.

.

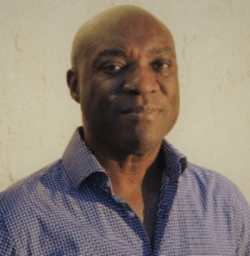

Winston James, author of Claude McKay: The Making of a Black Bolshevik [Columbia University Press]

.

.

___

.

.

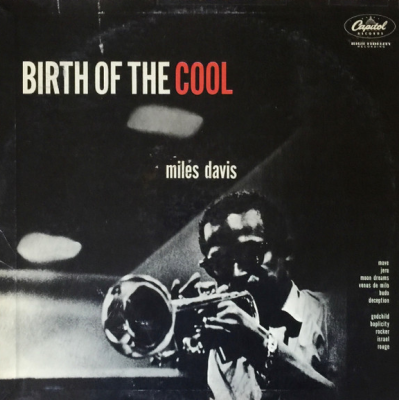

…..When one thinks of the key figures of the Harlem Renaissance (1917-1930), names like Louis Armstrong, Langston Hughes, Duke Ellington, Zora Neale Hurston, Fats Waller. W.E.B. DuBois, Alain Locke, Jacob Lawrence, and Billie Holiday come immediately to mind. Their contributions to arts and letters throughout the 20th century are well-chronicled and appropriately revered.

My very tattered copy of Black Voices: An Anthology of Afro-American Literature

…..I became intrigued by the era of the Harlem Renaissance during my youth. While discovering the depths of my initial fascination with jazz music, these artists were part of my early education. I’d dig deep into the catalogs of Armstrong and Ellington, read about the venues in which they played, what they recorded (and with whom), and ultimately explore the interest I had developed from the experience of discovering their work. A key guide at this time of my life was the book Black Voices: An Anthology of Afro-American Literature, a collection of writings by the likes of Ralph Ellison, James Baldwin, Richard Wright, James Weldon Johnson, Hughes, and Paul Laurence Dunbar. The anthology served as a launching point for much of what has captivated me about Black history, and for my subsequent belief that you can’t understand American history without also understanding Black history.

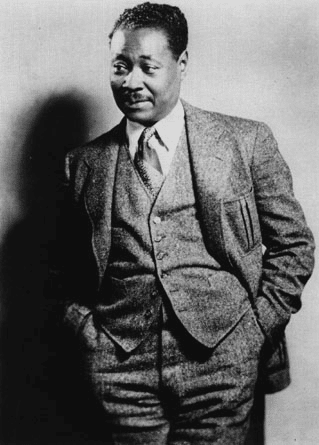

…..It was in this book where I first discovered the poet Claude McKay, who Winston James, author of Claude McKay: The Making of a Black Bolshevik describes as “the most controversial figure of the Harlem Renaissance.” McKay, born in a small Jamaican village and the youngest of eleven children, lived all over the world. During the years of McKay’s life James’ book covers (1889 – 1921), he left the West Indies for America in 1912 to attend Tuskegee University and then Kansas State University (to study agriculture), lived in New York from 1914 – 1919 (when he began to devote his life to literary and editorial activities), traveled to London (where his commitment to revolutionary socialism deepened) and eventually to the Soviet Union (where he participated in and spoke to the Fourth Congress of the Communist International in Petrograd and Moscow).

…..According to James, McKay was controversial because he was “reviled and loved in equal measure but for different and incommensurate reasons. To the younger Harlem writers, especially Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston…McKay was a hero worthy of emulation and celebration.” Hughes said that “it was McKay’s example that started me on this [poetry] track.” And the novelist Wallace Thurman described McKay as “such an intense person that one can often hear the furnace-like fire within the roaring of his poems,” a writer who possessed “more emotional depth and spiritual fire than any of his forerunners or contemporaries.” However, others, like the conservative Black writer George Schuyler, called McKay a “black fascist” because of his embrace of socialist political ideology.

…..McKay was a celebrated poet whose first poems – published in 1912 in the collection Songs of Jamaica – consist of dialect verse and were very popular in that country. James’ outstanding biography tells of this era of his life and ensuing work, and also serves as a well-researched and enlightening history of the African diaspora through one man’s significant life experience. James covers McKay’s childhood so influential to his career, and also how his politics showed up in his poetry, including his most famous work, “If We Must Die,” published during the “Red Summer” of 1919 – a period of intense racial violence against Black people in America.

…..In an August 22, 2022 interview, Mr. James talks with me about this revolutionary, non-conformist figure and his complex early life that culminated in a pioneering role in American letters. I hope you enjoy…

Joe Maita

Editor/Publisher

.

.

___

.

.

