.

.

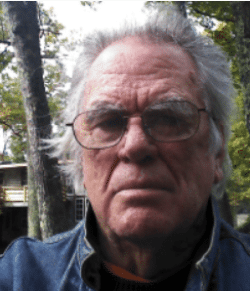

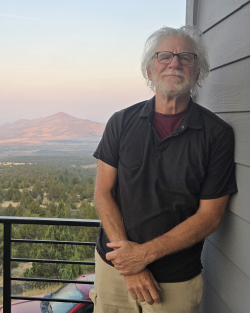

Tad Richards, author of Listening to Prestige: Chronicling its Classic Jazz Recordings, 1949 – 1972. [SUNY Press]

.

.

_____

.

.

…..Many of us are jazz record collectors – freaks, even. We troll record bins and imagine the sound of the music embedded in the vinyl. There is deep love for the music, and, of course, our obsession with finding that one obscure recording by Sonny Stitt or Sarah Vaughan or Ben Webster that will augment the collection.

…..As we go through this process, we learn record labels and flock to those who’ve earned our trust – major labels, sure, but the spirit and risk-taking of the artists recording for independents like Savoy, Dial, Verve, Contemporary, and, of course, Blue Note likely fostered a more permanent enthusiasm for the music.

…..One of those labels, Prestige, was founded in the late 1940’s after 18-year-old Bob Weinstock was introduced to the music of pianist Thelonious Monk by one of his early mentors, Blue Note’s co-founder Alfred Lion. This fascination with Monk became the foundation of Weinstock’s desire to record modern jazz, and to do so on his own label.

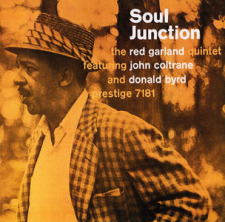

…..In Listening to Prestige: Chronicling its Classic Jazz Recordings, 1949 – 1972, the enthusiast and historian Tad Richards has written a long overdue musical history of Prestige. A passionate consumer of its many recordings since his initial listening to the 1958 session showcasing an emerging John Coltrane with the Red Garland Trio, Richards draws readers into stories involving its visionary founder, the classic recording sessions he assembled, and the brilliant jazz musicians whose work on Prestige helped shape the direction of post-war music.

…..Richards’ talents as a writer, his ears for the music, and a touch of his personal history with Prestige make this an enjoyable and essential read for fans of jazz and its immense cultural impact. .

…..He discusses his book – scheduled for publication in January, 2026 – in this June, 2025 interview.

Joe Maita

Editor/Publisher

.

.

Readers can click on links within the interview to listen to songs on Youtube referred to during the conversation.

.

.

_____

.

.

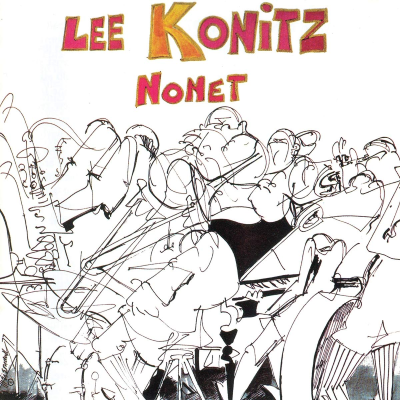

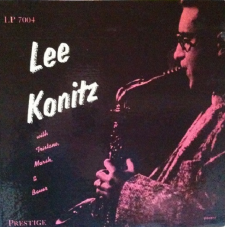

“There was precious little modern jazz being recorded by anyone when Bob Weinstock decided to start a label. He was encouraged by bebop pioneer Kenny Clarke, who was a regular at Winstock’s [record] store and had gotten to be friends with the young man. Clarke told him he could get him all the stars of bebop he could handle. On January 11, 1949, Weinstock entered the studio with a quintet led by Lennie Tristano (with alto saxophonist Lee Konitz) for his first step on the venture that was to be his legacy: recording this new jazz.”

-Tad Richards

.

.

