.

.

In a 2009 interview, James Gavin, author of Stormy Weather: The Life of Lena Horne, discusses the challenging yet inspiring life of one of the 20th century’s most revered entertainers

.

.

___

.

.

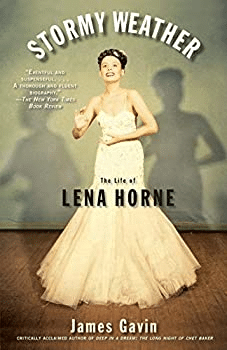

James Gavin, author of Stormy Weather: The Life of Lena Horne

James Gavin, author of Stormy Weather: The Life of Lena Horne

.

___

.

.

.

…..Drawing on a wealth of unmined material and hundreds of interviews – one of them with Lena Horne herself – critically acclaimed author James Gavin gives us a “deftly researched” (The Boston Globe) and authoritative portrait of the American icon. Horne broke down racial barriers in the entertainment industry in the 1940s and ’50s even as she was limited mostly to guest singing appearances in splashy Hollywood musicals. Incorporating insights from the likes of Ruby Dee, Tony Bennett, Diahann Carroll, and Bobby Short, Stormy Weather reveals the many faces of this luminous, complex, strong-willed, passionate, even tragic woman – a stunning talent who inspired such giants as Barbra Streisand, Eartha Kitt, and Aretha Franklin.#

…..Drawing on a wealth of unmined material and hundreds of interviews – one of them with Lena Horne herself – critically acclaimed author James Gavin gives us a “deftly researched” (The Boston Globe) and authoritative portrait of the American icon. Horne broke down racial barriers in the entertainment industry in the 1940s and ’50s even as she was limited mostly to guest singing appearances in splashy Hollywood musicals. Incorporating insights from the likes of Ruby Dee, Tony Bennett, Diahann Carroll, and Bobby Short, Stormy Weather reveals the many faces of this luminous, complex, strong-willed, passionate, even tragic woman – a stunning talent who inspired such giants as Barbra Streisand, Eartha Kitt, and Aretha Franklin.#

…..In a September 18, 2009 interview with Jerry Jazz Musician associate editor Peter Maita, Gavin discusses the challenging yet inspiring life of one of the 20th century’s most revered entertainers, Lena Horne.

.

.

___

.

.

photo via Wikimedia Commons

Lena Horne in a 1946 publicity still for Till the Clouds Roll By

.

“The publicity extolled her as a black woman who had battled racism and crushing loss with ultimate dignity, while conquering almost every corner of white-dominated show business – Hollywood, Las Vegas, Broadway. In an age when black film actresses were confined either to low-budget “race movies” or to playing maids or whores, Horne was the screen’s first Negro goddess and bowed to no one. Regal and classy, she helped redefine white America’s image of the black female.”

– James Gavin

.

___

.

PM You conducted an interview with Lena Horne in 1994. Did you subsequently interview her specifically for this book?

JG No. The interview you refer to was done for the New York Times. After having been in hiding, more or less, for several years, Lena had made her first album in a long time, and was on the brink of her final renaissance, which would include taping a live special for A&E. Since she’d fascinated me since I was a child, I jumped at the chance to interview her. That would be the only serious time I would ever spend with her. I spent two hours and fifteen minutes with her in a hotel room and asked her all the questions I’d always wanted to ask. No one else was there.

PM She didn’t have a stable family life while growing up. How did this effect her view on life?

JG Permanently and profoundly. The chaos of her early years instilled in her a feeling of being unwanted, of rejection and alienation, and it left her feeling very alone. When you trace her life and her art, you see a woman mostly isolated – either in cameo solo numbers in her M-G-M films, out on the nightclub floor doing her cabaret act, or on concert stages. The peak of her career was her one-woman show, The Lady and her Music, which ran on Broadway for over a year.

PM Her grandmother Cora raised her to become an adult at an early age. Lena once spoke of this, saying, “She never made a child out of me. I was always an adult.” Did this upbringing shape her stoic personality?