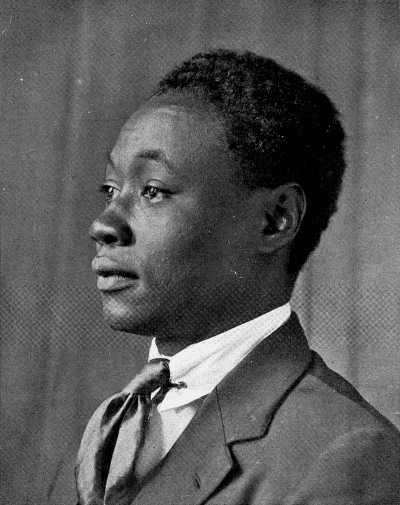

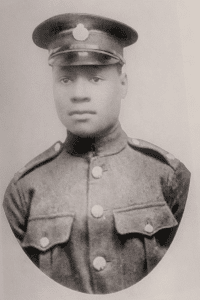

Claude McKay in 1920

.

A key part of [McKay’s] life’s work – largely in spite of himself – was an unrelenting meditation on what it meant to be Black in a white man’s world, a world dominated by Europe and its far-flung diaspora. In McKay’s work we have one of the most intellectually rewarding, sustained, and engaging ideologies of Black liberation – Black nationalism and socialism. The product of his diligent search for political strategies in the fight against the oppression and exploitation of Black people around the world, the tension between the two projects – both of which, in varying combination, simultaneously commanded his sympathy – characterized his work to the end of his life.

-Winston James

.

Listen to Claude McKay read three of his poems: “If We Must Die,” “Issac’s Church Petrograd,” and “The Tropics in New York”

.

___

.

JJM You have made the study of Claude McKay a major part of your life’s work, this being your second book on him. Why should readers be interested in Claude McKay?

WJ It’s partly because of his perspective, his intelligence, his extraordinary capacity for analysis, and the way in which the issues that he wrestled with during his lifetime are still current – racism, imperialism, sexism, homophobia, and white supremacy in various forms. He also in many ways teaches us the art of living fearlessly, courageously. I find it remarkable the extent to which he operated without fear even when he us very vulnerable himself and often in defense of the humanity of black people. At the same time, he managed to maintain his own humanity and sense of decency, and didn’t become cynical or bitter or dismissive. He recognized that life was rough, but he also recognized the beautiful aspects of human life. So, he was extraordinary, and he has been a very good and wise companion. And yes, I’ve been living with him for many years now. I never do get bored of him.

JJM McKay was from Jamaica. Where are you from?

WJ I was born in Jamaica, and partly grew up there before moving to England, where my parents had migrated, and where I grew up before coming to the United States. So, there is that connection between me and Claude McKay. Because my parents are Jamaican and I was brought up in Jamaica and lived there into my teen years, I have a good understanding of the language—my mother tongue, as it were — and the mores and the different dimensions of the culture that existed during McKay’s time and were still there when I was growing up. I almost invariably find that the subtlety of the language and the nuances of the culture escape the understanding of non-Jamaican and non-Caribbean commentators.

JJM You point out that Wayne Cooper’s 1987 biography of McKay is the only full length biography of him. This volume of your work is not intended to be a full-length biography, rather it is a look at the events and circumstances that shaped his political views from the time he was born in 1889 until 1921, when he returned to the United States from London. Are you writing another book that takes on his life after that?

WJ Yes, this volume of his biography goes up to the beginning of 1921, which is substantial enough to stand on its own, and it is a good place for a break in his life’s story. In this particular volume I wanted to show his radicalization and his political trajectory up to the time that he embraced Bolshevism, when he became enamored with the promise of the Russian Revolution. So, this book covers his life up to that point, and the second volume will cover from 1921 up to his death in 1948, a period in which his trajectory became more Black nationalist in outlook, in part because of his disillusionment with the American left. But those are topics that will be addressed in the next volume, and I’ll also look at his novels and other work during that period.

JJM You wrote that new material made available since Cooper’s book was published “radically alters previous portraits of McKay.” How so?

Claude McKay: Rebel Sojourner in the Harlem Renaissance, Wayne Cooper’s 1987 biography of McKay

.

