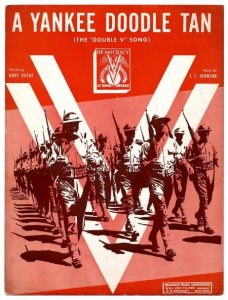

The sheet music to “Yankee Doodle Tan,” by Andy Razaf and J. C. Johnson (1942)

_____

While the civil rights movement may not have officially begun until the December, 1955 day that Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat to a white man on a Montgomery, Alabama bus, the stage for it was set years before that. Religious leaders and institutions, jazz and athletics all famously played important roles in building a foundation for the movement, but the hypocrisy of the United States during World War II, when African-Americans were expected to shed blood overseas to preserve freedom for those who often oppressed them in this country, increased pressure on politicians to desegregate the one institution at the center of American life – the military.

In my 2003 interview with David Colley, author of Blood for Dignity: The Story of the First Integrated Combat Unit in the U.S. Army, he said that by World War II, “blacks had had enough of discrimination and segregation, and with the advent of the war and their continued relegation to second class citizenry — even while fighting allegedly for freedom while they themselves were subjugated — pressure for reform in American society was growing. More people in America were starting to realize that it was just intolerable to continue this way.” The pressure to respond to this intolerable hypocrisy was felt in Washington, and, three years after the war concluded, in July of 1948, President Harry Truman issued Executive Order 9981, which ended segregation in the Armed Services.

I have been spending some time with a fascinating book by Tracy Fessenden, currently the Steve and Margaret Forster Professor in the School of Historical, Philosophical, and Religious Studies at Arizona State University. Her important work is titled Religion Around Billie Holiday (Penn State Press, 2018), in which she examines the influence religious life had on Lady Day’s life and career. A gifted scholar and enlightening writer, Professor Fessenden occasionally visits the history of race and American music as it connects to Ms. Holiday’s biography, reminding readers of major events in the world of music that had an influence on societal change.

A prominent story she tells, and one that may not be commonly known, is of the “Double V for Victory” campaign, inspired by a 1942 letter to the Pittsburgh Courier by James G. Thompson, in which the African-American writer asks, “Would it be demanding too much to demand full citizenship rights in exchange for the sacrificing of my life?” Thompson proposed that in his campaign, “the first V for victory” is “for victory over our enemies from without, the second V for victory over our enemies from within. For surely those who perpetrate these ugly prejudices here are seeking to destroy our democratic form of government just as surely as the Axis forces.”

In this outstanding excerpt from Religion Around Billie Holiday — the quality of which is indicative of what the reader will experience throughout her book — Professor Fessenden writes about how the likes of Lady Day, the Ink Spots, John Hammond, Andy Razaf, Lionel Hampton, and the Golden Gate Quartet all figured into this important civil rights history. The excerpt begins with a reference to the “From Spirituals to Swing” Carnegie Hall concert of 1938, a showcase of African-American music from its spiritual origins to the swing music popular at the time, and produced by John Hammond, an influential figure in 20th Century American music as record producer, critic, activist, and impresario.

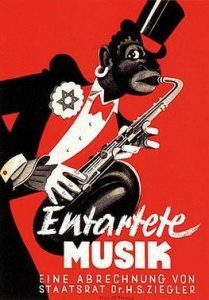

The poster for the Nazi-organized “Entartete Musik” (“Degenerate Music”) exhibit (1938), which vilified jazz as a black-Jewish hybrid

_____

Excerpted (with permission of the author) from:

Religion Around Billie Holiday (Penn State Press, 2018)

by Tracy Fessenden

In the year that “From Spirituals to Swing” was first produced in New York, Nazi officials in Germany organized a traveling exhibit called Entartete Musik, “Degenerate Music.” Entartete Musik vilified jazz as a black-Jewish hybrid, symbolized in the exhibit poster by a dark-skinned and simian-featured saxophonist with a Jewish star on his lapel. The image was meant to refer to the protagonist in Jonny Spielt Auf (Jonny Strikes Up), Austrian composer Ernst Krenek’s 1927 opera about a black jazz musician. The opera’s eponymous “Jonny” served the organizers of Entartete Musik as shorthand for black musicianship, and Jonny’s enabling fan base as a marker for Jews. As the exhibit’s program put it, “A people that nears hysteria in its praise for ‘Jonny,’ who has already shown off much too long for that people, has grown spiritually and mentally ill, and is internally confused and unclean.” As an instrument of propaganda, Entartete Musik was a testament to American jazz’s global reach and a backhanded benediction on Café Society, the integrated Greenwich Village nightclub that former shoe salesman Barney Josephson, a second-generation Lithuanian Jew, opened that year with Hammond’s backing.

