.

.

photo by Chris Hillman

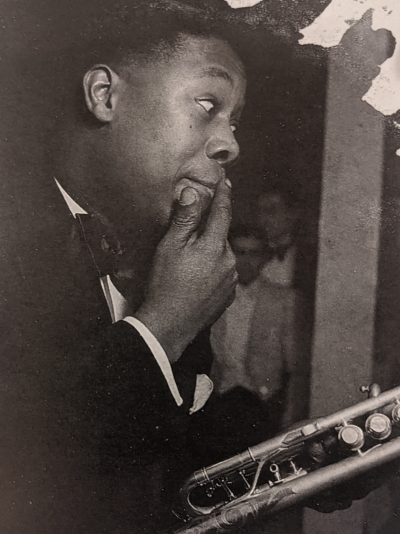

Travis Atria, author of Better Days Will Come Again: The Life of Arthur Briggs, Jazz Genius of Harlem, Paris, and a Nazi Prison Camp

.

.

___

.

.

…..The Grenada-born trumpeter Arthur Briggs was among the first to introduce and popularize jazz music, and did so from Europe, where he permanently settled after arriving from Harlem in 1919, and where he eventually grew to be considered “the Louis Armstrong of Paris.” Little-known in America, his musical biography features his befriending and performing with the likes of Sidney Bechet (who Briggs was with when he bought his first soprano saxophone), Josephine Baker, Coleman Hawkins, and Django Reinhardt.

…..Briggs was a musician of extraordinary talent whose impact on the music world is revealed in Travis Atria’s splendid biography, Better Days Will Come Again: The Life of Arthur Briggs, Jazz Genius of Harlem, Paris, and a Nazi Prison Camp. While music is a central part of Briggs’ life story, what Atria’s book most importantly uncovers is the musician’s courage in the face of racism and hatred during World War II, when he was arrested in Paris and sent to the Nazi prison camp at St. Denis, France, where he learned to survive the daily horror of his incarceration through the strength of his spirt and the gift of his musical talent.

…..The writer Gary Giddins calls Atria’s book a “nail-biter,” a “largely untold, often harrowing tale of jazz, race, and international politics” – a biography Atria hopes will “in some small way, serve as a reminder of how hard we once fought to defeat evil,” and that ignoring a history as complex as Briggs’ will be done so “at our own peril.”

…..In a May 7, 2021 interview with Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita, Atria talks about his book, and the man who was once considered to be “the greatest trumpeter in Europe.”

.

.

___

.

.

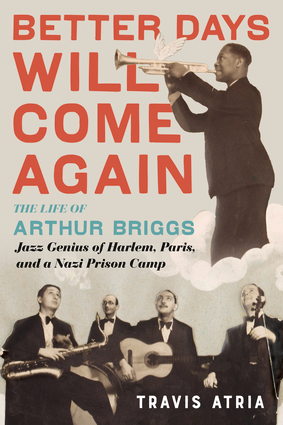

photo courtesy of Denis Pierrat/used by permission of the author

Arthur Briggs, sometime in the 1920s

.

…..There were teeth in the soup again, horse teeth. It was repulsive even to a starving man, and Arthur Briggs was a starving man. Hunger was a song stuck in his head as he shivered in a filthy hut, lice crawling on his skin. Evenings were once filled with jazz and risqué dancing, with gaiety and tumbling laughter, with champagne and fine cuisine. Now it was winter. He was hungry. And there were teeth in the soup again.

…..Briggs was trapped in Stalag 220, a Nazi prison for British citizens and other enemies of the Third Reich. Six miles south was Paris, where he had made his reputation as the greatest jazz trumpeter in Europe, earning the nickname “the Louis Armstrong of France.” But isolated here in this camp, he might as well have been on the moon.

…..He could have fled the Nazis. He had family in Harlem, and his reputation as the greatest trumpeter in Europe was known in America. African American newspapers had followed his every move for years, including his work with Coleman Hawkins, Django Reinhardt, and Josephine Baker. But he remembered the sting of American segregation, and he hated it. He chose to stay in Europe.

…..Briggs believed he could hide in his Montmartre apartment until the trouble passed, but the trouble did not pass. Hitler now controlled Austria, Czechoslovakia, Belgium, Poland, Luxembourg, and half of France. He installed puppet governments in Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, and the other half of France. He counted Italy as an ally, and his armies had penetrated so deep into the Soviet Union, they threatened to do what even Napoleon couldn’t do.

…..While the Nazis stored Europe and Russia, internment camps like Stalag 220 sprung up to house the prisoners, some held captive as forced labor, others as enemies of the state. As a black jazz musician and a citizen of a British colony, Briggs was an enemy twice.

