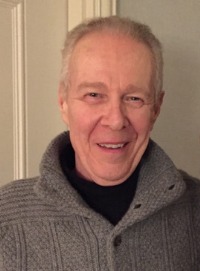

The author in the studios of WHBI

Newark, New Jersey, 1960

_____

Woody n’ Me

by Robert Hecht

I’m driving up Raymond Boulevard toward downtown Newark. In the darkness the huge lighted sign atop the Public Service Electric & Gas Company serves as a beacon for approaching the city. Yet tonight something is off with the sign, and I laugh out loud as I see that its ‘L’ has burned out…and that it is now offering ‘PUBIC SERVICE’ to the community!

I am on my way to work at radio station WHBI where I am a staff announcer but also produce a nightly jazz show. On the car seat next to me is my metal carrying case of LPs, carefully chosen from my collection for playing on tonight’s show.

WHBI’s transmitter is powerful enough to cover the Newark metropolitan area as well as all of Manhattan, so at the tender age of nineteen, for two hours every night, from ten to midnight, I host a show I call ‘Profiles in Jazz,’ that reaches into the homes and cars of many of the New York area’s hardest-core jazz fans. It’s a rather heady experience for a young man.

Newark itself has a large black population with many devoted jazz listeners. After all, this is the city that spawned the likes of Sarah Vaughan and Wayne Shorter, who was known in his early days as ‘The Newark Flash.’

But WHBI’s main commercial mission is to appeal to the black religious community. The station sells airtime to the pastors of numerous local black churches who are hoping to reach a larger audience, and on Sundays the station sends out its team of engineers to do live remote broadcasts from these churches. During the week we play mostly gospel music records, interspersed with sermons by a variety of black preachers, live from our studio.

The Sunday services are often quite rousing, and entertaining. These are predominantly churches of the so-called ‘Holy Roller’ persuasion, many of them merely shabby store-front affairs, where the congregants become very emotionally caught up in the promises of redemption and salvation, participating enthusiastically in the call-and-response exhortations of the ministers.

One of the pastors is my particular favorite, a very colorful and charismatic preacher, who regularly pleads with his parishioners to surrender their lives to Jesus Christ, whom he calls the ‘Boss of the Cross.’ He tells them to come on down to his church, which he calls ‘God’s filling station,’ where you can ‘get your battery recharged and your tank refilled.’

The terrible irony of WHBI is that it is a white-owned and operated station. The only black employee is the office secretary, who looks and, I’m sure, feels quite out of place among the rest of the white staff. All of the on air talent is white.

One day, feeling emboldened after an especially awkward phone call from an irate listener, I suggest to the station manager that it would be a good thing to have some black announcers, especially to handle the gospel segments. Earlier that day I was hosting a gospel music segment featuring such great talents as the Dixie Hummingbirds, the Blind Boys of Alabama, and the Reverend James Cleveland, and things were going along fine until I receive the phone call in the studio.

The man is clearly upset, his voice breaking, as he accusingly demands—

“Are you white??!!”

Like, what in the world is a white guy doing talking about the Blind Boys of Alabama on the radio airwaves?

I am mortified and I apologize to the man for offending him, but what can I say? That I work for a racist radio station? That I know it’s wrong but I work here anyway?

He slams down the phone in disgust. Afterwards, I am terribly shaken by the call and report it to the manager. It’s then that I make the suggestion about hiring some black announcers.

“I’d rather keep them,” he says, looking toward the double-paned wall between the control room and the studio, “on the other side of the glass!”

The next month, however, the station’s owner—perhaps fearing some possible serious backlash—does begrudgingly hire one young black announcer to cover some of the gospel shows.

But tonight, in the summer of 1960, some eight years before the city would break out into flames during some of the worst riots in civil rights history, my mind is only on my jazz show. I park my old jalopy, enter the lobby of the Raymond Commerce Building and take the elevator up to the 32nd floor where the small station is housed.

In the control room of the station there is a window overlooking all of downtown Newark. Sometimes when I am alone at the station late at night I will open that window and smoke a joint while staring down from on high at the twinkling lights of the city spreading out far below.

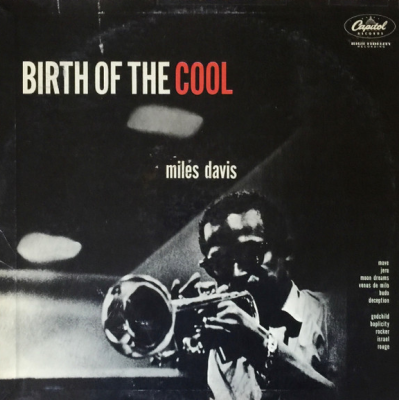

But tonight I get straight to work, if you can call playing the music you adore work. I take the handoff from the staff announcer of the preceding segment and launch into ‘Profiles in Jazz.’ Tonight I am featuring the music of the great modern jazz trumpeter Clifford Brown. I actually get paid for this, I reflect, as I announce the personnel on the first few tracks I’ve been playing, and then tell my listeners to get ready, that it’s time for our weekly jazz contest.

