photo by Herman Leonard

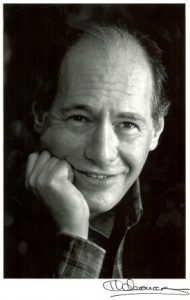

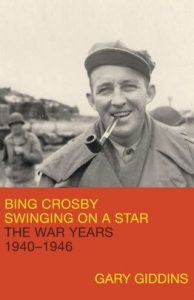

Gary Giddins,

author of

Bing Crosby: Swinging on a Star: The War Years, 1940 – 1946

_________

Few Americans have lived a life so momentous as Bing Crosby’s. His enormous popularity spread across virtually every entertainment medium in existence during his time, particularly during the 1940’s, America’s most consequential 20th Century era.

He was Hollywood’s #1 star, often as romantic lead, at times as charming comic, and, eventually, as the symbol of the country’s moral compass. As an ingenious radio entertainer, he broke long standing racial, genre and programming boundaries, ultimately leading to a change in the way broadcasts are produced. His enduring recordings — among the best-selling of all time — were made during the complex era of a strike and a recording ban. His interest and investment in technology led to recording techniques still in use today.

While his importance as a performer during the 1940’s is well established, perhaps his biggest impact was as an “American.” His was a unifying voice for the overall war effort through his tireless, critical work as entertainer of Allied troops overseas, and on the home front, where his countless USO tours and selfless personal appearances raised millions of dollars in war bonds. He was America’s “everyman” who, like Will Rogers before him, was emblematic of the successful, “good” man.

In the second volume of his biography of Crosby, Swinging on a Star: The War Years, 1940 – 1946 (Little, Brown and Company), Gary Giddins, National Book Critics Circle award-winning writer/biographer who for thirty years wrote the “Weather Bird” jazz column in the Village Voice, expertly chronicles Crosby’s life and times from over 300 interviews he conducted for this book, as well as the use of previously unknown letters and other resource materials. The result is an ambitious, elegant, and superb study of American cultural and societal history with its most popular entertainer of the time at its centerpiece, written by a revered film critic, the most eminent jazz writer of his generation, and, in the opinion of the Wall Street Journal, “the best thing to happen to Bing Crosby since Bob Hope.”

The following interview with Mr. Giddins about his book — hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician publisher Joe Maita — was conducted on September 24, 2018.

_________

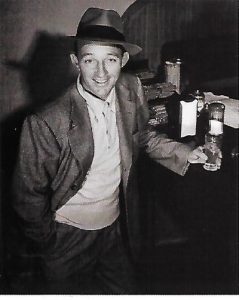

photo HLC Properties, Ltd.

Bing Crosby, c. 1940

“[The 1940’s] would be the decade he most fully inhabited. He would explore the delicious motley of pop music more deftly and comprehensively than anyone else and in the process become an essential voice of the home front. Whatever frustration, boredom, or despair he experienced he kept hidden. Even as he contemplated familial and professional ruptures, the public could see only the steadfast strength and reliability in countless magazine and newspaper stories. His discontents aside, idleness was never an option for the man whose persona hinged on the pretense of laziness — who walked, talked, sang, and acted as if tranquility represented moral certainty, the virtue of the unflappable. He was about to do his bit in ways he could scarcely imagine, mirroring and defining the times more astutely than he and all but a few men and women had ever done.”

– Gary Giddins

Listen to “Swinging on a Star”

_________

JJM The promotional letter from your publisher announcing the publication of your book starts with four words: “The wait is over.” It has been 17 years since the publication of Pocketful of Dreams. You have had a lot of interested readers anticipating this volume, haven’t you?

GG I hope so. I’d like to tell you I spent each of those 17 years locked in a room with the ghost of Der Bingle. But one must make a living. In the interim I published four other books, including a jazz textbook that’s been through a few editions with a new one coming out next year, as well as hundreds of articles, and I taught for several years, including five wonderful years directing the Leon Levy Center for Biography at the CUNY Graduate Center. Still, Crosby was never far from my mind, and I found that patience landed me several interviews previously denied me and much material that turned up in and out of public archives. Biographies have a way of dictating their own timelines. I expect some Crosby fans may be frustrated that Swinging on a Star doesn’t cover the entire second half of his life, but I hope they’ll give it a chance and that the singularity of the story and the way it’s told will earn an audience beyond devoted Bing lovers. This is the book I most wanted to write and Little, Brown allowed me to do so without any compromise, for which I am very grateful.

JJM How much new resource material did you find between the publication of the first volume — A Pocketful of Dreams — and this book?

GG So much that it changed my trajectory. The main thing that happened after the first volume came out is that Mrs. Crosby, who had ignored my entreaties in the years it took me to research A Pocketful of Dreams, liked it. She generously invited me to the Crosby home for several days, permitting me to pore over his files, letters, photographs, Dictabelt recordings, the transcripts for Call Me Lucky, quite literally thousands of documents that I transcribed or photocopied. Crosby was something of a pack rat, which is marvelous for a biographer, as is having the confidence of his widow. More materials were later found in a storage locker and as those were inventoried by Robert Bader of Crosby Enterprises, my research assistant in Los Angeles would regularly visit Robert’s office, copy stacks of documents and send them to me. Inevitably, you read through a great deal of dross to find the gems, but the gems proved illuminating and, on several occasions, revelatory. They gave me access to Crosby’s own voice — personal letters, contracts, business dealings — and a perspective far more candid than the one biographers usually construct from public documents and interviews. I read correspondence that, in some if not most instances, had not been read by anyone other than the original recipients.

JJM So, having access to all this new material influenced your decision to limit Swinging on a Star to the years 1940 – 1946…

GG Of course. These are the central years of his career, and I always knew they would occupy most of the second volume. But this new material made me want to write a book exclusively about Crosby and the war years, a story set against the home front, which he helped define and which certainly helped to define him.

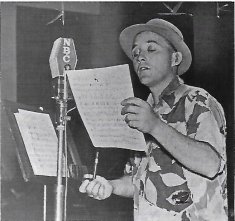

photo HLC Properties, Ltd.