Listen to the 1949 recording of Lee Konitz performing his composition “Subconscious-Lee,” with Konitz (alto saxophone); Lennie Tristano (piano); Billy Bauer (guitar); Arnold Fishkin (bass); and Shelly Manne (drums). This was the first record released by Bob Weinstock, under the “New Jazz” label (which preceded Prestige). [Universal Music Group}

.

.

JJM You wrote that the John Coltrane session with the Red Garland Trio is one that changed your life. What was your experience with that record?

TR I was 18 when I first heard this, in college, and in love with rhythm and blues. Until then I had never really listened to jazz at all. It was the middle of the night and I’d just come home from a college neighborhood bar. I turned on the radio looking for a rhythm and blues station and became transfixed by what I was hearing. I recall standing in the middle of my room staring at the radio because I had never heard anything like this before. The music went right through me. I learned that it was this John Coltrane album, which hit me so hard that I started listening to jazz. It turned out that this particular album was on Prestige, and of the next three jazz albums I purchased, two were on Prestige – the first Mose Allison album, and the King Pleasure/Annie Ross record. The third was a Gerry Mulligan/Chet Baker album on World Pacific.

JJM So the music of Prestige was foundational to your jazz listening…

TR Yes, and it was during a conversation I was having with my friend Peter Jones about 15 years ago about the rock, rhythm and blues, and top 40 music we listened to in the 1950’s – much of which was good, much of which was awful – that I was reminded that all of the jazz we listened to during that era was good music. There seemed to be a steady stream of incredible music. That’s when I decided to test that out and go back and listen to everything and see if it was really all that good. And since so many of the records I bought during that era were on Prestige, I wanted to go back and re-listen to everything recorded on that label and test my theory that everything was “good.” I started my “Listening to Prestige“ blog, and when I was approached by the SUNY editor Richard Carlin about doing another book after Jazz With a Beat, I suggested doing a history of Prestige Records. So, that is how this book came about.

JJM So, your book focuses on the musical history of Prestige without getting into founder Bob Weinstock’s complex history as a businessman, or how he related to the musicians he recorded. Why did you choose to stay away from that?

TR I made that choice because I’m not that kind of historian or scholar or busybody. I did address some of this history in the book, but not very much. Some people have said that Weinstock was a corrupt businessman who exploited those who worked for him, but others say that he was actually a decent guy. For example, in his autobiography Miles Davis said that while Weinstock didn’t pay him enough, other than that he didn’t have anything bad to say about him. So, while I understand there is controversy, it is not my controversy. I didn’t really care about that aspect of the history of Prestige.

Prestige Records founder Bob Weinstock

JJM Did you get a sense that artists working for Prestige were at least getting paid as much as other independent jazz labels like Blue Note or Contemporary or Savoy were paying?

TR Savoy was owned by Herman Lubinsky, who was a total crook. So, certainly Weinstock was better than that. Blue Note, on the other hand, was the gold standard of the independent jazz labels in terms of integrity and pay. But the record business was tough, and all of the labels chiseled a little bit.

Weinstock was a kid when he started Prestige. He was a 19-year-old who had a love for jazz, and he eventually became a successful businessman in an industry where there was a lot of dishonesty and exploitation of musicians. My impression – which isn’t based on any serious research – is that his label was better than others at the time, or at least no worse.

JJM I also possess an appreciation for the label, and when you are a kid buying great jazz records you don’t think about how much musicians are getting paid or if they are high while in the studio. But I ultimately discovered that Prestige became known as the “junkies label” for a reason.

TR And I don’t shy away from that, it just isn’t the main focus of this book. Some people criticize Weinstock for hiring addicts because it was easier to pay them less, but Miles Davis, not a generous man with compliments, says in his autobiography that he’s grateful to Weinstock for taking a chance on him when he was still addicted.

JJM Who was Bob Weinstock at age 19 when he began this label?

TR His father was in the garment business, and he tells stories about going shopping at the flea markets with his father and buying tons of 78 RPM records for 10 cents apiece. So, he started collecting records early in life. At age 15 he started a used jazz records mail order business, and at 18 his father set him up in a storefront on Times Square selling records right near the Metropole Café jazz club. At the time, he was listening to the kind of music his father listened to, which was old time New Orleans jazz. This was in 1948, during the time of the New Orleans jazz revival. Then, the famous story is that Alfred Lion of Blue Note dropped by the store one day and tells them they have to listen to an album – which was his Thelonious Monk record. Weinstock flipped out over it and was absolutely converted to bebop to the point he wanted to start his own label so he could record this music.

