.

.

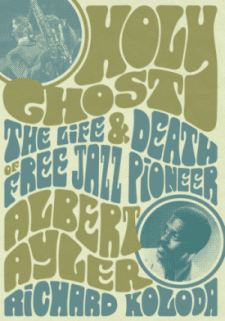

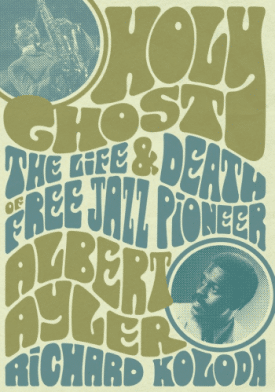

Richard Koloda, author of Holy Ghost: The Life & Death of Free Jazz Pioneer Albert Ayler [Jawbone Press]

.

.

___

,

,

…..The history of jazz is filled with artists whose music and personal character changed American music and enhanced its culture. Like it or not, Albert Ayler is one of them.

…..Derided by musicians, critics and fans from the time his recording career began in 1962, his raucous, jarring, challenging music elicited powerful emotions and biting criticism. To cite three examples, in their essential 2009 history, Jazz, Gary Giddins and Scott DeVeaux wrote that the poet Ted Joans likened Ayler’s tenor saxophone sound to “screaming the word ‘FUCK’ in Saint Patrick’s cathedral on a crowded Easter Sunday;” the critic, poet, and Black activist Amiri Baraka called Ayler’s “disarmingly naïve melodies”, “coonish churchified chuckle tunes;” and the eminent jazz critic Dan Morgenstern compared Ayler’s ensemble to “a Salvation Army band on LSD.” And these were his advocates.

…..From the outset, jazz was an avant-garde music, considered liberating and life-affirming by progressive listeners, but outrageous and scandalous to those who saw its emergence as a major contributor to society’s moral decay and decline, especially since its popularity came at the expense of white society’s discernment and refined cultural sensibilities. The result is that artists from that era were often subject to derision and ridicule (and hate), but few were as misused, misrepresented, or misunderstood as Ayler would be.

…..In Richard Koloda’s justifiably praised profile of Ayler, Holy Ghost: The Life & Death of Free Jazz Pioneer Albert Ayler [Jawbone], the author writes that “some critics considered [Ayler] a charlatan, others a heretic for dismantling the traditions of jazz. Some simply considered him insane. His divine message of peace and love, visions of flying saucers, and the strange account of his final days leading up to being found dead in New York City’s East River are central to his mystique, but they are also a distraction.”

…..Yes, a distraction from, for example, the inspiration Ayler provided John Coltrane, and how that influence changed the course of jazz; from his effect on avant-garde rock musicians like Patti Smith and Lou Reed; and from his belief that music held a profoundly spiritual power.

…..Koloda writes that “the mysterious manner of Ayler’s death tends to overshadow the blistering impact he had on the direction of jazz to come.” So, rather than being posthumously revered in a way Coltrane is, Koloda cites previous Ayler biographer Peter Niklas Wilson for writing that his spirit “seems to have evaporated into unreality. Albert Ayler was born to the myth, one to be dark and mysterious.”

…..PProvided with a wealth of material unavailable to previous Ayler scholars, Koloda’s book is an impeccably researched biography of an influential figure in American music, the goal of which is “to draw attention away from the circumstances surrounding Ayler’s death and bring it sharply back to the legacy he left behind.”

…..In my February 13, 2023 interview with Koloda, he talks about his work on Ayler, a “character” he describes “as interesting as any that could have been created by a Hollywood screenwriter.”

Joe Maita

Editor/Publisher

.

.

___

.

.