Crosby at a Kraft Music Hall rehearsal

There is an early chapter in the book called “Prewar Air War” in which he secretly goes to see the head of Kraft Foods to acknowledge his weariness and dissatisfaction. That was the first time I encountered Crosby in a slump, a period of irresolution — a new side of him, despite the hundreds of interviews I had done. We know he revolutionized radio after the war, changing a live medium into a recorded one, but his earlier rebellion against the status quo underscored for me a thematic circularity, which is to say that at the outset of the war, he was troubled by some of the same things that occupied him at the end: the tribulations of his marriage, the domesticity imposed by weekly radio, the need to revise his cinematic persona.

The book opens with him asking his wife Dixie for a divorce, a request he soon rescinded, and ends with him alone on a train returning to her after an absence of four months, two spent on his ranch in Elko, Nevada, and two in New York, where he made several significant recordings, conducted a romance, and took his stand against what he considered the tyranny of broadcasting. In a sense, despite the upheaval of war, he ends as he began, and yet the war transformed him profoundly. It occurred to me that, no matter how rich or powerful, we are all prisoners of situations we accept or create. In Crosby’s case it was his marriage, Catholicism. his professional obligations. I got hooked on circularity — the old commodius vicus of recirculation — as a means of disciplining the narrative.

JJM And all of this was in the face of the view Americans had of him. It was assumed he lived this idyllic life…

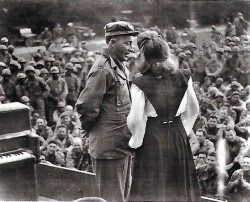

GG In many respects he did, of course, but the fact that he was troubled and that he had doubts was not something he wanted anyone to know. Even more surprising to me than his ennui in the year preceding Pearl Harbor was the extraordinary amount of work he did in support of the war effort. He traveled some 50,000 miles in those years and made his first trip overseas two months after D-Day, performing in pretty sticky situations. Yet few people beyond the troops themselves knew how really close he was to the front. Kathryn Crosby told me she teared up when she read some of the letters from soldiers who wrote to thank him. So did I. The voices of these men stick in your head. I’m especially proud of the chapter on France.

Crosby entertaining thousands of fliers the day after visiting children who barely survived the Freckleton disaster

*

“It was a strenuous assignment, and I know that it must have been tiring for you at times. Yet you showed untiring zeal and unflagging good humor throughout the tour, and your spirit was an example to the people who saw and heard you. I should like you to know that your work for us in September has been a real contribution toward the winning of the war and that all of us at the Treasury are deeply grateful.”

-U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau

*

photo HLC Properties, Ltd.

Crosby with Dinah Shore in Chalons, France

*

“I can never forget my amazement at seeing young men snatched out of civilian life, many of them irresponsible, pleasure-seeking youngsters, thrown into the most rugged assignment in the world and delivering and doing a great job, applying seriousness and ability to the fearsome task which is war.”

-Bing Crosby

___

Listen to “I’ll Be Seeing You”

But the sheer number of shows he did at training camps in this country is astonishing and much of it was unpublicized, unreported, like the time a general in Southern California asked if he could drop by on Christmas to entertain his men, or when he sang a cappella in a hospital in northern England for the four six-year-olds who barely survived the Freckleton disaster, a tragedy so awful that Churchill ordered the press not to report it for fear of devastating national morale.

It is incredible to me how little has been written about the war from the perspective of the USO. Even Crosby passes over it with hardly a mention in his memoir or postwar interviews. As he repeatedly said to the men he performed for, he didn’t want to be thanked for it; he was there to thank them for risking their lives. And he was indefatigable. Several reporters who covered his more formalized tours described him as heroic, and I don’t think that’s an exaggeration. The trove of letters he received were not only from men in uniform, but from parents, wives, siblings, and friends of soldiers who were killed. They felt a need to share their grief with Crosby, to bless him and thank him. Richard Holmes, the British biographer, whose work I venerate, remarked that passages in the book about soldiers listening to “White Christmas” in rapt silence, looking tearfully at their shoes, offered him a new way to look at Americans in the war. I had a hard time limiting the number of letters reprinted in the book. They preserve a sense of what Bing’s presence meant in those years, when the nation found in him a unifying force that no other performer, other than FDR, possessed.

JJM You wrote that Crosby “had more influence on the millions of families routinely huddled around their radios than anyone other than F.D.R.”

GG Well, he represented something fine about the country that we may have forgotten. We have huge celebrities today but is there anyone you would describe as being beloved, as Crosby was during this period, and indeed over the better part of his 50-year career? In the earlier book, I write about the deliberateness with which he underscored his ethnicity, his “Irishness,” during the interim before Pearl Harbor, in direct contrast to the demagoguery of Father Coughlin.

Bing provided a voice of decency and reason, yet he wasn’t the least bit sentimental — that is one of his great strengths and one of the things I most admire about him. He is sincere, not mawkish. There is about him an aloofness, a quietly powerful stability that his audience clung to. I quote a line from a character in W.R. Burnett’s novel High Sierra to that effect. He never got tiresome and he never got pious. The cultural critic Gilbert Seldes, who wrote beautifully about Bing, emphasized the fact that his audience hadn’t tired of him after all those years when he dominated recordings. He remained real, reliable, straightforward. After Japan surrendered, he went on the air and as others read scripture and puffed themselves up with platitudes, Bing simply said, “What can you say at a time like this, except thank God it’s over?” At the same time, it exacted a terrific toll on him and his family. Nothing is free, everybody pays, as the narrator says in Leo Hurwitz’s great 1948 documentary, Strange Victory. Yet, for those of us who grew up with the horrific, divisive home fronts of Vietnam or Iraq, there is something almost cleansing about the one Crosby helped to sustain.

JJM The very concept of the home front is a critical part of the book…

GG In biography, as in criticism, context is essential. No one lives in a vacuum of art or work or family. Crosby in the war years is inextricable from the war, from the preparation and fighting, from the fears and losses, from the massive changes in technology, with their sidebar feuds, like the ASCAP strike, which inadvertently launched countless new songwriters working in idioms like country & western and rhythm & blues, or Petrillo’s recording ban, which backfired in that it ended the dominance of bands and the rise of singers.

