A Conversation with Gary Giddins

*

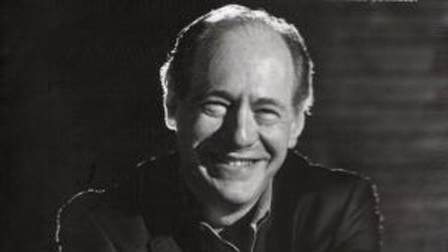

Village Voice writer Gary Giddins, who was prominently featured in Ken Burns’ documentary Jazz, and who is the countrys preeminent jazz critic, joins us in a March 13, 2003 conversation about pianist Cecil Taylor.

Conversation hosted by Jerry Jazz Musician publisher Joe Maita.

________________________________

“I accept the responsibility of having made them (choices). I’m talking about the small part I’m playing in the evolution of music, the gift that has been given to me, to have seen spiritualized the mysteries of the music at an early age. This made my actions predestined. One has to become aware of the force, both realistic and spiritual. It’s about hard work, which is about living to the full extent of one’s capabilities.”

– Cecil Taylor

________________________________

JJM The critic Whitney Balliett writes, “Listening to Taylor takes patience and courage. He wants you to feel what he feels, to move at his speed, to look where he looks (always inward.) His music asks more than other music, but it gives more than it asks.” You wrote, “Taylor’s audience grew slowly. For most people, it was hate at first blush, but often the hate turned to intrigue and then to love.” How do people get beyond the hate and learn to love Taylor’s music?

GG Appreciating his music begins with some sort of initial fascination that makes you want to look more deeply into it. To many people, of course, it is not hate at first blush. When I was teaching a History of Jazz course, I noticed every semester that the students who had classical music training were quite taken with Taylor. They would be a little put off when they first heard Ornette Coleman’s pitch, or John Coltrane might be too complicated, but they would be crazy for Cecil Taylor. Of course, I would play excerpts from certain of his piano pieces, so they might not have had the same response to, say, an hour set. But they responded to his technique, to the excitement of the music, to his ideas.

Taylor is almost like a tabula rasa in the sense that listeners read into him whatever they happen to know about music. People with a classical background will hear everything from Ravel to Messiaen or Mozart to Brahms, and those with a jazz background tend to talk about Bud Powell, Lennie Tristano, Horace Silver or Dave Brubeck, and so forth. While people always seem to hear references to the music that they know, at the same time, whether you love Taylor or not, he doesn’t really sound like anybody else. That is the great paradox, that he is so much an original, yet he calls to mind so much of western music and so much of piano music.

Taylor talks a lot about African music, but I don’t think most people hear that in his work. I think it is a question of responding to his music in an ingenuous way, the way you respond to things that you have to learn to admire. What I mean by that is for many of us, Taylor was put forth as someone who required — as Balliett said in the quote you read — a great deal of courage, much like that required of a reader of James Joyce. A lot of bad teachers steered students away from Joyce by telling them that they couldn’t read Joyce until they had read everything from Homer to Vico and all of the previous Joyce works to get to Ulysses. You could spend a lifetime just doing all the preparation and then you are supposed to carry around a thousand pages of footnotes. What pleasure is there in that? But, just take Ulysses on vacation with nothing else and you will find out how truly pleasurable Joyce can be, as long as you don’t expect to get every single line. Listeners have that same expectation of Taylor, that listening to him will take a tremendous amount of work. It is when you put your defenses down and let yourself respond to the music that you can really learn to love it.

JJM When did you learn to love it?

GG The answer to this question is sort of personal, to tell you the truth. I saw Taylor on an NET television program, and was immediately fascinated by him. I remember that he was doing some stuff with the strings in the piano, which I had never seen anyone else do, and everything about him was sort of amazing to me. Over the next year or so, I bought three albums of his; Unit Structures, which had just come out, the Montmartre trio performance, and the album Gil Evans sponsored to feature John Carisi and Taylor, Into the Hot. The most challenging to me was Unit Structures, which I concentrated intently on and alternately got and didn’t get. I was mesmerized by it without really loving it.