Café Society was where Billie Holiday first sang “Strange Fruit.” Hammond described the club as “an extension of my Spirituals to Swing,” a venue “where known and unknown performers could be heard, where jazz and blues and gospel were blended,” and where “Negro patrons were as welcome as whites.” Because many of the artists Hammond brought to New York in 1938 for “Spirituals to Swing” stayed on to play at Café Society, the concert was reprised at Carnegie Hall a year later. Benny Goodman and Arthur Bernstein joined the 1939 lineup, making a roster of black and Jewish talent to which the Nazis could point in confirmation of their screeds.

For all that Hammond and Josephson sought to lift the racial barrier, audiences at Café Society and both Carnegie Hall concerts were almost entirely white; the black musicians they sponsored, meanwhile, needed daily to navigate the indignities of segregation that structured everyday life in the North as well as the South. As “Spirituals to Swing” neared production, Billie Holiday was performing with Artie Shaw’s all-white band at New York’s Lincoln Hotel, where she was forbidden to drink at the bar or sit on the stage, made to enter and exit through the kitchen, and directed to wait by herself in “a little dark room” between numbers. In the following year Holiday began to close each of her sets at Café Society with “Strange Fruit.” It was a delicately orchestrated ritual, and a trademark she retained for the rest of her career. Waiters stopped serving and stood still; the lights were cut but for a pin light trained on Holiday’s face. When the room had quieted to the requisite anticipatory hush, her accompanists started in on the muted opening chords. A reviewer for the New York Post described the sound:

“Southern trees bear a strange fruit . . . blood on the leaves and blood at the root,” begins Billie, and the long, mournful melody on the horns, which introduced her, instantly takes on the quality and remembrance of a dirge. “Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze, strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.” Then there is Sonny Whit[e] on the piano before she takes up again, playing softly as death.

“Pastoral scene of the gallant South . . . the bulging eyes and the twisted mouth.” She sings with a curious lack of emphasis, dropping each word slowly and without accent. . . .

The result is a desperate and dreadful intimacy between hearer and singer. “I have been entertaining you,” she seems to say. “Now you just listen to me.” The polite conventions between race and race are gone.</ext>

In their place, “a terrible explosion of sincerity” has “occurred within the confines of a set and rigid and meaningless form,” and has “blasted it to bits.”

“Strange Fruit” had had its start as a poem (“Bitter Fruit”) by Jewish teacher and labor activist Abel Meeropol, who wrote under the name of Lewis Allan. “When [Meeropol] showed me that poem,” Holiday explained of “Strange Fruit,” “I dug it right off,” because it “seemed to spell out all the things that had killed Pop” — jazz guitarist Clarence Holiday, who died at age thirty-nine after falling ill on tour in Texas — and because “the things that killed him are still happening.” Holiday believed her father’s lungs had been damaged by exposure to poison gas when he served overseas in the First World War. When he was finally admitted to a hospital in Dallas, his lungs had hemorrhaged; Holiday said the shirt of his bandstage tuxedo was stiff with blood when she collected his body. In an interview, Holiday described her father’s death for want of care as “being murdered by race prejudices, by the cold of heart. . . . It was another typical ‘pastoral scene of the gallant South.”

Two years after Holiday recorded “Strange Fruit,” a black soldier, Felix Hall was found bound and hanged in a ravine near Fort Benning, Georgia, where he’d been training to fight overseas. In January 1942 the African American Pittsburgh Courier published a pointed letter from a reader. “Should I sacrifice my life to live half American?” asked the writer, James G. Thompson. “Would it be demanding too much to demand full citizenship rights in exchange for the sacrificing of my life?” These questions, Thompson said, “need answering.” In the meantime, he made a proposal.