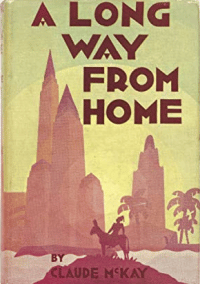

McKay’s 1937 autobiography

WJ There are a number of areas in which this is the case. One is in relation to his time in England. For whatever reason, in his travelogue-cum-autobiography A Long Way From Home, his time living in London is not entirely reliable. It could be that when he wrote the book in 1937 he was trying to suppress some of the more radical dimensions of his activity there at the time. We did know about his connection with the radical newspaper Workers Dreadnought and his publications within it, but what we didn’t have was access to his correspondence with Charles (C. K.) Ogden of Cambridge Magazine. He was the man who shepherded McKay’s first post-Jamaica publication, Spring in New Hampshire, which came out in London in 1920. I was the first McKay scholar to discover and comment upon Ogden’s correspondence with McKay, which was an extraordinary find consisting of a rich cornucopia of letters that deal with McKay’s daily experience in London – the racism he encountered, the way in which he was attacked by racists in the streets of London, his experience of working with Sylvia Pankhurst on the Workers Dreadnought, and his time at the International Socialist Club. He often wrote Ogden one letter per day, and the collection is extraordinarily rich in terms of understanding the full texture of his British experience – and this collection of letters was never known to McKay scholars until I came across it in a Canadian university archive in the late ’90s. I mentioned the collection in an essay on McKay published in 2003. So, that correspondence, acquired by McMaster University between 1980 and 1997, wasn’t available when Cooper wrote his biography.

There is also information from the Russian archives that became available after Glasnost, revealing a deeper understanding of McKay’s involvement with the left and when he went to Moscow in 1922-1923, which I will go into in more detail in my next volume. There are also the Marcus Garvey Papers that came out since Cooper’s biography was published – an extraordinary set of 13 volumes of the Marcus Garvey Universal Negro Improvement Association Papers that were edited by Robert Hill at the University of California, Los Angeles. These have given new perspective on the Garvey movement, as well as McKay’s engagement with it. And then there’s the material around the African Blood Brotherhood – including its organ, the Crusader – that was lost for a long time, as well as Justice Department intelligence reports and other materials that were released under the Freedom of Information Act. So that gave me a lot to work with, and it is one of the reasons why it took awhile to get this book together.

JJM Your book is broken up into three parts, the first of which deals with McKay’s youth in Jamaica, his family, his class and the Black peasantry into which he was born, and how he fit within the social structure and political economy of the island. Who were his childhood role models that had an influence on his eventual worldview?

National Library of Jamaica

U. Theo McKay

WJ His oldest brother U. Theo (born Uriah Theodore), who actually raised him, was his greatest influence. His parents agreed that U. Theo would raise Claude, which he did from the time Claude was seven until he was 14. U. Theo lived near Montego Bay in the western part of Jamaica, some distance away from where their parents lived (Clarendon). U. Theo, who was seventeen years Claude’s senior, was a remarkable man, quite brilliant and insufficiently celebrated in his own right, but also in terms of his influence on Claude. He attended Mico College, which was one of the greatest teachers’ colleges in the Caribbean at the time, and then became a highly respected educator and headmaster in Jamaica.

Theo was unusual in a number of ways. He was a free thinker, and he was an atheist, which was very rare at that time. There were atheists in Jamaica – and I document the evidence of this from the Rationalist Press Association, which was the largest atheist organization in the world at the time – but U. Theo was extremely unusual in the sense that he didn’t have time for religion in an environment that was steeped in religion. He was also a Fabian socialist, subscribing to the ideas of Fabianism, which was a British socialist movement advancing the principles of democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist efforts rather than by revolutionary overthrow. He actually had their publications sent to him from England. U. Theo was also a staunch feminist who advocated for the suffrage being extended to women at a time when many of the Jamaican Black intellectuals didn’t feel women should be able to vote. He also wrote incessantly to the newspaper about the issues of the day.

So, he was extraordinary, and his courage in speaking out and holding fast to his views greatly influenced Claude, who wrote in his memoir that the greatest joy during his childhood was knowing that he was his brother’s brother. He really loved his brother, and his brother really loved him.

National Library of Jamaica

Walter Jekyll, c. 1890’s

Theo was always like a father to him, and when Claude went back to the village in which he was born he had to get reacquainted with his biological parents because he had been away from them for seven years, and during that time had only communicated by letter. The other person crucial to his development was his mother, Elizabeth, who Claude referred to as an extraordinarily generous, tolerant, open-minded, and compassionate person, especially in relation to the most dispossessed members of the community. Another important person was Walter Jekyll, the British aristocrat who encouraged McKay to write in his native Creole language. I have argued that Jekyll’s impact on Claude McKay is overrated, and is so at the expense of U. Theo. But Jekyll did have a role in McKay’s development, which is acknowledged by McKay and which I outline in the book. Although McKay never loved his father, he admired his sacrificing for the family, his hard work, racial pride, dignity and courage. So, these were his early important influences before he left Jamaica.

