shit off!” was a conceptual term used by that music’s detractors. None of the Midtown Manhattan clubs featured the music and Cecil Taylor was the only advanced performer who regularly played clubs like the Village Vanguard – his devoted following always assured a packed house. A lot of the performances took place at galleries, art spaces or other one-shot spaces. There was a great series at the Public Theater that featured many performers in tenor saxophonist David Murray’s circle.

…..One of my favorite spots was a loft on far West 52nd Street was Verna Gillis’s Soundscape. I used to walk from the Port Authority for the 12 block walk along deserted 9th Avenue assuming I would get mugged before I got to hear some music. Once I arrived at 549 W52nd, the “Midnight Cowboy” atmosphere shifted to one of music and art. The space was filled with the sculptures of Bradford Graves that doubled as musical instruments. The audience was convivial and the admission was well within my limited budget (& no drink minimums). It was even more intimate than a Jersey club, you sat on a folding chair and could sit directly opposite the performers if you desired. It not only featured local players like guitarist Sonny Sharrock, but she brought in players from Europe. It was thrilling to hear the expat soprano saxophonist Steve Lacy, whose LPs took up a serious chunk of my shelf space; but I was bewildered to hear him with a pianist in his band and playing more conventional type material. I went up to him after a set (there was no dressing room for musicians to retreat to) and asked him about his shift in music. “Joel, I’ve played the music you’ve been hearing on my LPs for over twenty five years. I thought it was about time to try something new.” It was a good lesson in active aesthetics for an apprentice poet.

,

5.

.

The cover of Al Kooper’s 1994 album Rekooperation (Music Masters)

.

…..Well, what does one do with a brain-pan overflowing with the effluvia of years of reading liner notes, Jazz histories, downbeat and Rolling Stone magazines, record store aisles bull sessions & in-between set conversations with the makers of the music? I began writing about it.

…..I must admit to having a timeshare in the Imposter Syndrome co-op. I can’t play an instrument, never took a music lesson and have a faint knowledge about the chassis that runs the music machine. Realizing this gap in my cultural kitbag, I took a Music Appreciation class at William Paterson. The teacher was a nice guy, he went to DePaul University with the band Chicago’s horn section and would play sections of soundtracks for the porn films he scored to supplement his adjunct’s salary. Maybe it ties in with my Battle Royal with mathematics, but the basics of music was a torture rack. The teacher took rachmones (compassion) on me and gave me a mercy “C” in exchange for a Singers Unlimited LP that I special ordered at Jazz Etc.

…..By focusing on placement of music in its cultural, social and historical setting was my go around. I began in college by interviewing Bucky Pizzarelli, who taught at my college, and using my connections with Bob Porter to interview guitarist Pat Martino, a hero of mine. I sat through hours of a rehearsal for an important gig that was not going well and it was a lesson for me in how music gets put together. Afterwards, Martino sat down with a twenty year college journalist and was patient and open. I suppose he was also surprised that I was conversant with his entire musical career.

…..After college, I wrote a lot for the Jewish presses, especially the newly launched English language version of the venerable Yiddish paper The Forward. As long as there was a Jewish angle, I could pitch a story. I interviewed rock music’s Zelig, Al Kooper. Kooper’s career ranged from playing organ on Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone” to discovering then producing the southern rock band Lynyrd Skynyrd — not to mention founding and then quitting the horn- based Blood, Sweat and Tears.

…..Kooper had just released his first album in years, having been semi-retired for a while thanks to songwriting credits that included “This Diamond Ring” made famous by Gary Lewis and the Playboys and in constant play on radio since its 1965 release. Kooper’s cranky persona reminded me of some of my uncles, except that he formed the legendary band the Blues Project instead of an accounting firm. He also gave me that Jewish sweet spot that sell the story to editor: “Mike Bloomfield told me that the reasons that Jews are attracted to the Blues is that Jews suffer internally and Blues is all about external suffering.” Before we concluded the interview, I revealed to Kooper that when I went to Jewish day school, we sang the daily prayer “Yigdal ” to the melody of “This Diamond Ring.” Our deeply Orthodox teachers were befuddled by the strange melody and my friend Moishey’s explanation of “it’s a Sephardic melody I learned when I was in Israel ” sounded reasonable. They were also, no doubt, impressed by the energy we put into that old Hebraic warhorse. “Hey man, sing it for me,” Kooper exclaimed. And I did, almost on command. “Hey, man,” he responded, “that sounds cool. I shuddah paid more attention to my rebbes!”

