The publication of Arya Jenkins’ “The Piano Whisperer” is the 14th in a series of short stories she has been commissioned to write for Jerry Jazz Musician. For information about her series, please see our September 12, 2013 “Letter From the Publisher.” Also…following the conclusion of this story is news concerning this collection of stories.

For Ms. Jenkins’ introduction to her work, read “Coming to Jazz.”

*

The Piano Whisperer

by

Arya Jenkins

In the underground of how it used to be, in days long ago when things were quite good, when the only bad thing, if you want to call it bad, was poverty, which was longstanding, a dull ache of years that traveled with you through good times and bad and sometimes sang you to sleep like a sad horn, bwa la la la (high note) bwa la la la (high note) bwa la la, in that time, the song of poverty that belonged to everyone belonged also to Noname.

Noname, pronounced Noh-nameh, ran bleak streets then 60 years ago when the world was kinder, a better place, where murder was just, well, murder, and horror, ordinary, conceivable, and every person, regardless of how they appeared, who they were, part of a diverse evolving unique American gyroscopic system. Even the most jaded soul understood being different was natural, even if your difference was made of so many facets, no one thing stood alone and nothing alone could capture it — save poverty herself, true interpreter of shades and depths of differences, which we celebrated on saxophone streets, in piano bars and when looking to the heavens for inspiration in the form of star notes seeping through the black ceiling of the sky.

We walked to the pier and back, crossed the river many times, snuck onto boats. Late nights when high on dope, danced invisibly across wires that sang between buildings foreshadowing a future of untold messy connections in electrified space, wandered from place to place the way music wanders and language, taking each thing we touched, each experience into the next, creating musical compositions out of that which could not be assimilated any other way.

It was the artist in the child of Noname wanting to connect things, a pure desire that arose out of her authentic lineage and testified to her true belonging in that unseen space and time, where artistry is conceived and these days must hide.

Her roots were royal, her father’s books, little comprehended, featured on bookshelves in stores throughout the country, her mother’s music played in every record store. Her mother’s profile, defiant chin arching upward decorated the side of a brick building in Soho — a club was named after her in the West Village and one in Chicago.

At dawn, after a long night listening to everything there was to hear and seeing what there was to see, we sat on a bench watching time on the Hudson River. I watched Noname imitating me as she mused, trying to anticipate her direction. Noname sat there calm, proud head crowned with dredlocks the color of soil, her well-defined nose and blue eyes slit, behind them, an acknowledgment of, well, darkness, the state of things, aimed across the river as if reality, truth, what mattered, was more apparent there.

“I want to fuse things, make something new,” she said. I nodded, and told her she could do whatever she set her mind to. “That’s my girl,” I said, plain as day, just as its first fingers stretched toward us across the river.

Noname’s hands were long, tapered at the ends like her mother’s and like her mother, she was skilled, even effortless, on the piano. She had learned a few lessons from me, hanging around all the bars where good music played, but her understanding was inherent, her mother’s gift.

She was versatile on the instrument, covering all jazz and blues standards without a blink and skilled on drums too, although that was a secondary thing, an accompaniment and rest in her mind. It was her idea I conduct drums in her mind. We heard drums whenever we traipsed along the avenues and side streets of New York, Pittsburgh, Chicago, or Kansas City hanging out on stoops, outside cafes or clubs. ‘Twas drums we heard, whenever we ran from some bloody scene or riot. Whenever it rained or snowed, drums grew soft, almost tender, a third heart beating between us to time and its exigencies. But it was piano Noname played as she evolved as a musician despite her parents’ lack of presence.

Truth was, her parents had not had a clue what to do with her. They themselves had been together just a minute, long enough to create her, celebrate her explosion in their consciousness, ecstasy that came between them. She came into the world and were off doing their own thing, one signing books, talking the world to death, the other playing music, giving a new face to pride. The girl, Noname, was on her own. “You’re a happy consequence,” I told her when explaining her state of orphanhood.

Thankfully, the streets, which are the best teacher, helped me raise her. By the time she was a teenager, we were masters of happenchance. One day, passing a store, we peered in the window together at a sea of pianos—black, brown, white, creamy and golden. “Look at that.”

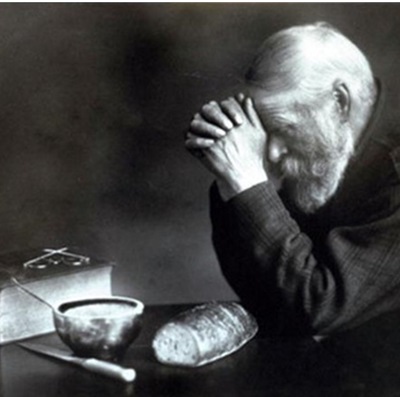

We went in. The balding manager sat at a desk in back, busy over paperwork, looked up, nodded, waved, like “do what you can to fill this stodgy room with something beautiful.” So Noname picked a black upright, settled upon the bench before it, hesitated a prayerful moment before placing her hands on the keys, black and white, loving each distinctly, with equanimity, and played one of the first blues’ riffs I’d ever taught her by Muddy Waters.