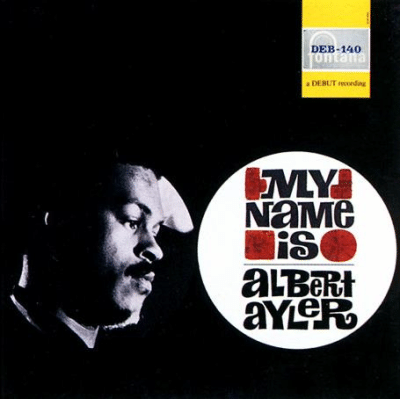

The cover of Albert Ayler’s 1963 album My Name is Albert Ayler [Debut Records]

The cover of Albert Ayler’s 1963 album My Name is Albert Ayler [Debut Records]

The jazz writer Val Wilmer described Ayler’s playing of “Summertime![]() ” from this album “a passionate expression of almost unbelievalble pathos. His dramatic swoops and masterly shading recall the sweeping glissandi of Johnny Hodges, while the completeness of his statement gives the lie to the notion that he was going through an ‘experimental’ period.”

” from this album “a passionate expression of almost unbelievalble pathos. His dramatic swoops and masterly shading recall the sweeping glissandi of Johnny Hodges, while the completeness of his statement gives the lie to the notion that he was going through an ‘experimental’ period.”

.

.

“My music is the thing that keeps me alive…But I must play music that’s beyond this world.”

-Albert Ayler

.

“He was coming from a place in the heart, a wordless place, one heart speaking to another. That’s what he was about…It broke his heart when the people didn’t respond. People often seemed stunned by the music. I think it was a question of timing. He came too soon after Ornette Coleman. People hadn’t had time to assimilate what Ornette had done. They weren’t ready for total freedom, for music that did completely without time and changes. Albert was a soldier on the battlefield in a war he couldn’t win.”

– The musician/composer Annette Peacock, who toured with Albert Ayler, and whose husband Gary played bass with Ayler in the mid-1960’s

.

.

Albert Ayler plays “Vibrations” from his 1964 ESP album Spiritual Unity, an album the jazz writers Gary Giddins and Scott Deveaux describe as having been “both cheered and ridiculed,” and that Ayler’s sound “evoked lusty hysteria.”

.

___

.

.

This interview was edited for clarity

.

JJM I really enjoyed your book, Richard. I have to admit that I own several Albert Ayler records, but I probably only listened to them once or twice after buying them in the late 1970’s. As most jazz fans know, he is a challenging musical artist to consume. When did you start writing this book?

RK Sometime around 1997, and I got involved in it by luck and by default. I am a book collector and like to patronize local library sales. While at one, I picked up Leonard Feather’s book, Encyclopedia of Jazz, and as I was thumbing through it, I noticed Donald Ayler’s address and phone number written in it, so I called him up and asked if he’d like to be a guest on my jazz radio show. Donald was amazed that someone would remember him after all those years. I figured his appearance would be a one-time thing, but it went pretty well, so I asked him to come back another time. Later, Albert’s father joined me behind the microphone.

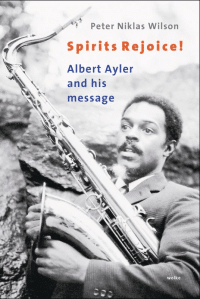

Peter Niklas Wilson’s biography of Ayler, Spirits Rejoice!

Donny suggested the idea of my writing a book on Albert, but I was going to law school at the time so it just wasn’t possible. I did feel though that if I were to ever write this biography, Donny and his father would be a great sources for it. At the time, Peter Niklas Wilson had already written a German- language biography about Ayler – which was at the time allegedly coming out in an English translation. It has recently has been published in an English translation by Jane White, many years after it was reported to be imminent.And Jeff Schwartz, an undergrad student, had put up a book-length bio of Ayler on the web in the early 90’s. However, I told myself that since I have a master’s degree in music, why not write the book?

Donald was a source for the book, but he give me the same interview over and over again. As I outline in Holy Ghost, both his health, and mental health, had deteriorated by that time. It was like pulling teeth to get him to talk, especially when he was drunk, when he would brag about being the greatest trumpeter in the world. But, all my research resulted in a 600 page manuscript, which my publisher [Jawbone Press] and I worked to tame into 300 plus pages.

JJM A goal of your book is to draw attention away from the circumstances surrounding his death and focus instead on his legacy. You wrote that doing so “demands confronting those [writers] who have marginalized, maligned, and spread misinformation about Ayler in order to further their own agendas.” Were you able to confront any of those writers?