At the time, while I was going to school at Grinnell College in Iowa, I had a girlfriend in Kansas City, and I would often hitchhike there and bring a bunch of albums with me. One night we were making love, and there were a pile of records on her changer, including those of Bill Evans and Bobby Hackett, who she loved. We were just blissing out in bed when I became vaguely conscious of this really terrific music in the background, yet I had no idea who it was. I was trying to concentrate on her and also remember what records I had brought, and then it hit me that it was the Cecil Taylor record. It was like hearing it for the first time, because I wasn’t approaching it with, I don’t know, the alpha part of my brain. I was just letting it bleed into me, and I really got involved with the textures and the way he voiced the saxophones. We were both practically jumping up and down on the bed, shouting, “This is great! This is incredible! We get it!!”

JJM In your role as Concerts Chairman at Grinnell, you brought Cecil Taylor to perform there. I understand you may have taken some heat for that?

GG I went home to New York on vacation, and while there I wanted to get in touch with Taylor and ask him to play Grinnell. Somebody gave me his number, I phoned him, and he invited me up to the Canal Street loft he lived in during the sixties. He was very nice, quiet, and I was quite comfortable with him. We sat around the piano and discussed what we both wanted out of his appearance at Grinnell. He wanted to read his poetry, which I told him we could work in, and we went back and forth, sharing ideas. I remember asking him if I could write out a preliminary contract, and asked if he had any paper. He put his finger on a cocktail napkin that was on the piano that had like a wet ring from a glass on it, and he pushed it toward me. So, I wrote out this little contract on a wet cocktail napkin. I brought the napkin back to Grinnell and gave it to the faculty liaison — who thought I was nuts — and who informed me that it wasn’t exactly legal. I told her it was just a preliminary agreement and that she should get something on paper, so they wrote out a real contract, which Taylor signed, and he came to the school.

It was an amazing week at Grinnell. He definitely gave the students something to think about. He was antagonistic in some respects, and many people just couldn’t accept what he was playing, some even thought he was a charlatan. During a panel discussion he and I did together he said something that I will never forget, which is that a musician prepares and a listener should prepare too, which offended a lot of people. His drummer Andrew Cyrille did an unbelievable solo drum presentation in which he demonstrated a lot of classic drum styles, and showed how they were put together. It was a brilliant demonstration that lasted an hour and was one of the most exciting things I have ever seen of that sort.

Then there was the Saturday night concert by his great quartet, with Cyrille and saxophonists Jimmy Lyons and Sam Rivers. Not surprisingly, there were lots of walkouts, but some people were really knocked out, unintimidated by his music or by him. Even now, when I run into former classmates, they often bring up that amazing Cecil Taylor concert. A faculty member, a wonderful violinist and teacher named Peter Marsh, who led the Lenox String Quartet, had asked to borrow some of Cecil’s albums, and he fell in love with Unit Structures. So he decided to have a faculty party for the musicians after the concert. I walked in with Cecil and I remember Mrs. Marsh coming over and raving to him about the concert, especially the middle part, which was the piano solo, comparing it to Ravel’s Sonantine. Cecil asked her why she brought up Ravel and not Ellington or Bud Powell. A real conversation stopper.

JJM You had some time alone with him during this week?

GG Yes, at one point during a dorm party he asked me what albums I had in my room, so I invited him to come check out my collection. I was really proud of my super hip jazz collection, which he looked at with complete disdain and asked me, “Got any James Brown?” I was crushed. I also remember he was carrying Peter Gay’s Weimar Culture with him; we had a conversation about it and I immediately went out and bought the book, and became a great admirer of Peter Gay. I’ve read several of his books. I guess that’s another example of something I’ve received from Cecil Taylor over the years.