Because his store was right next to the Metropole Cafe, and since he was also hanging out at the Royal Roost, he was able to meet a lot of jazz people. One of the musicians he meets is Lee Konitz, who Weinstock expresses his interest in starting a label to but is unsure about who to record. Konitz says “Me!” So, the first record they do on the New Jazz label – prior to Prestige – was “Subconcious-Lee![]() ” with Lennie Tristano’s Quintet, which Konitz was part of. After that he goes from recording Tristano, who was one of jazz music’s most inaccessible musicians, to one of its most accessible, Stan Getz, who happened to be in town playing with Woody Herman, likely at the Metropole. This gave Weinstock access to all of Herman’s musicians, and he records Terry Gibbs and Serge Chaloff and Getz and all the other Herman guys, and that turns out to be the beginning of the label.

” with Lennie Tristano’s Quintet, which Konitz was part of. After that he goes from recording Tristano, who was one of jazz music’s most inaccessible musicians, to one of its most accessible, Stan Getz, who happened to be in town playing with Woody Herman, likely at the Metropole. This gave Weinstock access to all of Herman’s musicians, and he records Terry Gibbs and Serge Chaloff and Getz and all the other Herman guys, and that turns out to be the beginning of the label.

It’s interesting to see how focused Weinstock was, right from the beginning. If you look at the first two years of Atlantic Records, they are all over the map – I can’t even begin to tell you all of the weird stuff they were recording. They eventually settled on the Joe Morris Orchestra backing up the likes of Ray Charles and Lowell Fulson, which set them off on the rhythm and blues path. But Weinstock knew exactly what he wanted, and went after it.

JJM What did he want?

TR He wanted to record bebop, the modern music of the time.

JJM Yet one of his earliest recordings was of the New Orleans cornetist Jimmy McPartland…

TR McPartland was an outlier, the one Dixieland musician he recorded.

JJM Ok, but I guess my question is did he have a vision for his label to record bebop and modern musicians like Tristano, or, using McPartland and Serge Chaloff, as an example, to simply record anyone he had access to in order to launch the label?

TR Probably a little of both. Hearing Monk is what set off his enthusiasm, but he was just a kid, learning how to go about the business of music and recording it. He talked about who he’d like to record, but most of the early people were the Woody Herman guys, like Chaloff. What he really wanted to do was record Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, but those guys were taken.

JJM I know your book focuses on jazz, but it is interesting that as you go through the Prestige catalog and see the artists who recorded for the label, it is easy to conclude that from the outset Weinstock recognized the importance of having a diverse roster of talent…

King Pleasure

.

H-Bomb Ferguson

TR Yes, he recorded rhythm and blues artists like H-Bomb Ferguson and King Pleasure, who was actually an R&B artist before recording “Parker’s Mood” with top jazz musicians. But Weinstock never did very well recording music other than jazz. Since rhythm and blues was a more popular form of music than jazz, you’d think he would have had more success with it, and maybe he did because in one interview he said that Ferguson was one of his biggest sellers. But I find it strange that he didn’t seem to have an interest in following up a huge hit like “Moody’s Mood” – it would have been understandable had he made an attempt to milk that for all he could – but his recordings of King Pleasure after that were few and scattered. So, it’s evident that he didn’t invest the money he made from King Pleasure’s recordings into more of that kind of music; instead, he invested it in signing Monk and other modern jazz musicians, which is interesting and admirable.

JJM He had a much different approach to the recording session than Blue Note did…

TR Yes. I find it interesting how the collectable value of a Blue Note record is much higher than those of Prestige, and I believe one of the reasons for that is that Weinstock’s approach to making music is not very highly regarded among today’s collectors. A reason for this may be because he valued the spontaneity of the jam session and took a no rehearsal approach to it, and there are very few alternate takes from these sessions. Today what seems to be valued is perfection, and Prestige’s recordings are not perfect, but they are important because they capture a time in jazz history.