…..To forget his fear and loneliness in captivity, he turned to the only thing the Nazis hadn’t taken from hm: music. Camp guards allowed the prisoners to form a makeshift orchestra, and Briggs led its brass section, honing it into a unit capable of tackling Beethoven, Strauss, and Mozart. He played to save himself but also to soothe the men’s souls, ending each concert with an old Negro work son. In a previous age, the song gave harbor amid the horrors of slavery; now it kept the cold ember of hope alive for Briggs and two thousand men amid the horrors of World War II. If the Nazis understood what the song meant to their wretched prisoners, the punishment for playing it surely would have been severe. Briggs played it anyway, blowing his life into the melody, while the lyrics rang in his bruised heart:

Don’t be sighing, little darling,

Sunshine follows after rain;

Though the shadows now are falling;

Better days will come again.

…..Then he climbed from the bandstand and walked to his hut, aching, shuddering, wondering, How did I get here?

-Travis Atria, from Better Days Will Come Again: The Life of Arthur Briggs, Jazz Genius of Harlem, Paris, and a Nazi Prison Camp (Chicago Review Press)

.

.

Listen to a 1933 recording of Arthur Briggs and pianist Freddy Johnson playing “Grabbin’ Blues”

.

JJM A few years back you wrote a biography of the rhythm and blues legend Curtis Mayfield, and now you have written a biography of Arthur Briggs, a jazz musician who lived in Harlem during the Renaissance, then in Europe in the aftermath of World War I, where he was among the first pioneers to introduce jazz music to the world. He became known as the Louis Armstrong of Paris. What inspired you to write a book about Arthur Briggs?

TA I was drawn to writing this book in a weird sort of way. While I was writing the book on Curtis Mayfield, I was in a bookstore and was taken in by a book called Americans in Paris, which was about Americans who had stayed in Paris after the Nazi occupation. For whatever reason it looked very cool, so I bought it. Toward the back of this book, three or four sentences were written about Arthur Briggs, and it gave me enough information to get me interested – a jazz trumpet player who spent four years in a Nazi prison camp, and while there he conducted a classical orchestra made up of fellow inmates. I thought that almost sounds like a movie to me. There wasn’t anything more about him in the book, and I just filed his story away in my mind.

After the Curtis Mayfield book came out, my agent asked if I had any other book ideas. I didn’t, but I told him that I was aware of this interesting story about a jazz trumpet player imprisoned during World War II. He was intrigued and told me he could sell that story. So, I started researching Arthur Briggs’ life, and the more I got into it, the more interesting he became. A friend of mine said that Briggs is kind of like Forrest Gump – he’s behind the scenes in so many huge moments of history, and was friends with or performed with famous people, yet few people had ever heard of him. Briggs is forgotten, and for whatever reason I am attracted to figures that have been forgotten.

JJM Your Mayfield biography was described by one critic as “thrilling,” and another called your book on Briggs a “nail biter.” What is your approach to writing biography?

TA I spent many years working for music magazines, especially Wax Poetics, which is a great magazine that focuses on the links between hip hop, R&B and soul music. So, this was really like writing an extended article. I’ve always wanted to write a book since I was a child. I came to writing the Curtis book sort of by accident. I had just gotten into his music and wanted to read a book about him but was shocked to discover a serious biography of him hadn’t been written. At the time I was about three or four years into writing about music, and chose Curtis as my entry into writing a book. Had I known how hard it was going to be I probably never would have attempted it, but I was just stupid enough to go for it.

Generally, I like to write about people whose lives have meaning. Curtis Mayfield was the premiere songwriter of the civil rights era – his music, in that sense, was very inspirational. Writing about Arthur Briggs was almost like writing a prequel to the Curtis book, right down to the fact that he was he was in Chicago around the time Curtis Mayfield’s grandmother moved to the city. And justice, race, humanity and courage are what both of their lives are about, so writing these books was more than just writing about the person, it was also about writing about the purpose of their lives in a way that could prove to be educational or inspirational to the reader.

JJM What were some of the primary sources you used for this book?

TA This book was often an excruciating process in terms of sources because Arthur Briggs did his most important work 100 years ago, and it was all done in Europe. I was living in New York at the time, so I just started off in the New York Public Library, going through all their databases and finding every mention I could possibly find of him in every possible newspaper and magazine. That research allowed me to create a basic timeline of his career up until the late 1930s or so. I then discovered that the Institute of Jazz Studies at Rutgers University had in their possession the only long interview Arthur Briggs ever did. For a long while that was the main source I had, and while I thought I had enough information to write the book, I didn’t have enough for it to be written in a way the subject deserved. I knew what he did and the people he knew and worked with, but it had no center because I didn’t know anything about him and what his life meant to him.

