.

.

photo Nora Nicolini

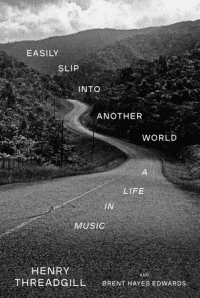

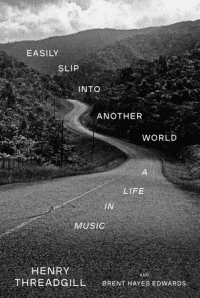

Henry Threadgill and Brent Hayes Edwards, co-authors of Threadgill’s autobiography, Easily Slip Into Another World: A Life in Music. [Knopf Publishing]

Threadgill is widely recognized as one of the most original and innovative voices in contemporary music, and the winner of the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for Music.

Edwards is the Peng Family Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University, and a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

.

.

___

.

.

…..A short list of great jazz autobiographies would include those by Louis Armstrong, Miles Davis, Hampton Hawes, Art Pepper, and Sidney Bechet. There are, of course, others.

…..Add this one to the list:

…..Easily Slip Into Another World: A Life in Music, by Henry Threadgill and Brent Hayes Edwards.

…..Threadgill is the celebrated composer, saxophonist and flautist who has been making music since the 1960’s in the various groups he’s led; among them Air, Very Very Circus, the Henry Threadgill Sextett, and Zooid. It was Threadgill’s 2016 recording with Zooid, In For a Penny, In For a Pound, for which he was awarded the Pulitzer Prize, one of only three jazz artists ever to do so (Wynton Marsalis and Ornette Coleman being the others).

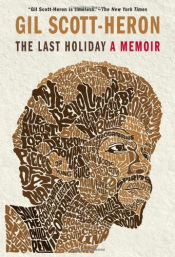

…..In a recent review in the New York Times, the critic Dwight Garner writes that Easily Slip Into Another World “is so good a music memoir, in the serious and obstinate manner of those by Miles Davis and Gil Scott-Heron, that it belongs on a high shelf alongside them.”

…..It only makes sense that a genius musician would write a genius autobiography.

…..The book takes readers on Threadgill’s incredible life journey; his childhood in Chicago, startling Vietnam war experiences (and their after-effects on his psyche, and on his music), interactions with the Chicago music scene of the mid-60’s (the time of the influential Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians which spawned artists and bands like the Art Ensemble of Chicago), his work in New York during the 70’s loft scene, and his extraordinary travel experiences.

…..As co-author of this book, the distinguished scholar Brent Hayes Edwards – a Guggenheim Fellow and Peng Family Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University – helped Threadgill tell his compelling story, one the pianist and Artistic Director for Jazz at the Kennedy Center Jason Moran calls “a profound gift [that] reminds us that composition is not just making music, but also shaping a life.”

….In my June 26, 2023 interview with Edwards, he talks about Threadgill and the book they set out to write that he ultimately hopes “might be able to merit a space on the shelf next to classics by artists such as Miles Davis and Gil Scott-Heron.”

.

Joe Maita

Editor/Publisher

.

.

___

.

.

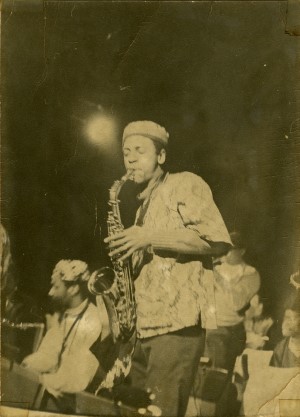

Courtesy of Henry Threadgill

.

.

“Music is something that takes you into a dreamworld. A world where sound is matter and what matters is sound: everything is communicated and digested and comprehended in that form and that form alone. Not translated or approximated into something you can see or smell or taste or say – your senses start and end with what you can hear.

“You have to enter that dreamworld in order to create music, as far as I’m concerned, with your neurosis in your side pocket. Your neurosis and your dream, they go hand in hand.”

-Henry Threadgill

.

.

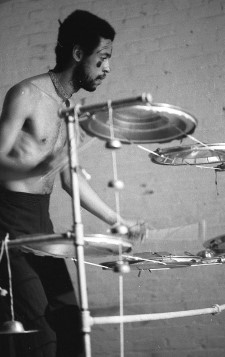

Listen to the 1980 performance of Henry Threadgill with his trio Air playing his composition “Be Ever Out,” with Threadgill, alto saxophone, flute, percussion; Fred Hopkins, bass; and Steve McCall, drums and percussion. [Black Saint/IIP-DDS]

.