Also, Cecil knew about the fact that Louis Sullivan — the nineteenth century architect who designed Penn Station and Columbia University in New York — designed a building in Grinnell, Iowa that became the Powasheek County Bank. He was dying to see this bank, which is a beautifully designed, elegant two-story square building. We walked into the bank and Cecil went up to the cashier and asked her about the building, which she knew nothing about. He tried to talk to her about Louis Sullivan but she was clearly puzzled by the whole encounter. We left the building and walked through town, and he told me he was looking forward to getting back to New York because he had plans to see Betty Carter, who was going to be singing at Judson Hall, which later became Cami Hall. He was surprised that I knew who she was because, during the sixties, she had pretty much disappeared from view and hadn’t recorded in ages. But I had the album with Ray Charles, and when I mentioned that, he said, “Oh, she’s come a long way since then.” When I got back to New York, she was doing another concert at Judson Hall and I went to see her, which intensified my own interest in Betty Carter — again, thanks to Cecil. Everything about that week with Cecil Taylor was monumental to me. It was a great education.

JJM And it led to an attempt by the campus to impeach you as Concerts Chairman?

GG Ah, yes. The minute Cecil left campus, impeachment proceedings were brought against me for squandering student funds on a “charlatan.” They actually had an impeachment meeting and a vote, which I was not allowed to attend, even to defend myself. There were people on the committee who did defend me, however. I remember sitting in the student union — it was called The Forum — waiting to find out whether or not I had been impeached, and the editor of the school paper, who hated me and all the things I was doing, was really enjoying my discomfort. He made nasty remarks, and I was sitting there, fighting back tears I was so freaked by all of this. Then a bunch of people came running in saying that, like Andrew Johnson, I had maintained my position by a vote, that I had not been impeached. So I stayed on and brought Bobby Hutcherson with Harold Land, Ted Curson with Nick Brignola and Eddie Harris, Ellington, Armstrong, B.B. King, oh, we had fun.

The next year, Cecil was hired at Antioch College and people at Grinnell started questioning themselves — maybe he wasn’t a “charlatan” after all if Antioch wanted him. Then he went to Wisconsin and developed a near-legendary presence in the Midwest because of his teaching, and suddenly I heard people at Grinnell actually boasting about having him first. When I went to a campus reunion in the eighties, everybody was going on and on about all the concerts I had produced, and they especially remembered Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington and Cecil Taylor. The same people who walked out of the concert were now nostalgic about it.

JJM Did this impeachment lead to a more conservative approach to who you subsequently brought to campus?

GG The only two I got in trouble for bringing to campus were Armstrong and Taylor. Regarding Armstrong, we were having a convocation with about fifty famous Americans, among them Ralph Ellison and Marshall McLuhan. Martin Luther King delivered the closing benediction, a powerful antiwar speech. They asked me to book a band for that Saturday evening. My first response was to get Armstrong, but I didn’t think we could. By an incredible coincidence, however, he was touring the Midwest and he had that night free, and we got him for practically nothing. But the student body created a tremendous fuss because they wanted the rock band Big Brother and the Holding Company, which was famous only because of Janis Joplin. She had just left the band, and without her Big Brother was a piece of shit, nothing rock group. Big Brother consisted of three musicians and they were asking $12,000. We later got the entire Ellington orchestra for $4,000! And, come to think of it, there was protest against Ellington by people who campaigned for Archie Bell and the Drells. There were actually people picketing Armstrong. You just can’t make this shit up! On the other hand, those who did come to hear Armstrong — the vast majority of the campus — were completely overwhelmed by him. You couldn’t see Armstrong without being overwhelmed. His appearance was a huge success in spite of everything.

The other reason I got in trouble over Armstrong was because I wanted the college to give him the same honorary degree the fifty intellectuals were receiving, and they refused. I really created a stink about it and I was called to the carpet. They said it was too late to give him a degree now, so their idea of a compromise was to invite him back for graduation and give him one then. This was ridiculous. I said, Do you really think Louis Armstrong is sitting around, waiting for an invitation to come to Grinnell, Iowa for a degree? The chance will never happen again, I told them, and of course it didn’t. Now there probably isn’t a school in the nation, with the possible exception of Bob Jones, that wouldn’t kill for the honor to present an honor to Louis Armstrong.

