Graham Lock and David Murray,

co-editors of

Thriving on a Riff: Jazz & Blues Influences in African American Literature and Film

______________

About The Hearing Eye

The widespread presence of jazz and blues in African American visual art has long been overlooked. The Hearing Eye makes the case for recognizing the music’s importance, both as formal template and as explicit subject matter. Moving on from the use of iconic musical figures and motifs in Harlem Renaissance art, this groundbreaking collection explores the more allusive — and elusive — references to jazz and blues in a wide range of mostly contemporary visual artists.

There are scholarly essays on the painters Rose Piper (Graham Lock), Norman Lewis (Sara Wood), Bob Thompson (Richard H. King), Romare Bearden (Robert G. O’Meally, Johannes Völz) and Jean-Michel Basquiat (Robert Farris Thompson), as well an account of early blues advertising art (Paul Oliver) and a discussion of the photographs of Roy DeCarava (Richard Ings). These essays are interspersed with a series of in-depth interviews by Graham Lock, who talks to quilter Michael Cummings and painters Sam Middleton, Wadsworth Jarrell, Joe Overstreet and Ellen Banks about their musical inspirations, and also looks at art’s reciprocal effect on music in conversation with saxophonists Marty Ehrlich and Jane Ira Bloom.

There are scholarly essays on the painters Rose Piper (Graham Lock), Norman Lewis (Sara Wood), Bob Thompson (Richard H. King), Romare Bearden (Robert G. O’Meally, Johannes Völz) and Jean-Michel Basquiat (Robert Farris Thompson), as well an account of early blues advertising art (Paul Oliver) and a discussion of the photographs of Roy DeCarava (Richard Ings). These essays are interspersed with a series of in-depth interviews by Graham Lock, who talks to quilter Michael Cummings and painters Sam Middleton, Wadsworth Jarrell, Joe Overstreet and Ellen Banks about their musical inspirations, and also looks at art’s reciprocal effect on music in conversation with saxophonists Marty Ehrlich and Jane Ira Bloom.

With numerous illustrations both in the book and on its companion website, The Hearing Eye reaffirms the significance of a fascinating and dynamic aspect of African American visual art that has been too long neglected. #

*

About Thriving on a Riff

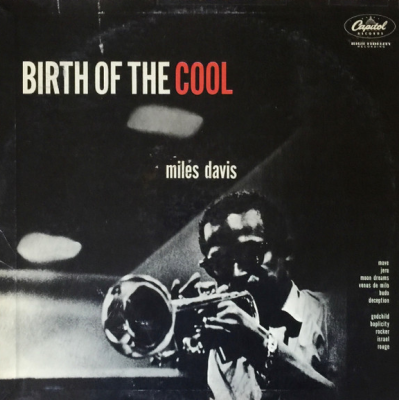

From the Harlem Renaissance to the present, African American writers have drawn on the rich heritage of jazz and blues, transforming musical forms into the written word. In this companion volume to The Hearing Eye, distinguished contributors  ranging from Bertram Ashe to Steven C. Tracy explore the musical influence on such writers as Sterling Brown, J.J. Phillips, Paul Beatty, and Nathaniel Mackey. Here, too, are Graham Lock’s engaging interviews with contemporary poets Michael S. Harper and Jayne Cortez, along with studies of the performing self, in Krin Gabbard’s account of Miles Davis and John Gennari’s investigation of fictional and factual versions of Charlie Parker. The book also looks at African Americans in and on film, from blackface minstrelsy to the efforts of Duke Ellington and John Lewis to rescue jazz from its stereotyping in Hollywood film scores as a signal for sleaze and criminality. Concluding with a proposal by Michael Jarrett for a new model of artistic influence, Thriving on a Riff makes the case for the seminal cross-cultural role of jazz and blues. #

ranging from Bertram Ashe to Steven C. Tracy explore the musical influence on such writers as Sterling Brown, J.J. Phillips, Paul Beatty, and Nathaniel Mackey. Here, too, are Graham Lock’s engaging interviews with contemporary poets Michael S. Harper and Jayne Cortez, along with studies of the performing self, in Krin Gabbard’s account of Miles Davis and John Gennari’s investigation of fictional and factual versions of Charlie Parker. The book also looks at African Americans in and on film, from blackface minstrelsy to the efforts of Duke Ellington and John Lewis to rescue jazz from its stereotyping in Hollywood film scores as a signal for sleaze and criminality. Concluding with a proposal by Michael Jarrett for a new model of artistic influence, Thriving on a Riff makes the case for the seminal cross-cultural role of jazz and blues. #