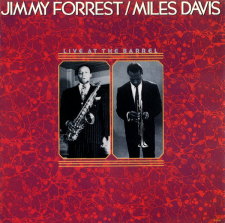

Jimmy Forrest/Miles Davis, Live at the Barrel

What’s New![]() is from the album

is from the album

One example of this…In my book, I write about Miles Davis and how Weinstock had given him a chance to record even when he was dealing with addiction. At one performance in the Midwest he played with Jimmy Forrest at a club in St. Louis, which Prestige released as “Live at the Barrel.” This record was treated condescendingly by the contemporary critics, but I loved it because it was the real thing – American music from the heartland, recorded live by musicians who were actually out there playing in clubs in a city like St. Louis. It’s jazz in the night!

Four of the contractual obligation albums

Walkin’ |

Cookin’ |

Relaxin’ |

Steamin’ |

The last sessions Miles recorded for Prestige came in 1956 – the contractual sessions that came about after Miles signed with Columbia, who couldn’t release any new recordings until after he fulfilled his obligation to Prestige. So, he recorded five albums worth of music for Prestige in marathon sessions – a dozen or so recordings at a time, only one take per tune – while also recording the album ‘Round Midnight for Columbia under the guidance of major label producers like Teo Macero and George Avakian. The Columbia sessions are rehearsed, and multiple takes are recorded and spliced, resulting in a perfect recording of a modern album that is now considered to be one of his greatest. The Prestige recordings, on the other hand, are now considered by many younger critics as sloppy and not all that great, and that is because in today’s world, perfection is prized. But back then, spontaneity was prized, and if you read the reviews from that time the Prestige sessions were much more highly regarded than the Columbia sessions.

JJM Weinstock is credited for helping revive Miles’s career, taking him on as an artist after Capitol cut him loose, which ultimately led to Columbia taking notice of him at Newport in 1956…

TR That’s right. He had left New York and nobody really knew where he was, but Weinstock tracked him down in St. Louis and brought him back to New York, where he relaunched his career.

JJM In addition to Miles, other modern jazz giants of the era who recorded for Prestige included Monk, the Modern Jazz Quartet, John Coltrane, and Sonny Rollins.

Prestige albums by Monk, the MJQ, John Coltrane, and Sonny Rollins,

|

Monk 1956 |

Django 1956 |

|

Coltrane 1957 |

Saxophone Colossus 1956 |

TR Yes. The MJQ is particularly interesting because everything Weinstock and Prestige became famous for – jam sessions with no rehearsals or alternate takes – goes against what the MJQ was about. And, in fact, it is not clear that Weinstock was crazy about them. Who he was crazy about was Milt Jackson, and what he wanted to do was record Milt with Horace Silver, but Milt told Weinstock that if you want me, you also get John Lewis, although in 1955 he did pair Horace and Milt together.

JJM There were internal creative challenges within the band, but the MJQ were a financial success for Prestige. Was their move from Prestige to Atlantic in 1956 all about the money?

TR Money was a factor, sure, but it also had to do with the fact that there was never a meeting of the minds between Weinstock and John Lewis.

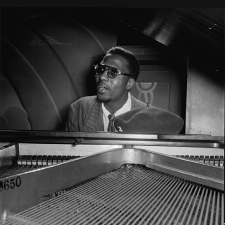

JJM What were the risks for Prestige in signing Monk in 1952?

William Gottlieb/Library of Congress

Thelonious Monk, 1947

TR No one was interested in Monk at the time. Today he is considered one of the greatest jazz musicians and composers, but If you look at the Downbeat jazz polls from then he isn’t even mentioned as a composer, and only occasionally as a pianist. While Blue Note loved him, they let him go because he didn’t sell any records, and ultimately his Prestige records didn’t sell either. So, he didn’t make money directly from the sale of Monk’s records, but he made money from having Monk in his catalog, when he sold the label to Fantasy Records in 1971.