RK Not really, because a lot of them have died.

JJM Is there a particular story that is an example of the misinformation being spread?

RK There were many stories about his death, one of which is of him being tied to a juke box and dumped into the bottom of the East River. When I was at Donny’s funeral Albert’s daughter brought that up, saying she heard stories about her father being tied to a jukebox. If you think logically about that, he’d still be down at the bottom of the river if he was, so this story is of course untrue, and it was a story that didn’t really kick in until seven years after he died. Also, The Cleveland Plain Dealer printed a “puff piece” in their Sunday supplement that alleged Ayler was killed over drug dealing—totally false based upon interviews with Ayler associates.

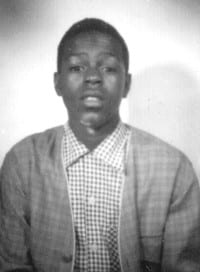

School ID photos of Albert (top) and Donald Ayler

.

(photos courtesy of the author)

JJM Music was very important to the Ayler family. What kind of music did he listen to as a child? Perhaps you found evidence of what his parents may have played for him on the record player?

RK His father Edward had a pretty decent collection of 78’s, and he and Albert’s mother Myrtle took Albert and Donny to see Count Basie in downtown Cleveland. Freddie Webster had a secondary influence on Don and it could be that his father owned Jimmie Lunceford records. Albert also liked Charlie Parker, and his girlfriend, Carrie Roundtree, had a good collection at the time, and she’d come over and listen to Sonny Stitt with Albert, and he’d play the “air saxophone” for her while listening.

JJM Albert was known as the “Charlie Parker of Cleveland.” Did he play a lot of bebop when he was young?

RK In the clubs people called him “Little Bird,” and Val Wilmer said that he actually met Parker. He was also familiar with R&B – he played for two summers with the blues musician Little Walter, toured with Lloyd Price and hung out and played with the Cleveland pianist Bobby Few while they were in high school. So, he played alto sax in emulation of Parker, and it wasn’t until he got out of the army when he switched to tenor sax, and he’d tell people his sound was the sound of the ghetto. But, while he enjoyed the experience, it wasn’t his style of music. He’d play standards too – a friend recalled hearing him play “Moonlight on the Wabash.”

JJM His time in the army is an interesting part of the story. After becoming the father of a son, Curtis, with his girlfriend Carrie Roundtree, he joined in order to avoid paying the eight dollars a week in child support. What kind of music education did he get in the army?

RK He spent time in Orleans, France, and was influenced by “La Marseillaise,” the French national anthem that reappears throughout his work, almost as a signature. The piece is a march in the New Orleans style, like a funeral march. He would also go on side ventures and play the jazz clubs in Paris, and he met up with Perry Robinson in Spain during one of his leaves.

One thing that is important to understand about the 1960’s is that African American musicians living in Europe were considered to be great musicians. For example, Albert’s friend Mutawaf Shaheed told me that even though he was a lousy bass player, when he was in Sweden they wanted to hear him play simply because he was African American. This carried over into my generation, the 1970’s, when I would hear from friends of mine about how merely being an American guitar player from the South would be good enough to get a gig in some of the clubs in Europe. So, it’s possible Albert was welcomed at clubs overseas simply for being Black.

JJM What inspired Albert to move into the direction of the avant-garde?

RK It started while he was in the army, which is interesting because it was the type of music they wouldn’t have tolerated – his commanding officer told everyone else to stay away from these “nuts” who played the avant-garde. But something overseas convinced him to go in this direction. It could have been meeting Perry Robinson in Spain, who was playing avant-garde music at the time, or it could be that he met other likewise people – Roscoe Mitchell, for example – who were all trying to find themselves musically.

Ayler’s 1965 ESP album Spirits Rejoice

…

“The true spirit [of the album Spirits Rejoice] was in New Orleans jazz, that’s what I’m trying to bring back into music, the true spiritual feeling or jubilation, a prayer to God…The artists who play this music are beyond the civilization that exists today.”

-Albert Ayler

JJM What was Albert trying to communicate with this music?

