.

.

Great Encounters

Book excerpts that chronicle famous encounters among twentieth-century cultural icons

,

,

____

.

.

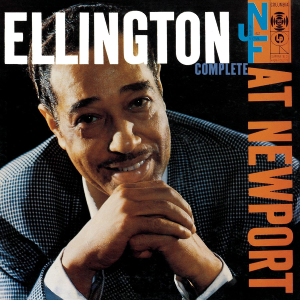

Duke Ellington at Newport, 1956

As told by Newport Jazz Festival founder George Wein

.

.

Excerpted from

Myself Among Others: A Life in Music

by

George Wein

.

.

__________

.

.

Nineteen fifty-six was the Newport debut of the Duke Ellington Orchestra. I had struck an agreement with Irving Townsend, Columbia Records’s A&R man, earlier in the year. It would be good publicity to have some recordings from Newport. Our arrangement seemed like a good deal: for each artist recorded, the record company was to pay us an amount equal to that artist’s performance fee. As it turned out, it was a terrible deal, because the record company got exclusive rights and all of the royalties.

Columbia recorded the equivalent of four LPs during the 1956 festival: Louis Armstrong & Eddie Condon at Newport (CL 931); Dave Brubeck & J. J. Johnson-Kai Winding at Newport (CL 932); Duke Ellington & The Buck Clayton All-Stars at Newport, two vols. (CL 933); and Ellington at Newport (CL 934).

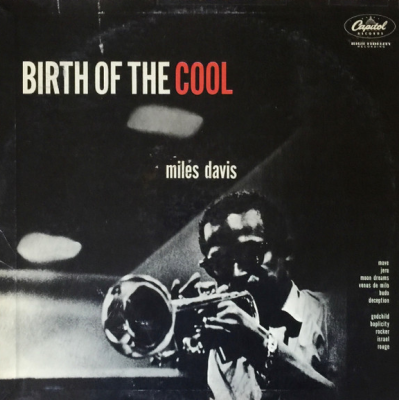

History, aided by this last LP, has rendered Newport ’56 practically synonymous with Ellington. Like Miles Davis before him, Duke came to the festival in the midst of a discouraging critical and commercial slump. The band had not been faring well in recent years. Duke didn’t even have a record deal at the time; he and Irving Townsend casually discussed the terms of a contract in a tent backstage. It was this festival appearance that launched the next highly successful phase of Ellington’s career. Duke’s victory, however, was uncalculated. He had not, as some reports have it, deliberately chosen Newport as the platform for his comeback.

On the opening night of the festival, Thursday, after we had changed out of our sopping clothes, everyone joined the Lorillards for a kickoff party at Quartrel. Louis and Elaine once again served the traditional Newport dinner party fare: scrambled eggs and champagne. At about two o’clock in the morning, there was a phone call for me. It was Duke. He asked me how things were going at the festival.

“Everything’s fine,” I replied. “What are you planning for your show on Saturday?”

“Oh, nothing special,” he said casually. “A medley, and a couple of other things.”

“Edward,” I admonished gravely, “here I am, working my fingers to the bone to perpetuate the genius that is Ellington-and I’m not getting any cooperation from you whatsoever. You’d better come in here swinging.”

Duke was comfortable enough with me to endure this sort of reprimand. I suspect that he considered Newport as just another gig, and he was prepared to treat it that way. But I was keenly aware of the need for new material and a strong showing by the band. Duke assumed that people wanted to hear “Mood Indigo” and “Sophisticated Lady” — hence their place in the medley. And, while a large portion of any audience probably would be happy with such a performance, an important minority wanted to hear new material. This minority included Duke’s most loyal fans. It also included all of the critics who were poised to tear up any artist who appeared to be performing by rote. It would be disastrous if Duke and his men took the Newport stage and sleepwalked their way through the old familiar book.

I had commissioned or requested new works from a number of groups that year. The Charles Mingus Sextet had debuted two songs — “Tonight at Noon” and “Tourist in Manhattan” — on Thursday night. J.J. Johnson had composed a piece that would premiere on Friday night as “PT.” Teddy Charles was to play four new compositions on Saturday afternoon. Duke had promised something as well. He and Billy Strayhorn delivered with a three-part suite so hastily assembled that, as Duke announced: “We haven’t even had time to type it yet.”

The final concert of the 1956 festival began and ended with Ellington. The band took the stage promptly at 8:30, christening the affair with “The Star-Spangled Banner” before moving on to old favorites “Black and Tan Fantasy” and “Tea for Two.” The set was then cut short; the band would not again take the stage until the last set. I had planned the evening in this fashion; I would never have opened a show with Ellington, unless it was a brief introduction. The first few songs were to be a taste of things to come, and the band was to come back to close the evening. This was the way I had programmed the show a few nights earlier, with Count Basie. And so the Ellington band whetted the crowd’s appetite, then surrendered the stage to the Bud Shank Quartet, the Jo Jones Trio, Jimmy Giuffre, Anita O’Day, the Friedrich Gulda Septet, and the Chico Hamilton band.