I felt it was important to find somebody who knew him, and after scouring the Internet I was able to find a woman whose father played with Arthur Briggs. I contacted her, and she told me she had known Arthur Briggs’ daughter, who she remembered used to live in Paris and who she had last seen there in the late 1990s. She had no contact information for her and wasn’t even sure she was still alive. I subsequently spent a long time looking for his daughter here, and at a certain point felt that I wouldn’t be able to find her without actually going to Paris. So, I went to Paris just hoping to find some way to find her, and figured that even if I don’t at least I can do some research there.

JJM Research in Paris is tough duty…

TA That’s right, what could be better! Getting information for this book was like a detective story. I discovered that Briggs is still fairly well known in Paris, where there is a big community of early jazz lovers that I connected with. It was one of those things where someone told me to talk to this guy, who led me to that guy, who told me to talk to this guy, who eventually introduced me to a lovely man who used to be Arthur Briggs’ next door neighbor. I spent the day with him – he even walked me through the cemetery to Briggs’ grave – and at the end of it I asked him if he happened to know his daughter. He did, and he gave me her address.

I knew she was reticent and had never agreed to speak with writers before, but I wrote her a letter on a wing-and-a-prayer. I wrote her a letter and walked to her apartment, leaving it behind with one of her neighbors who said they would deliver it to her. I stayed in Paris for a week or so more and never heard from her until six months later when, back in America, I received a message from her through her cousin James Briggs Murray, who used to be the curator of the jazz collection at the Schomburg Center in New York. He explained that Briggs’ daughter told him to check me out, which he did. He said that he enjoyed my biography of Curtis Mayfield and would like to introduce me to her in Paris. About a year later I went back to Paris, where I met with her and her family, and I found out that before Briggs died he recorded his oral memoir, which consisted of about 15 tapes of him describing his life story. This was like finding the Holy Grail! Up until this time I had spent about three-or-four years researching Arthur Briggs, and at many points during the process had despaired about having never learned anything worthwhile about him, but, all of a sudden I had this treasure trove of him telling his life story. So, that became the main resource for me because now I could write about not just what he did, but what it meant to him and how he felt about it.

I also found a diary in the Imperial War Museum in London that was kept by a man who was imprisoned with Briggs in the Nazi prison. This was important because the only thing Briggs didn’t talk about in his oral history was his experience in a Nazi prison camp, which, understandably, he didn’t really want to relive. But now I had that experience from somebody’s else’s perspective – a day-to-day chronicle of life in prison with Briggs.

JJM Briggs grew up in Grenada, where he lived until age 16, but there is little information about his childhood…

TA That’s right. Almost nothing.

JJM He didn’t talk about his childhood on his tapes?

TA No. When he first went to Europe he lied about his birthdate. The reason he lied is because he wanted to be in James Reese Europe’s Harlem Hellfighters, which was an Army regimental band in World War I, but he was technically too young to play in it. He stuck with this lie for the rest of his life. His memoir includes a pretty decent chunk of him just making up things about his childhood in South Carolina, which is unfortunate because he never told his daughter the true stories about his childhood – it is now impossible to get that.

JJM Briggs arrive in Harlem at the beginning of the Great Migration. Did he play a role in the Harlem Renaissance?

TA I wouldn’t say he played a role in terms of having an influence on it, but he was definitely a part of it in the sense that he was playing music in Harlem very successfully as a teenager, right at the outset of the Renaissance. So, he didn’t have a major role like a Langston Hughes did, but he was one of the unsung, unspoken people who were part of this burgeoning scene.

JJM Do you have an understanding about who he may have played with at that time?

TA His first experience playing there was in a church band that was connected to the school he was attending. At that time ragtime was still a new thing, and a lot of what he was playing were Sousa-like marches. At the same time he was also being introduced to people like Will Marion Cook, another guy that was hugely influential but who is now largely forgotten. I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that without Cook or without James Reese Europe the history of American music would be very different. Briggs was also in Chicago in 1918, watching Freddie Keppard and King Oliver and all these musicians who were the first geniuses of this new form of music, so he was connected to the mainspring of American jazz at a very young and impressionable age.

JJM You wrote that he went with Will Marion Cook to Lincoln Gardens to see Joe King Oliver…

TA Yes. He went with Cook and Mazie Mullins – a saxophone player who was one of the first women in jazz – because he was too young to get into the club by himself. Because this is so far in the past it is easy to see this as mostly stuffy old history, but this is a story about a teenager who had just lost his father, and he’s moved from the tiny island of Grenada to New York, where all of a sudden his mind is being blown by all these new sounds. That’s a perennial story. Yes, it’s jazz, and yes, this story is a century old, but when you put this history in a certain context, it’s easy to understand and appreciate.