The V for victory sign is being displayed prominently in all so-called democratic countries which are fighting for victory over aggression, slavery and tyranny. If this V sign means that to those now engaged in this great conflict then let we colored Americans adopt the double VV for a double victory. The first V for victory over our enemies from without, the second V for victory over our enemies from within. For surely those who perpetrate these ugly prejudices here are seeking to destroy our democratic form of government just as surely as the Axis forces.

With Thompson’s letter the Double V campaign was launched. Double V clubs, Double-Victory gardens, Miss Double V contests, and Double V hairstyles all contributed to the effort. The nation’s largest union, the United Auto Workers, unanimously endorsed the Double V campaign “for a victory over the forces of Fascism and reaction and oppression both within this nation and in the world at large.” The National Baptist Convention urged members to make Easter Sunday 1942 Negro Double V Day, and the Courier obliged with an artist’s rendering of the risen Christ holding a V in each hand.

The Double V campaign was a delicate balancing act. It was in the first place a bold setting forth of terms: If we are asked to fight for the nation’s freedom, we will accept nothing short of full equality. Otherwise, as a Courier editorial put it, “it does not make a great deal of difference what happens abroad.” The Double V was at the same time a plea for more combat assignments for black soldiers, and so in effect an offer of blood sacrifice in the cause of still tentative and incomplete citizenship. Subtle weighing of the terms of the deal might erode conviction. What was needed, said a columnist for the Courier, was spirited music about the Double V that would give black Americans “a chance to sell our selves to our citizenry via the radio.”

Enter the formidable pairing of Andy Razaf and J. C. Johnson, who separately and together contributed memorable songs to Billie Holiday’s oeuvre: “Trav’lin’ Alone” (Johnson), “Blue Turning Grey over You,” and “Gee Baby, Ain’t I Good to You” (both Razaf). Holiday recalled that a “fellow named Razaf” helped her with the lyrics for “Don’t Explain,” which the sheet music credits to Holiday and Arthur Herzog Jr. Johnson also wrote signature tunes for Bessie Smith (“Empty Bed Blues”), Ethel Waters (“You Can’t Do What My Last Man Did”), and Fats Waller (“The Joint is Jumpin’, co-written with Razaf). Razaf secured his place in the American Songwriters Hall of Fame with “Stompin’ at the Savoy,” “Ain’t Misbehavin’” (co-written with Fats Waller), and “(What Did I Do to Be So) Black and Blue,” which shows up as the protagonist’s interior soundtrack in the prologue to Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. Two of the very best in the business, Razaf and Johnson teamed up to write “Yankee Doodle Tan” for the Double V effort not long after Thompson’s letter was published. Lionel Hampton, his band renamed the Double V for the occasion, played it for an estimated two million listeners who heard it broadcast from the Savoy Ballroom by NBC radio that May. The Courier began selling the sheet music for “Yankee Doodle Tan,” billing it as the “most thrilling masterpiece ever set to words and music” and the noted songwriting duo’s “best work.” “The feeling and meaning that they have injected into ‘Yankee Doodle Tan’ comes forth with a clarity and brilliance that beggars description. Everything is in the song.”

You can see the Double V emblem on the sheet music for “Yankee Doodle Tan” in a photograph of the Ink Spots at the Savoy Ballroom in Pittsburgh sometime in 1942. Someone must have handed them the music to read a few moments before the picture was snapped. Half of the men in the group are laughing; the others look bewildered or annoyed, as though they were missing the joke. Ev’ry time I see a dusky soldier man / With that rhythm in his step and skin of tan, the lyrics begin,

I could build a monument up in the sky

On it I would carve these words that cry

He’s a Yankee Doodle Tan

A Yankee Doodle Tan

When others can’t that’s just the time he can

He’s a Yankee Doodle Tan

A Yankee Doodle Tan

A gay and plucky happy-go-lucky Yankee Doodle Tan.

James Baldwin observed that among the subtlest and cruelest effects of racial panic, “that terror which activates a lynch mob,” is to declare “it impossible that our lives shall be other than superficial.” Hence the fate of so many earnest representations of blackness mounted against racism, which is to remain “fantasies, connecting nowhere with reality, sentimental,” “trapped and imprisoned in the sunlit prison of the American dream.”

