PM In addition to Europe, what was going on in the music scene that set the stage for Handy’s success?

DR What was going on musically was the often-forgotten black vaudeville halls, where many of the black performers would play the blues. We also tend to forget today that Memphis was a large enough city to support many cabarets for both white patrons and patrons of color. I say that because we tend to forget that people danced to the blues throughout much of the 1920’s and 1930’s. Today, we would enjoy the music of Charley Patton but dancing to his music, other than maybe a self-conscious folk step, would not be something that would occur to most of us.point.

PM That’s right, in Handy’s 1909 performance of “Mister Crump,” the crowds went wild for it and all started dancing. If the blues had been around prior to “Mister Crump,” why was this considered to be the first published blues song?

DR For a couple of reasons. One of the musicians playing “Mister Crump,” whether with Handy’s expectation or not, took one of the first blues breaks, a deliberate improvisation from Handy’s original score. I imagine that Handy’s eyebrows shot up in disapproval when he heard it, but also saw the delighted response from the audience. Handy was a candid enough business man and artist to probably think, “Well ok, this was not the way I was taught, this was not the way I grew up, but, oh my, do the people seem to like it!” From this point on, there would usually be the allowance of the blues break in Handy’s performances. Unfortunately, Handy himself rarely, if ever, plays the blues break on the few recordings of him that exist.

PM Tell me the story of the “Memphis Blues or (Mister Crump)” and how Handy got swindled out of that song.

DR When you’re writing a book, whether it is a biography or a novel, you have to be careful of minor characters trying to take over your story, and that was the case with Boss Crump. When I was writing that chapter, I felt that I was engaged in a very hard campaign by Boss Crump taking over that chapter. He was such a marvelously colorful and memorable southern politician with such a marvelous mixture of both good and perhaps evil. Later, Boss Crump went on to control the political fortunes of Tennessee up until the 1950’s. If you were President Harry Truman and wanted the Democratic Party to do well in Tennessee, you had better talk to Mr. Crump and do what Boss Crump told you. But at the time, Boss Crump was a young man and was just starting his political career, and it was when he was known as Mr. Crump rather than Boss Crump. In order to popularize his name among the African American political wards and earn their votes, he had one of his lieutenants commission the political campaign song of “Mister Crump,” which later became “The Memphis Blues.”

Handy lost the copyright to “The Memphis Blues” because Handy, as was the case most of his life, badly needed the money. He made a great deal of money, but practically anyone on this planet could handle money better than Handy. He wound up broke having to pay the expenses of his traveling blues bands. He had attempted to sell the score of “Mister Crump” or “The Memphis Blues,” but had been conned by two song sharks who said something like, “Don’t worry Mr. Handy, you put the score up at your expense and we’ll sell them and we’ll all make a lot of money.” The two con men did sell the scores but kept the money and probably said, “I’m sorry Mr. Handy, we tried the best that we could, but we just couldn’t sell this song, I’m afraid it’s a dog. But being the nice soul that I am, I’ll offer you fifty bucks if you’ll sign where all copyrights will be given to me,” which Handy did because he needed the money. Only afterwards did he discover that not only were people whistling, playing and singing “Mister Crump” in Memphis, they were also whistling, playing and singing it in New York, Chicago and other American markets.

PM How important in the life of W.C. Handy was his failure to copyright “The Memphis Blues?”

DR Extremely important so important that he was able to establish the Handy Brothers Music Company that continues to this day and make most of his money not as a blues composer, but as a blues distributor and blues buyer of copyrights. Handy learned the hard way that the key to making good money as a professional musician was not in performing songs, but in owning copyrights of the songs. This makes Handy a little different and a little off-putting for people who were enthusiastic about the blues. A writer in Los Angeles reviewing my book put it very well: “the average blues musician of that time looked like a bank robber. W.C. Handy looked like the president of the bank.” That defines it.

PM Why do think his composition, the “St. Louis Blues” was not initially popular but became popular six years later?