In 1942, when Archibald MacLeish, the poet, became Director of War Information, he said the principal battleground of the war was not Europe or the South Pacific, but American opinion. Eisenhower agreed, calling the home front “a strategic place,” where the country had to possess a will for victory. Yet among the thousands of World War II books, little attention is focused on the home front after Pearl Harbor frees FDR’s hand. I try to track the shadow of the war throughout the book as counterpoint to Crosby’s story. The first chapter cuts between his private woes and the cultural and political terrain of the period between the invasion of Poland and Pearl Harbor. That terrain maps the route he would traverse as an artist and as a man.

JJM He was compared to Will Rogers as a symbol of the good man…

GG I cite a number of people who compared him to Will Rogers. We hardly remember Rogers today, but he was widely read and quoted, his movies were hugely successful, and his early death greatly mourned. He represented the public wit as a totem of common sense, standing above the petty bickering. Not surprisingly, David Butler — who had directed some of Rogers’s best-known films — thought that only Crosby could play him in a bio-pic. Paramount and Warner had a tussle over it, so it never happened, although Crosby certainly wanted to do it and even did a screentest that you can find on youtube. In the late ‘40s, Crosby remade one of Rogers’ most famous films, A Connecticut Yankee.

I suppose the point here is that people were looking back to see who Crosby was comparable to, but at that point he stood out as an irreplaceable original. No one had ruled so many aspects of American entertainment as thoroughly as he did for two decades. He arrived at the beginning of a new technology, electrical recording and talking pictures. After the war Bing was prominent in the transition to tape, which he helped to finance. He was a creature of technology who lost his taste for performing live. Yet during the war he did so constantly, to entertain troops or sell war bonds. In 1945 the armed forces magazine Yank polled returning servicemen on who had done the most for morale. Crosby topped the list, ahead of FDR, Eisenhower, everyone. But the very qualities that endeared him to so many people during the Depression and the war, the aloofness, the quiet charm, the easygoing illusion of lazy indifference, dated him. In the jet age styled by the renewed Sinatra and the juggernaut of rock, Crosby’s imperturbable cool, what I describe as “the virtue of the unflappable,” seemed grandfatherly and irrelevant.

JJM You wrote, “Marriage was not the only Crosby battleground. Pervasive dissatisfaction roiled him at thirty-seven, as he reckoned his achievements and the restraints they put on him. After a fifteen-year ascent from the fringes of vaudeville to the peak of Paramount’s mountain, he felt cramped by the very successes he had struggled to attain.” What did he want at the outset of the 1940s?

GG Well, that’s the question. What did he want? I don’t think he knew, or, as I write at one point, he knew what he wanted now, but not if he would want the same thing tomorrow.

*

*

*

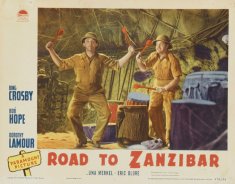

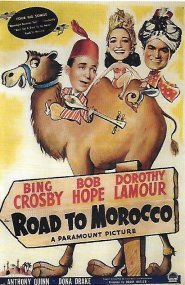

photo HLC Properties, Ltd.

Dona Drake, Bob Hope, Bing Crosby in Road to Morocco (1942)

___

View a clip from Road to Morocco

It’s important to remember that by the late 1930’s his career began to wane a bit. He hadn’t had a big record in a while, and though he made a memorable movie in 1938 called Sing You Sinners, he didn’t have as much success in 1939. Then, in 1940, teaming up with Bob Hope, who he had not seen since 1933, he had the surprisingly huge hit The Road to Singapore, which repositioned him as a comic foil, and not just the amusing romantic lead he had been in so many of the earlier films. He satirized that character. At this point he and Paramount have to be asking, where does a career like this go? The Road films with Hope create an ideal contrast to his solo pictures: the former are irreverent, madcap, fast, funny; the latter are built around emotional pivots, defining his character as a man fleeing fame and responsibility — three of them have him yearning to hide away in remote inns, a reflection of his dissatisfaction with fame.

The war turned him around, revived his energy, handed him a mission, creating a new demand for him beyond anything he had experienced. It enabled him to recognize his talent and fame as implements, benign weapons of war that boosted morale and raised many millions of dollars. He felt younger, more energetic, excited about what he could achieve. He so enjoyed getting laughs that on one of their tours, Phil Silvers had to remind him to sing. The press made a big thing of his touring without his movie wig, the scalp doily, as he called it. This was a part of his resolve to appear as himself, a regular guy with a remarkable voice, and not as a Hollywood invention. His wig maker told me that another of his clients, John Wayne, would rather have been shot than be caught bald. Crosby thought it phony to don a toupee to entertain men who risked everything. The two activities he loved most were singing and golf. The fact that he and Hope could go out on a golf course, followed by thousands of spectators, to raise money, singing on the ninth hole and auctioning his tie or his clubs, then go from Army camp to Army camp performing for the most appreciative audiences in the world was a highlight of his life.

JJM In 1941, due to the ASCAP strike, Crosby was recording public domain songs like “Nell and I,” “The Old Oaken Bucket” “Old Black Joe” and “Mary’s Got a Grand Old Name.” What was the effect on his career as a result of having to sing these songs?

GG There wasn’t much of an effect — most of the bad songs didn’t sell and were soon forgotten. Before then, Decca’s Jack Kapp had already repositioned Crosby from the Prohibition-era jazz hipster and heartthrob balladeer to an all-purpose interpreter of Americana, acknowledging few stylistic borders. He could handle 19th century songs that his rivals wouldn’t touch with a pole and interpret them with tremendous feeling.

I focus on a few of them, like “Beautiful Dreamer,” which the critic Otis Ferguson thought was the way Stephen Foster would have wanted to hear it. Another example, and one of my favorite Crosby recordings, is “The Sweetheart of Sigma Chi,” an impossibly sentimental frat song from early in the century, which he turns into a remarkably powerful performance, a de facto art song.

As I’ve said, the ASCAP strike, which was stupid and unnecessary, launched something great in the formation of BMI as a major competitor to ASCAP, uncovering countless new songwriters, mostly from the South. One of the first country songs Crosby recorded was by Cindy Walker, a teenager whose career he launched. She became a major figure in country music — Willie Nelson recorded an album of her songs, crediting her as an inspiration. Crosby also helped the career of Louis Jordan by recording a couple of duets with him and establishing “Is You Is or Is You Ain’t My Baby” as a mainstream hit; another record, “Pistol Packin’ Mama,” made with the Andrews Sisters, that I would put on my short list of Crosby’s great recordings. So, this was a crucial moment in American music, kicking off a transformation from songs created for Broadway and movies to songs that reflected local, often rural, tastes that became part of the national fare. His influence was decisive because he embraced every idiom as though he were born to it.