That was our lunch date that day, bread and butter, soul connecting to the future’s pregnant abundance. Noname played the future, sitting at a piano, mastering a tune, bringing it forward with her own influence so it had something new — something it had been and something more.

Noname could play just about anything and do justice to a tune whether she was on an abandoned instrument left to rot on the streets, a forlorn one in some remote corner of a library, or a beat up one in some funky club. Long as the keys were there, even when not perfectly tuned, she could befriend the piano and use it to tell stories. Her touch had magic, brought people together to listen and left them with a story to think about and connect to their own lives — which is what art is about isn’t it?

Noname played to what she knew, differences and anathemas — ana-what?—and turned around hostilities because the music was love. Her music spoke to resistance and fire, to her ancestry and her will to stay as she was—different–and to create a musical monument out of the host of differences in her.

What does a woman do alone in the world? Her mother Nina asked this of her often, asked it of the mirror while Noname watched, admiring, trying to learn. Her father Andre had no questions, only hard, unyielding certitude. A statement onto himself, he was big-headed and pig-headed, sure as only men can be who have everything from the beginning — name, height, intelligence, acknowledgement, place and therefore the right to do anything, the right to be. But her father hated war, understood art as protest, wanted to fuse art and culture, and surely music. Did he understand music was the key? Did he understand music united everything?

The only thing her father did not understand was where women belonged, what their roles could be, and so he fit them into boxes. He fit her mother and her music into boxes. Can you imagine, fitted his own child into a box, assuming, name would be her only tether to any sense of belonging in the world.

Each child forges her own place, understands legacy and takes from it what she will. An image and word can marry, each out of nowhere conceive something fresh together. But there were ideas that stood apart, that belonged to vast space, emptiness, where connections happen at such a rate they are inconceivable to ordinary seeing and understanding. Still as an intuitive, her mother’s child, she knew where music and time reside, so does the absolute.

Therefore, Noname could not dig ordinary, relative concepts about art, music, life. Life was blues and jazz and had to be infused with these in order to be true. The horns had to protest harder, had to articulate pain and reality with the certainty of a pregnant woman knowing she must give birth.

Noname felt unassimilable, that her differences were alternately convex and concave, and attempted to resolve deep questions about this state that she believed to be that of all things, playing music. Ping, pong, reng, dang, om, pang, reng. The convex became concave. Then she tapped in reverse—reng, pang, om, dang, reng, pong, ping–became convex, saw herself stepping through doors where masters walked escorted, shrouded in finery, and were applauded on stages around the world. She understood that to be one thing you had to be the other as she tendered notes drawing them high, pulling them low, awakening memory, fingers singing, waking onto truth and poverty, the reality of what it means to live alone on city streets even as the world commands you to do other things and pay homage to mundanity.

Pom pam pom pam pom. Pom pam pom pam pom went her mother’s bare feet climbing stairs to her room toward the crib in which she lay naked surrounded only by breeze that blew over her the scent of metal, sky, trees, trucks and debris, scent that demanded music transform it into something beautiful. A curtain puffed derided by wind, brushed her cheek and she billowed.

Whatcha want baby? Whatcha want. Ain’t got nothin’ for ya, nothin’. Just listen. You like this record, huh? You like my voice?

Yeah, she loved her mother’s voice that stemmed from its own history of incongruencies, the gutter, rage, potent streams and citadels, where women’s stories lay scattered, broken, incomplete.

Sometimes her father came up too and tried to sing to Noname, blowing smoke from his cigar toward the window, rocking her with one hand, gazing at her in the box of the crib, wondering into what boxes she would grow.

Daddy, she said in her mind, even as a toddler, gazing at his distracted smile. He heard her voice, her need to reach him and looked down. Listen, she said. Listen. He went away puffing, smiling.

She had to listen for him, for all men, brothers, poets, writers, artists, musicians, who did not make room for women, who did not understand the perfect juxtaposition their intention makes on all art, their intention to make peace, create even in havoc, out of havoc, for havoc.

At dawn, after a long night listening to everything there was to hear and seeing what there was to see, we sat on a bench watching time on the Missouri River. I watched Noname imitating me as she mused, trying to anticipate her direction. Noname sat there calm, proud, a pixie blonde like the actress Jean Seberg, cigarette dangling, pug nose, wide eyes behind which was an acknowledgment of, well, darkness, the state of things, aimed across the river as if reality, truth, what mattered, was more apparent there.

“I want to fuse things, make something new,” she said. I nodded, and told her she could do whatever she set her mind to. “That’s my girl,” I said, plain as day, just as its first fingers stretched toward us across the river.

Noname felt unassimilable, that her differences were alternately convex and concave, and attempted to resolve deep questions about this state that she believed to be the state of all things, playing music. Ping, pong, reng, dang, om, pang, reng. The convex became concave. Then she tapped in reverse—reng, pang, om, dang, reng, pong, ping–became convex, saw herself stepping through doors where masters walked escorted, shrouded in finery, and were applauded on stages around the world. She understood that to be one thing you had to be the other as she tendered notes drawing them high, pulling them low, awakening memory, fingers singing, waking onto truth and poverty, the reality of what it means to live alone on city streets even as the world commands you to do other things and pay homage to mundanity.