DR For one thing, it was difficult to play even for skilled musicians who were familiar with the blues tempo or the ragtime tempo because it combines so much into one composition. The music within the “St. Louis Blues” is not only a scoring of blues melodies but also some church liturgical music, a slow march tune, and in the middle when that “St. Louie woman with the store bought hair” makes an appearance, the tango. It’s not the sort of song where you could buy the score, take home, sit down at your piano in the parlor and play, and that was how most music was played throughout the 1910’s. Some recordings had not yet become reliable or affordable so the music was supported usually by individuals who bought scores and played them for the entertainment of themselves and their families.

PM Did Handy know the potential of the “St. Louis Blues” for the years it wasn’t popular?

DR Yes and no. I am absolutely convinced he did but on the other hand, Handy always needed money. Astonishingly, Handy apparently signed an exclusive with a vaudeville performer to perform the “St. Louis Blues” on stage for literally no more than fifty bucks. But on the other hand, Handy never sold the copyright until the very depths of his personal poverty in the 1920’s and made very certain to get that copyright back. Handy knew that he had written a piece of art, but was perennially broke and would pawn that piece of art when he needed the money just like in Memphis he would often pawn his cornet for money to buy groceries for his family.

PM Eventually, the artist who popularizes the song is Marion Harris. Why do you think Handy hired her to record the “St. Louis Blues?”

DR Marion Harris is one of those minor characters that we talked about struggling to take over a book and is almost totally forgotten today. I fell in love with her. She had a remarkably erotic voice, very modern sounding and she was one of the first flappers. I wrote so much and so enthusiastically about Marion Harris that my editor basically had to say “Robertson tone it down, tone it down, if she were alive she would be old enough to be your great grandmother.”

PM Well, she was the “Jazz Vampire.”

DR Oh sure, what more would a fella want, she could also be the “Jazz Baby,” maybe both at the same time. What more does a fella want. The point emphasized is that Handy found the perfect crossover performer for that crossover composition he had long been searching for. Although she is forgotten today, Marion Harris was extremely popular not only with white audiences, but had a very large following among African American listeners as well.

PM In Memphis, Handy meets a banker named Harry Pace, and they form the Pace and Handy Music Company. How did Handy and Pace get in touch with each other and why did Handy choose Pace to become his partner?

DR Memphis was the largest city in the area and the big city if you were living in a small town in northern Mississippi, but nevertheless, in realistic terms, was still a small city. Pace was a seriously committed amateur musician, singing in choirs in black churches in Memphis. Given the size of the city and it’s African American population, two comparatively young men, both interested in all kinds of music would almost inevitably cross paths as they did. Pace, at that time, was employed not in the music business, but as a very respected banker at an African American owned bank in Memphis.

PM What kind of challenges Pace and Handy face as African American entrepreneurs in New York City?

DR The greatest challenge may have been for Harry Pace trying to cover bad checks that his partner, Handy, kept writing and bouncing. Which is to say that Handy was a wonderful artist, but couldn’t handle money worth a flip. Pace was a trained banker and a successful businessman in insurance after he left the banking business. But, as to the difficulties sitting aside Pace probably thought, “my partner is a genius but he might just end up bankrupt if I don’t keep an eye on him.” Pace handled the money and had to make that very clear. Pace and Handy were facing, if not discrimination, the fact of being one of the very few black owned and kept alive businesses. It’s very significant to say Handy did not locate their offices in Harlem, but at Tin Pan Alley, which at that time consisted of businesses primarily run by recent immigrants from Germany and elsewhere. Their mindset would have been something like, “We may be a minority business but we’re not going to settle for a minority part in the business. We plan to compete with Irving Berlin and all the other big companies on Tin Pan Alley.”

PM You write about Handy’s trouble with handling his own money and it was one the reasons why Pace left to form the first all black record label, Black Swan Records. What kind of challenges and opportunities did that provide Handy’s company after he left?

DR For those who read my book, I hope they carry away a memory of Black Swan Records because at least two generations before Motown Records, Black Swan existed as a black capitalized business specializing exclusively in African American performers. Ironically, Black Swan failed as a business, but the hapless handler of music Handy and his business continued into the next century. While the idea that Black Swan would record African American musicians performing for an African American audience was promising, Handy was interested in creating a crossover success.

PM During his later years, Handy starts producing spiritual albums and kind of distances himself from the blues.