JJM You tell many wonderful stories in the book, one of which is about his friendship with Sidney Bechet…

TA This is another instance where Arthur Briggs has that kind of Forrest Gump-like quality – he is in this huge, historic moment, but he is invisible within it. Sidney Bechet became a member of the Southern Syncopated Orchestra, which was Will Marion Cook’s group that Briggs was also a part of. When they went to Europe in 1919, Briggs was charged with being Bechet’s “babysitter,” because at that time Bechet was a very difficult man who liked to drink and fight, and who didn’t like to work. Throughout his life Arthur Briggs had the ability to charm some very difficult characters, and I think part of the reason he never became famous on his own is because he didn’t have a cutthroat instinct – instead he was a very gentle and decent person who was often passed over by people more unscrupulous than him.

For whatever reason, Bechet and Briggs became fast friends. Sidney was older than him and became an older brother or uncle figure even as Briggs was acting as the “babysitter.” So, this is another moment where he is getting a “lesson” from an absolute originator – while others in the band are playing ragtime or a version of light classical music, he is listening to Bechet playing jazz every night. This is the first time many of the Europeans had ever heard this kind of music, so a whole new world was opening for them.

JJM And, Briggs was there when Bechet bought his first soprano saxophone, another Forrest Gump moment…

TA Right. It’s an incredible piece of jazz history. Bechet and Briggs would remain friends the rest of their lives, and one of the more heartbreaking stories in the book is about how Briggs visited Bechet at his deathbed, and while there Bechet talks to Briggs about how much he’d love to eat a pear. So, Briggs leaves and goes all over the city looking for a pear but can’t find one. He goes back to the hospital the next day but by then Bechet had died. So, they had a very close friendship.

JJM How would you judge Briggs’ trumpet style versus his American contemporaries?

TA It’s interesting because he never quite became a visionary in the way Armstrong, Keppard or Oliver did. He was more like Red Nichols, who was somebody that he looked up to, and who was very technically proficient.

JJM And Briggs never became famous in America…

TA Right, and one of the reasons he never became more famous or well known in America is because he only stayed here for a couple of years. Even though the island of Grenada was a segregated place with its own terrible, painful racial history, he had never experienced anything like American segregation, and he truly hated it. So, once he went to Europe where it was comparatively free, he never really wanted to return to America. He only came back a couple times, and when he did he couldn’t take it here. Because of that he was cut off from the best jazz music that was being made – it was almost as if he sacrificed his career for his own dignity. The result is that he never really played with people who were better than him, which is how you get to be a better musician. Instead, he was always the guy who was dragging the Germans and the Europeans along, showing them how to play jazz. This ended up hurting his own playing a bit.

JJM So, he was soured on America and settled in Europe, and most enjoyed Paris. Why Paris?

TA For a variety of reasons there is a long, well-documented love affair between Black Americans and Paris, and even though Briggs was not an American, he fit into that scene. When he arrived in Paris it was the beginning of the vaunted “Jazz Age,” and at the time many Black American soldiers and musicians stayed in Paris after World War I, and a scene was beginning to grow there. He loved traveling Europe, but nowhere was it quite like Paris, and he felt free there like no other place before. Much of that had to do with the music that was being made and in hanging out with other musicians in all the little cafés in the city. It must have felt like heaven for a musician.

JJM And there was a lot of work for Black musicians at the time – so much work that some white musicians performed in blackface just to get work…

TA Yes. When jazz was still brand new, the music was almost incomprehensible to the European sensibility – but any random noise played by a bunch of people banging on instruments would be accepted as jazz as long as there were Black faces on the bandstand. In the middle of that is Briggs, who was a classically trained virtuoso whose goal from a very young age was to play music and improve. So, he could get all the work he wanted, but it took him several years before he could find the caliber of musicians he felt were worth playing with.

.

A musical interlude…Listen to Arthur Briggs’ Savoys Syncop’s Band play “Bugle Call Rag”

.

JJM When did he become a bandleader?

TA In the early 1920s he was playing with a band that had a residency at the Savoy Hotel in Brussels. The leader of the band at the time was a cutthroat guy who at some point left the band in the lurch. The members of the band discovered that he wasn’t paying them fairly, so the band basically broke up and reformed, this time with Briggs as the leader. That band was the Savoy’s Syncops Band, which became the longest standing band he led. They traveled all over the world and made a ton of recordings, including some of the earliest jazz recordings in Germany during the late 1920s. This is another example of Briggs being in Europe hurt him because he never got to experience the best available recording technology. Many of the recordings he made in the late 1920s don’t sound great because recording music was a brand new thing, and the gold standard for making a record at the time was being done in America, not Europe, but he couldn’t have resigned himself to being there.