RK He was trying to express his soul and reach beyond reality. If you listen to his music, it is like a Black church service. He is speaking in tongues, basically, the entire time. Stanley Cowell referred to it as “Black country intelligence,” and Peter Niklas Wilson wrote that it was the soul from the Black churches. Albert’s maternal grandfather was a radio preacher in Alabama in the 1930’s and was very much into the Black church service, and his mother was a practicing Baptist. So, he was exposed to the church and when you listen to Albert’s solos it is as if he was talking in tongues, and many of his song titles are basically church services, where he’s the preacher.

JJM Did Albert attend any institutionalized church services later on in his life?

RK I’m pretty sure he didn’t because he was quoted as saying that he was once a Baptist, but that he had moved on from that. He did, however, write in the International Times that “you better find God before it’s too late,” but I have wondered if he actually wrote that since his father said something very similar to that during a radio show interview. So, his belief stayed with him until the end, and some people have speculated that Albert committed suicide by drowning because it was a way to atone for his sin through a re-baptism of the living to the dead.

JJM In one interview with Nat Hentoff of Downbeat, Ayler said: “We keep trying to purify our music, to purify ourselves, so that we can move ourselves – and those who hear us – to higher levels of peace and understanding.” What did he mean by “purify?”

RK I take it to mean that music is the healing force of the universe, and that to him, music was the way to communicate with God.

JJM Your book is filled with quotes about Albert from a variety of critics, and their take on his music is an essential part of the story…

RK Yes, it is an interesting part of the story, and, since I’m a lawyer, I treated the critics as if they were expert witnesses who presented their opinions of Albert in either the negative or the positive. So, as I would do in a court trial, I establish their credentials, present their opinions side-by-side, and then let the jury – in this case the reader – decide. I didn’t want to treat this part of the story as a “hero-worship” where only the positive reviews were presented, and I avoided doing any of my own analysis on Albert’s music. I was more intrigued by the contemporary opinions that critics had of Albert and his music, and to place them in their context; for example, were they written while he was alive, or were they post-mortem?

Something I did do was to look at the background of these critics. For example, Kenny Dorham was a bop trumpeter who hated Albert’s music and who probably saw his own music’s future drift away, but the well-known critic George Hoefer, who was a big fan of early jazz, raved about him. Others, like Amiri Baraka, pushed the Blackness of Albert’s music on to people, and even worse was the poet Ted Joans, who imposed his anti-white and antisemitic tropes on to people through his reviews of Albert and his white violinist Michel Samson, who he accused of being in “his parasitic-bag by intruding on Albert’s music.” So, there are plenty of examples of people imposing their agendas on readers while writing their reviews of Albert, which made some believe he was backed by Black radicals, poisoning Ayler’s reception. Similar was the Marxist historian Frank Kofsky, who railed against capitalist club owners as he pushed his neo-Trotskyite agenda.

JJM Did Albert have an opinion about any of these critics, or have a relationship with any of them?

RK He was friends with Ted Joans, and they were still talking as late as 1970, the year of Albert’s death. And Baraka wanted exposure through Albert…

JJM Baraka saw an opportunity to promote Ayler as a political voce of the avant-garde, but when Albert went off to Denmark, Baraka turned to Archie Shepp instead. Did Albert see free jazz as a political music?

RK No, he never did. His music was used to free his soul. If he thought of it as a political music he wouldn’t have had white musicians like Bill Folwell or Michel Samson or Gary Peacock in his band. He never saw his music as anything other than a way to envelop people into the web of his soul and his vision.

JJM I also get the sense he felt it was important to downplay politics in order to keep the listener’s attention focused on his music…

RK He was apolitical and I don’t think he really cared one way or the other about politics, and didn’t necessarily associate being Black or white. A part of this is because Albert went to John Adams High School, a heavily integrated school in Cleveland.

JJM As we know, listening to Albert’s music can be incredibly challenging. What is the key to understanding it and appreciating it?

RK I think it is to listen with open ears, and with your soul.

JJM What was your reaction to listening to his music for the first time?