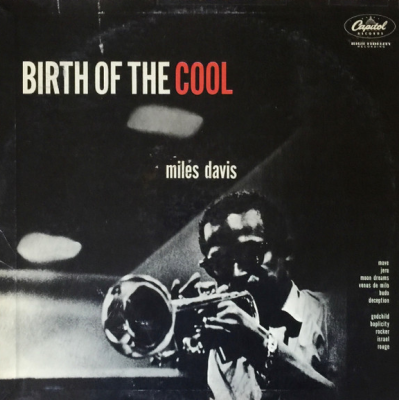

DR He does this, in part, because he realized that as an artist, his time had passed and probably thought “It was a wonderful time while it lasted and that I and the people around me may have done something of lasting pleasure and value.” In the 1910’s and the early 1920’s, Handy moved to New York and fused the “St. Louis Blues” and the “Yellow Dog Blues” and all of those wonderful hits. But, as it became the late 1930’s and early 1940’s, Handy quite cannily realized that there was a newer generation coming along, playing a music that had grown out of the blues, called jazz, which Handy didn’t quite understand and couldn’t quite play. They were also playing big band music and I think Handy realized something like, “I still have much to contribute, but my time in the sun has passed with the early blues.” Handy was not only a proud African American composer but a proud African American who, in the fulfillment of Dvorak’s prophecy, must have thought “I would like very much, both as a business man and an artist to bring to the whole American people, not only the great accomplishment of the folk blues, but the great accomplishment of the black spirituals.”

PM Throughout Handy’s tough trials and tribulations, did he ever consider giving up a career in music for a more conventional job?

DR Never, and that says a great deal about his commitment as a musician. In terms of his sufferings, B.B. King’s remark sums it up: “To play the blues as an African American is to be black twice.” In regards to Handy’s sufferings, he went blind not once, but twice. Once in the 1920’s, from which he fortunately recovered and again in the 1940’s from which he unfortunately did not. This man who loved composing and reading music was blind and would not be able to read a score again.

PM Jelly Roll Morton had some pretty harsh things to say about Handy, essentially declaring himself the founder of the blues and jazz, not Handy. Does Morton have a good case?

DR No. Jelly Roll Morton had some pretty harsh things to say about practically any other musician of color who was not Jelly Roll Morton. I think that’s a continuation of the debate about where the blues originated: New Orleans or Memphis? The honest answer is “both.” So, while Morton may have been trying to make a case for New Orleans in his comments, he was making the case too strongly for himself being the founder of the blues and jazz than anything else.

PM What did Handy think of Morton’s music?

DR Although Handy was not the “Father of the Blues,” he was always a genial individual and a very serious and honest artist. He had admiration for Jelly Roll Morton’s blues and, in turn, he by no means disparaged Morton’s artistic accomplishments. As a private individual, though, Handy talked to his lawyers about suing the hell out of Jelly Roll when Morton was making these charges against him. Although he disagreed with Morton in print about the exclusive New Orleans view of the blues, he did so in a much more tempered and genial way than Mr. Morton.

PM What was Handy’s biggest contribution to the blues musically?

DR A couple of things First of all, the blue note and Handy by no means is the father of the blue note even though in his day it was known as “W.C. Handy’s famous blue note.” Obviously, that anonymous folk guitarist Handy heard at the railway station in Mississippi had been playing blue notes prior to Handy’s use of it. But, one of Handy’s major accomplishments was the introduction and crossover use of the blue note into national popular music. Because of Handy, everyday people in places like Portland, Oregon can hear the blue note. Another contribution, which he sometimes goes without credit, is his introduction of other national music into our national music. The “St. Louis Blues” not only has wonderful passages of black folk and liturgical music; it also has the tango in it. Handy was among the first to be interested in and appreciate the artistic possibilities of American Hispanic music. The Latin-inflicted rhythms that the kids are playing today probably would have puzzled but delighted Handy if he were alive today. That’s another reason why Handy may have been a little disparaged. He was not exclusively the advocate of the rural African American blues he was the advocate for good music wherever he heard it whether it was the ragtime that developed after John Phillip Sousa or the tango played in Cuba and parts of Florida.

PM What was Handy’s greatest contribution to American culture and music?