JJM I’ve had an on-again, off-again, experience as a listener to Henry Threadgill’s music, so your book got me back into listening to it, and it helped me rediscover its qualities and depth. A recent review of your book in the New York Times said that Easily Slip Into Another World is “so good a music memoir, in the serious and obstinate manner of those by Miles Davis and Gil Scott-Heron, that it belongs on a high shelf alongside them.” So, congratulations on this achievement, Brent.

BHE Thank you, Joe.

JJM What enticed you to participate in this?

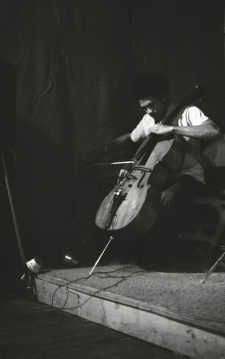

BHE It’s a long story. I suppose the first thing to say is that it didn’t start out as a book project. It started out as an interview. I met Henry in 2006 as I was starting research on a book about the history of the “loft jazz” scene in downtown Manhattan in the 1970s, a period when musicians including Ornette Coleman, Sam Rivers, Rashied Ali, Joe Lee Wilson, Juma Sultan, and Charles “Bobo” Shaw started presenting concerts in large, former industrial spaces in SoHo and the East Village. There is an allure to “loft jazz” due both to the volatility and daring of the music that emerged in these spaces and to its links to broader patterns of experimentation across the arts in the city at that time. But the scene remains hard to grasp precisely because the activity was taking place not in mainstream nightclubs but in these artist-controlled venues, which were often informal or underground. Like the other scholars who have begun to write the history of the period — Michael Heller, Stephen Farina, Rick Lopez, Ed Hazell, Cisco Bradley — I realized that there was no library to go to. The only way to do it was to talk to the musicians themselves, many of whom had meticulously kept archives of their own work.

Tom Marcello Webster, New York, USA, CC BY-SA 2.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Sam Rivers and Joe Daley at Studio Rivbea; New York, 1976

.

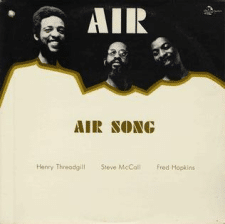

The cover of Air Song, the band’s 1975 debut (Threadgill, bassist Steve McCall, drummer Fred Hopkins are pictured left-to-right). The album was originally released on the Why Not record label in Japan, and later released in 1982 on India Navigation.

Henry was one of the first musicians I spoke to. I introduced myself to him after a workshop he was doing at the Jazz Gallery in its old location on Hudson Street in Tribeca, and we met a few weeks later to talk about his impressions of the downtown scene after he moved to New York in the winter of 1975-76. On a few occasions over the next couple of years I contacted him when I came across archival materials related to his work: for example, I met a photographer and filmmaker who had recorded what may have been the first concert in New York by the trio Air, with Henry, the bassist Fred Hopkins and the drummer Steve McCall, at La Mama Children’s Workshop Theatre in early 1976. I would give him copies of things, and we would talk some more about his memories of the scene.

Around 2009, Henry asked me to conduct a full oral history with him. He wanted an interlocutor to help him produce a detailed narrative of his entire career, from his upbringing in Chicago up to the present. At that point I had done a lot of interviewing but I hadn’t done a full-fledged oral history. But I was excited by the challenge, and in fact I ended up getting deeply involved in the field, co-founding a jazz oral history project through the Columbia Center for Oral History and working on a number of their other initiatives, including major projects on Robert Rauschenberg and on the Apollo Theater.