*

Book Excerpts

Out of This World: Music and Spirit in the Writings of Nathaniel Mackey and Amiri Baraka,

by David Murray

Sam Middleton: The Painter as Improvising Soloist ,

Interview by Graham Lock

_____

Interview hosted by Jerry Jazz Musician publisher Joe Maita

*

_____

“Charlie Parker is reported to have said, ‘Hear with your eyes and see with your ears.’ Who can be sure of what he meant? But perhaps it was a way of saying that African American creativity is so grounded in its music that listening will allow you to better see its paintings, to better read its poetry and fiction.”

– Graham Lock and David Murray

_______________________________________

JJM In an interview with the poet Michael Harper, Graham, you describe the aim of your books as to “look at the influence of jazz and blues on other African American art forms, and vice versa, though our main emphasis is on the music’s influence and our starting point is that it does have a special and central role in the culture.” How broad does the definition of jazz go when discussing whether or not a film, painting, or work of literature is influenced by jazz music? Is there also a boundary line to defining what is jazz-influenced in the world of art?

DM We use the word “jazz” at times in our books, and we also talk about “African American music.” In essence, we were trying to identify certain aspects of jazz and certain elements of African American music that carry over to other art forms in some ways. For instance, we would find that a work of art contained elements that people would recognize as jazz-like, such as spontaneous improvisation or certain kinds of rhythmic characteristics. So we would be looking for elements like that which carried over rather than having to recognize art that is specifically jazz-influenced.

When we were trying to determine what could be characterized as “jazz-based,” we looked for two things in particular. One was to ask how much of the subject matter is “jazz” — in other words, are they writing about John Coltrane, or is Romare Bearden painting a picture of a musician or a dancer, and how is it being represented? So, content was one level we looked at. The other level, which is somewhat more problematic, is determining how much the characteristics of jazz-like spontaneity and rhythm were brought into the art form, whether literary or visual.

GL I would add that it wasn’t really us doing the defining. I interviewed people who identified their own work as being influenced by jazz or blues, so that link had already been made by the artists themselves rather than by us trying to find a link. The same could be said about the essays in the books too. We invited people to write on the topic of jazz and blues influences in other African American art forms, and the contributors made the links. We didn’t have a predetermined set of definitions or characteristics. We were open to persuasion — and to skepticism. There’s a great piece by Michael Jarrett in Thriving on a Riff that questions the received wisdom on how these kinds of cross-genre links actually occur. He makes the point that changes in technology and media can change the way influence itself operates.

JJM What are the earliest links between African American painting and music?

GL The short answer is I don’t know for sure. There is a painting from the 1890’s by Henry Ossawa Tanner called The Banjo Lesson, which I think is one of the earliest African American paintings to have some musical content. But in terms of jazz and blues actually having an influence on art, this would probably have been in the 1920’s, in the work of painters like Aaron Douglas and Archibald Motley.

DM And you could say the same thing on the literary side. While there are accounts of jazz music going back to the end of the 19th century, it wasn’t until the 1920’s that artists and writers took jazz themes and tried to compose them artistically. That was when they made this a part of the way they work.

JJM You wrote, “It is no surprise . . . that the music has played a crucial part in African American visual art. What is surprising is the continuing neglect of this association, and of African American art in general, by both the academy and the commercial art world.” Why has this association been neglected? Is it a simple matter of racism?

GL I think it’s clear that racism has played a significant part in the exclusion of black artists from art galleries, and that is certainly the impression I got from talking to black artists. For instance, Vincent Smith, who started painting in the 1940’s, told me in 2003 that the art world in the States was the last bastion of white exclusivity. Several other people that I spoke to said the same sort of thing. On the other hand, there are more African American-run galleries now, as well as an increasing number of African American scholars and curators who are writing about black art, so I think the situation is beginning to improve in the States. However, there is still no wider public appreciation of black art, either in the United States or in Europe, and this neglect extends to the academy too. One of the reasons we did The Hearing Eye was that we couldn’t find any information about jazz and blues influences in African American art — all the books on music and art we looked at dealt almost exclusively with Western classical music and European art.