JJM Did he have an interest in writing poetry from a young age?

WJ Yes, he started writing poetry around the age of 10, when he was effectively the only child of his brother and his brother’s wife. His brother had a wonderful library which Claude read vociferously from and which inspired wonderful discussions between McKay and U. Theo. He also spent a lot of time reading and writing on his own, so I think that is where his interest in poetry began.

JJM Is there any evidence of who a literary hero of his would have been while he was in Jamaica?

WJ He was basically influenced by figures in British literary culture – the Scottish poet Robert Burns, for example, as well as William Shakespeare. Burns wrote in the Scottish dialect and became known as “Bobby Burns.” McKay is sometimes referred to as “Jamaica’s Bobby Burns” because he wrote in the Creole language, the local lingua franca. Burns was witty and funny and captured the everyday language of the people and experience of ordinary Scottish people, and McKay tried to do the same in relation to the Jamaican people.

JJM Where did Claude McKay fit within Jamaica society, and within its economy?

Claude McKay Collection, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

Thomas McKay, c. 1920’s

WJ He had a peculiar position within Jamaican society. He was Black with very dark skin, and he was also from a family that was relatively prosperous. His father, Thomas, signed his name on McKay’s birth certificate with an ‘X’, which suggests that he couldn’t write and was likely illiterate, but there were people who later claimed that he read the Bible and remained vibrant into his old age. But the hard evidence suggests that he was in fact illiterate. Thomas was very shrewd, prudent, and extraordinarily hard working, and he received a couple acres of land from his father-in-law when he married his wife, Elizabeth. By the time Claude left Jamaica in 1912, his father had accumulated over 100 acres of fertile land, as well as sophisticated machinery from the United States, animals, and carts. So, he had become quite prosperous. And, all seven of Thomas’ children went through the education system, and virtually all of them became professionals of one kind or another.

I mentioned the darkness of Claude’s skin because in Jamaica and in much of the Caribbean at the time, the darker you were, the lower down the social ladder you were. It’s as if you could read off one’s color and class in one grid; if you were dark, you were working class; if you are light-skinned, you were likely of mixed descent and thus in the middle class, above the dark-skinned working class people; and if you were white, you were in the upper class. So, you didn’t see white people doing manual work, for instance, in the Caribbean. This class positioning was reproduced over and over again with each generation, and into the 20th century; arguably up to the 1970s.

So, the McKay family were very peculiar in the sense that, based on their dark skin, they came from the most oppressed layer of the Caribbean and Jamaican working class, yet they inhabited a place in the professional and middle class. Partly because of that U. Theo wrote many progressive and critical letters and articles in the Jamaican press concerning the working class and the peasantry, and his concern for the lower classes was very much related to the proximity of his class position to that of the working class because his father had come out of that. (Thomas had been a road mender, one of the most lowly position within the social hierarchy.) That memory of their class position and the experience of living within it was very much alive in the family, and they all resented the colorism and the racism that they encountered, especially from the lighter-skinned, non-European members of society. So, it’s a very interesting position that helps explain the beginnings of their questioning of the social structure. And when Claude McKay went into the constabulary [police] force and saw how it operated, he became even more radicalized.

JJM What enduring effects did his time as a policeman have on him?

Frontispace, Songs of Jamaica

Claude McKay in constabulary uniform, 1911

WJ His time as a policeman was quite profound, and it made his radicalism more entrenched. While he had a radical predisposition because of his brother and his Fabianism, his experience in the police force – where he witnessed the force being used against poor, dark-skinned people like himself, and the way light-skinned police officers treated dark-skinned recruits – profoundly affected him. Being a member of the constabulary was one thing that he did in his life that he regretted, and it emerges in his poetry, in his autobiographical short story “When I Pounded the Pavement,” and in all of his dealings with established authority, including when he was in the United States. He had a sympathy for people he called “wrong doers.”

JJM Yes, he wrote about prostitutes quite a bit…

WJ Yes, because these are people he encountered when he was a police officer, and one of his friends from his childhood in the countryside ended up dead in a brothel in Kingston. The impact was so profound that he wrote a long, moving poem about her death.

JJM What influenced his decision to go to the United States?

WJ It’s very strange, actually. He says that the United States was seen as the land of possibility, a vibrant, energetic land, unlike Europe. Because of the British colonial connection with Jamaica you would have thought he would go to England, but he was very adamant about the energy in the United States and his attraction to it despite the racist horrors that were taking place there, not only in the South but there was a fair amount of racism in the North also. Despite that, he felt that America was the place he wanted to go.