JJM At the time Weinstock signed Monk to Prestige he had just lost his cabaret card, banning him from playing clubs in New York. So, this had to have presented Prestige with an enormous challenge since Monk couldn’t go out and promote his own records.

TR Exactly, which is why you have to give Weinstock a lot of credit for recording the people he liked. He was always taking chances on musicians who didn’t have a name, and one reason is because when you are a small, independent label without very much money you can only afford the guys who are just coming up, and they would turn out to be generational musicians like Miles Davis or Sonny Rollins or Eric Dolphy.

JJM He had a philosophy about not letting a sideman lead his own session right off the bat…

TR Yes. He tended to hire musicians he’d heard playing with other leaders, and part of the reason for that is, as we know, Weinstock was not much of a talent scout. He didn’t go out to the small clubs in the out-of-the-way places. But he signed Sonny Rollins after he played with Miles.

JJM Miles was sort of a talent scout for him. If musicians played with Miles, it meant a lot to Weinstock…

TR Yes. Rollins, John Coltrane, and Red Garland all played with Miles and recorded as leaders for Prestige. Garland recorded a ton of albums for Prestige, and while Coltrane was the caviar of the label, Red Garland was its bread and butter.

JJM Yes, so the stars of the label weren’t necessarily the biggest income producers for it. Who are some of the artists who brought major revenue to Prestige?

TR The big ones were King Pleasure, “Moody’s Mood for Love” The organist Richard “Groove” Holmes had a huge hit with “Misty”. And I’m sure he did pretty well with Miles, because as we discussed earlier, even though he was considered washed up when Prestige signed him, the albums recorded during those marathon sessions – “Cookin’,” “Workin’,” “Relaxin’,” “Steamin’” – sold very well over the years. And they recorded so much Coltrane that even years after he left the label they were still releasing his albums.

JJM So as the likes of Miles and Coltrane and Monk the MJQ went off to other labels, the Prestige catalog became much more valuable…

TR Absolutely. Other than the MJQ, who were good self-promoters, I don’t think he made much money off these artists while they recorded for the label. But when he sold the catalog it was so valuable because of the smart decisions he had made that were based on the quality of the music, rather than on whether or not his artists would record contemporary hits. So, his catalog was golden.

Rudy Van Gelder

JJM One of the things that Prestige shared in common with Blue Note was that they both utilized the work of the sound engineer Rudy van Gelder, who recorded nearly all of Prestige’s records after the James Moody album, Moody’s Moods. And he was also, of course, on virtually every Blue Note session. Was there any difference in the way he worked with these labels?

TR I don’t believe so. He was only interested in the music and the sound coming from his studio. When Weinstock asked him what he did to make the sound so incredible, Van Gelder told him that it was none of his fucking business. The important thing is that you like it. There’s even an unverified story that Van Gelder used to put fake microphones around the studio so nobody would know which the real ones were.

JJM Having a background in the record business, I am always interested in how labels marketed their product. As a fan I’d love to go into stores and flip through records and “feel” the music with my fingers and “hear” the music with my eyes, if that makes sense. So, album covers were, and still are, critical to the success of a label. In 1952, Weinstock commissioned David X. Young to do the cover of a Jimmy Raney LP, which you describe as being a significant event in the label’s history…

TR Yes. Weinstock was a little late to the party when it comes to album cover art. Blue Note was already producing beautiful album covers, but Prestige was not until they hired Young – who was part of the Jazz Loft with the photographer Eugene Smith – and a few other designers. So, Blue Note were the innovators of album cover design and have that part of jazz history pretty much in their corner. There is a coffee table book of Prestige album covers that feature many beautiful covers, but it was clearly an imitation of something Blue Note had already done.

JJM I was just revisiting some Prestige covers, and there are so many memorable designs. For example, all four of the Miles marathon session albums have unique, interesting covers. Is there a Prestige cover that stands out for you?

TR The John Coltrane album with the Red Garland trio we talked about earlier has a beautiful red and black abstract design. I’ve always loved that one.

JJM What was Prestige’s role in the expansion of interest in jazz music during the 1950’s?