JG She was raised to be a warrior; her grandmother had warned her to never let anyone see her cry. There were reasons for this. Cora felt that a black person could only survive by being very strong, and never dropping one’s guard. Lena built high walls around herself to keep pain and danger from getting in. As she once admitted, this also kept out a lot of the good things; she became extremely defensive and quick to push friends away. It brought her a lot of sadness and loneliness. But it also made her a survivor. She’s still alive at age 92. While she’s extremely fragile, clearly she still has that fighting mechanism her grandmother instilled in her.

PM Why was she was chosen, at age 16, over “an intimidating number of young black women” to be on the Cotton Club chorus line?

JG Because she was gorgeous, fair-skinned, and could dance a little bit. The defining phrase of a Cotton Club girl at that time was “tall, tan, and terrific,” and the job depended much more on looks than on dancing ability. Being fair-skinned was definitely advantageous in the black community – at the time, the lighter you were, the more acceptable you seemed to the white majority. Soon after they hired her at the Cotton Club, they found out how charismatic she was. So, she didn’t stay in the chorus line for long.

PM What was the Cotton Club like at the time she was hired?

JG The Cotton Club was high-level black entertainment. But these all-black shows were largely presented by white people, for white people. This was a segregated club built to invoke the atmosphere of an old southern slave mansion. Outside, the entrance looked like a log cabin. The club was very expensive, very elite, and attracted presidents, stars, and all the big celebrities of the day. But the patrons had to be white, except for a select few, like the boxer Joe Louis, who was one of the most celebrated black men of the day. Joe would be allowed to sit at a little table in the rear of the club, where celebrated blacks or family members of the cast could sit.

The shows themselves were very fast moving, and choreographed to the hilt. They were extravagant productions featuring the most talented and exciting black performers of the day. The Cotton Club was their holy grail, but Lena Horne came in and saw a disturbing picture. It offended her to look out into an all-white sea of faces. She sensed the condescension in their enticement. The backstage conditions appalled her; for instance, the customers, of course, had their own bathroom, but the chorines had to use a sort of potty. Most of them were proud to be where they were and didn’t complain, but Lena saw things through a much more enlightened lens.

PM She trashed the Cotton Club, even though it provided her with her first exposure…

JG Yes. She thought it was a hotbed of indignity. But without a doubt, the Cotton Club is an endlessly fascinating place. Seventy-plus years after it closed, people are still talking about it.

PM Early in her career, Lena Horne struggled with her singing and the reviewers agreed, yet she continued to become a bigger star. Why did her popularity grow without having the singing qualities of some of her contemporaries?

JG By the time she’d reached MGM in 1942 she had actually grown into a fine singer. But she knew that her looks, more than anything else, had made her career possible – specifically, her Caucasian-style beauty. The phrase “Black is beautiful” didn’t exist then; it wouldn’t appear until the 1960’s. In Lena’s time, if you were black and considered beautiful, it usually meant that you reminded people of a beautiful white woman. Lena had not only the beauty but a refinement to match. And she was determined to get things right. When you listen to her very first recording from 1936 with the Noble Sissle orchestra, “I Take To You ” – a cute little novelty song – you hear what a hard worker she was. She was dead in tune all the way through, and even though she was very young, she tried so hard to sound worldly. Lena sought out teachers and musicians to help her develop. Eventually, she became a damned good singer.

PM How important was her experience working with Noble Sissle on her career and the way she lived her life?

JG He was one of her teachers. Lena wound up working with Sissle as a kind of escape from the Cotton Club. She was itching to get out of there, and Sissle hired her in 1935. He was unique at that time – a black bandleader whose orchestra was so mannerly and debonair that they were hired to play high-echelon society events. Lena fit Sissle’s definition of a “lady,” and he groomed her all the more in that direction. He taught her to keep her chin up and her dignity intact at all times, no matter what kind of racist abuse she encountered. So he was another person telling her to keep her guard up. It helped make her even more suspicious of people and their motives.

PM How did her position as the first African American woman to sign a contract with a major motion picture company – MGM – impact the black community and black entertainers?