The other thing influencing his decision was that he wanted to be close to the Jamaican peasantry and sought to learn what he called “scientific agriculture,” which is what he went to Tuskegee University to study. So, he came to the United States in 1912 as a student, not as an ordinary immigrant. Tuskegee is in Alabama, which, of course, is not the most congenial place – not only because of the racism, but also because of the institution’s conservatism under the leadership of Booker T. Washington. That alienated him very quickly, so he left Tuskegee before his term even began. He arrived at Tuskegee in the summer of 1912, and by September of that same year he transferred to Kansas State College in Manhattan, where he wished to continue his pursuit of studying agriculture. While there he also took classes in literature, which was of course his main love. After two years he dropped out of college and moved to New York, thanks to financial assistance from Walter Jekyll, where he started a restaurant with a friend in Brooklyn. It failed shortly after it opened. He quickly settled in Harlem.

JJM What were his immediate impressions of America?

WJ It was heartbreaking for him. He was shocked and horrified by the brutality of the racism in the United States, which he talks about in one of his earliest autobiographical writings, a piece published in Pearson’s Magazine in 1918. He wrote of his shock seeing grown white men oppressing Black people in the most brutal way, and of how seeing this led him to hate – “but to hate is to be miserable,” so he shifted from that, he said.

In my earlier book, Holding Aloft the Banner of Ethiopia: Caribbean Radicalism in Early Twentieth-Century America, I wrote about the way in which many Caribbean people who came from majority Black societies didn’t encounter the kind of racism at home that they did in the United States. They were just shocked and horrified, and many of those who came to America, especially from French Caribbean colonies, apparently went mad – some even committed suicide because the horrors of racism were so profound.

So, that’s one of the reasons why there was this climate for radicalization, and also because there’s the lack of connection between the type of skills that they bring from Jamaica and the type of jobs that were open to them. Black Caribbean teachers coming to America discovered that they could earn far more on a construction site in Manhattan than they could as a respected teacher or headmaster in the Caribbean.

But the racist experiences – one of which, the 1918 lynching of a pregnant woman named Mary Turner – were absolutely shocking, and McKay writes about it in his poetry.

JJM How did the racist mob attacks and lynchings of 1919 – events that make up what became known as the “Red Summer” – affect him, and how did it show up in his poetry?

Front page of the Chicago Defender; August 2, 1919

.

CC BY-NC 2.0/via Flickr

A Ku Klux Klan rally; Washington, D.C. (c. 1922)

.

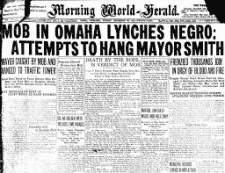

Front page of the Omaha World-Herald; September 29, 1919

WJ The summer of 1919 was made up of a series of racist attacks on Black people, I call them “attempted pogroms,” by white people who, at the conclusion of their service in World War I, returned to major cities and saw that there were more Black people in them than prior to the war, largely due to the fact that there were more opportunities for them to work in industry and earn wages not previously available. This led to an outburst of violence against Black people, including Black veterans of the First World War. This period is referred to as the “Red Summer” because much of this violence happened during the summer months, but it in fact began in April and became so expansive that it extends into 1920. There is new documentation that shows the attempted pogroms took place during this time in a total of over 30 cities, most notoriously Chicago and Washington, DC.

The Red Summer had a galvanizing effect on him. McKay was working on the railroads as a waiter at the time, and it is in that context that he wrote his most famous poem, “If We Must Die.” He was able to capture the mood of Black people who were under siege, but who were also willing to fight back. If we must die, let it not be like hogs/Hunted and penned in an inglorious spot/While round us bark the mad and hungry dogs/Making their mock at our accursed lot. And it goes on, and it ends with Pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back! That is what was happening, and the Black veterans of World War I were at the vanguard of the struggle against the racist mobs. There is good documentation showing the remarkable and noble resistance they put up in defense of the Black community, especially in Washington, D.C., Chicago, and Longview, Texas.

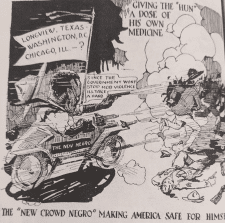

JJM “If We Must Die” was written during the emergence of what was known as “The New Negro,” Black Americans who were open to a more militant response to the events of the Red Summer. So, this poem was well received at the time…

“The ‘New Crowd Negro’ Making America Safe for Himself”; The Messenger magazine, 1919

WJ That’s right. The term “New Negro” was largely developed by the writer and political activist Hubert Harrison during the First World War. It was adopted by Alain Locke for the anthology he published during the Harlem Renaissance in 1925, but that book is not related to the original term of “New Negro.” The “New Negroes” were militant Black people fighting back and engaging in politics, and some of those people also wrote poetry, novels and short stories – McKay and Langston Hughes being important examples. But we shouldn’t confuse the art with the militancy – the militancy came first and it is how the “New Negro” was defined by people like Harrison.