JJM You are right, you just can’t make this shit up

GG It was quite a time.

JJM Getting back to Cecil Taylor, what is the easiest point of entry into his music?

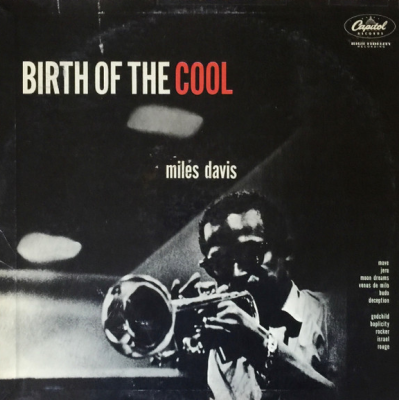

GG Probably through the so-called Gil Evans set. The story about that recording is that Gil Evans had made Out of the Cool and the record company had already photographed the cover for a sequel. They just didn’t have the music to put on it. So, basically Gil Evans gave his imprimatur and the album over to two musicians he admired who nobody would record. One was the trumpeter John Carisi, who was at that time famous for one piece, “Israel,” which he wrote for Miles Davis, and the other was Cecil Taylor. Side one of the album had three pieces by Carisi, and side two had three by Cecil. The pieces by Taylor are beautifully crafted and very easy to listen to. It’s like his last gasp of hard bop before he really breaks loose. Certainly Jazz Advance is a good way to get into him because you can hear him sort of figuring it all out. And the album on Contemporary, with an interesting obscure vibes player named Earl Griffith. Yet I feel sort of condescending to suggest those when I really think you should leap into one of his masterworks like Conquistador! or 3 Phasis or Dark to Themselves or the recent Willisau Concert.

As much as I admire the early records and even love them, I don’t necessarily find them to be an easier pathway into Taylor’s music. I like Taylor when he really becomes Taylor. I like the Montmartre album with Jimmy Lyons on alto and Sunny Murray on drums because you can hear them breaking through, reinventing the music. Before that, while there was a certain freedom to Cecil’s music, where he was creating his own melodic and harmonic language, the one thing he is really jimmied in by is the rhythm. Dennis Charles wasn’t a terrible drummer, but he didn’t know how to break free, which would mean following Taylor instead of keep a predetermined beat. He was just trying to keep the ‘four’ there, while Taylor’s music had to get past that to really fly. At Montmartre, Sunny Murray just did it. Murray basically said, instead of me keeping a beat and you trying to phrase your music in a swinging rhythm that I have already set, you just play and I will make the rhythm follow you. That was the great moment, and at that point the whole music truly becomes free of all constraints, and Taylor absolutely takes off. His genius truly comes to the fore at that moment, and Murray is having the time of his life because they are really listening to each other. The German critic Ekkehard Jost pointed out that Taylor substitutes energy for swing, so that every phrase he plays — whatever rhythm that generates is what the ensemble has to work with. And for the band to work they have to listen. People complain that Taylor doesn’t listen to anybody, that everybody has to follow him. But if you look at records like 3 Phasis — which is one of my favorite Taylor albums — you hear passages where he is responding to what everybody else is playing, basically doing the work of an accompanist. One of my most vivid memories of his time at Grinnell is of Cecil feeding quarters into a lounge jukebox, and then sitting down at the piano and playing along with Aretha Franklin records. He just basically backed her up for about half an hour — not in a manner that she would necessarily have understood, maybe, but it was an incredible experience. He really is something.

JJM Miles Davis once walked out of Birdland when Taylor played, and, after a Taylor performance, Leonard Feather once said, “Anyone working with a jackhammer could have achieved the same results.” Who were his initial critical champions?

GG I’m not sure. Whitney Balliett was very impressed with him the first time he heard him — which was at the Newport Jazz Festival — and wrote a positive review. The review wasn’t so much about the music but of the experience of watching him work. That was an important review. Martin Williams paid attention and put “Enter, Evening” from Unit Structures on the Smithsonian Collection of Classic Jazz, so he was certainly out front. There was Leroi Jones, of course, although he came a little later — by then it was already into the sixties. I don’t recall any major essays from the early period but there must have been some.