JJM His radio show was unique in the diversity of performers he had as guests…

GG There was nothing else like it then or ever. The number of opera singers he had, the number of classical musicians. We have a remote control, but in those days, people sat close to the radio and reached out to twirl the knob if they were the least bit bored. So, how do you make people listen to classical music in great numbers? He made it fun — he would have somebody come on and play a short, serious piece on cello, and then have the same musician duet with him on a pop song. He didn’t make it pretentious, didn’t oversell it, didn’t present classical music or jazz as if they were musical vitamins that would make you a better person. He made it all fun. Among jazz musicians, he presented Armstrong, of course, and Art Tatum, Wingy Manone; Ellington was a regular guest, and so was Ella Fitzgerald, whom he revered. He was one of the first to champion Nat Cole, when he was still known as a dazzling pianist. At the same time, he had singers like Paul Robeson and, as regular cast members, Connee Boswell, Mary Martin, Peggy Lee, Judy Garland, and the Charioteers, a Gospel-based R&B vocal group that injected tremendous energy into the show.

JJM You wrote that the scene in which Crosby’s Holiday Inn character, Jim Hardy, tries out his latest creation “White Christmas” as a “transitional moment for the Crosby persona.” How so?

GG Even film buffs have forgotten Crosby’s 1930’s films, in part because Universal hasn’t done much to make them available. They aren’t among TMC’s holdings. But he had played a range of characters far different from the ones that emerged during the war. In The Big Broadcast, which made him a film star, he plays an alcoholic. In Sing You Sinners he gambles away his family’s savings and makes a pass at his brother’s fiancé. Several of these characters are neither amiable nor admirable, although they usually undergo a transformation, and we remain sympathetic to them.

But in Holiday Inn, though he is remote, devious, and obstinate, he emerges as somebody very solid, a figure of quiet strength and accountability. Even though the screenplay of Holiday Inn is filled with betrayals as he and Fred Astaire compete for the Marjorie Reynolds character, the film is in effect a transitional vehicle leading to the Leo McCarey films, where he becomes solid-as-a-rock, an Uber mensch, a miracle worker who remains, paradoxically, very understated, average, and non-judgmental. Filmgoers are often surprised that the mother in Bells of St. Mary’s is a sympathetically characterized prostitute. Yet, as Mary Gordon observed in her essay on Father O’Malley, he doesn’t attempt to convince her to try another profession nor does he condescend to her. The Production Code Administration’s Joe Breen protested this setup, but McCarey held firm. I doubt he could have prevailed with any actor other than Crosby.

JJM You called the character that he played a “fantasy priest — a perfect, albeit celibate, man…Liberated from romance, venality, and vainglory but not from intrigue and statecraft, Father O’Malley emerged as a superhuman fount of liberal wisdom, empathy, and action. As emblematic of the war years as Atticus Finch was to the civil rights era, O’Malley represented a righteousness people could feel and believe in.” There had to have been risk in him taking on this role…

From Going My Way (1944), Crosby (as Father O’Malley) with Barry Fitzgerald

___

View the trailer for Going My Way

GG The risks were tremendous in the view of Paramount. Leo McCarey said that an executive asked him how much of his own money he had invested and offered to repay him and add a hefty bonus if he would cease production on Going My Way. They were afraid not only that the film would tank — they figured nobody would want to see the crooner as a priest — but that it would permanently diminish his value as a star. McCarey first offered the film to RKO, which rejected it outright on the assumption that Crosby would be ridiculed, and Catholics would be up in arms. After Going My Way opened to sensational reviews and broke box office records all around the country, they continued to underestimate its appeal, which greatly increased with the return of millions of servicemen and the even greater success of Bells of St. Mary’s. Crosby and McCarey realized that the turned-around collar was a perfect disguise, increasing the power of Crosby’s persona, emphasizing a masculine security at once safe and beguiling. He never liked playing a lover on screen anyway. From the moment he appears, white collar and straw boater, asking for directions to the strangely spectral church, he is relaxed, amusing, confident, and in charge. It’s a wonderfully graceful performance.

JJM How did his role as Father O’Malley create complexity in his real life?

From Bells of St. Mary’s (1945), Crosby as Father O’Malley and Ingrid Bergman as Sister Mary Benedict

*

“If divorce were to enter your life it would be an incalculable blow to so awfully many people and would, I am afraid, do incalculable harm to countless souls. It is part of the price of the position to which you have risen that the actions of your private life become of vast significance to the millions who look up to you.”

-Frank Corkery, Gonzaga University president, 1945

___

View the trailer for Bells of St. Mary’s

GG I suppose people expected him to be perfect. When he had his affair with the actress Joan Caufield, he went to see Cardinal Spelman, who told him you are Father O’Malley and Father O’Malley cannot be divorced. The role gave him gravity as an actor, though to his credit he took risks in subsequent roles, playing alcoholics, a cruel father, and a serial killer. After his death, he became an irresistible target of people gleefully charging that he wasn’t really a saint, a claim he never made and that his films and memoirs certainly don’t make. You know, everything that was said about Crosby was said about Henry Fonda, only worse, but fans shrugged it off. Fonda was a brilliant actor who did not have to measure up to Father O’Malley. The same with Sinatra, who was always considered to be dark and edgy, so whatever he did was chalked up as “Sinatra being Sinatra.” For that matter, no one went to see The Miracle of the Bells, in which Frank takes his turn as a priest.

JJM His role as a husband and father has always been a disturbing part of his biography…

GG Not “always.” It is mostly posthumous, because in 1953, when he published Call Me Lucky and wrote of spanking and using a studded strap on his kids, the reviews singled out what an exemplary father he was.

.

Crosby with sons Gary, Dennis, Phillip, Lindsay

*

“He was away a lot on location. Sometimes we didn’t see him for months. But when he was home, it was like my whole world was there. He was tremendously sensitive and he cared deeply. He just had a rough time showing it.”