So, at this time “If We Must Die” became the anthem of the “New Negro” and its movement, and the idea was to fight back. “Uncle Tom is dead” was one of the slogans of the time. This also comes into being after what people now refer to as “the horror of East St. Louis,” which took place in 1917, when Black people of that city were disarmed by the police and basically slaughtered in a horrible massacre. From those horrors they learned that they should arm themselves and defend themselves as aggressively as possible. Hubert Harrison talks of “an-eye-for-an-eye,” that if you are attacked you have to defend yourself and fight back. This is a new psychology that developed as a result of the migration of Black people from the South into places like Harlem, the south side of Chicago, and Pittsburgh. There is a new sort of freedom that they enjoyed because of the higher wages they earned in these cities, which in turn created the opportunity for a more open discussion concerning the plight of Black people.

JJM How did the white literary establishment critique “If We Must Die,” and how did the government respond to it?

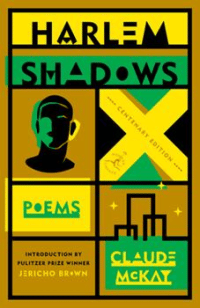

The 2022 Modern Library edition of McKay’s collection of poetry, Harlem Shadows

WJ I don’t believe there was any direct response to it by the white literary establishment. But it should be noted that the poem was first published in the white socialist magazine, the Liberator, edited by Max Eastman. The poem was reprinted in virtually every black newspaper and magazine in the country. The poem was reprinted in a volume that McKay put out in 1922 called Harlem Shadows, which was very well-received. The authorities – A. Mitchell Palmer from the Justice Department, for example – wrote a report about militancy among Black people, and McKay’s poem was cited often within it. Soon after that, McKay left for England.

JJM Did the government regard McKay as being seditious?

WJ They regarded him as being completely seditious, and it’s remarkable that he wasn’t arrested and deported.

JJM When did McKay begin feeling that socialism was an effective and promising vehicle to achieve the goal of Black liberation?

WJ It actually started with the Russian Revolution in 1917, but it was especially triggered in 1919 – the same year as the Red Summer – when the Communist International was formed in March and actually called upon the working class of the world to fight against imperialism and colonialism and racism, which attracted a significant number of Black people. There was an extraordinarily positive response to the Russian Revolution by radical African Americans, and the key to that response was the way in which “The Jewish Question” was dealt with in Russia by the Bolsheviks, who during the Revolution and civil war went after the progromists and “White” forces who were profoundly antisemitic. That won the support of people like A. Philip Randolph in the Messenger magazine, Cyril Briggs in the Crusader, and William Bridges in the Challenge. Marcus Garvey was also supportive. So, McKay saw the revolution as a template for Black emancipation in the United States, especially as it was articulated by Lenin and Trotsky. Russia became his “golden hope.”

JJM The horrors of World War I had a great impact on him…

WJ Yes, the global slaughter and mindless killing of young people in Europe and elsewhere was shocking to him. Having been brought up in the colonial Caribbean, he remembered the arrogant Victorian idea of “progress,” that people would become more humane, civilized and enlightened. But the cataclysm of World War I had a profound impact on him because it shattered all of that; he didn’t think that it could have happened. The Bolsheviks and the Bolshevik Revolution and its anti-imperialist views provided him with an alternative worldview, which meant his interest in the gradual shift to a Labour Party type of socialism professed by the Fabian socialists was replaced by something more radical. He began to describe himself as having “become Bolshevik.”

JJM He left the United States for London in 1919. How did his time there accelerate his political development?

Sylvia Pankhurst, c. 1910

WJ Well, he became more Bolshevik. He left the United States as a budding Bolshevik, but it became more mature and more developed in Britain because of the milieu in which he operated. He worked with Sylvia Pankhurst on the Workers’ Dreadnought, one of the first and most fervent supporters of the Russian Revolution. McKay was also a member of the International Socialist Club, a group he described as a “nest of extreme radicalism,” which included anarchists, Communists, Bolsheviks, and Wobblies (members of the Industrial Workers of the World), among others. It was also when he started reading Marx more seriously, spending time reading Das Kapital in the British Museum and participating in discussions and debates in the Club. So, he became more radicalized and got to know members of the British labor movement. The Irish struggle, for instance, was something that he sympathized with, which meant he was becoming more and more internationalist. He also frequently went to a club for Black veterans in central London – ex-soldiers from the Caribbean, Africa, India, and even some African Americans – who shared their feelings and experiences of war as well as the racism they encountered on the streets of London. This contributed to his radicalism and anti-Imperialism.