I believe the first truly brilliant analysis of Taylor’s music came from Ekkehard Jost, in a very important book he wrote called Free Jazz. The Taylor chapter is exceptional. It provided people with a different way to get into his music. For the most part Taylor wrote his own liner notes. Nat Hentoff produced a couple of excellent sessions for his label Candid, but I don’t recall if Nat wrote about Cecil or his music beyond that venture.

Regarding Miles walking out on him and how musicians felt about his playing, Cecil once did a concert at the George Wein festival in New York– it may have been when Kool was the sponsor — and Oscar Peterson played the first half of the date and Cecil the second. Of course when Cecil played there were audience walk-outs. I remember Benny Carter was livid because he couldn’t understand Taylor’s music one way or another, and other musicians felt it was insulting to have a great artist like Oscar Peterson followed by this “noise.” Yet there were other musicians in attendance who said the exact opposite. To them, Oscar Peterson was like a machine. One musician said to me that Cecil Taylor provided faith that there may actually be a future for this music. So, people respond to art in different ways, and that is what you would expect from a genuinely avant-garde artist. A musician who is ahead of the curve is supposed to be controversial and is supposed to start arguments otherwise he can’t be ahead of the curve. If a James Joyce or a Picasso or a Taylor or a Coltrane didn’t create debate, they would have been conventional artists. I like the conventions. But how boring life would be if you had nothing but conventions.

JJM You wrote, “One can’t help but suspect that if Taylor were white he’d have played different venues, enraged a different forum, and attracted different champions.” If Taylor were white, would his music be more categorized as classical rather than jazz?

GG Yes, it is absolutely true, because he always has generated a tremendous fascination in the classical world. If he had been white and he came from the Academy yet played exactly the same music he plays now, I think he would have had a different following, a different set of critical responses, which would have led to different kinds of label affiliations and different kinds of jobs. But, because he is black, and because he comes out of the jazz milieu, and because he worked with jazz musicians, he was stereotyped in that world. Thus, to people who want to hear jazz in a certain way, Taylor was just a charlatan and they didn’t know what to make of him. Taylor considers himself a jazz player, and I think he definitely is. His impact on jazz has been immense. Every pianist, whether they play “out” or not, has been liberated by Taylor’s keyboard attack. Tommy Flanagan went to hear him when Cecil was playing duets with Elvin Jones at the Blue Note a few years ago. He stayed through two sets and was set to open at the Vanguard a week or so later. When we left I said, jokingly of course, “So will you be playing any Cecil Taylor tunes?” He said, “No, but you can bet I’ll be thinking of them.”

JJM Who were some of the players in the European classical avant-garde that Taylor listened to?

GG It is hard to say. He told me once that when Ligetti was a big deal he went out and got the scores of his work. Poulenc as well. He said he was looking at the scores and thought they were very interesting but then he realized that he didn’t care about music that was “just interesting,” if it doesn’t move him. I am the same way. I totally identified with that. I find it very difficult to listen to music that is only intellectually imposing or where virtuosity alone is the attraction. There was a classical avant-garde pianist in New York that a classical critic I knew took me to hear one night. He played tremolos for an hour, which was an amazing technical feat. I mean, just try to imagine the control of playing perfect tremolos for an hour. But at the end of the day it was just a goddamn hour of tremolos. I thought it was hateful, and I asked the critic to explain it to me, and he talked about the concept and the ideas. He articulated it very well but I found it stupefying. Much of the old classical avant-garde, from the era of Schoenberg or Berg, is concerned with getting away from the tempered scale, but at its best that music is terrifically emotional — “Moses and Aron,” for example. I was told by someone once that they heard Wynton Marsalis on the radio talking about me, and he said that the trouble with Giddins is that he only listens emotionally. I think Wynton is exactly right, and that may be a failing of mine, but that is what I want from music. If it doesn’t move me, I just don’t give a shit.