For more than forty years, the only public document of the Ellington set was Columbia Records’s Ellington at Newport (CL 934) — Duke’s all-time best-selling album. And for all that time, overdubbed crowd noise and spliced-in Newport ambience masked the fact that over half of the album was recorded in the studio on July 9, the Monday after the festival. This included the entirety of “The Newport Suite.”

Fortunately, the LP did include the now legendary live performance of Ellington at Newport in 1956: a medley of “Diminuendo in Blue” and “Crescendo in Blue,” charts #107 and #108 in the Ellington book. More specifically, the climax was a twenty-seven chorus tenor solo interlude by Paul Gonsalves, linking the two tunes. This was the performance that put the Ellington band back on the map.

Most accounts have it that “Diminuendo” was a surprise call by Duke. One story has Duke assembling the band backstage and suggesting the number, and the band looking around at each other in bewilderment. Then Paul Gonsalves asks, “That’s the one where I blow?” Duke answers, “Yes, and don’t stop until I tell you.” If this scene is to be believed, we might also consider Gonsalves’s recollection, as reported by Phil Schaap, that he first played the “Diminuendo” interlude to an empty house at Birdland in 1951. Paul claimed that Duke promised to feature him on the tune again sometime, in front of a much larger crowd.

Whatever the case, the consensus has it that “Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue” was a surprise to the band as well as the fans. It was to be the show-closer. Duke likely placed it in that spot in lieu of the Newport Suite, which had been recorded the day before in New York, but was still rough around the edges. I like to think that the decision could have been a direct response to my earlier admonition.

Duke kicked off the tune with three confident piano choruses. I was standing on the side of the stage during the performance, along with many of the musicians who wanted a better view. Jo Jones was sitting back there, egging Sam Woodyard on. The band barreled through the arrangement and the first movement reached its climax. Then Gonsalves took center stage.

Paul Gonsalves had been with Duke’s band since autumn of 1950. He had stepped into the formidable shadow of his hero — Ellington’s last great tenor, Ben Webster. Paul was in fact a devotee of Webster. But he had paid his own dues as well, working with Basie and Gillespie in the 1940s. He was a moving ballad player. In fact, it was for this talent that Paul was known — before his Newport appearance associated him with hard-blowing blues.

His ballad playing reflected a bit of his personality: He was a diffident person, quite the introvert. He was also something of a lost soul. It was possibly only within the structured, organic setting of Ellington’s band that Paul could achieve greatness.

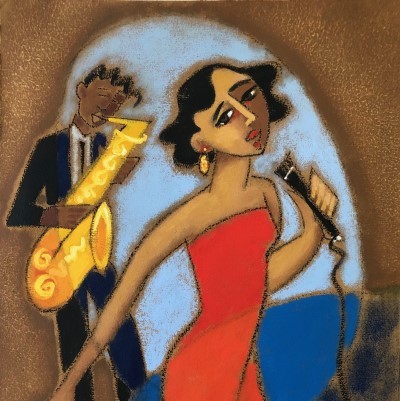

At the proper moment, Gonsalves dug in with his tenor and started blowing. Somewhere around the seventh chorus, it happened. A young blonde woman in a stylish black dress sprung up out of her box seat and began to dance. She had caught the spirit, and everyone took notice — Duke included. In a few moments, that exuberant feeling had spread throughout the crowd. People surged forward, leaving their seats and jitterbugging wildly in the aisles. Hundreds of them got up and stood on their chairs; others pressed forward toward the stage. Sam Woodyard and Jimmy Woode kept driving the beat mercilessly. The power of that beat, and the ferocity of Paul’s solo, is what stirred the crowd to those heights. Duke himself was totally caught up in the moment. The audience was swelling up like a dangerous high tide.

By the time Cat Anderson hit the final blast of “Crescendo,” the sea of bobbing heads had whipped itself into a squall. The tune ended and the applause and cheering was immense — stronger, louder, and more massive than anything ever heard at a jazz concert before. I was concerned with the crowd, as was the festival security. Although several thousand fans had left the grounds earlier in the evening, there were still 7,000 people screaming for more music. Well aware of the situation, Duke wisely followed the powerhouse blues with something more precious and low-key.

“I’m sure if you’ve heard of the saxophone,” he declared, “you’ve heard of Johnny Hodges.” Hodges, who had rejoined the band in the fall of ’55, was still one of Duke’s most beloved sidemen. Hodges played “I Got It Bad and That Ain’t Good,” and the crowd relaxed. Then the band did “Jeep’s Blues,” once again with Hodges.

Seeing an opportunity to cut things short, I waved to Duke to stop the show and to get off the stage. But to my chagrin, he grabbed the microphone and reassured the crowd: “Oh, we’ve got a lot more, we’ve got a lot more, we’ve got a lot more.” They ate it up. He called “Tulip or Turnip,” a vocal feature for Ray Nance. Once Nance got on, there was no going back.