JJM Earlier in the interview you compared Briggs to Forest Gump, as someone who participated in historic moments in jazz history. We already talked about his relationship with Sidney Bechet, and how he was with Bechet when he bought his first soprano saxophone. There are others he played and worked with that warrant discussion in this interview. For example, he had an interesting relationship with Josephine Baker…

TA Yes. Josephine Baker was the first Black female superstar and has long been a hero of mine, so it was great to write about her. I used her as a kind of subplot of this book because I felt like her life story mirrored some of the same themes as Arthur Briggs’, and they were doing it at the same time and in the same place. There were some uncanny, eerie coincidences, including the fact that as Arthur Briggs was preparing a concert in a Nazi prison camp for the Nazi commander of occupied France, Josephine Baker was preparing a concert to cover her tracks as a spy for the French Resistance.

She and Briggs knew each other and performed with each other, but Briggs didn’t like her, which was fascinating to learn. I think he was scandalized by her sexuality, and he also didn’t like the fact that he went on a tour with her in the late 1930s and didn’t get paid. She didn’t seem concerned by that, feeling that artists sometimes don’t get paid for their work, but he was upset because he told his musicians they’d be paid. This was all around the same scene, in the American singer and dancer Bricktop’s club in Paris…

JJM Where people like Cole Porter would hang out…

TA Yes, that’s right. The story involving Cole Porter at Chez Bricktop in Paris is one of my favorites in the book. At the time, Porter famously spent about half the year in Europe and often in Bricktop’s club, which was a mecca for jazz in Paris and where Briggs played in the house band. Porter had a table reserved there on a year-around basis – nobody else was allowed to sit at it, even if he wasn’t in Europe. One night he came into the club after having just finished writing “Night and Day” and wanted to hear the song performed, so he hands the sheet music to the band in which Briggs is performing, which they proceed to play. That song of course became a pillar of the Great American Songbook, and Briggs was part of the band who performed it for the very first time.

In the same club, the Prince of Wales – who eventually became King Edward VIII before abdicating the throne to marry Wallis Simpson – would hang out because he loved the new sound of jazz. He knew Briggs for a long time and actually heard the Southern Syncopated Orchestra perform at Buckingham Palace in 1919. The prince wasn’t a great drummer but he liked to play, and the band let him play because he would just throw money around to the musicians. So, while this relationship that would end up becoming so infamous was developing, the prince is in Chez Bricktop with Briggs, whose band is literally playing the soundtrack to this guy’s romance with a woman who will cause him to abdicate the throne.

JJM Going back to Josephine Baker for a second. She played with Briggs in Paris in April of 1935, which brought attention to Briggs in America. Some members of the press called him “another Louis Armstrong.” So, he had a legitimate shot at fame at that time but didn’t seem interested or motivated to take advantage of this opportunity. Why not?

TA Right, because he wasn’t interested in going back to America. There was actually this famous point in the 1930s when Armstrong busted his lip and was unable to make his dates, and the booking agent for those dates tried to get Arthur Briggs to fill in for him, but Briggs refused. The two of them were friends and actually hung out in Paris together while Armstrong was recuperating.

Briggs had a couple of opportunities to return to America, and it foreshadows probably the worst decision of his entire life. Even after he was warned to leave and go back to America because the Nazis were coming, he wouldn’t go. He didn’t want to go back to America. Also, at this point he was involved with a white Belgian woman, and he knew what the prospects for their relationship were in America – a Black man and a white woman, which was unheard of, probably even in New York City. So going back to America was a non-starter for him.

.

A musical interlude…Listen to the 1935 recording of Arthur Briggs (trumpet), Coleman Hawkins (saxophone), Django Reinhardt (guitar), Stephane Grappelli (piano) and Michel Warlop (violin) play “Avalon”

.

JJM Django Reinhardt is another fascinating story…

TA Yes, it really illustrates another good reason why Arthur Biggs remains in the background. Briggs was partially responsible for helping kickstart Django’s career. He was running a club in Paris, and Briggs gave Django’s string quartet he played in with Stephane Grappelli one of their first gigs, hiring them to play during intermission, which allowed them to hone their craft and work on something that hadn’t been done before – playing jazz without any horn or wind instruments. Briggs was also instrumental in helping them get recording contracts, as well as helping form the Hot Club of France, which ended up becoming the premiere vehicle for European jazz and perhaps the only jazz music produced in Europe that can stand next to anything done in America. Although Briggs was behind the Hot Club as one of its motivating, founding influences, he was completely cut out of the story. Like Sidney Bechet, nobody could get along with Django except for Briggs, who, for whatever reason, had that thing about him that allowed him to get along with just about anybody.