JJM Yes, and Taylor once said that “technique is a weapon to do whatever must be done.”

GG Exactly, and Taylor’s music is very emotional, it is about being completely involved in that moment.

JJM What did he learn from Ellington?

GG What he probably learned from the jazz players like Ellington, first of all, is sense of touch, an attack on the keyboard that he must have admired. But he also may have learned the basic rules of what a jazz performance is, theme and variations, and the way you learn to improvise on a chord structure, because he does that on all the early records. He did a record called Love for Sale, where he plays three Cole Porter tunes, and on the other side he has original pieces, and Ted Curson told me once that he and Bill Barron rehearsed every day for a year with Cecil to make that album and play one gig. Think about that.

He may have picked up some formal ideas and a feeling of fraternity from keyboard players like, Brubeck, Silver, Tristano, but I don’t know. The fact is, his attack is utterly unique-it’s as instantly recognizable as that of Monk or Bill Evans or Ellington. He may have learned a lot from classical composers like Messiaen. Stanley Crouch has argued that very persuasively, because you can hear some of that in his music unmistakably. But finally — and this is obvious to even the most unsophisticated ear in the world — his work is something extremely original that doesn’t really sound in its composite final form like that of anybody else. It is pure Cecil Taylor.

JJM What was his boldest achievement?

GG He reinvented the piano recital. That’s pretty damned bold. He invented a new keyboard language, and a new way to order the elements in an ensemble by having other instruments expand on ideas developed at the piano.

While I say that, I want to say very decisively that I don’t believe the new language was an improvement on what came before, and I certainly don’t believe it puts classic jazz into a darker light or any nonsense like that. Taylor doesn’t make me respect Ellington or Bud Powell any less. On the contrary, I respect them more. What he does is his way, not the only way. I feel silly saying something so obvious, but I often encounter people who are offended by Taylor or Ornette Coleman or any cutting-edge musicians because they think that they are leading by example and putting everything else down and saying this is the way jazz is going to be. It’s not true. No one says or believes that. Cecil Taylor is a fan of Errol Garner. But he created a music that reflects the world he knows. If his generation had done nothing but recycle Charlie Parker cliches, jazz would have become museum music, a Dixieland music. To me, “Dixieland” is like what “Chinatown” means in the movie Chinatown, where it becomes a metaphor for “leave it alone.” “Dixieland” is this world where nothing ever changes — not the clothing, not the music. Everything is the same — it is a tourist attraction. The whole idea of music is that what is great remains great forever, but there has to be somebody moving it along to explore the next moment.

JJM That is a critical conversation in jazz music right now.

GG Sure. As Wayne Shorter has said, if you close off all the inlets and outlets to a lake, the lake will grow fetid and die.

JJM Do Taylor’s eccentricities as a musician extend to his character as well?

GG Everything about Taylor is, in a sense, self-created, and not just the music but the way he appears on the stage — the singing, the dancing, the poetry, the knit hat, the flowery clothing. He has created his own world. But, he is a very thoughtful, intelligent, decent man. He is the easiest interview in the world. All an interviewer has to do is remember to turn the tape over every forty-five minutes, because he loves to talk. If he is in a good mood, he is a fountain of ideas. On the other hand, I remember calling him up for an interview and he said he wasn’t interested and hung up the phone. There are no constraints in his behavior; either you accept it or you don’t.

I have always found him to be enlightening. We don’t interact personally that often but I don’t think I have ever had a conversation with him where I didn’t come away having learned something. He is witty and amusing and insightful. During the time when he began opening each concert with a vocal prelude, I wrote a piece critical of that. I ran into him on Eighth Street and he told me the reason I had a problem is because I don’t like the human voice. I said, “I like Sarah Vaughan.” He said, “Oh, anybody can say that!” A great line. Taylor and Sonny Rollins are among the few musicians that I need a fix of at least once a year. I have to go hear them, and every time feels like the first time. It always feels like I am hearing something I’ve never heard before.