TR They played a pretty important role, and we wouldn’t have jazz as we know it without them, and without Blue Note, Riverside, and New York’s independent labels. It is as simple as that. If you had to rely on Columbia, RCA and Decca, so many great musicians would have gone unrecorded. Weinstock said that Prestige was like a farm team, and that’s true. They recorded great artists who then went on to major labels. Who would have recorded artists like Art Farmer, Gigi Gryce and Wardell Gray if it weren’t for pioneering independent labels like Prestige?

.

JJM What are some hidden gems in the Prestige catalog?

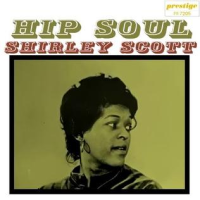

TR I think anything by Shirley Scott. The organ craze in jazz came and went, and when it was over, a lot of people just remembered that there were Jimmy Smith and a bunch of other guys. But those other guys – and most of them recorded for Prestige – were not Jimmy Smith imitators. They were creative talents in their own right. And Shirley Scott found things that an organ could do, and ways that it could expand the vocabulary of jazz, that were amazing. And what about Dorothy Ashby? She wasn’t just a novelty – the girl who played jazz on a harp. She was highly regarded as a session musician in a lot of different contexts. And the albums she made for Prestige with Frank Wess are amazing.

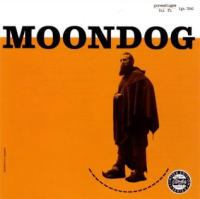

And I’ll give you one more who really surprised me. Not jazz, but I’ll give him to you anyway. I saw Moondog on the streets in the 1950s, with his Viking helmet, and I knew him as a colorful New York character. But I had no idea, until I started this Listening to Prestige project, that he was one of our great avant-garde composers. When he sued Alan Freed about the use of his name, both Benny Goodman and Arturo Toscanini testified as to his importance as a composer. And they were right.

.

.

_____

.

.

.

.

Listening to Prestige: Chronicling its Classic Jazz Recordings, 1949 – 1972. [SUNY Press]

.

.

About the author

Tad Richards is a prolific visual artist, poet, novelist, and nonfiction writer who has been active for over four decades. He is the author (with Melvin B. Shestack) of The New Country Music Encyclopedia and Jazz With a Beat [SUNY Press] among many books. He lives in Kingston, New York.

Click here to visit his blog, Listening to Prestige

.

.

“Written with a contagious enthusiasm and a breezy style that newcomers to jazz will find particularly rewarding, Listening to Prestige is a valentine to one of the foundational labels of post-war jazz. Tad Richards highlights scores of now-classic recordings by Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins, Thelonious Monk, Yusef Lateef, Jack McDuff, and countless others, while also opening a window on the modus operandi of Prestige’s founder Bob Weinstock and the stylistic changes coursing through jazz from the late ’40s through the early ’70s.”

-Mark Stryker, author of Jazz from Detroit

.

“When it comes to jazz, this is one of the rare books that we actually need, that does not cover the usual ground with the usual suspects. Prestige Records, for all the attention it has received from audiences, is not well known in the historical sense. Every jazz fan has these records, which is important, but few know the inside story, the complex process of the jazz independent label in the era before independent labels became as common as recording projects. And Tad Richards is the writer to do this, with a firm grasp of jazz’s historical succession, the bebop era, and the musical needs of musician and audience. Read this book.”

– Allen Lowe, saxophonist and historian who has recorded with Julius Hemphill, David Murray, Doc Cheatham, and Marc Ribot

.

_____

.

.

This interview took place on June 30, 2025, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita

.

.

.

_____

.

.

Click here to read the 2024 Jerry Jazz Musician interview with Tad Richards about his book Jazz With a Beat: Small Group Swing, 1940 – 1960

Click here to read the 2006 Jerry Jazz Musician interview with Ashley Kahn, author of The House that Trane Built: The Story of Impulse Records

.

Click here to read other interviews published on Jerry Jazz Musician

Click here to subscribe to the (free) Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter

Click here to help support the ongoing publication of Jerry Jazz Musician, and to keep it commercial-free (thank you!)

.

___

.

.

Jerry Jazz Musician…human produced (and AI-free) since 1999

.

.

.