…..I do take some credit in helping promote the new wave of Klezmer music that was brewing in the cities of the North East. My editor, Jonathan Rosen, gave me the stink-eye with my initial pitch but the newly emergent scene was hard to ignore within the Jewish cultural community. In particular, I wrote a number of pieces about the Klezmatics, who brought a “downtown” aesthetic to the music, which included being queer-friendly and with cheeky albums titles like “Jews With Horns” and “Rhythm and Jews.” I was in attendance at Radio City Music Hall for a sold-out concert featuring Yitzhak Pearlman and the crème de la schav of the Klezmer scene. I even brought my parents along to the event. At the reception after the concert, I introduced my folks to the musicians who performed that evening. My father, an Auschwitz survivor who was unenthused by this music of the shtetl culture he grew up in, got impatient and exclaimed: “Nu, when is Pearlman coming out?” I had to explain that the great violinist post-concert repast did not include cheese cubes and vegetable sticks.

.

6.

.

Ornette Coleman and Joel Lewis at the New Jersey Performing Arts Center; 2006

.

…..In the days before internet culture, you call up an editor on the phone and pitch a story. Which was what I did when I heard that Moondog, a blind street musician dressed in robes and topped with a Viking helmet, was coming to play a concert at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Moondog had been a New York City personality in the 50s & 60s, reciting his poetry and playing his self-invented percussion instruments and then disappeared off his corner at some point in the early 70s. Although Bob Porter assured me that Moondog was dead and I was going to meet “some fake Moondog.” When I got to the hotel on lower Lexington Avenue, I was confronted with the genuine Moondog, sans robes and helmet. He told me that he went to Europe to perform some concerts and stayed on. It was his manager who convinced him to update his wardrobe, so as to be taken more seriously as a composer. Which the European audiences did and the last decades of his life were filled with performances. Years later, I gave a reading of my Moondog profile in a Reykjavik record store called 12 Tonar. Icelanders, many of whom are descendants of the individuals named in the Norse sagas, love Moondog. Apparently, chess players as well. As I was leaving the record shop, the store owner, Johannes, told me: “Do you know who was watching you read? Bobby Fisher!” Fisher had found refuge in Iceland when no other country would take him in; the proviso was that the chess genius would refrain from the crazy, Anti-Semitic and just plain Anti-Whaddaya- Got rantings that made him a meshuggah non grata wanted by the U.S. government. Johannes added that he often saw Fisher wandering the streets of the city and, no, he didn’t think Fisher was a Moondog fan.

…..My longest sustained period writing about music came when an old student of my wife became part of the publicity staff of the New Jersey Performing Arts Center(NJPAC) in Newark. NJPAC was part of an ambitious project that brought a minor league stadium, luxury housing, a light rail extension and a performing arts center to downtown Newark. After a bad experience with hosting a Hip-Hop concert in the inaugural seasons, management began focusing on musical forms whose fans would treat the facility more gently — which brought in a stream of jazz performers to the main stage.

…..Most of my interviews were “phoners”. I would talk to a publicist, who would give me the performer’s phone numbers and a time to call. I would do an interview with eyes on “pull quotes” as part of my profile. The musicians I was talking to had moved up from club work to the concert hall and were familiar with this part of the publicity process. Most were surprised to be interviewed by a real live jazz nut, rather than someone who gleaned his/her’s info from a Wikipedia entry.

…..These interviews also opened up my jazz world view, which favored the extreme edges. My early jazz mentors were the worst form of Black Nationalists — white Black Nationalists who viewed anything melodic and/or a chord sequence with deep loathing. So, there I was, interviewing Dave Brubeck, a particular object of scorn of my sunglasses-at-night mentors. But Brubeck was great to talk to and was even aware of the sqrounk-music tribute to his compositions that John Zorn produced for a Japanese label. “Man, they were really far-out versions of my tunes,” he said with a laugh. Apparently, Dave dug our interview and requested that Columbia records hire me to do the liner notes for an Essential Dave Brubeck compilation for more money than I ever got paid for writing about music.

…..When I was interviewing Ramsey Lewis, who had a string of top ten jazz hits during the Beatles early heyday and remained a popular concert attraction, whether he ever got tired playing his very popular version of Dobie Gray’s “The In Crowd,” he responded: “There may be someone coming to one of my concerts for the first time and has been listening to my music since he’s been a youngster. How could I not play the ‘The In Crowd’ for him?”