Around that same time Coleman Hawkins came to Europe and, if you’re going to come to Europe and play jazz you’re going to end up playing with Arthur Briggs – he’s the man in Paris and recognized throughout Europe as the best trumpet player there. So, the two of them made some fantastic recordings together, including some with Django. What makes it somewhat painful is that Briggs never did get to fully explore his musicianship with musicians of that caliber, because when you listen to the way he plays when he’s playing with Django, Grappelli, and Hawkins you can understand the level of his genius in the way you can’t hear when he plays with musicians who aren’t as good.

JJM You mentioned earlier about how he’d had chances to leave Europe but chose to stay. The journalist Robert Goffin, for example, recommended to Briggs that he leave Paris while he still could, before the Nazi invasion. He did apparently consider fleeing after the American consulate recommend that Americans leave Paris, but he chose to stay and was ultimately captured by the Nazis in October of 1940. Is there any evidence of the circumstances of his capture? Did he talk about that at all?

TA He talked about the period just before, but unfortunately he never talked about his actual capture, not even to his daughter. After he spent some time in one prison, he ended up getting transferred to the St. Denis prison camp. The only thing he really talked about was what they now call the Phoney War, when little actual conflict occurred, and which ended when the Nazis took Paris and about half of France. By that time it was clear that appeasing Hitler was not going to work, but World War II had not quite started yet. All the clubs Briggs used to play in were closed down at that time, so he had no work. This actually is another serendipitous thing in his biography because during this time a pianist friend of his, Tom Walton, invited Briggs to play with him at gigs that were available on the outskirts of Paris. Walton ends up being the musician who, later on, would petition for Briggs to come play with him at St. Denis, to be part of the orchestra there. Had that not happened he may not have survived the war because they could have sent him somewhere much worse…

JJM St. Denis was not an extermination or labor camp…

TA Right. In the lead-up to his capture all the work for musicians had dried up and he was just basically hiding in his apartment, only going outside to walk with the dog a musician friend left with him. During this time another musician friend – a white Frenchman who had been hiding at the front while the Nazis invaded– came to visit Briggs. He was all bloody and in a tattered uniform, and Briggs literally gave him his clothes to wear. The friend told Briggs he didn’t know how he could possibly make a living since he doesn’t have his instrument anymore, and Briggs gives him his trumpet. He figured he wouldn’t be needing his trumpet for a while, and he wanted to see his friend succeed. But, other than his daughter hearing a story about Briggs being accosted when he was out walking the dog, we don’t really know what happened.

photo German Federal Archives/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 3.0 DE

Otto von Stulpnagel (right), commander of Nazi occupied France

JJM Briggs eventually became the leader of the orchestra in St. Denis. One of the stories you tell is about how the Nazi commander of occupied France, Otto von Stulpnagel, ordered the musicians of the prison to perform a classical music concert, and wanted it ready in one month’s time. You wrote that “this was the hardest show Briggs ever played in his life.” It is hard to know, of course, the quality of the musicians Briggs had to work with, but that would have been a near impossible task even with great musicians. The repertoire was through-the-roof difficult…

TA Yes, unbelievable, including Beethoven’s “Fifth.” And it is interesting to wonder what the what the quality of the musician might have been. One of the few things Briggs did talk about his time in the camp was how he had to basically take the brass section under his wing, just drilling them in their pieces and in the performance, and he felt that after a while they got pretty good. He might have just been being nice to them, but I do think he believed they got to a point where it was respectable.

Other than Briggs and Tom Walton – the pianist who acted as the co-leader of the orchestra – they were the only professional musicians. But, because the concert was important to the Nazi commander of occupied France, the guards at St. Denis allowed them about four hours a day to practice and rehearse. So, even if the musicians were terrible, it allowed him to be himself each day. It was a lifeline for Briggs and was probably the only thing that kept him alive. And I imagine he would have expected a lot from those musicians – he wouldn’t have accepted mediocrity. He talks about how after they performed these pieces the orchestra received such thunderous applause that he was afraid the bleachers were going to collapse from the audience stomping their feet and yelling so hard. It must have been a pretty incredible concert. Imagine the challenges of playing Beethoven’s “Fifth,” Strauss’ “Radetzky March,” and Smetana’s “The Bartered Bride” in a Nazi prison camp on one of the coldest January’s of the 20th century.

JJM What were his some of his other musical duties at the camp?