I do think he has grown enormously. I went completely nuts last year over the Willisau Concert, which I made my record of the year. Everybody I played it for has that response. It is a record that is hard to find in the United States, yet it may be the greatest solo recording he has ever made. When I play it for people, the first minute or so, you can just see their faces lighting up. People become immediately entranced by it because it is so powerful, so confident, and so composed. However, the faces begin to sag after four or five minutes when they realize what they are listening to is a fifty-minute piece and they don’t know how to deal with that. My feeling is, that’s where the preparation comes in. You teach yourself how to listen to a longer piece of music. You know how to do that at an opera, or with a classical piece. There is nothing new about this problem, because if you read the original reviews that greeted Beethoven’s Third Symphony — which was the first very long symphony — critics were outraged by the presumptuousness of the length. One critic wrote that it was inconceivable that there would ever be an audience willing to sit for a forty or fifty-minute symphony. Beethoven’s response, eventually, was to write a ninety-minute symphony. The audience finally figured out how to keep up with him. Today, of course, a performance of the Ninth Symphony in Central Park will draw 100,000 people, and they will thrill to every measure. They know the piece. They know the melodies.

I don’t have that problem now with Cecil Taylor. I find that his fifty-minute pieces fly by, and I look forward to them. I understand how they work. There are certain technical things that he does on the piano that I just wait for in the same way that when I listen to Roy Eldridge, at some point I know he is going to start playing amazing high note passages, and I wait for them. They are thrilling when they come. Taylor has these cascades that he plays, arpeggios and bounding bass lines that are all part of his language. But there are other passages that will be extremely meditative, almost whispering. He touches the keys in such a way where you don’t know where the pressure is coming from to sound the note because it is so soft and delicate. He has total control of dynamics. From a purely technical point of view, his control over the keyboard is astounding. Despite how quickly he plays and how much velocity and strength he uses, you never feel that he is playing wrong notes or that you are hearing accidental minor seconds because his fingers hit the crack between the two white notes or anything like that. There is always a tremendous sense of control, and as you learn to live with his music and you listen to it more and more, the length becomes less and less of a factor.

JJM I hit the play button on Silent Tongues in the car last night while my fourteen-year-old son and his buddy were with me, and you should have seen the shock on their faces. My son’s friend was giggling hysterically, claiming that his four-year-old sister could play the piano better. I did my best to explain that this is music that requires patience to appreciate, but, it was clear I had to hit the eject button if I wanted to escape alive.

GG That reminds me of how I felt when I borrowed my first jazz album. I was about thirteen, a couple of years before I actually connected with jazz. I had been listening to rock and roll and classical. So I put this jazz record on while my mother was making dinner in the kitchen, and she asked me who I was listening to. She said it sounded like they are tuning up, which is what it sounded like to me. I couldn’t make head or tail of it once the theme ended. And, you know who it was? It was Cannonball Adderley. So, if you don’t have an ear for it, it is very easy to question yourself about what they are doing, it truly may sound as if they are just playing notes. That Cannonball record was actually one of the most melodic albums he ever made — The Cannonball Adderley Quintet In Chicago, with Coltrane — but at that time in my life, it was incomprehensible. So, it doesn’t at all surprise me that people have that response to Taylor. It is just one of the reasons why we need more jazz education, because this music is not in our lives and we don’t know how to listen to it.

JJM You had a special experience witnessing Cecil in the studio.

GG Yes. He did two albums for New World, on which Sam Parkins was the producer, and I was asked to write the liner notes for one of them. I was invited to the sessions, which was quite a thrill. During the session, I heard him play the piece that became 3 Phasis three times. The first time he played it the piece was only fifteen or twenty minutes long. The second time was maybe thirty or thirty-five minutes. Then he did another take which was quite long and quite good, but Jimmy Lyons didn’t like his solo and Cecil thought one of the episodes wasn’t really working. Now, I had listened to all of them, and so I was beginning to understand and get involved in what worked and what didn’t. It was like what Ornette Coleman said, that he didn’t know he was on the right track until he knew he could make mistakes. So I was beginning to hear the mistakes and understand the way this sextet worked.