-Gary Crosby

___

Listen to “I Want My Mama”

A no-nonsense disciplinarian, practically an antidote to a new style of parenting represented by Dr. Spock. It was Crosby himself who blew the whistle on himself and a kind of parenting he came to regret. When he had a second chance with his new family, he was very different with those kids, who speak of him proudly and lovingly. He realized he had made some terrible mistakes with the four boys — his strictness, his discipline, corporal punishment, absenteeism, and unreasonable expectations. He tried to make it up to them, but after he married Kathryn Grant, he focused on his second family, taking it with him everywhere, drafting them as performers in his shows. I pull no punches depicting the darkness of his first marriage and some passages are excruciating to read, but there are nuances and complexities to be considered. Every unhappy family is its own tragedy.

JJM His wife Dixie was a complex figure, and as I was reading this book I couldn’t help but feel sympathetic toward her. She clearly had alcohol issues, but she was alone all the time, raising four boys…

GG I think you’d have to have a heart of stone not to be moved by Dixie’s plight. I’ve become very fond of Dixie, as indeed practically everyone who knew her was. You see her at her best in Pocketful of Dreams, before the problems take their toll. In Swinging on a Star, she is drinking heavily at the start and it contributes to her early death. No one, not her friends, doctors, or Bing, knew how to help her. She continued to show moments of great charm and wit.

She was one of the few people in Bing’s life who could stand up to him and match him line for line with spirit and humor. But the marriage reeled out of control during the 1940’s. Crosby was away for long spells, sometimes weeks and months, while she was confronted with raising growing boys that she did not know how to handle. Much of their upbringing was delegated to housekeepers and governesses — some of whom were more brutal than Bing or Dixie. Gary tells about one of them who submerged the kids in a bathtub. Luckily, Dixie happened to walk in and kicked her out of the house.

JJM Crosby demanded a divorce in 1941, at which time she promised to stop drinking, but Crosby insisted that she prove it. It is all really sad, but you couldn’t blame him for making the choices that he made professionally, especially as they relate to how he felt he was needed to support the country during the war…

GG I don’t blame anyone. I try to tell a story as best I can understand it with the material at hand. The reader can decide if he or she wants to don black robes. I would hope not. It is quite true, as you say, that his war work was of immense importance, and it gave him the option of leaving a troubled house. Dixie did not have that option. Her drinking and her reclusiveness were attempts to handle a difficult situation. But at times she rises above it and I treasure those little victories.

JJM At the end of 1941, Crosby and Dixie owed $164,000 in federal taxes and $41,000 in state taxes. Was this enough of a burden that may have influenced career choices?

GG I don’t think so, beyond properly insuring himself. He turned down much more lucrative deals to go with other radio sponsors and recording companies. He insisted on making a couple of independent films, despite accurate warnings of doom from his lawyer and accountant.

He continued to breed and train horses and bet on them. He certainly became smarter about business as he got older, and he was always paid well, extravagantly compared to most film stars, but I do not think money was ever his primary interest. At the close of the war, he was impatient to divest himself of his stake in Del Mar, but that’s because he wanted to move into baseball, in part as an example to his sons. I don’t see any evidence that he rescinded his request for a divorce to please his tax man, who didn’t give him the bad tax news until after he heard that Bing had changed his mind. The big change in his financial situation was brought about after the war when he engaged a man named Basil Grillo to oversee his holdings and investments. Grillo revived Bing Crosby Productions — which became hugely successful with such 1960’s television series as Ben Casey and Hogan’s Heroes.

His royalties were pretty amazing. One of the most surprising figures in the book, to my mind, concerns the annual royalties at Decca, which inclines Jack Kapp to tear up his contract and, as Bing stands in silence, replaces it with a far more generous one. Crosby’s royalties for that year exceeded a quarter of a million dollars on records at a time when only two other Decca artists exceeded $34,000. Remember that his career continued for half a century, and even after he fell out of favor, his records were fail-safe annuities. Even now, of the three biggest selling singles of all time, two are Crosby’s “White Christmas” and “Silent Night.”

JJM A common thread throughout the book is that people had difficulty getting to know him. As an example of this, you wrote, “After the death of Bing’s touring partner the great guitarist Eddie Lang in 1933, no one got too close; no one got all of him.” Phil Harris, a particularly frequent companion after the war, told an outsider who remarked on their reputed intimacy, “If I knew Bing better than anyone, no one knew him.” Did Lang’s death have a lifelong impact on Bing?

GG Eddie Lang’s death was something he never spoke or wrote about. He was his accompanist, traveling companion, and confidante. His wife Kitty was a devoted friend to Dixie and Bing and plays a significant role in Swinging on a Star. I doubt anyone ever got as close to Bing as Eddie.

I think Bing felt partly responsible for his death, a great musician lost at the age of 30. At Bing’s insistence, Eddie appeared on screen backing him in The Big Broadcast and Bing argued for him to have a speaking role in his next film College Humor, a kind of sidekick role. But Eddie had a problem with his voice, he was chronically hoarse. Bing encouraged him to have a tonsillectomy, which went horribly wrong. As I show in the source notes, information made available after the publication of Pocketful of Dreams confirmed Kitty’s suspicion that he died unnecessarily owing to medical incompetence. At the funeral, Bing was mobbed, pews overturned. He was horrified. When I spoke to Phil Harris, I said everyone says you knew him better than anyone, and that’s when he made that remark. Incidentally, I hope readers won’t ignore the source notes. There are some terrific stories and asides buried there, which would have impeded the narrative, but were too good not to include.

JJM You write how Bing was a man of great discipline in everything from his preparation for recording sessions and performances to being punctual…

GG There is a refrain in the book of musicians, arrangers, directors who refer to sessions called for, say, 8 AM. They get there at 7:45 and Bing is waiting, reading a newspaper, anxious to start, because when the gig is done he has an appointment for 18 holes and is going to split no matter what. Gary Crosby said that when the surgeon general went on TV and announced that smoking will kill you, Bing quit. Gary said, “Can you imagine what it’s like to live with a man who has that kind of discipline?”