JG In fascinating ways. Up until that time, black entertainers were presented almost exclusively as social stereotypes. A genre known as race movies were trying to change that. Race movies were a thriving industry at the time – all-black films that were made on a shoestring and shown in black theaters. The production values were usually squalid, but at least these movies provided work for black actors and strove to eliminate racist stereotypes. Hollywood, however, was still exploiting those clichés shamefully. Lena was singled out by the NAACP’s executive secretary, Walter White, as the best performer to revolutionize Hollywood’s attitude toward black people – to show white America another an anti-stereotype. And even though she wound up being very unhappy in her role as a “symbol,” Lena served as the bridge to a more enlightened time. White’s experiment worked.

PM Without Walter White’s strong guidance, would Horne have been less picky about which roles to play, or to have felt less pressure to be a role model for the black community?

JG Lena Horne was presented onscreen as a goddess, and she got a degree of respect that no black performer in Hollywood had ever received. Would M-G-M have discovered her without Walter White? I would have to say probably not. But there were many reasons why M-G-M signed her. She was beautiful, likable, professional, and damned good at what she did. There were also political reasons why Hollywood wanted her. The black consumer audience was growing, and to have Lena in M-G-M’s splashy white musicals, showcased so glowingly, was good for business.

PM You call Horne’s performance of “Stormy Weather” in the film Stormy Weather her “defining image.” Why?

JG That scene of her standing on a nightclub set, alongside a window in a house with a storm going on outside, is the clip of hers that gets shown the most. It is also her defining image because “Stormy Weather” became her signature song. At the time, Lena was still too guarded to dig deep into those tortured lyrics. Ethel Waters, who introduced “Stormy Weather” at the Cotton Club, was a lot more dramatic. Naturally, when Lena got her song, Ethel was mad as hell, and felt resentful and threatened. Ethel was on her way down then, and Lena was the fine young thing that everyone was making a fuss over. But over time, as Lena blossomed expressively, that song would display all the pain, the rage, the struggles and turmoil that Lena felt.

PM You said that Lena Horne’s films, Stormy Weather and Cabin in the Sky, would go down in history as milestones in black cinema. In the immediate wake of these two movies, were more respectable roles being offered to African Americans?

JG Those two movies did not make Walter White happy. His goal was desegregation, and he didn’t see the value in an all-black musical. Yet the casts in those two films are fantastic, and Cabin in the Sky was directed exquisitely by Vincente Minnelli. Those movies were, in a sense, high-class race movies, and the splendor of black talent they featured drew white audiences into the theaters.

PM She always dreamed of having a lead role in a movie, but there were so few opportunities…

JG Interestingly, part of the Lena Horne myth is that it was written into her contract that she would never play a maid. But just after she’d signed with MGM, she tested for the role of Jeanette MacDonald’s maid in the film Cairo. She didn’t turn the part down; she just didn’t get it. It went to Ethel Waters. In her final days at MGM, Lena told a reporter that she would have played a maid if the role was interesting enough. But to show her in a maid’s uniform would have defeated the purpose of Lena’s presence at MGM. Throughout her years there, the studio struggled to find speaking roles for her, but those were extremely racist times, and MGM encountered many obstacles. As it happened, the way they presented her turned out to be right on the money, because those gorgeously produced numbers showed off all of her strengths – and delivering lines was not one of them. MGM helped create a Lena Horne who was very mysterious, sexy, who wore fabulous clothes and said little. The experts who worked there, notably Kay Thompson and Lena’s future husband, Lennie Hayton, also taught Lena how to sing. All of these factors created the Lena Horne of legend.

PM Did she feel like she was letting down the black community for not playing in any major roles?

JG I don’t think that entered her mind at all. I do think she felt a strong sense of rejection in Hollywood, because she wasn’t allowed to interact with white performers onscreen. For a woman who had grown up feeling unwanted and alone, Hollywood was a bitter pill to take.

PM In the spring of 1948, the playwright and screenwriter Arthur Laurents described a Lena Horne club performance he witnessed as “…the moment she came to life as a performer. That was a Lena Horne that no one had ever seen.” What made this era’s Lena Horne so different?

JG By that time she was really losing patience with Hollywood. Up until then, the training she’d undergone to always be a well-mannered lady and to watch her step were still in place. Prior to the 1948 film Words and Music, Lena had a certain haughty edge to her, but also a lot of sweetness. By 1948, she’d really started to bare her fangs, because she was tired of the way Hollywood was treating her. Her anger began to penetrate her singing, which created a fiery Lena Horne that was really exciting. Her rage came out as this ferocious, fiery sex appeal.