RK By the time I first heard Albert I had already gotten into John Coltrane, so it wasn’t that much of a shock for me – it was just a little further out than Coltrane. I would put the records on while studying because I thought it would help me focus, so I was listening to it half-assed.

JJM The late German saxophonist and musicologist Ekkehard Jost wrote in the book Free Jazz that a key to understanding Albert’s music is to “smear his notes together into shapes and to think of the shapes as sound blocks…The notion of a shape is comparative to a sound block – a shape being a smear of sound. In these shapes the harmonic center disappears.” I found that somewhat effective in my understanding of his music, and to imagine listening to Albert’s music in these blocks…

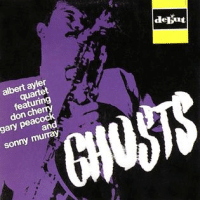

Ayler’s 1964 album Ghosts [Debut], an album jazz critic Scott Yanow suggests to readers in All Music Guide that “It helps greatly to have open ears to appreciate this music.”

…

“Albert did not say, ‘We are going to play this or that piece.’ Rather, he said things like, ‘Let’s play sadness. Let’s play hunger.”

– Archie Shepp

RK I would definitely agree with you. It is important to get away from focusing on notes and instead listen to his shapes and sounds. It’s similar to modern avant-garde music like John Cage’s “4’33″, where you can hear clicking and coughing in the audience amidst the silence, or the sound in the pavilion heard in Edgar Varese’s Poème électronique that replaces musical chords. You even hear it in rock music, where feedback from Jimi Hendrix’s guitar, for example, is part of the sound.

JJM You make the case that rock musicians have been influenced by Ayler…

RK Yes, Iggy Pop of the band The Stooges and Tom Verlaine from the band Television were taken by Ayler, and I think much of that is because, like Albert, they were outcast kids in their schools, and they found an inner release by focusing on their alienations. One way for doing that was to listen to “far out” recordings like Albert’s, and they in turn became musical outcasts themselves.

JJM It’s interesting that some, like Amiri Baraka, saw Ayler’s music as a connection to Black political and artistic movements, but in reality his music was most appreciated by the white hipsters of Greenwich Village…

RK Yes. The writer A.B. Spellman brought that up in his book Four Lives in the Bebop Business. At the time, Black people were more about integration rather than separatism, which was not a cool idea during the civil rights movement, and the music of Motown and Stax was palatable to both white and Black. But this music of course didn’t appeal to everyone, and the hipsters of the Village were open to crazy-sounding music, like Albert’s.

JJM So, while his music and the spirit of it wasn’t entirely overlooked by the Black community – whose real interest was in the soul music coming out of Detroit and Memphis and Philadelphia – Albert especially appealed to this outcast white persona niche you talked about who were also buying records by Coltrane and Ornette Coleman…

RK Yes. The last concert Albert did was in Massachusetts, where a soul group opened for him. It was a free concert but the house was only half-full, which was different after all the tickets he’d sell for venues in France, for example. This was pervasive until 1970, and he never played Harlem – he only played Greenwich Village.

JJM That brings up another interesting part of the story, which is that free jazz musicians – and not just Albert – were mostly shut out of New York’s jazz clubs because they weren’t bringing an audience, and also that the club owners were appalled by their sound. So, much of the development of free jazz took place in lofts and private homes…

RK Yes, that’s right. As an aside, Albert had a great appreciation for modern jazz – for example, he was seen by Bill Randall at a Dave Brubeck performance. He also had a high regard for the avant-garde classical composer Charles Ives, mentioning him in a 1970 French interview.

JJM So, he was aware of and had an appreciation for a variety of traditional and modern music. What did some of the jazz musicians of his era – and the era prior – think of Albert’s music?

RK Some of them really liked it. The saxophonist Don Byas was one, even saying that the way Ayler played was the way he himself had always wanted to play. Louis Armstrong was appreciative of Albert; Donny told me that he hung out with Ayler’s band at Newport. But there were of course many musicians who didn’t like what Albert was doing – many wouldn’t listen to it—such as Kenny Dorham, or Miles Davis.