I’ve had medical people tell me that Bing couldn’t have been an alcoholic because he remained a social drinker all his life. But the evidence, which includes blackouts and long binges, suggests that he had been. During the Depression he frequently drank himself into insensibility. Yet after he turned his life around, he was able to have a cocktail or two at a party or dinner and not get sidetracked or fall off the wagon. There is only one time in the book where Crosby gets soused and Kapp has to cancel a recording session, of “Ave Maria.” Blake Edwards told me he arrived on set once with a hangover when they were shooting High Time and was so charming about it that you couldn’t be mad at him. Incidents like that are rare after 1932. I think discipline informs his approach to singing and acting.

Crosby with James Cagney during the Victory Caravan, 1943

*

“Few people outside of the theatrical profession realize what a tremendous task it is for an entertainer, accustomed only to a motion picture set, a recording studio, or a small broadcasting studio, to get up on a stage and face 10,000 sober faces staring at you from out of the darkness.”

– Bing Crosby

___

Listen to “Don’t Fence Me In” (with the Andrews Sisters)

James Cagney captured this beautifully when he describes a performance during the Victory Caravan, where the audience greets Crosby in thunderous rapture, and his performance kills, an impossible act to follow. Then Cagney notices Crosby’s leg is slightly shaking and realizes that all of that insouciance, his nerveless confidence, is part of his very hard work. Artie Shaw once said that Bing was no more Bing than Bogart was Bogart, meaning they created their characters for public consumption. In Crosby’s case, he and the characterization do meet. I’ve heard tapes of him sitting around at home with friends telling stories and jokes and it’s the same Crosby you know from radio and film — fast, witty, relaxed, comfortable in his own skin. On the other hand, he hated people who gushed. If you came over to him and with the light of love in your eyes it made him nervous. Just as Hemingway liked to hunt with non-writers, Bing prized friendships with golfers, horsemen, and fishing partners who could have cared less that he was a film star and didn’t own a single Crosby recording.JJM Toward the end of your book is this almost bizarre relationship with the Barsa sisters, two young women who were basically stalking him, yet he embraced them, to the point of having them visit his ranch in Elko…

GG Almost? I love the Barsas. It’s one of my favorite episodes and it fit perfectly with the theme of circularity I spoke of. Violet Barsa honored me with her trust, initially making the diary and other materials available piecemeal and ultimately photocopying it all. After she passed on, her daughter Pam — who was Bing’s goddaughter — visited our home with a trunk full of scrapbooks and letters.

Mary and Violet Barsa

*

Pamela Crosby Brown Collection

Crosby with Mary Barsa on his Elko, Nevada ranch, 1950 There are two things about the Barsas that readers respond to with a kind of shock: first, that these young women are clearly stalking him, as though this was a mere eccentricity that fans did once upon a time, even to the examination of his hotel trash; and second, that he invites them up to his hotel room. Yet he is so above board, treating them like young adults with respect and a genuine interest in their lives. He was not interested in them as fans. It turned out to be a lifelong association, and for me, as a biographer, that diary was a gift from heaven, an amateur surveillance with the ring of truth. I’m a stickler for corroboration, and the diary never failed in its accuracy and observational detail. There is one passage of them describing Bing waiting in the snow outside the Waldorf for a cab to take him to Grand Central. He doesn’t have somebody getting him a cab, he doesn’t have a driver waiting, he’s just there, waiting like any other guest. He has to wait for a while until he gets a cab and loads his luggage. Then the sisters start running in the snow to the station, which is a few blocks from the Waldorf. When they get there, Bing is aboard the train and they don’t see him again for a couple of years. But that image of him alone on the Twentieth Century, making that long, long journey back to L.A., back to the family, and capped by the card that he sent to them at Christmas, signed “Dixie, Bing and the boys,” was a natural ending. I couldn’t improve on it and didn’t try.

JJM You were critical of much of Crosby’s post WWII recordings, for example, writing that on many of them his voice was “often arid and hollow. The upper mordents flutter effortlessly, but the phrasing is mechanical and the repertory is maddening.” Given your 25-year connection to his work as Crosby’s biographer, do you ever find it difficult to be critical of Crosby?

GG No, not at all. I don’t have an investment in painting him in a particular way, and if you cannot recognize a bad performance, how can you be certain of acclaiming a good one? I am fascinated by the way Crosby’s singing differs, in certain periods, between what he does on the radio and in the recording studio or on prerecords for a film. Sometimes, his voice is just burned out and you delight when he rests it for a few months and returns with his best burnished tones. I mentioned the “Ave Maria” session where he walks in juiced to the gills, with a hole in his pants, clearly thinking about something else because after the session he is going to see Joan Caulfield, and Jack Kapp tells him that he is not going to get this today, we’ll do this some other time. A few months later, Bing returns to the studio and kicks “Ave Maria” way into the grandstand, an extraordinary performance, dramatic and lustrous.

You don’t need 25 years to know good music from bad. Critical objectivity extends equally, however, to the facts of his life, and that’s where the investment in time pays off. You trust your research, you sift for facts, you refrain from glib speculation and mind-reading, you find that sheer persistence will open doors, and a single letter or memo can incline you to reexamine or dismiss a supposition. When I started on Crosby, I was inclined to believe a lot of the terrible things I had read about him. My proposal focused on the idea of a performer who personifies warmth to his public but is cold to his intimates. I started to do interviews and people gave me a different sense of him. Nabokov spoke of inventing Europe, Russia, and America in his fiction. A biographer is confronted with the challenge of inventing a life through language, turning a timeline of facts into a narrative. Crosby was not a saint, and I never wanted to write about a saint. He was a good and valuable man and I enjoyed the time I spent with him. He wasn’t a perfect artist, but when he rose to the occasion, he was a great one.

JJM How has this experience of being Crosby’s biographer impacted you?

GG It changed my life. I’m a middle-class Jew and a child of the 1960’s who loves jazz more than anything in the world and did not expect to devote a third of my life to a working-class Catholic pop singer whose celebrity began to fade shortly after I was born. Except for his jazz recordings with Bix or Louis, I hardly knew Bing. “White Christmas” meant nothing to me, and I rolled my eyes at Going My Way, until I attended a screening at Lincoln Center and found how funny and resonant it is. I had to be talked into doing Crosby, having rejected the project for years. But the more I looked into it the more I was attracted to the subject, which after all allowed me to write about music and film, my twin obsessions as a critic, and the more surprises I uncovered about him: his tolerance and racial liberality, his innovative use of technology, the hidden treasures in his filmography, the diversity of his radio work, the brilliance of his recordings, the admirable aspects of his obstinacy, his influence on the course of three networks, the tireless devotion of his work for the armed forces during the war, the modesty that allowed so much of his achievement to be forgotten, not least the remarkable 1944 tour in England and France.