TA He played reveille in the morning and put them to bed at night, and also accompanied any special announcement that was made. These duties probably allowed him some kind of special treatment; perhaps he received a little bit more food. I wrote in the book that it would have been worse for him had he been in a harsher prison environment than St. Denis., but while the Nazis liked to parade this camp before the Red Cross as some sort of prototype for how they treated prisoners, the truth of the matter is that even though the men there were not in an extermination or labor camp, they were nearly starved to death. They were still separated from their home, separated from any physical contact with women, eating nothing more than black bread with butter, and living in squalor with rats and lice for four years, three of which were the coldest winters of the 20th century.

JJM How awful…

TA Yes, it wasn’t a picnic. It wasn’t as if he was spending the war just hanging out, waiting for it to be over. He could have died at any point, not only from the harsh conditions, but also from the guards who were basically licensed to kill at will, especially toward the end of the war when many of the German soldiers were basically teenagers willing to shoot anyone who looked at them wrong to prove their manhood. It took incredible forbearance for Briggs to survive there.

JJM Wasn’t he offered a chance to play for the Nazi commanders?

TA Yes. He was given the opportunity to travel to Paris and perform in a club for the Nazis, but he refused.

JJM At the end of every concert, before leaving the bandstand, Briggs performed an old Negro work song called “Better Days Will Come Again.” How did Briggs come to know this song and why did he choose to play it?

TA Unfortunately, nobody really knows. His great nephew James Briggs Murray, who was a great help to me during the writing of this book, looked into this song quite a bit and discovered that it was a theme song of the Pullman train porters during the 1920s, about the time when Briggs would have just arrived in America. Being a porter was a popular job among Black Americans at the time, although they would work long hours for very small wages. And when they threatened to unionize, the Pullman Company came up with the idea to demand that each of their porters possess some sort of talent – either singing or playing an instrument. At that time “Better Days Will Come Again” became the theme song that the porters would have to perform on the trains, and it’s likely that at some point Briggs was on a train and heard the song. That’s the best we could determine. We aren’t certain why he chose it, or how he communicated the meaning of the song – if at all – to the other prisoners. We only have the stories of the aftermath of him performing it, and everybody standing up and saluting in a beautiful moment of protest, and the Nazis being confused about what was happening.

JJM Briggs had the reputation for being the best trumpeter in Europe. Was this known in America? Did American fans and other musicians know about him?

Arthur Briggs (bottom left) with his band in Egypt, ca 1937.

TA Yes, to some extent, because the Chicago Defender – which was the one of the biggest Black newspapers in America at the time – had a correspondent in Paris who was a huge Arthur Briggs fan. Every time he’d write a dispatch Arthur Briggs was mentioned, and since these Defender articles were syndicated, all the other smaller Black newspapers would also publish them. So, the word about Briggs must have got around. His recordings would have been the only way people in America could have heard him play, but I don’t know how widely available his records were, or, since he didn’t perform, even the size of his fan base here.

What is known is that musicians like Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Doc Cheatham, and Coleman Hawkins all knew of Briggs and were impressed by him, so much so that Armstrong and Ellington both tried to hire him. So, he was known where it counted. Whether or not he had a large popular following is unknown, but the people whose opinions mattered greatly respected him.

JJM What recordings of his would you recommend listeners seek out?

TA Many of his recordings can be streamed on Spotify and YouTube, and I would recommend that interested readers just do a search for his name and go through and listen to discover what you like, because there’s actually a big variety. Some of the late 1920s German recordings are very good, especially “Do the Black Bottom,” which he recorded with his own group. He also recorded with Marlene Dietrich, as well as with early German jazz bands, in which his role was basically as teacher.

The main influence Briggs had on jazz was not necessarily in his recordings but as being an ambassador for the music. He was basically teaching these German bands who really only knew “Oompa” music how to play jazz. When you listen to these recordings you can tell that the German musicians don’t quite get it, and Briggs’ trumpet is always the best part of the recording. But there are some things that he did with the Savoy Syncopators that are quite good, as are the recordings with Django, Stephane Grappelli, and Coleman Hawkins, which are jaw-dropping. They are the sort of performances that make you wonder how great he could have been had he been surrounded by the right people.

JJM What is Arthur Briggs’ legacy?

TA That’s a great question, and that’s ultimately the reason I wrote the book. I know that there’s a great deal of information in the book about a person no one knows much of anything about, and that’s a lot to ask of a reader. If there was a movie of his life, the meat of Briggs’ story would be of his World War II experiences, but you have to know the other aspects of his life to appreciate his personal journey and understand why he had the courage to act the way he did in that prison camp.

Arthur Briggs’ legacy is vital, and I had an experience that drove it home to me. While doing research for the book, I visited the St. Denis camp – the location is now an office building – and that evening on the Parisian television newscast was the story of the Charlottesville “Unite the Right” rally. So, that very day I had gone from the site of a Nazi prison camp to watching my own countrymen marching to the chant “Jews will not replace us.” That was a chilling moment. This is not 100 years in the past – this is today!