DR I will always argue for the importance of the “St. Louis Blues.” Handy fulfilled, as much as it can be, the Dvorak Prophecy that there was a great American music to be written and the “St. Louis Blues” is a historic piece of American music. It was black folk music with ragtime and the Hispanic tango beat and is recognized worldwide as a distinctively American tune. The “St. Louis Blues” has been one of the most frequently recorded songs in the 20th and 21st century and if you have written a song that has been covered successfully by both Billie Holiday and Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys, you have written a truly American piece of music.

PM You write that the current generation “associates the blues exclusively with rural Delta musicians such as Robert Johnson, or with New Orleans-based performers such as Jelly Roll Morton ” Why do these musicians overshadow W.C. Handy in the current generation’s viewpoint of the blues?

DR That is a “real interesting pair of short sleeves,” as Handy would say. A “war” is currently going on within the world of blues scholarship, where a handful of musicians and scholar Alan Lomax chose to define the blues as the music of an exploited class in the Mississippi Delta that was created specifically for ideological or political reasons. They certainly were exploited and it was their music, but this denies the urban origin of the blues, which was contemporaneous with the folk musicians in the Mississippi Delta. Also central to this heated argument is the discussion about whether the origin of the blues has been defined too narrowly, and if it ignores urban figures and musicians such as W.C. Handy.

PM Which was more important: the music he created, or the popularization of the music he created?

DR Well, which is more important: the eloquence of the preacher on Sunday, or the fact that he keeps me from sinning until next Sunday? To take the long view, his greatest achievement was his crossover success because it would have been much harder for other African American performers such as Bessie Smith to achieve their success and acclaim had there not been W.C. Handy. However, judged as an artist, his great accomplishment was in his use of words and melodies.

PM Since Handy was not technically the first to play the blues, what does that do to his image as the “Father of the Blues”?

DR Handy’s claim as being the “Father of the Blues” for both marketing and personal pride has opened him up to attack by people other than Jelly Roll Morton and I am the first biographer to say he wasn’t what he claimed to be. There are many fathers and mothers of the blues. The female performers and originators of the blues have also been unjustly forgotten. I kept in mind a metaphor that when the blues was born, it was a beautiful little baby that looked like good coffee with a little cream in it. This baby is African American with a little white and Hispanic in him and there are many mothers and fathers around his bed. Handy is there, Bessie Smith is there, and Charley Patton is probably out in the yard too, and if you kept walking a little farther from the house, damned if you didn’t see John Phillip Sousa in his uniform. They were all more or less the fathers, mothers, or the godparents of the blues. Handy made the blues but he made them in the sense that he made them a success and a self-conscious art. But, he claimed a lot more for himself and that unfortunately opened him to charges that totally reprimand his claims. Handy was about seven-tenths of what he claimed to be.

“Indeed, Handy would be interested throughout his life in the symphonic possibilities of the blues, with their uniquely played minor notes and folk melodies. But he also saw himself as an American composer in the sense of no longer being just another unknown provincial person of color who played European-inspired marches and waltzes. ‘I let no grass grow under my feet,’ Handy later wrote of first hearing the Mississippi blues; shortly thereafter he moved his family to Memphis and organized his blues orchestras and music publishing business. The blues performed as commercial entertainment and sold as sheet music to a national audience promised to make William Christopher Handy, as an American composer, a rich man.”

– David Robertson

_____

In no particular order of preference, David Robertson’s five favorite versions of the “St. Louis Blues:

Billie Holiday, from her album, “No Regrets”

Any version by Bessie Smith

Django Reinhart and Stephane Grappeli, from their album, “Paris 1937”

Glenn Miller, in the fast-tempo version later adopted as a marching tune by the U. S. Military

Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys, in a white-country, two-step swing version.

*

Lyrics to the “St. Louis Blues”:

I hate to see that evening sun go down,

I hate to see that evening sun go down,

‘Cause my lovin’ baby done left this town.

If I feel tomorrow, like I feel today,

If I feel tomorrow, like I feel today,

I’m gonna pack my trunk and make my getaway.

Oh, that St. Louis woman, with her diamond rings,

She pulls my man around by her apron strings.