JJM He was shocked by the racism he encountered in England, which he had referred to as the “mother country.”

WJ Yes, and that’s why he became so bitter about the British, who he hated perhaps even more than white racists in America because he thought he belonged there due to his being brought up under the Union Jack. He sang “Rule Brittania!” during his childhood and on Empire Day regarded himself as British and, as you say, referred to England as the “mother country.” But while there he encountered racism everywhere. He would go with friends to pubs who refused to serve him, and was refused any long-term accommodations. The lodgings he was able to get during his 12 months in England were from foreigners – a German family, a French woman, and an Italian – so he never managed to live in a British household, and the accommodations he was able to get was a result of his connection to the International Socialist Club. So yes, it was a sad and bad experience for him in London.

JJM McKay wrote nostalgically of Jamaica while he was living in London…

WJ Yes. He wrote about his mother, about a river he used to bathe in, and he even wrote about the “Tropics in New York,” a powerful poem of nostalgia, while he was in England. During this moment he turned to nostalgia as a way of dealing with the darkness, and with his profound disillusionment with Britain.

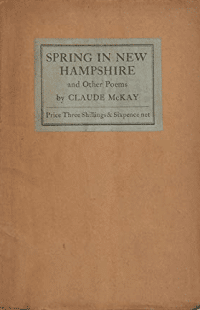

Spring in New Hampshire and Other Poems, McKay’s 1920 collection

JJM While he was in London, and in the midst of his being radicalized, his collection of poetry Spring in New Hampshire was published. He left the selection of the poems to be included in it up to C.K. Ogden, and the result is a collection of apolitical poems that was unrepresentative of his work at the time. It was more Ogden’s selection than McKay’s – and even “If We Must Die” was left out of the collection. Why did McKay allow that to happen?

WJ He fought with Ogden over everything having to do with this collection. He didn’t like the title of the collection and suggested alternatives, one of which was “Songs of Struggle.” But Ogden was very averse to including the radical poems in the collection, and the only one that survived was “Exhortation,” which exhorted Black people to “turn to the East,” meaning turn to the Russian Revolution.

I also think he was just worn out by his struggle with Ogden and therefore allowed it to happen, and he also wanted to leave England and have a book published before departing. It is puzzling as to why he allowed Ogden to choose the poems, but it is likely because he wanted to get back to the United States, and once he got to New York he arranged the publication of Harlem Shadows, in which he would restore all of his poems that were left out of Spring in New Hampshire. That collection was very well received.

JJM He became a celebrity in New York after the publication of Harlem Shadows, and was an influential, inspirational and, to some, a controversial figure at the center of the Harlem Renaissance…

WJ Yes, he was controversial. As he put it, he was “suicidally frank.” He was a radical, and compared to someone like Alain Locke, he was a firebrand. Stanley Braithwaite, a literary critic in Boston who often wrote for W.E.B. DuBois’ The Crisis, thought McKay was too radical, but the younger people loved him. Langston Hughes says that McKay was responsible for setting him on the track to becoming a poet. Wallace Thurman, Zora Neale Hurston and all of the younger generation loved McKay, who was very generous with his time and resources. He had a rich correspondence with them while he was in Europe, even after being in the United States. But, with the exception of James Weldon Johnson, the older generation felt McKay was too radical and generally shunned him.

JJM Johnson wrote of McKay, “Of all the Negro poets, McKay is the poet of passion.” Was that meant as a compliment?

WJ Yes, because of his capacity to write about the Black experience, for his ability to express a spectrum of moods – anger, sorrow, love, and beauty. Johnson was always very kind to McKay and helped him get back into the country in 1934, when he finally returned.

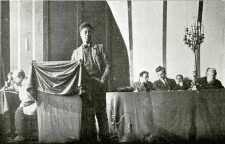

McKay, speaking in the Throne Room in the Kremlin; 1923

JJM McKay spent eight months of his life in Russia, and eventually became disillusioned about his experience there. Why?