PM During her time in the show Jamaica, she became intensely distressed, saying things like, “I hate myself” and “I’m depressed in a way I haven’t been before.” Why was she so relentlessly hard on herself during this period, or for that matter, nearly every stage of her career?

JG Insecurity. The pressure of feeling scrutinized very closely by everyone and perhaps not measuring up. In the case of Jamaica, Lena had never carried a Broadway show before, and she was terrified. Jamaica featured many young black dancers, and Lena felt their success rested on her shoulders.

PM Did she want the responsibility of being a symbol for the black community?

JG She may not have wanted it, but she certainly accepted it. Lena was tremendously ambitious. In later years, after her disappointments had piled up, she tried, in effect, to disown her career by saying that she had never really wanted to be in show business – that she had only entered the Cotton Club because it was the Depression, and her mother was sick and her father couldn’t get a job, so she had to be the breadwinner. But I don’t believe it.

PM What made Horne an accessible African American performer to the white audience at a time when racism and discrimination were abundant?

JG Number one, her beauty, which, in the eyes of that audience, fit a Caucasian mold. The same could be said of her refinement, her grace, her diction, her repertoire. A “blacker” personality would not have had her particular opportunities in the show-business world of the time; certainly not in Hollywood.

PM She was criticized for lacking any “black musical influence,” yet her lighter skin color made her a more accessible crossover success. How did these mixed signals affect her ability to find her own identity?

JG She never really knew who she was, or what she was supposed to be, and she felt resentment from both sides. Lena was a fair-skinned black woman born of the so-called black bourgeoisie – a class that did a lot to help Negroes to assimilate into white society and to function professionally. But Lena’s family, like much of the black bourgeoisie, harbored great hatred of whites – even while priding themselves on their fair skin, which was a great symbol of class distinction. What confusion! Lena, of course, became a darling of the white show-business world; that was the world she pursued, and it created an emotional tug-of-war for her throughout her life. At times she felt like a traitor to her own people – this in spite of all the stands she took on their behalf, all the inspiration she provided them.

PM Although she rarely ever saw her father as a child, she calls him “the love of my life” as an adult. Can you describe their adult relationship?

JG Their adult relationship was the same as it was when she was a child; he wasn’t around much. At the end of his life, when he was ailing and needed her help, Lena finally got to spend some serious time with him. Teddy Horne had deserted the family when Lena was still a child. He would reappear now and then and shower her with gifts, but he was a distant and mysterious figure to Lena. Certainly her mother Edna didn’t encourage his presence in the young girl’s life. They spent some time during Lena’s early days in Hollywood, but his apparent rejection of her proved tremendously painful to Lena.

PM She referred to another man she loved deeply, Billy Strayhorn, as her “soulmate”…

JG Yes, he became a sort of father figure to her. She adored his refined tastes, his soft-spoken manner, his worldliness, his intellect, and of course his talent. She felt safe with him, and felt she could let her hair down in his company and hot have to “be” any particular way.

PM Would you consider Horne’s specific demands in her professional career as selfish or as revolutionary?

JG Both. Lena was driven by a sense of great personal rejection – from her family, from society – and her struggles to find a place for herself and to maintain her dignity resonated with a huge number of people. I think that something similar can be said of most of the great civil rights leaders. Like them, Lena was so determined that she fought her way past tremendous obstacles and placed herself in a position where she could effect change.

PM In the early sixties, Horne becomes an active participant in the civil rights movement. Was this a way to improve her image or did she really want to make a difference?

JG She wanted to make a difference, but she also wanted to make good with her own people, to finally feel as though she were one of them. She yearned for their acceptance. When I interviewed her in 1994, Lena recalled her late-’50’s and early-’60’s lifestyle as a “black ivory tower.” She was working in upscale white venues – the Coconut Grove, the Empire Room of the Waldorf-Astoria, and so on, entertaining mostly well-to-do white audiences. Then the civil rights movement exploded, and black entertainers from a younger generation were joining a big cause. Lena felt left out. She saw the movement as her chance to prove that she really cared.

