.

.

“Strange Fruit” was a short-listed entry in our recently concluded 69th Short Fiction Contest, and is published with the consent of the author.

.

.

___

.

.

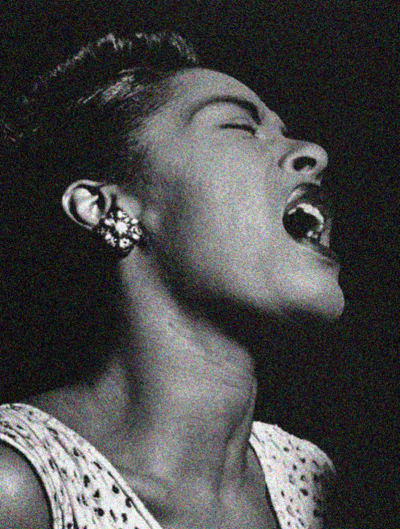

photo by William Gottlieb/Library of Congress (adapted by JJM)

.

.

Strange Fruit

By Stephen Jackson

.

…..The plates feel heavier tonight. Each one Tommy lifts from the tables weighs like Mississippi mud between his fingers, sticky with grease and guilt he can’t name. He stacks them careful—white porcelain against white porcelain—the way Mama taught him back in Tupelo. Keep things in their place, Tommy. Everything’s got its place.

…..But nothing’s in its place down here in this basement. Not the Negro woman singing at the microphone, not the white folks sitting next to colored folks like it’s natural as breathing, not the way his hands shake when he clears Table Seven where a Jewish man argues politics with a Negro professor like they’re equals.

…..Sweet Caroline walks down by the riverside, Tommy hums under his breath, trying to drown out the wrongness. His own song, the one he’s been working on for months. Simple melody, simple words. The kind of thing that might get picked up by one of those Tin Pan Alley publishers if he could just get someone to listen. Sweet Caroline with her hair so fine, dancing in the summer sunshine.

…..Vapid. The word comes from nowhere, lands in his chest like a punch. Where’d that come from?

…..He dumps the plates in the kitchen, watches Josephson through the service window. The owner’s talking to some Negro man in a suit, both of them serious as undertakers. The Negro’s got sheet music in his hands, and Josephson keeps shaking his head.

…..“Strange stuff,” mutters Eddie, the other busboy, sliding past with a tray of drinks. “Owner’s got them singing all kinds of strange stuff tonight.”

…..Tommy knows about strange. Strange is this whole place—this Café Society with its murals mocking rich folks, its Communist meetings in the back room, its Negro performers treated like they’re somebody important. Strange is how he feels when he watches Billie Holiday smoke cigarettes between sets, the way she holds herself like she owns every inch of air around her.

…..He shouldn’t be here. Told Josephson he was sick, tried to get out of working tonight. But the man had looked at him with those sharp eyes and said, “You work tonight or you don’t work nowhere, Mississippi.”

…..How’d he know? Tommy’d never said where he was from.

…..Holiday’s been singing for an hour already. Started with “What a Little Moonlight Can Do,” then moved through “Them There Eyes,” “I Cried for You,” each song drawing the crowd deeper under her spell. During the break between sets, Tommy watched her smoke a cigarette by the kitchen door, that distant look in her eyes like she was seeing something the rest of them couldn’t.

…..Now she’s back for the second set. The crowd’s different tonight. Restless. He can feel it in the way conversations stop when he approaches tables, the way eyes follow him as he moves through the narrow spaces between chairs. Word’s gotten around about what comes at the end of her performance these days. The ceiling presses down, low enough that tall men have to duck under the hanging lights. Everything here feels underground, hidden, like secrets told in root cellars.

…..Sweet Caroline walks down by—

…..“Boy.”

…..Tommy turns. Table Twelve. White couple, well-dressed. They arrived late, during Holiday’s rendition of “Easy Living.” The woman’s got diamonds at her throat that catch the light like ice. The man’s in evening clothes, but his face is hard, northern hard.

…..“Yes sir?”

…..“When does she sing the normal stuff?” The man’s voice carries that familiar edge Tommy knows from home. The edge that means I know exactly what I’m saying.

…..“Sir?”

…..“Real jazz. Standards. Not this…” He waves his hand toward the stage where Holiday’s just finished “I Can’t Get Started.” “We heard she’s been doing some kind of political number.”

…..Tommy’s mouth goes dry. He glances toward Holiday, sees her watching, that knowing look in her eyes like she’s heard this conversation a thousand times before.

…..“I… I don’t know the program, sir.”

…..The woman leans forward. “We heard this was supposed to be… authentic. But this integration business…” She makes it sound like a dirty word. “We didn’t know.”