Henry Threadgill

.

photo Nora Nicolini

Brent Hayes Edwards

Oral history is dialogic and improvisatory — indeed, it shares a number of aspects with jazz performance itself — but it’s also an exercise in memory through a grappling with the historical record. So I did an enormous amount of research, not only listening to all of Henry’s albums but also constructing a detailed timeline of his career and consulting every shred of evidence I could find about his life and work, from his own collection of unreleased recordings, family photos, playbills, and flyers, to newspaper and magazine articles and books. That research gave me reference points and places to start: I could ask in an informed way about particular dates and events. But as we dove in, I realized that I had to be able to move in unexpected directions. Like any artist recounting his career, Henry would sometimes make connections between different periods, or bring up things that weren’t documented at all. Sometimes these were individual experiences, things no one else would know, like the stories from his time in Vietnam. Sometimes they involved prominent figures — Arthur Rubinstein, Phil Cohran, Duke Ellington, Cecil Taylor — but in fleeting encounters that left no trace aside from what Henry remembered.

We recorded hours and hours of the oral history, meeting regularly over the course of the following three years. I ended up with a transcript running hundreds of single-spaced pages. Even as I was gathering all this material, though, something shifted in our work: we started thinking about what we were doing as a book rather than an oral history. What’s odd is that I don’t recall us ever having an explicit discussion about it. There wasn’t a particular day when Henry asked me to help him write his autobiography. It felt more like a gradual revelation that that was where we were headed.

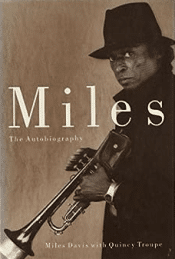

Miles: The Autobiography (with Quincy Troupe)

.

The Last Holiday: A Memoir, by Gil Scott-Heron

People who haven’t spent a lot of time reading oral histories might not realize how different they are from books. An oral history is a transcribed conversation: it’s a back-and-forth between two voices. And as a collaborative attempt to elicit memory through dialogue, it doesn’t always come out as a linear narrative. An oral history can meander or jump abruptly from moment to moment. The literary form of autobiography is an entirely different thing. So it was a big shift when we decided to try to write a book that might be able to merit a space on the shelf next to classics by artists such as Miles Davis and Gil Scott-Heron.

We didn’t throw out the oral history transcripts, of course. But they were only a starting point for what became the book manuscript. The organization of the book — above all its modular structure: the way each chapter is constructed as an interweaving of narrative threads — is something that only came out of the composition process. None of that is in the oral history. And Henry really left that part up to me. He would read the drafts and correct or add things, or tell me when something didn’t work for him. But he made it clear that it was my responsibility to figure out how to put it all together, how to make it into a book. So, from my perspective, it became a writerly challenge. I was no longer simply talking to Henry about his life and music. Now I was trying to find his “voice” on the page, and trying to orchestrate the narrative with something approaching the innovation and verve of his music.

JJM It’s a terrific story because it tells us much about who you are and the depth of your interest in the downtown “loft jazz” music scene, which is a history that should be told. The music coming out of that time and place was challenging for listeners and promoters of the music, and was created by fascinating, groundbreaking artists. It makes me curious to know what kind of music you grew up listening to that led you to finding Henry’s music so important?

BHE I’m not a performer, but I studied music for a number of years. I took lessons in piano, trombone, and conga, and in college at Yale I did the equivalent of a composition minor. So I had some musical training. I‘ve loved jazz since I first discovered it as a teenager in the 1980’s, but my taste in music is pretty eclectic. For my senior project in college, I composed a piece for prepared piano that was embarrassingly indebted to Cage’s Sonatas and Interludes. My composition teacher was an ethnomusicologist who specialized in Indonesian music, and for a couple of years I played in the Balinese gamelan he directed. At the same time, on weekends I was going to see all sorts of live music, both in New Haven and down in New York: from Cecil Taylor to David Murray, from Sun Ra to Etta James, from Sweet Honey in the Rock to Betty Carter to Fela Kuti. Not quite as eclectic as Henry’s early listening in Chicago, as he describes in the book, but maybe my idiosyncrasy prepared me somehow for his own extraordinary range.

Tom Marcello Webster, New York, USA, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Abdul Wadud at Studio Rivbea; New York, July, 1976

I think my interest in the music of the 1970s is rooted first of all in an attraction to the avant-garde, to modes of Black artistic experimentation and to their political implications. But it’s also an attraction to the period I missed: the music that came out just before I became a listener. Part of my fascination with the “loft jazz” scene is a New Yorker’s fascination with the New York I didn’t get to know, as someone who didn’t move here until the 1990s. It’s dangerous because it’s all too easy to romanticize the New York of the 1970s — the turmoil and edginess of the city during that time. But I do recognize that that’s part of the seduction for me. I’m also attracted to the ways that the downtown scene fostered all sorts of multimedia collaboration among dancers, poets, painters, photographers, and filmmakers. For a little while, the boundaries among artistic media were remarkably porous. This cross-fertilization is a central theme in Henry’s career, of course, going back to his collaborations with dancers and theater directors in Chicago.