PM What was the public’s perception of her during the civil rights movement?

JG I don’t think she was seen as a mover-and-shaker, even though she really worked hard for the movement. I don’t know how aware the public was of most of her activity. She did go to the March on Washington in 1963, but made only a momentary appearance before the public, shouting “Freedom!” into the microphone. Still, she made the trip.

PM As the civil rights movement wore on through the mid-1960’s, she became a major supporter of Malcolm X, even calling him her “idol.” Why did Horne relate more to his militant activism than with the nonviolent activism of Martin Luther King Jr.?

JG Because she was angry, and what angrier black man was there at that time than Malcolm X? Martin Luther King was looking for peaceful change, and the idea of peaceful change did not appeal to Lena Horne. She loved the fact that Malcolm X was out for blood, and it really spoke to the rage in her.

PM What was her most important contribution to the civil rights movement?

JG The obvious answer is that she opened so many doors for black actresses in Hollywood. But beyond that, she seldom tolerated racism. In the 1940’s – before the term “civil rights movement” had ever been coined – if a hotel denied her musicians a room and sent them across town, if she was turned away at a restaurant or denied a cup of coffee, it made her mad as hell, and she raised a fuss. These incidents made the papers, and helped open people’s eyes to the fact that no black person was immune to racism; even Lena Horne of M-G-M could be treated like dirt. All the while, she was an image of ultimate class and dignity at a time when the prevailing black image was quite demeaning.

PM Having such a complex career must have taken its toll on her relationship with her children. Was this a lifetime challenge or did she learn to be a good mother as time went on?

JG It was a lifelong challenge, and although she apparently tried to become a better mother as time went on, her son died when he was thirty, and by that time her daughter was a married woman with children of her own. Lena’s career was all-consuming, and it got the bulk of her attention. The children of career-obsessed parents have a tough time.

PM She felt a great sense of accomplishment with her 1981 Broadway production, Lena Horne: The Lady and her Music…

JG The Lady and her Music remains the most successful one-woman show ever to appear on Broadway. A lot of veteran show-business ladies thought that they could do what Lena had done, but of course they couldn’t. Barbara Cook couldn’t pull it off; Peggy Lee did even worse. The year before that show opened, Lena had announced her retirement, as she so often had before. Then came this triumph of a lifetime. Once more, Lena was out there alone, but this time she was free to call all the shots, to depict herself just as she wanted to be perceived. The public saw a long-suffering but emancipated black woman who had triumphed over every societal demon and had finally found peace. She hadn’t. The truth was more between the lines than it was in the script. But that show electrified and inspired a lot of people.

PM In his August 9th 2009 review of your book, the Washington Post critic Jonathan Yardley wrote: “In his introduction he portrays himself as in awe of Horne when he interviewed her for The New York Times in 1994. But you don’t have to read much more to conclude that, to put it as charitably as possible, he doesn’t really like her that much.” Would you agree with that statement?

JG Absolutely not. I haven’t read that review, but of course I heard about it. I encountered the same perception with my Chet Baker book. If you portray an iconic figure honestly, as a warts-and-all human being, as I do in my books, then some readers will think you have it out for your subjects. When I hear Lena’s recordings now, I am more moved by her than ever, because I really understand what lay behind that formidable façade that intimidated a lot of people. Now I know so much about her struggles, about all she had to do to survive, and I respect and admire and enjoy her more than I ever have before. I am very interested in human psychology and the darkest corners of human psychology. A lot of people are afraid of it. But I was utterly fascinated by Lena’s behavior. There were a lot of people she didn’t treat well, including her husband, Lennie Hayton. But she’s an extremely complex personality, and a woman who harbored enormous conflict. And of course, who could reasonably expect such a fiery stage persona to be a nice, normal, easy person offstage? Lena’s performing style grew out of personal turmoil.

PM Have you spoken to Lena Horne since your book was published?

JG I haven’t exchanged a word with her since 1994. She became reclusive in 2000, so as I said, I never had access to her over the course of this book.