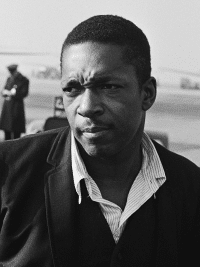

Gelderen, Hugo van / Anefo, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

“I think what he’s doing, it seems to be moving music into even higher frequencies…he filled an area that it seems I hadn’t gotten to.”

-John Coltrane

JJM John Coltrane was heavily inspired by Albert. What did he see in Albert’s music?

RK Probably an extension of himself. Coltrane said that Albert was further out than he was, and that Albert took music to places Coltrane hadn’t yet imagined. Albert saw himself as a “holy ghost” among the free jazz musicians – Coltrane being the “father,” and Pharaoh Sanders being the “son.”

JJM Another free jazz giant was the pianist Cecil Taylor. Was he wary of Albert’s emergence, or feel any sort of rivalry with Albert?

RK I don’t think so. There was a piece on Cecil published in the Cleveland Plain Dealer in 1997 in which he praised Albert, and there are also photos of the two of them in France in 1966 that displays their friendship. So, I don’t think Taylor ever viewed him as a rival, he just probably realized he had to take a separate path than Albert. It wasn’t as if he was scared or wary of Albert; as far as I’m concerned, a rivalry didn’t exist.

JJM The record executives Bernard Stollman and Bob Thiele played important roles in Albert’s career. Stollman signed him to a recording contract on his fledgling label ESP Records. What did he see in Ayler’s music? Did he see a financial opportunity, or did he have more of an interest in promoting Albert’s musical vision?

RK Stollman didn’t really understand Albert’s music, and he obviously knew there was no financial market for this music. He did feel that “something” was there and that his mission was to document it. His philosophy was that the artists decide what you hear on ESP, not the management, and that he was doing his part in documenting this part of the American vision. On the other hand, Donny would tell me stories about how Impulse Records, where Thiele worked as head of the label, didn’t pay them royalties, using Don’s song “Our Prayer” as an example. That song was hailed by critics like Gary Giddins as being one of the best jazz songs of 1966 and eventually recorded by people like Carlos Santana, and Donny told me he could have used the royalties from that song…

JJM So, Stollman saw a duty in cataloguing Albert’s music, whereas Impulse and Thiele – after signing Albert to the label in 1966 – saw a financial opportunity with Albert. Did Thiele see Albert as having the potential for being a big star?

RK Yes, he did, but while people blame Thiele for Albert’s change in style – for example, incorporating the vocals of his girlfriend Mary Maria Parks singing into his music – that’s up for debate. Mary Maria said that Albert heard her poems and decided to set them to music, but everyone blames Thiele for that.

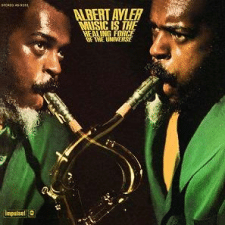

They call the Impulse recordings the “abysmal” albums, but Thiele was gone from Impulse by the time they were recorded. And not all the Impulse albums are bad – I like Music Is the Healing Force of the Universe, and for whatever reason the younger generation appreciates those recordings.

JJM A centerpiece of Albert Ayler’s biography is his relationship with brother Donald. He hired him even though he wasn’t a particularly capable trumpet player, only to years later fire him from the band. Talk a little about their relationship, how they interacted musically and the circumstances leading to the firing?

RK Donny was a great sax player in high school, and some sources indicate that he could outplay Albert at that time. He showed up at an Elvin Jones concert in New York once and floored everyone by the way he played saxophone. However, Albert couldn’t see the need for another sax player in his band, so Donny needed to transpose his vision for that instrument into the trumpet. His style may have made Albert’s playing more simplistic, but I suspect Albert was trying to get that way anyway.

Albert needed Donny to fit in, but Donny’s problem was his drug abuse, which he blamed on Mary Maria Parks instead of himself. He had a very fragile personality. In the last chapter I write about him making somewhat of a comeback, and I’m happy that my book puts a positive message on his place in jazz music history. He received rave reviews while playing in Italy during the early 1980’s, and when he would play in Cleveland people there still liked him. It’s just that his gigs started drying up because of his drug abuse, and mental-health problems.