JJM Henry’s music is complex, and not for everyone’s ears. How would you describe the experience of listening to it?

BHM There’s a compositional identity that runs through Henry’s music, but I also think of it as a constellation of sound worlds, to use the metaphor that runs through the book. It is hard to think of another musician — Mingus might be the closest parallel, or Miles with all his different periods — where the distance between each of his bands is so striking. For instance, there is a vast gulf between Henry’s great band of the 1980s, the Sextett, with its irresistible grooves and its contrapuntal interplay of bass, cello, saxophone, trombone and trumpet, and his next great band in the 1990s, Very Very Circus, with its unusual combination of two tubas and two electric guitars. That’s part of what I love about Henry’s music, that when you go from one band to the next — from Air, to X-75, to the Sextett, to the Windstring Ensemble, to the Society Situation Dance Band, to Very Very Circus, to Make a Move, to Zooid — it feels like you’re travelling among radically different sound worlds, or visiting multiple planets in a single galaxy. I love the way he describes his transitions from one ensemble to another in the book: he starts hearing different things, a new mix of sounds, and as a composer he has to find the right combination of instruments to capture what’s going on in his ears.

Even with all the differences among the ensembles, one thing that runs throughout Henry’s music is a capacity to be engaging — to draw you in as a listener — while also throwing you off-balance. Some of his earlier tunes with Air and the Sextett are based in relatively conventional forms and follow a familiar head/solo structure, but a lot of his music defies your expectations. Sometimes it’s a matter of timbre, as with the surprising conglomerate of multiple basses and flutes in X-75, and sometimes it’s a matter of structure, with things put together in unusual ways. I like that sensation of being thrown off-balance, of being rattled out of complacency. But that’s what can make Henry’s music difficult for some listeners who yearn for those familiar signposts or for the satisfaction of harmonic resolution. Henry’s music grabs you and takes you somewhere you didn’t realize you were going to go. That’s what I love about it. But you’ve got to be prepared to be “swept up” — to use one of Henry’s favorite verbs — to be surprised and spirited away.

.

A musical interlude…

Listen to the 1986 recording of the Henry Threadgill Sextett performing his composition, “Silver and Gold Baby, Silver and Gold,” with Threadgill (alto saxophone, tenor saxophone, bass flute); Rassul Siddik (trumpet); Frank Lacy (trombone); Diedre Murray (cello); Fred Hopkins (bass); Reggie Nicholson (percussion); and Pheeroan akLaff (percussion). [Legacy Recordings]

.

JJM Henry’s early musical influences included Charlie Parker, Sonny Rollins, Gene Ammons and John Coltrane. What was it about Parker that helped him form his view on music’s possibilities?

BHE As he explains in the book, for Henry and his friends Parker symbolized the dawn of possibility: the direction the music was heading next, and the excitement of modern experimentation. It’s important to remember that Henry didn’t start out as an alto saxophonist. His first love was the tenor, and so in terms of sound Ammons and Rollins were the major models.

JJM The book is subtitled “A Life in Music,” but it feels like multiple books within one…

BHE Yes, that’s fair to say. It is certainly a Vietnam memoir, not only because Henry’s stories about the war in those two chapters are riveting, but also because he makes it clear that his experience in the army was central to his development as a musician. It’s a Chicago book, as well, and an exposition of what I think of as the worldview of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), which was so pivotal in Henry’s development. At the same time it’s also a New York book. And you could also describe it as a travel narrative, since Henry emphasizes the importance of the time he’s spent abroad, not only in Southeast Asia but also in the Netherlands, Italy, Venezuela, Trinidad, and India, to his musical sensibility.

