Great Encounters

Book excerpts that chronicle famous encounters among twentieth-century cultural icons

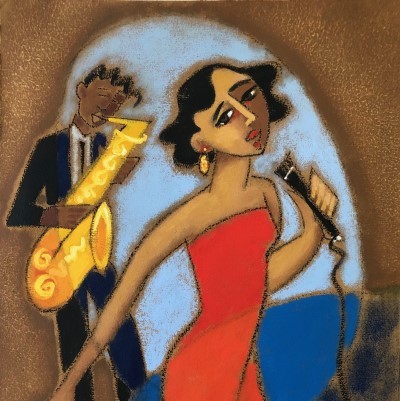

When Lionel Hampton Hired Dinah Washington, 1942

_____

Excerpted from

Queen : The Life and Music of Dinah Washington

by

Nadine Cohodas

*

Listen to Dinah Washington sing The Man I Love, with Lionel Hampton’s orchestra

___________________

Editors Note: The “Ruth” in the excerpt is Dinah Washington

As Ruth was settling into the Garrick, Lionel Hampton and his sixteen-piece band were getting ready for a weeklong stay at the Regal that would include a gala Christmas and New Year’s performance with Billie Holiday. It was a heady time for a group that was barely two years old and was riding a wave of ecstatic reviews and sold-out houses. The band had recently made its first recording for Decca.

“Hamp,” as he was universally known, was a consummate showman, a fireplug of energy who inspired his bandmates and thrilled his audiences. “Let it jump, but keep it mellow,” he liked to say. Hampton had started out as a drummer for Louis Armstrong. In 1930, when he was just twenty-two, Armstrong asked him to experiment on the vibraharp, a relatively new instrument that resembled a xylophone but was electrified to give it more kick. Hampton never looked back, though he enjoyed taking a turn on the drums or piano as the spirit moved him.

In 1936 Hampton followed pianist Teddy Wilson into Benny Goodman’s group, making a trio a quartet. It was the first integrated jazz combo — at once a wonderful and sobering experience, the chance to make great music with great exposure but with the constant reminder of racial prejudice. “I don’t know how many times Teddy and I were mistaken for servants — Mr. Goodman’s valet or the water boy for the Benny Goodman orchestra,” Hampton recalled in his autobiography, Hamp. He praised Goodman for trying to protect his musicians as best he could, insisting that they be treated like their white colleagues. On a cross-country trip from Los Angeles to Atlantic City — Hampton’s first ever plane ride — he composed “Flying Home,” the up-tempo instrumental that became his signature song and an audience favorite.

By the late summer of 1940 Hampton was ready to form his own band, encouraged by his wife, Gladys, who was as much partner as mate. She found the musicians, negotiated for instruments, picked the uniforms, got the train tickets, secured hotel rooms, handled the money, and took care of Hampton off the bandstand. It was a partnership that endured even in the early days when, Hampton (something of a philanderer) confessed, “I was a bad boy.”

The band had introduced itself to Chicago in February 1941 when they came for what was supposed to be a six-week stay at the Grand Terrace. On opening night more than a thousand customers were turned away, and the six weeks turned into a four-month engagement. In the fall, Hampton and band returned to Chicago, this time to play the Panther Room. Different venue, different audience — same response. They were a hit. “From seven-thirty until nine, Hamp played music soft but with a jump. From nine on they tore it up,” said Down Beat, which dubbed Hampton “the jumping jack vibe king.”

Hampton was using singers sporadically, though he had asked Billie Holiday to sing with him full-time. She declined because she wanted to be on her own but agreed to do occasional guest appearances. By the end of 1941 Hampton had hired a Chicago man, Rubel Blakey, a singer well-known on the city’s club circuit. Periodically Hampton brought in women singers, too, and when he got to the Regal for the December 1942 run, Lois Anita was on the bill with Blakey even though Holiday was set to do another guest spot. Joe Glaser, who owned Associated Booking Corporation and handled Hampton’s schedule, had been after the bandleader to hire a regular “girl singer,” as Hampton put it. Finally Hampton was giving the idea serious consideration.

In December 1942 he and Ruth were in the same city but they were playing in different worlds. Hampton was on a grand theater stage, Ruth in the second-tier showroom of a small club, albeit on Randolph Street. One was a household name, the other an unknown, not even billed when she sang, not sure what would follow when the Garrick job was over. But if timing is everything, Ruth’s was impeccable. She was ready to be noticed when Hampton was looking.