Remarkably, given its historical provenance, “Yankee Doodle Tan” has slipped almost entirely from the archives of sheet music and recorded sound. A lone, partial version survives in the movie Hit Parade of 1943, a wartime formula musical. Hit Parade of 1943 features in its final scenes a live concert broadcast on radio, with listeners phoning in requests along with their pledges to purchase war bonds. A request for “Yankee Doodle Tan” comes over the wires from a “Mr. and Mrs. Lincoln” of New York City, who pledge a $10,000 bond to hear the song performed by the Golden Gate Quartet, erstwhile singers of holiness hymns whom Hammond recruited for “Spirituals to Swing.” Onto the stage they stride in the full military dress of various units and ranks, marching in step to the vocals’ swoony homage to dusky men in uniform. It’s a jaunty shtick, the Andrews Sisters meet the Village People. There’s no ache in the music, no intimation that wartime sacrifice, tendered in the name of still elusive freedoms, might call on psychic investments beyond the register of good cheer. Gay and plucky, happy-go-lucky. Elsewhere in the film the quartet — Willie Johnson, William Langford, Henry Owens, and Orlandus Wilson —play a cook, a driver, a handyman, and a delivery boy, flunky roles typically given to black enlisted men. Of the half million black American soldiers serving in 1943, only about eighty thousand were stationed overseas; of these, only a handful saw combat, while the vast majority labored to transport, feed, and bury other soldiers.

In addition to the Golden Gate Quartet and the Count Basie Orchestra, the film’s black musical artists include Dorothy Dandridge, who was twice tapped to play Billie Holiday in separate film versions of Lady Sings the Blues. The production starring Dandridge was never made, though Dandridge went on to play a heroin-addicted jazz singer based on Billie Holiday in the 1962 TV crime drama Cain’s Hundred. Hit Parade of 1943 recruits several characters as foils to the Golden Gate Quartet’s spic-and-span embodiment of black potential: the step-and-fetch-it janitor who inspires the hit song “Harlem Sandman”; a work-averse little kid whose pretense of heading “the junior colored commandoes” translates black wartime service into minstrelsy (“we work at night on account of when the enemy see us, he think we just ain’t there”). Even the dancing Harlem Sandman in Basie’s stage show is a proto-rapper in a pimpmobile who blankets uptown in narcotic dust.

The real Harlem, meanwhile, was swimming with cops: “on foot, on horseback, on corners, everywhere,” James Baldwin remembered of the summer of 1943, “always two by two.” The trouble had started in April, just as Hit Parade of 1943 was released. The Savoy Ballroom, where Lionel Hampton and Billie Holiday had recently played a “Miss Victory” benefit for the American Women’s Voluntary Services, was deemed the vector for 164 cases of venereal disease among mostly white servicemen and shut down. A tense spring and summer turned violent on August 1 when a white policeman shot a uniformed black soldier. The soldier, Robert Bandy, had tried to stop the cop from arresting a black woman in the lobby of the Braddock Hotel, where Holiday lived off and on in the 1940s. Riots and looting spread with the news of Bandy’s shooting. Within twenty-four hours, six thousand additional police officers were stationed in Harlem, hundreds of people were wounded, and six lay in the morgue, five of them killed by police. A volunteer with Harlem Hospital’s U.S. Ambulance Corps Unit remembered the emergency room floor that night as ankle-deep in blood.

Robert Bandy became the anti–Yankee Doodle Tan, a reminder of injustices heaped on African Americans in and out of uniform and an embodiment of the Double V’s remoteness from their lived experience. Langston Hughes put a point on it in “Beaumont to Detroit: 1943”:

Looky here, America

What you done done–

Let things drift

Until the riots come

……………………..

I ask you this question

Cause I want to know

How long I got to fight

both hitler and jim crow.

Eleanor Roosevelt would compare the structural oppression of African Americans in her lifetime to “the kind of thing the Nazis had done to the Jews in Germany.”

_____

Excerpted (with permission of the author) from:

Religion Around Billie Holiday (Penn State Press, 2018)

by Tracy Fessenden

(Professor Fessenden and H. Cooper Harriss, Assistant Professor in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of Indiana, and author of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Theology, will join me in November in a discussion about the religious lives of Ms. Holiday and Mr. Ellison. The conversation will be published on Jerry Jazz Musician in December, 2018.)

*

A very informative article and all so sad