Air – Steve McCall, Henry Threadgill and Fred Hopkins; San Francisco, 1979

At the end of the day, I think for Henry the book is first and foremost the autobiography of a composer. He is a player and he has performed with all sorts of ensembles, as he recounts, but the main thrust is his development as a composer of his own music. So even if it can be called a jazz autobiography, the book isn’t only meant to stand on the shelf next to books by Miles Davis or Charles Mingus or Sidney Bechet. Henry was always thinking about his own trajectory in relation to the paths of Stravinsky, Varèse, Hindemith, Copland, and Glass, too. The book claims that term, rightfully, for Henry, and by implication for black composers across the board. And so Easily Slip into Another World is very much the story of the making of a contemporary composer in the broadest sense of that term, without worrying so much about supposed generic distinctions between so-called “jazz” and “classical” music. Henry’s career demonstrates just how inadequate, just how confining those sorts of pigeonholes can be. Of course this to me is also very much a protocol that comes out of the AACM: it’s not just about “jazz” but about “creative music,” a much more capacious category.

JJM Henry’s life experiences shaped his music, which is certainly not unique to him, but as readers will discover, his experiences are unique and often extraordinary. At the core of the book is his Vietnam war experience, which includes a story about how his arrangement of a song while serving stateside was considered so blasphemous by the archbishop that it led to his deployment to Vietnam. It is like no story I have ever heard before. Can you talk about that a bit?

BHE Henry volunteered for the army in his professional capacity as a musician. If you were an established professional in a given field, whether you were a cook or an ophthalmologist or a car mechanic, you could offer your services in your area of expertise, rather than waiting to be drafted as an infantryman. Henry was stationed at Fort Riley in Kansas, where he eventually became the head arranger for the top band. It was a relatively cushy set-up until Henry did an experimental arrangement of patriotic classics like “America the Beautiful” and “My Country Tis of Thee” for a big military function. His irreverent medley offended the powers that be so much that they summarily shipped him off to Vietnam — or at least that was what he concluded, since no one ever told him why he was suddenly reassigned.

Courtesy of Henry Threadgill

Henry Threadgill, with Ray Heckman and the French horn player referred to as “Dirty Red,” at the 4th Infantry base camp

Despite his shock and disorientation at the way it happened, and despite the trauma and terror of Vietnam, Henry also explains that his war experience was formative for him as an artist. I think if he hadn’t heard the gongs played by the Montagnards — the indigenous musicians in the hills of Vietnam — he might not have been inspired to invent the hubkaphone, the percussion instrument made out of hubcaps that he plays so memorably with Air. More broadly, Henry says that the experience of war — the particular auditory sensitivity that is a product of being in a situation of mortal danger in an unfamiliar environment — shaped his hearing, and in that sense became an integral part of his makeup as a composer and player. It wasn’t something he chose, but it made him who he became.

One of the book launch events we did in June was a conversation between Henry and the poet Yusef Komunyakaa, who is the other African American Vietnam veteran who has been awarded the Pulitzer Prize, Yusef for poetry in 1994 and Henry for music in 2016. They knew of each other’s work, but they’d never had a conversation before, and it was an intense dialogue. They didn’t know each other and they weren’t in the same place in Vietnam, but there was this palpable resonance between their experiences, especially in the way they described the impact of the war on them as young black men and as artists. It was a remarkable conversation to witness.

JJM There are a couple of examples in the book of the ways the things Henry went through in Vietnam stuck with him even after he got back. I’m thinking of the startling passage where he fantasizes at length about a revenge murder of a young man who had threatened him and his pregnant wife with a pistol while they were out for a walk in Chicago. These are very powerful experiences to share…

BHE Yes, and it demonstrates that many of the young men who didn’t choose to be in the war were transformed in a way that the country never really dealt with. As Henry says, an entire generation of young men who fought in that war and survived it came home severely damaged. Even if they weren’t injured, many of them found themselves unable to take on regular jobs or to maintain healthy family relationships. And their problems were dismissed or ignored; if anything, veterans were seen as villains, the embodiment of an unjust and unpopular war. Although the Vietnam chapters are harrowing, I think the opening of Chapter Five is one of the most powerful sections of the book, because it captures the aftermath of the war: what it was like to come back and try to reintegrate into “normal” life.

JJM How did his war experience and the sounds he heard while in Vietnam inform his musical sensibility?