Many people take credit for the match: Joe Glaser, the comedian Slappy White, and Hampton band member Snooky Young all claim to have suggested that Hampton go to the Garrick to hear Ruth sing. Hampton remembered — erroneously — that Ruth was the washroom attendant who came out into the club every chance she could to sing with whatever band was playing. In a 1952 interview Ruth herself recalled that Joe Sherman brought Joe Glaser to hear her, and that the next night Glaser returned with Hampton.

Whatever the impetus, one night in late December, after his show at the Regal, Hampton went the fifty blocks north to the Garrick. On the small stage, Ruth was finishing her set with the Cats and the Fiddle. She had made good use of her time at the Stagebar, going downstairs every chance she could to watch Holiday in the Downbeat Room. With her gospel background, Ruth already had her own sound, but there was much to be learned about phrasing and emphasis and the intangibles that make a performance memorable. At some point Hampton asked her to sing “Sweet Georgia Brown.”

It would have been understandable to be nervous. The stakes couldn’t be any higher. But Ruth didn’t lack confidence. Although she had just turned eighteen, she had been singing in front of other people since she was ten and began giving solo recitals at fifteen. Now was the time to draw on that experience. This was her moment. By the time she got to “It’s been said she knocks ’em dead when she lands in town,” Ruth had done just that. Hampton was sold.

Even in such an informal audition he appreciated her talent. “I knew she was the girl I was looking for,” Hampton said. He liked her “gutty style.” It wasn’t that she was brassy. Her voice was too crisp and clear for that. But she sang with conviction, direct yet with feeling. Hampton was certain she could be heard “even with my blazing band in the background.”

Hampton invited Ruth to be part of the year-end show at the Regal, which was an hours-long gala each night packaging Hampton’s music with two comedy acts, the Two Zephyrs and Butterbeans and Suzy, one of the most popular duos on the circuit. Billie Holiday was a guest star. Patrons who wanted to see the weekly movie were treated to Eyes in the Night starring Edward Arnold, Ann Harding, and Donna Reed along with a newsreel of All-American Negro News.

There was one more matter. If she was going to sing with a big band, and a hot one at that, the plain and pedestrian “Ruth Jones” would not do. Hampton and Glaser claim credit for giving Ruth a new name. But verifiable chronology suggests it was Joe Sherman who came up with “Dinah Washington.” “You ought to have something that rolls off people’s tongues, like rich liquor,” he explained, and to him “Dinah Washington” fit the bill.

Why “Dinah”? Perhaps it came to mind in tribute to Ethel Waters, a heroine in the black community: a successful singer, success in movies and on Broadway. A decade earlier she had had a hit with the single “Dinah.” More recently, Dinah Shore, the popular white singer, had just signed a movie deal and was in the news. So “Dinah” would strike a chord with blacks and whites.

Why “Washington”? Like Lincoln and Roosevelt, it was the name of a president, thus a name of distinction and not unusual to find in either the white or black community. Together the two words had rhythm, indeed the same rhythm as the names of two current stars, Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald: two-syllable first name, three-syllable last. “Dinah Washington” it would be. Trumpeter Red Allen, who was playing at the Downbeat Room, remembered introducing the young singer, “burlesque style as ‘Dynamite Washington.'”

Two years earlier Ruth had left the Regal stage as an amateur, walking off with the few silver dollars the winner took home. Now she was back as Dinah Washington, a professional determined to make the most of it. “She walked out on that stage like she owned it,” Hampton recalled.

A writer for Down Beat happened to take in the show. The next issue included a short article on page four about the performance. “Dinah Washington Has South Side Debut,” said the headline. The story said the audience “was greeted with a surprise introduction when Dinah Washington previewed at the Regal for her first South Side appearance.” “Dianah [sic], currently at the Stagebar in the Loop, showed remarkable ability on all fronts.” Though only one paragraph, the story gave the moment official status, committing to the permanent record the creation of Dinah Washington from the raw material of eighteen-year-old Ruth Jones.

After the show Hampton asked Dinah to go on the road with him. She didn’t hesitate a moment to say yes. And there was more good news: she would get a raise, to $75 a week.

______________________

Queen : The Life and Music of Dinah Washington

by

Nadine Cohodas

_____

Excerpt from Queen : The Life and Music of Dinah Washington, by Nadine Cohodas. Copyright © 2004 by Nadine Cohodas. Used by permission of Pantheon Books.

CAUTION: Users are warned that this work is protected under copyright laws and downloading is strictly prohibited. The right to reproduce or transfer the work via any medium must be secured with Pantheon Books.