The years had wiped out my memory of the following sequence of events. The reissued concert tapes bring it all back. As “Tulip or Turnip” drew to a close, I ran out and seized the microphone.

“Duke Ellington, Ladies and Gentlemen! Duke Ellington!” The crowd was in a state of uproar. The band was exultant, willing to play all night. Listening to the recording, you can hear me telling Duke: “That’s it!” End of story! You can also hear Duke pleading with me: “One more. We can do one more.”

“Nope!”

“One more, George. They want one more.”

“No, Duke!”

The crowd was demanding more Ellington. Angry boos mixed with cheering. I was without question the most unpopular person around at that moment. They wanted another song.

“No! No! I mean it now, Duke.”

His eyes were looking blankly in my direction, as if through me. I could tell he was trying to think of the next tune.

“Let me tell them good night,” he pleaded. “Can I tell them good night. . . ”

“No more music, Duke. . . ”

But I let him approach the microphone for a final adieu, one last “We love you madly” for the masses. They quieted as Duke stepped up and began to speak.

“Thank you very much, Ladies and Gentlemen.” The roar began again. Duke continued over the din. “We have a very heavy request — for Sam Woodyard! And “Skin Deep”!

Heedless of my fruitless commands, Duke had gone right ahead — calling a drum feature! I shouted again, in vain. It was out of control, out of my hands. Woodyard drilled a barrage of syncopated eighth-notes and rolls. The horns came in again, swinging. It’s much easier for me to enjoy this now than it was then. My heart was beating in my chest, keeping time with Woodyard’s double bass drums. When would it end? Well, after “Skin Deep,” the band slipped into something more comfortable: “Mood Indigo.” And, over the dulcet sweep of his saxophone section, Duke spoke the final words of Newport ’56: “Ladies and Gentlemen, we certainly want to thank you for the way you’ve inspired us this evening.

You’re very beautiful, very sweet, and we do love you madly. As we say good night, we want to give you our best wishes, and hope we have this pleasure again next year. Thank you very much.”

What prompted Duke to play as much as he did that evening? It was not merely the allure of playing to his most responsive audience — although there’s no doubt that this was a major factor. Duke’s marathon performance was a masterful exhibition, not only of musicianship but also of his awareness of the power of music. Had the band left the stage after “Diminuendo and Crescendo,” or even after “Jeep’s Blues,” it would have been wrong. The track after “Tulip or Turnip,” which contains my argument with Duke, has been listed in the reissued CD as “Riot Prevention.” This is a rather colorful exaggeration; jazz fans do not riot. Nevertheless, this was a crowd to be reckoned with, appeased. And so Duke Ellington gave them what they wanted. He gave them more than they could ever hope to absorb. “Skin Deep” was the final of several climaxes that evening, and he knew that eventually things would cool down. Duke taught me a lesson that night, one of many I would learn by his example. This particular lesson would come in handy on several occasions in the unforeseeable future.

It was an historic occasion; it was perhaps one of the first musical “happenings” of its kind. That sort of audience response would become more common in the soon-to-come rock-and-roll era; they have happenings like that all the time. But no one had ever witnessed anything like it in 1956, and no one could have predicted or expected it. It was purely a result of the power of that timeless, swinging music. In retrospect, the length of Gonsalves’s tenor solo and its commercial appeal might have had a future influence on the willingness of producers to record lengthy solos by such giants as Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane.

I can’t remember what I said to Ellington after the performance. I do recall that he was in a state of euphoria. He had just had the greatest performance of his life, and he probably suspected as well as anyone the impact it would have on his career. Columbia Records made a major record out of Ellington at Newport. And although the album was in large part a studio fabrication, the piece “Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue” was the genuine article. It would have been futile to attempt to recapture that once-in-a-lifetime performance.

The success of the album was due to a simple fact: Duke at Newport was much more than the music. It stood for everything that jazz had been and could be. It was the story of Duke Ellington and the story of Paul Gonsalves. It was the story of the blues, majestic and low-down and utterly real. Duke’s image soon graced the cover of Time magazine. Like Miles Davis the year before, Ellington had not only ended a long dry spell; he had used the stage at Newport to skyrocket to new heights. The slump was over.

.

.

Listen to “Dimuendo in Blue”

.

.

_______

.

.

Myself Among Others: A Life in Music

by

George Wein

.

_____

.

Excerpt from Myself Among Others: A Life in Music, by George Wein. Copyright © 2003 by George Wein. Used by permission of Da Capo Press.

CAUTION: Users are warned that this work is protected under copyright laws and downloading is strictly prohibited. The right to reproduce or transfer the work via any medium must be secured with Da Capo Press.

.

.

___

.

.

Click here to read a 2003 Jerry Jazz Musician interview with George Wein

Click here to subscribe to the (free) Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter

Click here to help support the ongoing publication of Jerry Jazz Musician, and to keep it commercial-free (thank you!)

.

___

.

.

Jerry Jazz Musician…human produced since 1999

.

.

.