…..Tommy nods, feels that familiar comfort of agreement settling into his bones. These people understand. These people know how things should be.

…..But then he looks at Holiday again, really looks, and something shifts in his chest. She’s not performing right now, not putting on any show. She’s just a woman getting ready to sing, and there’s something in the set of her shoulders that reminds him of his mother when she was about to do something that scared her.

…..“I’ll… I’ll ask about the program,” he manages.

…..As he moves away from the table, their conversation follows him:

…..“Should have gone to the Cotton Club.”

…..“At least there they know their place.”

…..Their place. The words echo in Tommy’s head as he clears glasses, as he refills water, as he tries to disappear into the rhythm of work. But his own song won’t come now. Every time he starts humming Sweet Caroline, the melody crumbles, sounds thin as tissue paper.

…..The room’s filling up even more for the second set. More white faces, more colored faces, sitting together like it’s the most natural thing in the world. Like Mississippi never happened. Like rope and fire and midnight riders are just stories somebody made up.

…..But they’re not stories. Tommy knows they’re not stories because he was there last summer when they dragged Willie Jackson out of his cell and—

…..Don’t think about that. Don’t think about Willie’s eyes.

…..He dumps another load of glasses in the kitchen, comes back out to find Holiday warming up for what everyone knows will be the final song of the evening. She’s moved through “Body and Soul,” “I’ll Never Be the Same,” each number more intimate than the last. The conversations are dying down now, that expectant hush settling over the room like dust over everything. There’s something different about her tonight as she approaches the microphone one last time. Something that makes the air feel thick, hard to breathe.

…..People know what’s coming. Some lean forward. Others—like the white couple at Table Twelve—are gathering their things, preparing to leave before the final number begins.

…..“This next one,” she says, her voice carrying that rasp that makes every word sound like it’s been through fire, “this next one’s a little different.”

…..Tommy’s clearing Table Six when he sees it—the white couple from Table Twelve gathering their things. The woman’s purse, the man’s hat. They’re leaving, and from their faces, they know something’s coming they don’t want to hear.

…..What do they know that I don’t?

…..Then Josephson appears out of nowhere, moving through the room like a general before battle. He stops at each table where staff is working, says something quiet, urgent. When he reaches Tommy, his words are sharp as glass:

…..“Stop everything. Now. Don’t move during the song. Don’t breathe loud. You understand me, Mississippi?”

…..Tommy nods, but his hands are shaking now, the bus tub balanced against his hip feeling like it might fall any second. Around the room, other waiters and busboys are freezing in place, like they’re playing some children’s game.

…..What kind of song stops a whole room?

…..The lights go down. Every bulb in the room clicks off—the table lamps, the bar lights, the dim fixtures along the walls—until there’s nothing but darkness and the sound of breathing. Then a single spotlight cuts through the black, tight and focused, illuminating only Holiday’s face and maybe the curve of her shoulder. In that small circle of light, her voice begins, soft as a whisper:

…..“Southern trees bear a strange fruit…”

…..Tommy’s never heard anything like it. Not the melody—that’s simple enough, plain as morning coffee. It’s the words. The way she shapes them, like each one costs her something to say. And as she keeps singing, as the images pile up in the darkness—blood on leaves, blood at the root—Tommy feels something breaking apart inside his chest.

…..Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze…

…..Willie Jackson. Willie Jackson swinging from the old oak behind the courthouse, and Tommy was there, Tommy was in the crowd, Tommy said nothing when they lit the fire, did nothing when Willie’s eyes found his in that last moment before—

…..Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.

…..The white couple from Table Twelve. They’re gone. Tommy can hear their footsteps on the stairs, the woman’s heels clicking against the wood in quick, angry rhythm. They knew. They knew what was coming and they ran.

…..But Tommy can’t run. He’s frozen here with a bus tub full of dirty dishes, forced to listen as Holiday tears open every comfortable lie he’s ever told himself about home, about Mississippi, about the way things are supposed to be.

…..Here is a fruit for the crows to pluck…

…..Willie’s mother screaming. Tommy remembers that now, though he’s spent months trying to forget. How she screamed Willie’s name until her voice broke, until the men told her to shut up or join him.

…..For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck…

…..Tommy was seventeen then. Old enough to know. Old enough to speak. Old enough to walk away before it started, or stay and try to stop it, or at least—at least not cheer when the rope went tight.

…..But he did cheer. God help him, he cheered.