And if it wasn’t for powder and her store-bought hair,

Oh, that man of mine wouldn’t go nowhere.

I got those St. Louis blues, just as blue as I can be,

Oh, my man’s got a heart like a rock cast in the sea,

Or else he wouldn’t have gone so far from me.

I love my man like a schoolboy loves his pie,

Like a Kentucky colonel loves his rocker and rye

I’ll love my man until the day I die, Lord, Lord.

I got the St. Louis blues, just as blue as I can be, Lord, Lord!

That man’s got a heart like a rock cast in the sea,

Or else he wouldn’t have gone so far from me.

I got those St. Louis blues, I got the blues, I got the blues, I got the blues,

My man’s got a heart like a rock cast in the sea,

Or else he wouldn’t have gone so far from me, Lord, Lord!

__________________

W.C. Handy: The Life and Times of the Man Who Made the Blues

by

David Robertson

*

About David Robertson

David Robertson is the author of three previous biographies, of slave rebel Denmark Vesey, the former U.S. secretary of state James F. Byrnes, and the bishop James A. Pike, and of a historical novel about John Wilkes Booth. His poetry has appeared in the Sewanee Review and other journals, and he has provided political and literary commentary on ABC News and The Washington Post. He was educated in Alabama and lives in Ohio.

__________________________

PM Who was your childhood hero?

DR I would have to say my most admired figure in my early youth I was born and grew up in the 1950s and early 1960s at Anniston, Alabama, among the most bitterly fought sites of the civil rights era in my state was my city’s local journalist, Cody Hall. Cody, the editor at the Anniston Star newspaper, very bravely, and at considerable financial and social risks, took an editorial stand in his paper urging a non-violent acceptance of racial integration by the city’s white residents, and insisting upon the rule of law in prosecuting those who committed violence upon the freedom riders and civil rights workers who traveled to Anniston in those early years. His stand was taken also at a considerable physical risk; the FBI later gathered evidence that the local Ku Klux Klan was assembling explosives in order to bomb Cody’s office and the Star’s printing plant. What is more, Cody wrote eloquently, learnedly, and passionately. He was a combat veteran of World War Two, and was one of the last generation of the truly great journalists in the “Good Night, And Good Luck” tradition. I was honored to have known him.

*

Critical Acclaim for W.C. Handy: The Life and Times of the Man Who Made the Blues

“[Robertson] casts overdue light on Handys essential role in establishing the blues as a popular art . . . A biography of admirable restraint.”

— David Hajdu, The New York Times Book Review

“A remarkable musical journey . . . An overdue and highly readable account of the man known as the Father of the Blues.”

— Mark Rozzo, The Los Angeles Times

“A fascinating look at not only Handys life but the history and business of American music.”

— Publishers Weekly

“At the turn of the twentieth century, W. C. Handy (18731958) propelled the blues from regional obscurity, changing it into a vital tradition that fostered much of American popular music that followed. A native Alabaman, Handy moved to Memphis in 1905 after living in St. Louis and becoming a professional musician whose experience included playing in minstrel shows for racially mixed audiences. He became a prolific composer of songs, including St. Louis Blues and Beale Street Blues, and established Memphis as the blues capital and Beale Street as its main street. Handys accomplishments as singer, composer, band leader, and musician came together in his endeavors as he became more famous and influential. Rich and atmospheric, Robertsons portrayal of Handy is also comprehensive and well referenced. It ought to be required reading for devotees of American music, though it might constitute heavy sledding for casual fans. Readers who persist will be rewarded with a rich basic history of the man and his music and the roots of much of the music we hear today.”

— Booklist

*

W.C. Handy products at Amazon.com

David Robertson products at Amazon.com

_______________________________

This interview took place on July 25th, 2009

_______________________________

Other Jerry Jazz Musician interviews

# Text from publisher.

*

This interview was conducted and published by Peter Maita on September 4th, 2009. Portland, Oregon.

great article and research. However my studies show that Ethel Waters was the first to record St Louis Blues in 1921 and the first to perform it (Vaudeville).

great article and research. However my studies show that Ethel Waters was the first to record St Louis Blues in 1921 and the first to perform it (Vaudeville).