WJ Mainly because of the rise of Stalin. He met and admired Trotsky during his sojourn in Russia. In addition, McKay’s closest friend in the United States was the Liberator editor Max Eastman, who was a translator of Trotsky. Eastman translated Trotsky’s History of the Russian Revolution and sent McKay a copy of the work (all 3 volumes), which deeply impressed McKay. McKay wrote in his autobiography A Long Way From Home about meeting Trotsky and how much he admired him. Stalin was not only thuggish and narrowly nationalist, but he also destroyed the anti-Imperialist thrust of the Russian Revolution, which alienated distinguished black radicals such as George Padmore who left the movement. Stalin’s persecutions and “purges,” McKay believed, tarnished the legacy and intentions of Lenin and the Revolution. He wrote a poem about Stalin in 1925, “We Who Revolt,” that was never published in his lifetime in which he called Stalin an “unctuous tyrant.” So, he felt disillusion with Russia in the aftermath of the rise of Stalin, and in his correspondence with Eastman he would ask about Trotsky, who had been sent into exile. But after the Second World War he became more ambivalent about Stalin because he saw him as a bulwark against the imperialist West.

JJM What can readers learn from Claude McKay’s life?

WJ McKay managed to see the world not only with his eyes but also through his exceptional intelligence, relentless analysis and courage. The extent in which he was so ahead of his time is also remarkable. He gives us – in my view more than anyone of his generation – a sense of how it felt to be a sensitive, Black person living in a white man’s world at a time when, with the exception of its non-white victims, white supremacy was taken for granted, normalized, and basically unquestioned in Europe and America. And what McKay actually gives us, too, is a sense of searching for an alternative to the world as it was and as it is, a capacity to dream despite the darkness, and a feeling that workers and oppressed people all over the world should align with one another in order to engage in the struggle against imperialism and capitalism. At the same time, he recognized the integrity of the Black experience, and the need for Black people to be proud of themselves, and struggle against racism while also engaging in political alliances across racial lines.

.

.

“…McKay was the most traveled member of his generation of Black intellectuals, spending more years abroad than any of his peers. After seven years in the United States (1912-1919), he spent fourteen years in Europe and North Africa between 1919 and 1934. All told, after leaving Jamaica for the United States in 1912, McKay spent no less than a third of the remainder of his life outside the United States. In addition to Jamaica and the United States, he traveled to and lived in at least nine different countries, developing varying levels of competence in several languages. And he made the most of his strangely unremitting itinerancy. A keen observer, he was forever analyzing his experience in letters, essays, novels, poems, a travelogue, and a memoir. He emerges as one of the most perceptive, sensitive and uninhibited analysts of the Black condition, especially that of the African diaspora in the United States and Europe, in the turbulent times in which he lived, a witness without peer.”

-Winston James

.

.

___

.

.

Watch the poet Kevin Young read McKay’s poem “If We Must Die”

.

.

Young talks about “If We Must Die”

.

.

___

.

.

Claude McKay: The Making of a Black Bolshevik

by Winston James

.

.

Winston James is the author of A Fierce Hatred of Injustice: Claude McKay’s Jamaica and His Poetry of Rebellion (2000); The Struggles of John Brown Russwurm: The Life and Writings of a Pan-Africanist Pioneer, 1799–1851 (2010); and Holding Aloft the Banner of Ethiopia: Caribbean Radicalism in Early Twentieth-Century America (second edition, 2020), winner of the Gordon K. Lewis Memorial Award for Caribbean Scholarship of the Caribbean Studies Association. He is also coeditor of and contributor to Inside Babylon: The Caribbean Diaspora in Britain (1993). James has held teaching positions in the United Kingdom and the United States, most recently as professor of history at the University of California, Irvine.

.

.

___

.

.

Praise for the book

“The wandering poet and revolutionary socialist Claude McKay was one of the twentieth century’s most captivating writers, noted for his intellectual intensity and emotional depth. Combining unparalleled erudition, literary sensitivity, and political nous, Winston James’s book provides a compelling and authoritative account of the life that McKay made and the circumstances within which he made it.”

– Peter Hulme, professor emeritus, University of Essex

.

“Meticulously researched and superbly written, this is the premier work on Claude McKay’s astonishing artistic range and diverse passions. It is also an incisive examination of the wider Jamaican and Caribbean colonial context, and a major contribution to the history of the Atlantic world, the Harlem Renaissance, and the overlooked connection with the founders of Négritude.”

– Franklin W. Knight, Leonard and Helen R. Stulman Professor Emeritus of History, Johns Hopkins University

.

“Elegantly written and carefully reasoned, this is a fascinating look at the political evolution of a key literary figure.”

― Publishers Weekly

.

“James is a perceptive literary critic, and his close readings are some of the most electrifying parts of The Making of a Black Bolshevik.”

– Jennifer Wilson ― Dissent Magazine

.

.

___

.

.

This interview took place on August 22, 2022, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita

.

If you enjoyed this interview, you may want to an interview with Jeffrey Stewart, National Book Award-winning author of The New Negro: The Life of Alain Locke

.

.

Click here to subscribe to the Jerry Jazz Musician newsletter

.

.

.

.