BHE It’s a complicated question because obviously his music is not simply an attempt to capture or recreate the soundscape of Vietnam and what he heard over there. It’s not like any of his music sounds like a war environment. It’s more about its effect on his hearing. “It’s like I grew a set of antennae over there,” he says at one point. “When I returned, my reception equipment was different.” Maybe you could say that his penchant for throwing listeners off-balance has something to do with an atmosphere where you’re constantly on edge, constantly listening for signs of danger. But I think the main point is that the war made him hear differently. It’s about the shaping of his aural sensitivity rather than about some particular sound he hears while he’s there.

Although I do think the book suggests that the war played a crucial role in forming his musical sensibility, it’s also important to remember that there are all sorts of other influences as well. Henry talks about the impact of all the different kinds of music he played in the 1960s and 1970s: not only in AACM bands, but also in evangelical church services, in blues bands, in parades, in Latin and polka groups. So his aesthetic as a composer comes out of the mix of all those sources. And it’s a unique individual concoction. A number of Henry’s contemporaries in the AACM, including Joseph Jarman and Lester Bowie, also had war experiences that might be said to have shaped their musical sensibility, but Henry’s music doesn’t sound like Jarman’s or Bowie’s music.

JJM His work with the evangelical preacher Horace Sheppard in the mid-1960s was fascinating on a lot of levels. It was when he began playing alto, for one, but also because his participation in this troupe caused him to miss out on being a part of the creation of the AACM…

BHE Yes, when the AACM was founded in 1965, Henry was touring with Sheppard. He was close friends and schoolmates with Jarman and Roscoe Mitchell and Anthony Braxton, but Henry moved away from that world for a couple of years when he was working with Sheppard. His involvement in the AACM didn’t really commence until 1968 when he returned from Vietnam.

JJM In addition to being a musician, Henry was an inventor of instruments, notably, as you mentioned earlier, the hubkaphone, which was made of hubcaps. I couldn’t help but think of Harry Partch, the composer and inventor of unique musical instruments. What compelled Henry to create the hubkaphone?

BHE Henry does mention Harry Partch in passing, because once while Air was touring in the Southwest they went to a dance studio where Henry was able to see some of Partch’s invented instruments. But Henry had already invented the hubkaphone by that point. He describes his motivation more as an attempt to recreate something of the sound of the Montagnard gongs he’d heard in Vietnam. And clearly it’s also related to the broader AACM fascination with “little instruments” and invented devices of various sorts, perhaps most famously in the work of the Art Ensemble of Chicago.

Courtesy of Jacki Ochs

Threadgill playing the hubkaphone for a performance at Roberta Garrison’s dance studio on Crosby Street in New York in the late 1970’s

I’d also say that Henry is a bit of a tinkerer. He likes to fool around with stuff and see what he can come up with — in the book there is a hilarious section about his ill-fated attempts to mix homemade magic potions and to build a flying machine when he was a kid in Chicago. To me, there’s a joking, mad scientist aspect to the way he puts things together, whether one is thinking of the timbres and rhythms he combines, or of objects like the hubkaphone or its larger cousin the hubkawall. At the same time, along with the playfulness and what you might call the junkyard aesthetic of it, there’s also something serious and innovative about the way he repurposes these found hubcaps to approximate the effect of those Vietnamese gongs in a way that ends up being something entirely new.

JJM The sound of paint brushes helped inspire his approach to playing the instrument….

BHE Yes. The Surinamese painter Jan Telting actually painted a portrait of Henry. Telting is an extraordinary figure who spent time in the United States in the 1960s and had ties to the avant-garde jazz scene. He was close to the saxophonist John Tchicai, who wrote a tune called “Quintus T.” about Telting that was recorded by the New York Art Quartet. Through an unlikely series of events, Henry and Telting met in Amsterdam during the months Henry spent in the Netherlands in 1971 performing with Leonard Jones and Wadada Leo Smith. Telting let Henry stay in his studio for a while, and Henry explains that watching Telting paint had a major impact on Henry’s own performance style, especially on the hubkaphone.

There’s a wonderful scene in the book where Henry describes watching Telting paint while standing on a sort of dolly. In other words, he wouldn’t simply stand in front of the canvas; instead he would step onto this platform on wheels and move it around, painting from different sides and at different angles, almost as if he were dancing. Henry figured out a technique for the hubkaphone by doing something similar, choreographing the way he would move as he played it.