JJM You write quite a bit about race…

The Life magazine article reporting on the June, 1943 race riot in Detroit

*

Judy Schmid Collection

*

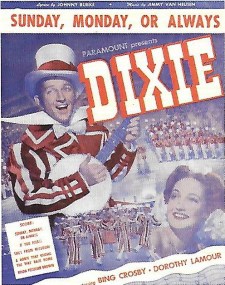

View the Dixie trailer

*

Listen to “Abraham” from Holiday Inn

GG Chapter 13 mostly, though it’s a theme that runs throughout the book. I discuss blackface minstrelsy in the context of his film Dixie, a fictional but interesting portrait of Dam Emmett. Speaking of surprises, I knew that miscegenation laws lasted longer in the United States than in the Third Reich, but it had never occurred to me that blackface had a tremendous revival at the very moment we are battling dictatorships touting racial exceptionalism. In the source notes, I offer a list of some 60 films that encouraged Americans to think of minstrelsy as an amusing instance of cultural heritage. In one issue of Life magazine, it ran an account of the bloody race riot in Detroit, where whites were attempting to keep blacks out of affordable housing, and its cheerful plug for Dixie, which captures minstrelsy at its most grotesque, and no one saw irony in the juxtaposition.Incredibly, the peak of minstrelsy came after the war, in 1949 when Jolson Sings Again was the number one picture at the box office, with Pinky, about a woman passing for white, in second place. I wanted to explore the paradox of Crosby, who did much to advance the opportunities for black entertainers, hanging on to his affection for blacking-up, an affection that began in childhood when he saw Jolson perform in Spokane. Here’s a guy who opened doors for integrated performances, who championed so many great black artists from Ethel Waters, Louis, and Paul Robeson to Ella and Nat, who broke a color bar by appearing on the AFRS radio show Jubilee, when it had been exclusively black, and gave the Charioteers a permanent place on Kraft Music Hall. Yet he appeared in blackface in three 1940’s films — and was widely cheered for it! Most newspaper movie reviewers, and for a while Irving Berlin himself, thought that the big hit in Holiday Inn would be “Abraham,” the faux-spiritual done in blackface, rather than “White Christmas.”

JJM Will there be a third volume?

GG I hope so, but it will depend a great deal on how this book does. If it does not do well, I don’t see the publisher wanting a third volume. I do have two other books under contract, and I need a break. But the research is done, and if there is a demand, I expect to write a third and final volume on Bing Crosby.

JJM Ultimately, what is Crosby’s legacy during the 1940 – 1946 era you write about?

GG You can’t write a book about relatively recent American history without at least silently weighing its events against those of the present. To most people, his legacy is that of a Christmas singer and as an unlikely partner for David Bowie. I would hope people go back and investigate some of his great films and recordings. I hope readers will enjoy and perhaps marvel at the unity that he embodied. We read ad nauseum of the Greatest Generation in accounts that too often separate the business of war from a home front defiled by racism, anti-Semitism, internment camps, nativism, riots, and a paranoia grinding along beneath the surface, waiting to emerge in the safety of peace. What sore winners we were. How slowly, reluctantly we adapted our vaunted values to our own country. But there were moments of greatness, sacrifice, and inspiration. We recognize it in FDR as well as other statesmen, military figures, and countless heroes among the citizen soldiers. We are charier in recognizing the glorious achievements of citizen-entertainers. Bing Crosby crystallized what was best in us during some of the darkest years in our history. And as an artist, he has a lot to give us even now.

photo HLC Properties, Ltd

Crosby at the piano in Going My Way

*

Listen to Crosby sing “It’s Been a Long, Long Time”

___________________

Gary Giddins is a long-time columnist for the Village Voice and a preeminent jazz critic who received the National Book Critics Circle Award, the Ralph J. Gleason Music Book Award, and the Bell Atlantic Award for Visions of Jazz: The First Century in 1998. His other books include Bing Crosby: A Pocketful of Dreams–The Early Years, 1903-1940, which won the Ralph J. Gleason Music Book Award and the ARSC Award for Excellence in Historical Sound Research; Weatherbird: Jazz at the Dawn of Its Second Century; Faces in the Crowd; Natural Selection; and biographies of Louis Armstrong and Charlie Parker. He has won an unparalleled six ASCAP-Deems Taylor Awards, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and a Peabody Award in Broadcasting.

______________

A list of memorable Crosby recordings/performances between 1940 and 1946, as chosen by Gary Giddins.

(Unless otherwise notes, all performances are Decca Records; the rest are from broadcasts):

1940:

“Sierra Sue”

“Beautiful Dreamer”

“The Pessimistic Character” (parody version)

“That’s for Me”

“Trade Winds”

“It Makes No Difference Now”

1941:

“The Waiter and the Porter and the Upstairs Maid”

“Sweetheart of Sigma Chi”

1942:

“I Want My Mama”

“Miss You”

“Lazy”

“Walking the Floor Over You”

“White Christmas”

“Moonlight Becomes You”

1943:

“Pistol Packin Mama”

“I’ll Be Home for Christmas”

“Wait for Me Mary,” Bing and Trudy Erwin, from the September 9, 1943 Kraft Music Hall performance

“It Ain’t Necessarily So,” Bing and Dinah Shore, with an introduction by Bob Hope, from the February 24, 1943 Command Performance program

“De Camptown Races,” Bing and Met tenor Richard Crooks, from the February 13, 1943 Command Performance program

1944:

“San Fernando Valley,” from the June 29, 1944 Kraft Music Hall performance

“Is You Is or Is You Ain’t My Baby,”– Charioteers /choir version from radio

“Too-Ra-Loo-Ra-Loo-Rah”

“Don’t Fence Me In,” with Andrews Sisters

“My Baby Said Yes,” with Louis Jordan

“Road to Morocco,” with Bob Hope

“Going My Way”