So, what is his legacy? It’s that he is a figure whose life is an example of what it means to have true courage in the face of evil, which is what his life was about in so many different ways. Whether it be the evil of American racism, whether it be the evil of European racism, whether it be the evil of Nazi-ism, his life was about retaining his dignity and refusing to let anyone take that from him, and for having the courage to make people see him as a human being.

The most important part of the book is his time at St. Denis, and the climax of that time is after the concert he performed at the behest of Otto von Stulpnagel, the German commander who was one of the highest-ranking officials in a war for white supremacy and who could have had Briggs killed with a snap of his fingers. At the end of the concert, because Stulpnagel was so impressed after seeing a Black man play Beethoven, he asked to meet Briggs. Briggs is brought before him and Stulpnagel tells him, in English, that he never would have believed that to be possible. Briggs responds, in German; “There’s a lot you don’t know.”

To me, that’s what his life was all about. The Germans may have had him freezing and starving to death in a prison camp, fearing for his life in the most undignified circumstances imaginable, but they did not take away his dignity, the thing that makes him human. There are several instances of that throughout his story, and I believe his legacy is to help pass on that kind of courage to people who are today attempting to stand up to things that seem invincible.

.

.

photo courtesy of Denis Pierrat/used by permission of the author

Arthur Briggs (far right), with Dizzy Gillespie and Charles Delaunay, 1950s

.

“[Briggs] was impulsive and quick to take offense, and he was known to abandon friends and break contracts with no warning when he felt his dignity was in question. But above all, Briggs refused to bend his principles to fit an unprincipled world. This set him on a difficult path, for those who do not ben often break. But he did not break. Though it never ceased to hurt and shock him when the world abused his ideals, he did not abandon them. He was the rare steadfast man.

“He was also the rare straightlaced man In a profession filled with drunks and addicts, Briggs was the soul of discretion. But beneath his conservative facade, he possessed an artist’s fire. This fire propelled him around the world, from Grenada, to Harlem, to Paris, to Cairo, to Constantinople. It drove him to make some of the greatest jazz records in Europe, and it saved his life in a Nazi prison.”

-Travis Atria

.

.

Listen to Arthur Briggs play “What a Difference a Day Makes” (with Michel Warlop and his orchestra, featuring Coleman Hawkins, Django Reinhardt, and Stephane Grappelli, 1937)

.

.

___

.

.

.

.

Praise for Better Days Will Come Again: The Life of Arthur Briggs, Jazz Genius of Harlem, Paris, and a Nazi Prison Camp

.

“If you’ve never heard of Arthur Briggs, join the club. After reading Travis Atria’s intensely readable, superbly researched account, you sure as hell won’t forget him. Atria has uncovered a largely untold, often harrowing tale of jazz, race, and international politics, and he has made it into a nail-biter.”

– Gary Giddins, author of Bing Crosby: Swinging on a Star and Celebrating Bird: The Triumph of Charlie Parker

.

“Arthur Briggs is a name you may not know now but will never forget after reading the details of his life. Music propels Briggs’s saga, and, for a Black man adrift in a white world, is eventually his means of survival — playing classical music in a Nazi prison camp, and teaching music in the years after World War II. Atria’s storytelling is intimately detailed and grandly epic, tragic and triumphant, living up to its title.”

-Ashley Kahn, author of A Love Supreme: The Story of John Coltrane’s Signature Album

.

.

___

.

.

Travis Atria is the author, with Todd Mayfield, of Traveling Soul: The Life of Curtis Mayfield. His work has appeared in Rolling Stone, Vanity Fair, Billboard, Wax Poetics, and other publications. He lives in Gainesville, Florida.

.

.

___

.

.

This interview took place on May 7, 2021, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician Editor/Publisher Joe Maita

.

.

If you enjoyed this conversation, you may want to read an interview with MIchael Dregni, author of Django: The Life and Music of a Gypsy Legend

.

.

.

Travis and Joe, Thank you for post! A book about his life is my next purchase! I can only imagine the challenges in compiling an authoritative story around his performing with Django and being captured by the Nazis.

I have long known about Arthur Briggs life and music. I immediately recall Mr Briggs was called the “British Louis Armstrong “.

My Grandpa Bob Effros was a jazz trumpeter and a British citizen by birth. He lived 1900-1983 mostly in New York and was/is my hero.

Now I’m going to have hit all my British Jazz Archives and articles to retrace whether Grandpa talked and possibly jammed w Briggs.

I was about to pull Michael Dregni’s book off my shelf – and I see you have an interview with him as well! Well you are just the cats ? meow….Am really appreciating your blog.. Joe