Each week I run a contest in which I challenge listeners to identify something specific about a record I play: sometimes it might be a soloist, other times a composer or perhaps the title of a composition.

For tonight’s contest I am spinning a Randy Weston record. It’s an obscure though relatively recent album by the pianist recorded live at the Five Spot in New York, and it features a special guest artist on the tenor sax. I have challenged my listeners to name that tenor soloist. The first person to call in and correctly give the name wins a newly released jazz album. (This costs me nothing as I receive lots of new releases from all the major jazz record labels as promotional copies and I use the ones I don’t want to keep for myself as contest bait.)

The phone starts ringing off the hook. We have four lines and they are all lighting up. The first few callers guess wrong.

“Dexter Gordon?”

“No, sorry, but thanks for calling.”

“Is it Ben Webster?”

“Close, but no cigar—thanks for calling.”

“That must be John Coltrane, right?’’

“No, but thanks for calling ‘Profiles in Jazz.’”

Then another caller, no question this time—just a bold, declarative statement:

“That’s Coleman Hawkins…Was I first?”

The caller sounds pretty young, like in his teens, and black, and he certainly knows his Coleman Hawkins, even when, as is the case with this record, he is playing in an unusually modernistic setting. I write down his name and address and tell him the album will go out the next day.

And then as the record ends, I inform my audience that a young man from Newark by the name of Woody has correctly identified the big tenor sound of ‘The Hawk.’

The following week I do another contest. This one is more difficult, more esoteric. I ask my audience to see if they can name the trumpeter who plays the short introduction to Sarah Vaughan’s version of the classic Tadd Dameron ballad “If You Could See Me Now.” It’s just a few bars of trumpet but it makes a memorable statement.

I start the record. The trumpet is glorious. A big, clear-as-a-bell sound, full of confidence and passion. It’s Freddie Webster, a man hardly known after his early death in 1947 at the age of 30, a man who didn’t record anything as a leader and whose remarkable sound can be heard on only a small handful of recordings. But Miles Davis has talked about what an important influence Webster was on his early development.

Within seconds of Webster’s brief solo the first line flashes and I pick it up.

“That’s Freddie Webster!” the young caller says excitedly.

“Well, young man, you’ve got some good ears there and you’re the first caller. What’s your name?”

“Oh this is Woody again, I won last week, too.”

“You’re on a roll, Woody!”

“Yeah, well I’m a trumpet player, too, and someday I’m going to be a professional jazz musician.”

I answer the remaining contest callers but no one else correctly identifies Freddie Webster.

The same thing happens the next week.

This one is even more obscure. I play a 1957 track by trumpeter Kenny Dorham that features Sonny Rollins. It’s the standard “My Old Flame,” and in Rollins’ solo he plays a lick that in just a couple of years would become the basis for a John Coltrane composition he called “Like Sonny.” I ask my listeners to name the Coltrane tune. I figure no one, not even that kid Woody, is going to get this one.

For a minute or so after Sonny’s solo no one calls. Then line one lights up.

“‘Like Sonny,” Woody says.

This goes on week after week, with Woody being by far the most frequent winner of the contests.

*******

It wouldn’t be until a few years later that I figure it out, that it all makes sense. It’s when I first hear a Woody Shaw record and learn about his background. Shaw was a dazzling and important hard bop trumpet player, who by his early twenties had incorporated many of the lessons of Clifford Brown, Lee Morgan, Freddie Hubbard, Booker Little and Miles Davis, and developed them into a highly individual, blazingly masterful style of his own.

Yes, that was the very same Woody, from Newark, New Jersey—who as a highly knowledgeable teenaged jazz fan and fledgling trumpet player several years before was the contest champ of ‘Profiles in Jazz.’

Sadly, I never had the opportunity to meet Shaw or to hear him play live. He died as the consequence of a serious drug problem at the age of 44 in 1989. I really wish I’d met him…I would have enjoyed reminding Woody of all those free records he won from listening to my show as a teenager back in his home town.

_____

Robert Hecht is an award-winning jazz disc jockey and fine art photographer whose photo work has been published in LensWork, Black & White, Zyzzyva and The Sun and exhibited internationally. His writing has previously appeared in LensWork and in the haiku journals Frogpond, Bottle Rockets and Modern Haiku. He and his wife live in Portland, Oregon. For twenty-five years they have been partners in On Point Productions, writing and producing marketing and training video programs. Visit his website by clicking here.

*

Have a memorable jazz story you would like to share? Submit it for consideration at [email protected]

Thanks for a warm story about Woody Shaw, a fine trumpeter who died too young

Thanks for a warm story about Woody Shaw, a fine trumpeter who died too young