JJM So, this was after Albert’s death…What was the reason for Albert firing Don?

RK Donald blamed Mary Maria Parks – who was acting as Albert’s business manager at the time – and Bob Thiele, but I suspect it was Mary Maria because she claimed that Thiele called Albert and told him to fire Donny. The problem with that story is that Thiele wouldn’t have had any control over who Albert kept in his working band – he only had control over the recording sessions.

Toward the end of Albert’s life, Donny claims that Albert asked him to be in the band for his French concerts, and I found evidence that supports that in the original ads in the French jazz magazines –that list a sextet. But Donny refused because he didn’t like the way Mary was involved in the band, “singing that rock’n’roll.” He didn’t feel he fit into that and declined Albert’s request to rejoin the band. So, there was an intermittent period where Donnie got clean, and he did it while being home in Cleveland.

JJM Albert fell into a deep depression prior to his death. What eventually broke his spirt?

RK I think it was his mother pressuring him to take Donny back into the band. She didn’t blame Donny for his drug problems; instead, she blamed Albert, and even told the film producer Jacqueline Caux that she wished he’d never been born. So, he felt a lot of family pressure around his relationship with Donnie, and looking at this from today’s perspective, if he had received help for his mental health issues he might still be with us. But mental illness in the 1970’s was the subject for late night comedians; it wasn’t accepted at the time in the same way a physical illness was.

JJM Albert was someone who took his work very seriously, but he was the subject of much ridicule and rejection. You describe in the book how on many occasions the only people in the audience were members of his family and friends. Did this rejection compound his depression?

RK I think so, and it could also be that he felt that his message got out there, and that was enough. There is a story that Mary Maria Parks tells about Albert smashing his saxophone into a television, but he may have done that out of frustration over her and wanted to be rid of her. It is also possible he had another girlfriend. Family members say that he didn’t want to take Mary on his tour to Japan and he told his maternal cousin of an altercation he had with her, and then he just got out of there.

The thing is, though, that while he wanted to leave, he had no place to go, which is probably why he had his passport in his pocket. He needed his passport for his upcoming trip to Japan. Donny also said that he pawned his saxophone, and the pawn ticket was found on him as well. So, his suicide may have been a spur-of-the-moment decision. He may have been wandering around New York, homeless, or it is possible that he got turned away by his new girlfriend.

Music is the Healing Force of the Universe (Impulse!; 1969) , the last studio album recorded before Ayler’s death in November 1970

…

“It’s late now for the world. And if I can help raise people to new plateaus of peace and understanding, I’ll feel my life has been worth living as a spiritual artist.”

-Albert Ayler

I wanted to get the police report of their finding his body, just to verify that his passport and pawn ticket were in his pockets. I requested the report via a Freedom of Information Act filing, but never received a response, so I then wrote to Mayor Bloomberg and Governor Cuomo concerning this, but as it turns out the files had been thrown out. I had hoped to at least find out if Mary Maria Parks had ever filed a missing person’s report on Albert with the police. It is unbelievable to me that she would have had a relationship with Albert and not even call the cops to report that her boyfriend, who was very depressed, walked out and couldn’t be found. So, I don’t know if she kept quiet about Albert’s leaving, or if she had filed a missing person’s report. I also wanted to get a copy of his autopsy report just to be able to write a verbal description of it, but non-family members were blocked from getting it. There are still so many questions about what can be found out there about Albert, so maybe another writer will come along someday to cover bases I wasn’t able to get to.

JJM There are several theories about his death – many unfounded and ridiculous, like the juke box story. Some have felt that he was late in paying off drug debts, or that somehow the Mafia may have gotten to him. After writing your book, what do you think happened?

RK I simply think that after wandering around New York for a couple days, he made this spur-of-the-moment decision to kill himself. He probably didn’t have the money to buy a gun, so he just jumped into the river. How else would he do it? Cut himself? Overdose on drugs he didn’t have access to? So, he was deeply depressed and simply jumped into the water.

JJM What have you learned about the essence of Albert Ayler after having this experience of writing about him?