After Lyons complained about his solo, they decided to do another take. They started recording it a little before eleven PM, and they had to be finished at midnight or they would go into overtime and people would have to leave the studio, and the record company would incur additional costs, that sort of thing. Parkins was very concerned about that, but he didn’t show it to the musicians. He was a very solid, canny producer who wanted to get the best performance he could get. So, they started playing and those of us in the studio were completely stunned — it was a brilliant performance. About two-thirds of the way through, Ronald Shannon Jackson the drummer picked up his mallets and he started really rocking, and we wondered how that would play out. Cecil totally responded to it and the whole band got into it. Then it came time for Lyons to play and he was superb. By now it is like 11:55 and Parkins made a comment about how he hoped they’d finish by 12. Well, Taylor ended the piece seconds before the second hand struck midnight, which was incredible. How did he do that? All I know is that they finished and those of us in the control room were screaming, excited by how great it was. And Cecil says, very laid back, “Well, you know, we thought it was pretty good too.”

Every time I play that album it comes back to me. It’s a difficult, daunting piece of music, and it was remarkable to see how it developed, to see what was pre-planned and what wasn’t. He calls his music “unit structures,” where everything is constructed in units, so in a sense, the piece consists of certain things that have to happen. This is the section for the violin and trumpet, this is the section for Lyons, this is the piano section, and so on. All of the sections have to happen one after another, but there is no rule about how long each section has to be, or how it is going to go down. So, in one take the trumpet/violin duet may go on for a couple of minutes and during the next take they might be really inspired and go on for ten or twelve minutes. As long as everyone is working and Taylor and everybody else is happy with the general feeling of the performance, they take it as it comes. At least that’s how it seems to me.

JJM The critic Scott Yanow wrote, “Soon after he emerged in the mid-fifties, Taylor was the most advanced improviser in jazz. Five decades later he is still the most radical.” Would you agree with that?

GG Now we are going to get into semantics, because I don’t know what that means. Is he more “advanced” than Thelonious Monk? Is he more “advanced” than Fats Waller? I don’t know what “advanced” means. If you have the genius to play something that is completely yours, nothing could be more “advanced” than that. I don’t see Taylor as being more “advanced” than Bud Powell or Monk or Ellington or any of the great figures.

Is he radical in terms of what he plays? Yes, radical is a word I can agree with, and I would say that he is probably still the most radical of musicians in the sense that his music is so completely indigenous to him and beyond even the shadow of compromise. A lot of people who use elements of Cecil’s music or his techniques blend them in with other techniques, whereas with Taylor, you feel that all of it is generated by him. You don’t want Cecil Taylor to play a standard. You don’t want him to suddenly say, “Okay, I am going to do a blues in B flat.” Once you become involved in his music you just want to hear what he has to say, and I think that has been the case for a very long time.

After Taylor won the MacArthur Grant in 1989, rather than put the money in the bank which is what most people do, he rented Alice Tully Hall in Lincoln Center to play a concert on his sixtieth birthday. It was a wonderful evening. I brought a friend of mine who is a rock and roll fanatic, and I kept warning her about his music, telling her that it was going to be more difficult than anything she had ever heard. I told her that I was going to stay, but if she didn’t dig it, she didn’t have to feel obliged to do so. I was going on and on with these warnings. But she absolutely loved it. She couldn’t get over it. She ran out and bought lots of Taylor’s records. Now, whenever I see her, she still talks about that evening. So, I suppose that-to return to the idea of first blush–either you get it or you don’t. To me, the great thing about his genius is that it exists, that he does something nobody else can do.

________________________________

Gary Giddins products at Amazon.com

Cecil Taylor products at Amazon.com

_______________________________

This interview took place on March 13, 2003

*

If you enjoyed this interview, you may want to read our conversation with Gary Giddins on saxophone great John Coltrane.

[…] divided musicians, too. Critic Gary Giddins recalled seeing Tommy Flanagan, a more traditionally swinging pianist, at a gig and asking whether he […]