I would like to share a personal story with your readers. In 1991, I sent her a copy of my first book, Intimate Nights: The Golden Age of New York Cabaret, along with an invitation to the book’s release party, which took place at the Algonquin Hotel in New York. Wasn’t I a dreamer? One day I went out to buy milk, and when I came back there was a message on my machine from Lena. I still have it. It was lovely and gracious. She congratulated me and said she would not be able to come to the party but wished me the very best. Oh God, imagine how I felt, realizing I had just missed that telephone call! I still have the message. How could I not like that person?

PM What do you think was more important to Lena Horne, her self-image or her own abilities as an entertainer?

JG I couldn’t answer that, because she devoted so much time to both. She wasn’t prententious about her art, but she took it very seriously. She worked so hard to perfect what she did; she wanted to be taken seriously and to earn that attention. But her image was all-important. Walter White, Noble Sissle, and her other early mentors had reminded her that people were watching her very closely, and she couldn’t let them down.

PM What will Lena Horne be most remembered for?

JG She will probably be best remembered for her beauty – it was that overwhelming. When you hear the name Lena Horne, if you have ever seen her at all, her face flashes into your mind. That aside, I think she will be remembered as ultimate class. That’s what she’s been from the time she stepped onto the Cotton Club stage until today.

.

.

photo via Wikimedia Commons

Lena Horne performing on The Bell Telephone Hour television show, 1965

.

“The woman is so stunningly gowned to accent a beautiful figure that this, in itself, would catch an audience’s attention. But the ultimate hypnotic effect is the music, the arrangements and an intensity of delivery that finds its essence in eyes that seem to bore into you.”

– Robert Dana in the New York World-Telegram & Sun, January, 1956

.

.

___

.

.

Stormy Weather: The Life of Lena Horne

by

James Gavin

.

.

About James Gavin

James Gavin has written about some of the most significant black musical figures of our time, including Nina Simone, Harry Belafonte, and Miriam Makeba. His 300+ CD liner note essays include Grammy-nominated article for the box set Ella Fitzgerald: The Legendary Decca Recordings. He is the author of Deep in a Dream: The Long Night of Chet Baker and Intimate Nights: The Golden Age of New York Cabaret.

.

.

___

.

.

Critical Acclaim for Stormy Weather: The Life of Lena Horne

” … James Gavin offers a fascinating study of a complicated woman and the complicated times that shaped her…he delivers a portrait of a very human artist who is as compelling for her foibles as her accomplishments…By crafting a dense, moving tribute that never dissolves into hagiography, Gavin has proven her point.”

– USA Today

.

___

.

“So full of insight into Lena, and the author knows his subject’s work. The critiques of her film appearances and her recordings are dazzling passages of insight all on their own…. Talk about something that keeps you turning pages to the very last, and wishing there was more.”

– Liz Smith

.

___

.

“There is good reason for James Gavin’s Stormy Weather: The Life of Lena Horne to take up – when you count the notes, bibliography, discography, filmography and index – nearly 600 pages. This Lena …has had a life so rich in ups and downs as to make page after page eventful and suspenseful. This all the more so since the book is also two books in one: a thorough and fluent biography and a history of the slow social rise of black people despite crippling discrimination and stinging humiliations a history in which Horne’s story is embedded, notwithstanding some personal jumps ahead.”

— The New York Times

.

___

.

“For most of her life, Lena Horne has been a very angry woman. She may have given as good as she got for many of her 92 years, but as related in James Gavin’s definitive new biography, she had reason enough….The power of Gavin’s biography is that he has clearly labored to separate fact from fiction…Beyond that, she was a complicated woman whose personal struggles with identity were inextricably intertwined with those of African Americans throughout the 20th century. In Gavin’s capable hands, Lena Horne’s story is both uniquely her own and an integral part of a larger cultural journey.”

— San Francisco Chronicle

.

.

___

.

.

This interview took place on September 18th, 2009, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician associate editor Peter Maita

.

.

If you enjoyed this interview, click here to read our interview with James Gavin on Chet Baker.

.

.

___

.

.

Click here to subscribe to the (free) Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter

Click here to help support the continuing publication of Jerry Jazz Musician (thank you!)

.

.

___

.

# Text from publisher.

.

.

.