Pom pam pom pam pom. Pom pam pom pam pom went her mother’s bare feet climbing stairs to her room toward the crib in which she lay naked surrounded only by breeze that blew over her the scent of metal, sky, trees, trucks and debris, scent that demanded music transform it into something beautiful. A curtain puffed derided by wind, brushed her cheek and she billowed.

Whatcha want baby? Whatcha want. Ain’t got nothin’ for ya, nothin’. Just listen. You like this record, huh? You like my voice?

Yeah, she loved her mother’s voice that stemmed from its own history of incongruencies, the gutter, rage, potent streams and citadels, where women’s stories lay scattered, broken, incomplete.

Sometimes her father came up too and tried to sing to Noname, blowing smoke from his cigar toward the window, rocking her with one hand, gazing at her in the box of the crib, wondering into what boxes she would grow.

Daddy, she said in her mind, even as a toddler, gazing at his distracted smile. He heard her voice, her need to reach him and looked down. Listen, she said. Listen. He went away puffing, smiling.

She had to listen for him, for all men, brothers, poets, writers, artists, musicians, who did not make room for women, who did not understand the perfect juxtaposition their intention makes on all art, their intention to make peace, create even in havoc, out of havoc, for havoc.

At dawn, after a long night listening to everything there was to hear and seeing what there was to see, we sat on a bench watching time on the Chicago River. I watched Noname imitating me as she mused, trying to anticipate her direction. Noname sat there calm, proud, bald and bold, flared nose, sensual lips, hazel eyes behind which was an acknowledgment of, well, darkness, the state of things, aimed across the river as if reality, truth, what mattered, was more apparent there.

“I want to fuse things, make something new,” she said. I nodded, and told her she could do whatever she set her mind to. “That’s my girl,” I said, plain as day, just as its first fingers stretched toward us across the river.

Noname felt unassimilable, that her differences were alternately convex and concave, and attempted to resolve deep questions about this state that she believed to be the state of all things, playing music. Ping, pong, reng, dang, om, pang, reng. The convex became concave. Then she tapped in reverse—reng, pang, om, dang, reng, pong, ping–became convex, saw herself stepping through doors where masters walked escorted, shrouded in finery, and were applauded on stages around the world. She understood that to be one thing you had to be the other as she tendered notes drawing them high, pulling them low, awakening memory, fingers singing, waking onto truth and poverty, the reality of what it means to live alone on city streets even as the world commands you to do other things and pay homage to mundanity.

Pom pam pom pam pom. Pom pam pom pam pom went her mother’s bare feet climbing stairs to her room toward the crib in which she lay naked surrounded only by breeze that blew over her the scent of metal, sky, trees, trucks and debris, scent that demanded music transform it into something beautiful. A curtain puffed derided by wind, brushed her cheek and she billowed.

Whatcha want baby? Whatcha want. Ain’t got nothin’ for ya, nothin’. Just listen. You like this record, huh? You like my voice?

Yeah, she loved her mother’s voice that stemmed from its own history of incongruencies, the gutter, rage, potent streams and citadels, where women’s stories lay scattered, broken, incomplete.

Sometimes her father came up too and tried to sing to Noname, blowing smoke from his cigar toward the window, rocking her with one hand, gazing at her in the box of the crib, wondering into what boxes she would grow.

Daddy, she said in her mind, even as a toddler, gazing at his distracted smile. He heard her voice, her need to reach him and looked down. Listen, she said. Listen. He went away puffing, smiling.

She had to listen for him, for all men, brothers, poets, writers, artists, musicians, who did not make room for women, who did not understand the perfect juxtaposition their intention makes on all art, their intention to make peace, create even in havoc, out of havoc, for havoc.

Pom pam pom pam pom. Pom pam pom pam pom went her mother’s bare feet climbing stairs to her room toward the crib in which she lay naked surrounded only by breeze that blew over her the scent of metal, sky, trees, trucks and debris, scent that demanded music transform it into something beautiful. A curtain puffed derided by wind, brushed her cheek and she billowed.

__________

A note from the publisher:

In July of 2012, Arya Jenkins’ short story “So What”—a story about an adolescent girl who attempts to connect to her absent father through his record collection – was chosen as the 30th winner of the Jerry Jazz Musician Short Fiction Contest. When that outstanding work was soon followed up with another quality entry with jazz music at its core, I invited her to contribute her fiction to this website on a more regular basis. We agreed to a commission of three stories per year, and today’s publication of “The Piano Whisperer” is her 15th story to appear on Jerry Jazz Musician. To access all of her work, click here.

I recently received word from Ms. Jenkins that Fomite Press, a small, independent publisher out of Vermont whose focus is on exposing high level literary work, will be publishing these stories in a collection titled Blue Songs in an Open Key. Publication date is November 1, 2018.

I am pleased that the investment we made in one another has led to such a proud result.

For more information about the book, and about Ms. Jenkins, visit her website at www.aryafjenkins.com.

Joe Maita

Publisher

Jerry Jazz Musician

_____