…..When the call came to interview my hero Ornette Coleman, I decided that I had to meet him in person. My editor wrangled a contact number to Ornette’s cousin and manager, James Jordan. I contacted Jordan, who was hesitant to allow an in-person interview. I unloaded a cartload of reasons, made-up as I went along and Jordan then said he’d passed my request to Ornette’s son, Denardo, who as both a drummer and producer worked closely with his dad since he was a pre-teen.

…..My day job at the time was as a social worker at a truancy reduction center. We attempted to curtail truancy by having the cops pick-up those young daylight loiterers and put them in our center until their usually furious parents came to redeem them and return them to school. My day was done and I was waiting for a bus when Denardo called. I told him that I knew his mother, Jayne Cortez, as we were both published by Hanging Loose Press. I then launched my “Hail Mary” pass, mentioning that the interview needed to be done in the late afternoon because of my social work gig. “My wife is a social worker, too!” said Denardo. TOUCHDOWN, and we set up a time to meet his father.

…..Ornette’s loft was located in the Garment District, a short walk from the Port Authority bus terminal. James Jordan greeted me when the elevator arrived at Ornette’s floor. The space was airy and well lit and filled with art. When Ornette came in and introduced himself, I had to push teenaged Joel back down inside and perform as adult Joel. Ornette was dressed in an amazing multi-colored silk outfit, more appropriate for the royal court of Sun Ra’s home planet Saturn than the urban charivari of West 40th Street. I later read that all of Ornette’s clothes were bespoke and he wore a new outfit every day.

…..Interviewing Ornette was a tougher task than I imagined. He talked obliquely and it was hard to get straight answers to softball questions. As for his near decade absence from performing and recording he revealed no more that he was traveling and “listening to new things.” However, when I asked him what album new listeners should get as an introduction to his music, he quickly said: Skies of America – the 1972 album featuring the London Symphony Orchestra, with Ornette improvising over a notated score. It was an album that divided his fanbase, stood in contrast to the open style of his many records and whose high production costs was probably the reason that Ornette was dropped from Columbia records. In my home alcove workspace, next to my photos of Ted Berrigan and Charles Olson is a photo of Ornette and myself backstage at NJPAC taken by my wife. What would teenage Joel make of that?

.

7.

.

Joel Lewis, 2023

.

…..I’m not going to say that jazz is my religion, as Ted Joans did, as I think too much of it to put a church about it. I wish I had learned an instrument, even a melodica, but my formal laziness scared me away from the scales and practice that go with it.

I don’t hear as much as I used to about “Is jazz dead?” It has a presence in the culture that it didn’t have when I was a kid. More sophisticated pop-music fans know who Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Thelonious Monk and Bill Evans are. The expansion of jazz programs around the country guarantees not only a flow of well-educated jazz musicians but jobs for older jazz musicians who will teach them. Jazz is an international music now, with many regions producing talented performers who often train at U.S. schools or at the many jazz programs that exist around the world. When I attended the Copenhagen Jazz Festival a few years back, I was struck that not only were there no American performers, but that most of the acts came from northern Europe. I finally understood Phil Woods’ complaint when I interviewed him for an NJPAC profile that “Work is drying up for me in Europe!” Instead of imitating their American heroes, European musicians have developed their own musical vocabulary and a cadre of innovative performers.

…..Part of my history closed when Bob Porter died in April, 2021. I was pleased by the extensive obit in the New York Times and that he had become such a well-known figure in the musical world, that his passing was covered on many media platforms. I used to hear from Bob from time to time, usually when I needed a quote for an article or information to track down a source. And once, on my way to New Orleans with my wife for one of her film conferences, I looked across the aisle and there was Bob! Diffident as always, he said HI! as if we just saw each other last week instead of 15 years before. After a couple of minutes of pleasantries, he looked at me and said, grimly: “Hey, Joel, are you still listening to that god damned avant-garde squawking?”

.

.

___

.

.

Joel Lewis is a New Jersey-based poet and writer as well as a recently retired social worker. He is the author of six books of poems. His forthcoming book for Hanging Loose Press (Spring ’24) will include this jazz memoir.

.

.

___

.

.

Click here to read previous editions of “True Jazz Stories”

Click here to read The Sunday Poem

Click here for information about how to submit your poetry, short fiction, or True Jazz Story

Click here to subscribe to the (free) Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter

Click here to help support the ongoing publication of Jerry Jazz Musician, and to keep it commercial-free (thank you!)

.

___

.

Jerry Jazz Musician…human produced (and AI-free) since 1999

.

.

.

Cool story. Billy Cobham is the second coming of Christ on drums.