RK That he was a great philosopher, and that me made people’s souls richer from listening to his music.

.

Photographer uncredited, but likely Chuck Stewart/via Wikimedia Commons

“Ayler’s creations, even at the end, were far larger than life; his conflict and pain and poverty were those of a hero albeit Albert was a hero unfortunately like you and me in outward appearance. His was a classic art. His strange death prematurely deprived American music of all kinds of one of its outstanding vital forces. If we are to become a civilization, Ayler’s kind of humanist understanding, his depth and complexity, even his kind of contrasting simplicities and innocences, must become part of our character. We cannot all be heroes, but it may be that we can someday be the more sensitive individuals that Albert Ayler thought we might be.”

-John Litweiler, jazz critic, former editor of Downbeat, and Ornette Coleman biographer

.

.

“Prophet” is from Ayler’s 1965 ESP album Spirits Rejoice, and includes Ayler (tenor saxophone); Donald Ayler (trumpet); Charles Tyler (alto saxophone); Gary Peacock (bass); Henry Grimes (bass); and Sunny Murray (drums). The critic Steve Huey writes in All Music Guide that the song “touches on a different side of Ayler’s old-time march influence, with machine-gun cracks and militaristic cadences from Murray driving the raggedly energetic ensemble themes.”

.

.

___

.

.

Holy Ghost: The Life & Death of Free Jazz Pioneer Albert Ayler [Jawbone Press]

by

Richard Koloda

.

.

Click here to read an excerpt from the book

.

.

About Richard Koloda

Richard Koloda has a master’s degree in Musicology from Cleveland State University, having written a thesis on the piano music of Frederic Rzewski. He was a contributor to the critically acclaimed documentary My Name is Albert Ayler by Swedish filmmaker Kasper Collin and a consultant on Revenant Records’ ten-CD retrospective of Ayler, Holy Gost: Rare and Unissued Recordings (1962 – 70), which has been called “the Sistine Chapel of box sets.” Richard lives in Wayland, Ohio, where he practices law. When he is not in court, he is working on his second book (not about music).

.

.

Praise for Holy Ghost

“The facts of Ayler’s life have for years been hard to come by, and stories told about him are mythological, some even ghostly. Koloda’s book remarkably reconstructs Ayler’s life story and explores the controversy he created.”

– John Szwed, author of So What: The Life Of Miles Davis

.

“Anyone who has gone to the crossroads with Robert Johnson or thrilled to the Wicked Pickett’s cross-grained scream can recognise and identify the vernacular voices inhabiting Ayler’s vision. Richard Koloda draws on archive material and fresh oral history to document aspects of an American family and the passage of an uncompromising artist who took no prisoners.”

– Val Wilmer, author of As Serious As Your Life: Black Music And The Free Jazz Revolution, 1957–1977

.

“Reading like an action-packed novel, Koloda’s biography is definitive, colorful, and a major addition to the literature of American music and jazz.”

– Scott Yanow, author of Jazz On Record 1917–1976

.

“Koloda’s deeply perceptive, revelatory, and vibrant biography confirms beyond a doubt Albert Ayler’s standing as a visionary in the jazz pantheon.”

– Booklist (starred review)

,

“A scrupulous and propulsive biography with a stated agenda: to clear up some of the myths and misperceptions surrounding one of jazz’s most mysterious major figures.”

– Nate Chinen, WRTI

.

“Adds a great deal to Ayler scholarship, and to the history of avant-garde jazz in general.”

– The Wire

.

“An important book that comes at a time when many listeners and critics are rediscovering Ayler’s work. It combines analysis of the recordings and descriptions of Ayler’s short life very effectively, and makes one keen to return to listen to his music.”

– London Jazz News

.

.

This interview took place on February 13, 2023, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita

.

.

.

___

.

.

Click here to be taken to the Jerry Jazz Musician interview archive

Click here to subscribe to the Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter (it’s free)

If you enjoyed this interview and would like to read more like them in the future (and to help this site remain commercial-free), please click here to help support the continuing publication of Jerry Jazz Musician (thank you!)

.

.

.

Only One I can think of = COOL = Artist Peter Herley