…..For the sun to rot, for the trees to drop…

…..The song’s building now, Holiday’s voice climbing like it’s reaching for something beyond the basement ceiling, beyond the streets of Greenwich Village, beyond everything safe and contained about this moment. And Tommy realizes he’s crying—not the easy tears of a sad song, but the hard, angry tears of someone discovering they’ve been lied to their whole life.

…..Here is a strange and bitter crop.

…..The spotlight cuts out. Darkness. Complete and total darkness, and in that darkness, Tommy hears his own breathing, ragged and desperate. Around him, the silence stretches like a held breath, like the moment before Willie’s mother started screaming.

…..Then one person starts clapping. Slow, deliberate claps that echo off the low ceiling. Then another. Then suddenly the room explodes with applause—not the polite kind, but something deeper, more desperate, like people trying to applaud away the truth of what they’ve just heard.

…..When the lights come up, Holiday’s gone. The stage is empty. And Tommy’s standing there with a bus tub full of dishes, tears on his face, everything he thought he knew about music, about himself, about the price of silence, lying in pieces around his feet.

…..Sweet Caroline walks down by the riverside…

…..The words come automatically, but they taste like ash now. Like burnt paper. Like lies he’s been telling himself about what songs are supposed to do, what they’re supposed to say.

…..A Negro man at Table Four—the professor he’d seen earlier—catches his eye. The man’s face is wet too, but there’s something else there. Something like recognition.

…..“You hear that, son?” the man asks quietly. “You really hear it?”

…..Tommy can’t speak. Can only nod as he sets down the bus tub, as his hands finally stop shaking, as something new and terrible and necessary settles into the place where his comfortable ignorance used to live.

…..He hears it. God help him, he finally hears it.

…..And tomorrow—tomorrow he’s going to find musicians who know what Holiday knows, who understand that songs aren’t just pretty sounds to fill empty air. Tomorrow he’s going to learn how to tell the truth with music, even if it hurts. Especially if it hurts.

…..Because some fruit is too strange, too bitter, to let rot in silence.

…..The professor nods, like he can read Tommy’s thoughts, like he’s seen this transformation before in other young white faces stunned by unexpected truth.

…..“That’s how it starts,” he says. “That’s how everything starts.”

…..Tommy picks up his bus tub and moves toward the kitchen, but he’s different now. Heavier. Lighter. Broken and healing all at once. Behind him, the conversations are starting up again, but they’re different too—quieter, more careful, like people trying to rebuild something that got torn down.

…..In the kitchen, Eddie’s washing glasses with unusual focus.

…..“Some song,” Eddie says without looking up.

…..“Yeah,” Tommy manages. “Some song.”

…..But it wasn’t just a song. Songs are safe things, pretty things, things that don’t change you. What happened out there was something else entirely. What happened was the sound of America telling the truth about itself, whether it wanted to hear it or not.

…..And now Tommy’s heard it. Now he knows.

…..Now everything has to be different.

.

.

_____

.

.

Stephen Jackson is a writer, musician, and educator living on the border between the United States and Mexico. His work frequently explores the liminality of spaces, systems of belief, and interactions between the sacred and secular. Past works have been published in Black Fox Literary Journal, The International Human Rights Arts Movement Literary Magazine, Eternal Haunted Summer, Miserere Review, and anthologized in the collections Bayou, Blues and Red Clay, Dawn Horizons, and Ghosts Echoes and Shadows. His first book of short stories, Spring Variations was published in February 2025.

.

.

Listen to the 1956 recording of Billie Holiday singing the Abel Meeropol (a.k.a. “Lewis Allan”) composition “Strange Fruit.” Charlie Shavers is the trumpeter. [Billie Holiday]

.

.

Click here to watch a 1959 film of Billie Holiday performing “Strange Fruit”

.

.

___

.

.

Click here to help support the continuing publication of Jerry Jazz Musician, and to keep it ad and commercial-free (thank you!)

.

Click here to read “My Vertical Landscape,” Felicia A. Rivers’ winning story in the 69th Jerry Jazz Musician Short Fiction Contest

Click here to read more short fiction published on Jerry Jazz Musician

Click here to read The Sunday Poem

Click here for information about how to submit your poetry or short fiction

Click here for details about the upcoming 69th Jerry Jazz Musician Short Fiction Contest

Click here to subscribe to the Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter (it’s free)

.

.

.

___

.

.

Jerry Jazz Musician…human produced since 1999

.

.

.

Damn! I’m reading this with all kinds of mixed emotions. I coulda been Tommy back in the 50s. My stomach churned watching him get pulled into that inescapable moment knowing that he’s either doomed or saved by what comes next. I feel like the author picked me up and forced me to watch this like a film or a traffic accident – whatever it is, I couldn’t look away. Thanks for sharing it!