It’s an anecdote that gives a sense of the ways Henry can find inspiration in all sorts of sources all around him, whether it’s a painter at work or a great novel or hubcaps for sale in a street market. It’s an incredible outlook to have as an artist: you learn new approaches to your own work by extrapolating from things in other forms, without trying to replicate them directly.

JJM He is deeply inspired by the visual. In the book he writes about being able to hear music in the sight of a tree branch hanging outside his window…

BHE Yes, that passage came out of one of our oral history sessions, when Henry had a composer’s residency at the Aaron Copland House in Cortlandt Manor, up the Hudson a couple of hours from New York City. I would drive up to visit him and we’d talk for hours. One day we spent a long time talking about this plant outside the window. He explained that inspiration could come from anywhere, even from looking at a vine on the side of the house morning after morning, observing the gradual changes.

JJM Well, there is a lot poetry in that, and poets can get similarly inspired…

BHE Yes.

JJM Henry left Chicago in the mid-1970s for New York, where there was a new and bigger audience for his music, and more funding opportunities as well. One of the people he played with there was the pianist Cecil Taylor. How did this experience impact the way he thought about his own bands, and his own music?

BHE He played with Cecil briefly at the beginning of the 1980s. It only lasted about six months, and unfortunately that iteration of the Cecil Taylor Unit was never recorded. But Henry describes the experience as being important for him, even if most listeners don’t know about it.

In the book, Henry is eloquent about insisting that his music can’t be reduced to his discography. His art is much broader than the things he’s had the chance to document on record. And in a live setting, in the heat of performance, what happens both for the musician and for the audience is something else entirely — something that can’t ultimately be captured or transmitted accurately by an LP or a CD.

Rehearsing and performing with Cecil turned out to be transformative even if it was a fleeting affiliation. Henry says that Cecil’s modular approach to composition and improvisation forced him to rethink his own approach, in ways he tried to incorporate on his own subsequent records like the Air LP Air Mail. It also made him think about bandleading in a different way: Cecil had strategies of keeping his musicians on their toes that Henry says he adapted with some of his own ensembles later.

JJM Henry won the Pulitzer Prize in 2016 for his recording In for a Penny, In for a Pound. He was only the third jazz composer to be so honored — Wynton Marsalis and Ornette Coleman being the others. The recording, according to the Pulitzer committee, is “the latest installment in saxophonist/flutist/composer Henry Threadgill’s ongoing exploration of his singular system for integrating composition with group improvisation.” How did Henry react to the news of this great honor?

BHE He was definitely surprised. As he recounts it, his record company submitted the album for consideration, and I don’t think they even told him that it was up for a Pulitzer. So the prize wasn’t on his mind at all as a possibility. Once he got over the initial shock, he was flattered by the recognition, of course, although it’s not the only major award he’s won: he was named an NEA Jazz Master in 2021 and has won a Guggenheim and a Doris Duke Award, among other things.

It’s been interesting to observe the evolution of the Pulitzer Prize for Music in the years since Henry won. Since 2016 it’s gone to a number of other Black composers, including Rhiannon Giddens, Tania León, Anthony Davis, and Kendrick Lamar. Considering the brilliance and diversity of their output, categories like “jazz composer” don’t feel particularly relevant. Maybe we’ve finally reached a point where the excellence and impact of music is no longer being judged in terms of shopworn generic expectations.

JJM And he keeps going…

BHE Yes. As he declares in the book, Henry is always focused on the next thing. He isn’t interested in repeating what he was doing ten years ago — or even last month! Henry is adamantly forward-facing. He’s always scheming up the next move, the next collaboration, the next project. The sound that’s hovering right around the corner. That’s what he’s constantly listening for. To quote the title of the famous Ornette Coleman record: Tomorrow Is the Question!

.

photos by Giovanni Piesco/2008

“You can’t stop time. There is a momentum in the molecular structure of things. You can’t prevent change from happening. You can only try to figure out how to ride with it.”

-Henry Threadgill

.

Click here to be taken to a page where you can listen to the opening number from In for a Penny, In for a Pound, the 2016 winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Music [Pi Recordings]

Click here to be taken to a page where you can listen to “Beneath the Bottom,” from Zooid’s 2021 album Poof [Pi Recordings]

Click here to be taken to a playlist curated by Brent Hayes Edwards that serves as an excellent introduction to the music of Henry Threadgill

.