“People Will Say We’re in Love,” with Judy Garland, from the April 28, 1944 Armed Forces Radio Show

“Sweet Leilani,” with Harry Owens, on Mail Call

“My Blue Heaven.” with Harpo Marx, from the June 17, 1944 Armed Forces Radio Show

“Shoo Shoo Baby” Bing and the Charioteers, on Jubilee

“My Wild Irish Rose,” with Charlie LaVere and audience, from the September 17, 1943 GI Journal program

“My Ideal,” with Les Paul and the Armed Forces Radio Show Orchestra, from Mail Call

1945:

“Swinging on a Star,” from the February 1, 1945 Kraft Music Hall performance

“Hasta Manana”

“It’s Been a Long, Long Time”

“Where the Blue of the Night (Meets the Gold of the Day)”

“Ave Maria”

“I Can’t Begin to Tell You”

“I’ve Found a New Baby,” with Eddie Heywood

“Who’s Sorry Now”

“McNamara’s Band”

1946:

“After You’ve Gone”

_________

Praise for Gary Giddins’s Bing Crosby: Swinging on a Star, The War Years 1940-1946

“A magnificent, monumental biography. Of course the chapters about Crosby in wartime England and France –Der Bingle – fascinated me most, not least his extraordinary mixture of showbiz courage, universal charm and absolutely hard driven energy. The ritual singing of “White Christmas” at the end of each show, producing that huge significant silence among the GIs, is a haunting image and told me something quite new about America at war. I was also impressed by the swift syncopated narrative, and the sly shifts between lyrical and analytical presentation. So how would I sum it up in a phrase ? – a cultural biography to croon over!”

Richard Holmes, author of The Age of Wonder and This Long Pursuit

_____

“I’m a huge fan of Bing Crosby, and this book blazed and boomed over my life like fireworks on the Fourth. Gary Giddins is a masterly biographer, a storyteller with a keen sense of exactly the right details. Swinging on a Star reads like a novel, and this volume is pure gold, if not platinum, spanning the key years in the life of this central figure in American culture. Bing comes alive in these pages, with a glorious cast to accompany him on his many roads to fame and fortune. A dazzling and brilliant biography.”

Jay Parini, author of Empire of Self: A Life of Gore Vidal

_____

“Long-awaited, Swinging on a Star is the scrupulously researched companion to Gary Giddins’s marvelous first volume on the life of Bing Crosby. And like its companion, it brims with music, movies, family drama, religion, love—and, now, war, when the master of jazz performed on a public stage to a country, and most particularly, an armed forces, in need of cheer. With loving precision, Gary Giddins documents those performances—and that man—so that we can participate, hearing as if for ourselves the compassion in Crosby’s song; and witnessing, too, as if first-hand, just how this stoic, incomparable crooner became an American icon. “

Brenda Wineapple, author of Ecstatic Nation: Confidence, Crisis, Compromise

_____

“What an astonishing act of narrative and scholarship Gary Giddins has performed. He has drilled deep into a complex, deeply flawed and extraordinarily talented human being and has brought back not only this fascinating figure but the age that shaped him and which he in turn helped to shape.”

Ken Burns, filmmaker, The Roosevelts and Vietnam

_____

“Gary Giddins is the finest jazz critic of his generation and Swinging on A Star adds another splendid story to the literary mansion he is constructing for Bing.”

Philip Norman, author Paul McCartney: The Life

_____

“Brilliant and unsurpassable: Gary Giddins’s powers as a music critic, film scholar, and historian are all on display in Swinging on a Star, the much anticipated second volume of his Bing Crosby biography. Giddins zeroes in on the war years and richly documents Crosby’s remarkable career as it reached its zenith as singer, actor, and canny business man, not to mention tireless star entertainer to our troops. He raised the morale of all of America and was beloved by millions. Der Bingle was a marvel and so is Giddins. He has captured one of the greatest molders of popular culture who ever lived and I couldn’t put the book down; it is that engrossing. Bravo!”

Patricia Bosworth, author of The Men in My Life: Love and Art in 1950s Manhattan.

_____

This interview took place on September 24, 2018, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician Founder and Publisher Joe Maita

A fascinating interview about an entertainer who dominated Australian entertainment fro many years but never came to our country.

S’wonderful interview! I look forward to reading Gidden’s long awaited 2nd Bing Biography! Jerry, your blog is truly swinging!

Marvelous interview! I read the first volume, Pocket Full Of Miracle, and loved it. Can’t wait to read the latest. Thank you Mr. Giddins. Please do the third volume.

Joe, I’m old enough to remember as a young kid watching “Going My Way” in a theater, along with newsreel clips of Hope and Crosby entertaining the troops. Crosby was all that Gary Giddins says even if his later reputation got tarnished. Thanks for a wonderful interview and for keeping JJM going all this time!

–John Goodman

jazzinsideandout.com

Good to hear for you John…For readers who don’t know John, he was a jazz writer for many years (Playboy Magazine among the publications) and wrote a brilliant book on Charles Mingus called “Mingus Speaks.” I had the great privilege of interviewing him a few years back, which you can read on this site…Do a search within Jerry Jazz Musician for “John Goodman” and you will find the interview. All the best to you, John. Joe

While riding to work with a car full of my fellow teen agers to my first “real job” in 1958, i was rockin along with them to fats and buddy and elvis on the blasting radio. Suddenly came a sound that i guess appealed to my ears alone. who is that? It was bing crosby singing” please”. i, like most kids then knew crosby as the old skinny xmas guy who sang thin and wobbly high notes in a kinda boring way. how could this be? so began a hunt for an answer that has lasted now for 60 plus years. sort of like I’m member of a big cult all based on that same “sound” i heard that morning long ago. The culmination of all my listening? only my opinion: Bing was raised Catholic as i was which helps myunderstanding him fromthe start This above all, good things are a gift from God. you have nothing to do with it. The difference btween bing and me is he really, really felt that. his humility was absolutely genuine. he believed his statements downplaying his talent. As for his “sound”, it was a wonderful one time mashup of all things that it took to form the enigmatic illusion that bing created by himself for himself . he found as much escape in the sound as the world did in listening to it. i’m think it was as instinctual to him as breathing. as i write this im thinking maybe bing was right after all. please excuse my writing and remember that saying about opinions.