.

Easily Slip Into Another World: A Life in Music

by Henry Threadgill and Brent Hayes Edwards

[Knopf Publishing]

.

.

___

.

.

About the authors

The composer and multi-instrumentalist Henry Threadgill is widely recognized as one of the most original and innovative voices in contemporary music. A Chicago native, he studied at the American Conservatory of Music and, after serving in Vietnam, joined the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM). He has performed on more than thirty albums, including acclaimed releases from his bands Air, X075, the Henry Threadgill Sextett, Very Very Circus, Make a Move, Zooid, and Ensemble Double Up. His awards include a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2003, a United States Artists Fellowship in 2008, a 2016 Doris Duke Artist Award, and a 2016 Excellence in the Arts Award from the Vietnam Veterans of America. Threadgill was name a Jazz Master by the National Endowment for the Arts in 2021. His four-movement work, In for a Penny, In for a Pound, received the Pulitzer Prize for Music in 2016. (henrythreadgill.com)

.

Brent Hayes Edwards is the Peng Family Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University, where he is also affiliated with the Center for Jazz Studies. His books include The Practice of Diaspora: Literature, Translation, and the Rise of Black Internationalism (2003) and Epistrophies: Jazz and the Literary Imagination (2017). He was a Guggenheim Fellow in 2015, and in 2020 he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

.

.

___

.

.

Praise for the book

.

“Vividly told, alternately uproarious and devastating, Easily Slip into Another World serves up astonishing tales of Threadgill’s life in Chicago, Vietnam, New York, and on the road, punctuated by deep revelations about the Black experience, American empire, an artist’s life, and the entire history of music. Threadgill and Edwards have crafted an invaluable literary experience: a real-life Bildungsroman, plainspoken, erudite, and searingly honest. This book will be savored and cherished for generations.”

—Vijay Iyer, Composer and Pianist; Rosenblatt Professor of the Arts, Harvard University

.

“The personal, the political, the musical, the spiritual: all merge in this brilliant, beguiling memoir by one of the major musical minds of our time. Easily Slip into Another World not only documents a radically inventive individual talent but also celebrates a singularly vital collaborative community — that of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians. It shows the indivisibility of what comes from within and what comes from without: making music as a way of being in the world.”

—Alex Ross, music critic, The New Yorker, and author of The Rest Is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century

.

“Easily Slip into Another World is the vibrant autobiography of Henry Threadgill, a fearless explorer whose music and performance transcends categories and genres. His encompassing vision and adventurous spirit of inquiry have influenced generations of composers and musicians. This book is an affirmation of the power of creativity to change our world and discover new ones.”

–Meredith Monk, Composer, Singer, Director/Choreographer

.

“The same passion and joy that Henry Threadgill brings to his life is manifested in his perpetual quest for the right sound, the right composition, the right combination and collaboration. Anybody with a spark of creativity in any part of their lives should take inspiration in his unrelenting commitment to experimentation as the spirit that drives us to revelation. After reading this book, full of insight and humor and even a tiger passing in the night, I suggest you turn on some of Threadgill’s music and do as he says: listen.”

—Viet Thanh Nguyen, Pulitzer prize-winning author of The Sympathizer

.

“I frequently call Henry Threadgill my favorite living composer not only because of the webs of sound he spins, but also because he is the best storyteller I know. This book is a profound gift: it reminds us that composition is not just making music, but also shaping a life.”

—Jason Moran, Composer and Pianist, Artistic Director for Jazz at the Kennedy Center

.

“Without question Easily Slip into Another World will be one of those books we talk about, read, and re-read for years to come – a new classic autobiography, building upon and upending the tradition of the genre at the same time. It is breathtaking.”

—Farah Jasmine Griffin, Ransford Professor of English and Comparative Literature and African-American Studies, Columbia University

.

.

___

.

.

This interview took place on June 26, 2023, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita

.

.

Click here to subscribe to the Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter (it’s free)

Click here to help support the continuing publication of Jerry Jazz Musician, and to keep it commercial and ad-free (thank you!)

Click here to read other interviews published on Jerry Jazz Musician

.

___

.

Jerry Jazz Musician…human produced (and AI-free) since 1999

.

.

.