DM It could be that people allow racial groups praise for particular things they do well, so, African Americans are praised for “being musical,” it is their “privileged form,” so to speak, and they are not given credit for their work in other art forms.

[Norman] Lewiss racial identity, and the signifiers of African American experience that he wove into his canvases, not only challenged the implicit whiteness of abstract expressionisms supposed universalism but also served as a reminder that, to large numbers of African Americans, freedom itself was itself still an abstract concept in the United States.

– essayist Sara Wood

[/infobox]

JJM There is an interesting essay in your book about black artists who rely on folk materials — like jazz music — and leave themselves open to racial stereotyping.

GL Yes, I guess you’re thinking of Rose Piper, who did some fantastic paintings in the 1940’s based on blues recordings. But she was wary of people’s assumption that this kind of “black subject matter” was all that she, as a black artist, was supposed, or even able, to do. The contemporary collagist Sam Middleton makes a similar point in the book — he loves jazz and has featured it in much of his work but then felt he had to abandon it for a period. He said people were expecting him to paint jazz-related canvases just because he was black. So he quite deliberately began to focus on other kinds of subject matter, from seascapes to classical music, which he also likes.

I think it’s been true of particular styles of painting as well. Black artists have often been “allowed” to paint in the social realist style, whereas they have been excluded from the abstract art canon, which is absurd, because there have been some terrific abstract artists among African Americans — Norman Lewis, for example, who to my mind is among the major figures of the last 50 years, as is Joe Overstreet. There seems to be an expectation that black artists should be confined to painting in a certain way and about certain things, and if they stray outside of that, they are likely to be ignored or heavily criticized. It reminds me of what Anthony Braxton has said about jazz, that it is a zone in which black performers are allowed to play, but if they try to do any other kind of music, like opera or symphonies, they get hammered by the cultural gatekeepers.

JJM Yes, and this was certainly true of the boundaries Hollywood once imposed on African Americans. They could be in a film as long as they expressed the characteristics of ignorance and fear and laziness. It is also well known that scenes depicting integration were cut so the film could be shown to a southern audience. So, there was a real consistency across all art forms about what type of art African Americans could participate in, and within what boundaries.

DM That’s right.

*

Monk taught me not to be afraid to take a chance, not to be afraid of making a mistake. Duke Ellington taught me that within the bounds of the thirty-two-bar song, you can weave colors but within a discipline. Louis Armstrong taught me a sense of humor and the pride to have while working. Your work is the interpretation of your free spirit, if you have one. Coltrane taught me you were permitted to go as far as you want to go as long as you remember the principle you started out with.

painter Sam Middleton

*

JJM To what extent did jazz music and the blues guide artists’ experiments with abstraction?

GL It’s curious that Jackson Pollock is often associated with free jazz, I guess because Ornette Coleman used one of his paintings on the cover of the Free Jazz LP. But in fact Pollack predates free jazz. As far as we can tell, he was a big fan of swing and New Orleans jazz.

I don’t think you can draw up rules about this, because it seems to me that these artists, whoever or whatever their influences, are all influenced in very different and personal ways. The artist Joe Overstreet — whose Storyville series of paintings is partly influenced by New Orleans jazz and by his admiration for Louis Armstrong — said that he experimented with putting paint on newspaper, and then putting the newspaper onto the canvas, and this technique felt right to him for those particular paintings because he realized the texture that he got from the paint on the canvas reminded him of the texture of the music. That seems to me to be a very specific and personal kind of influence, to do with how he heard the music, and in lots of cases, influence works in this extremely subjective way.

DM This is one of the things that our project generally found, that individual artists work in different ways. It was never very clear that they would compose while listening to the music, and in very few cases did we come across any really direct sense in which they were being inspired somatically to paint in a particular way. It would be nice to think that Jackson Pollock was listening to Ornette Coleman as he was painting, but as Graham said, he was listening to much earlier and less “free” music. So while there is a general feeling that these freewheeling paintings are influenced by some sort of freewheeling jazz, it is quite hard to pin down.

JJM Richard King, one of your collection’s essayists, wrote that “It is not painter Bob Thompson’s choice of subject matter but his way of handling color and structural-spatial arrangements that were jazz influenced.”

GL This idea of jazz and blues impacting on the formal aspects of art is really intriguing to look at because, as Dave says, it is so slippery and subtle. Just thinking about it now, for example, there does seem to be some kind of recurring link between abstraction in art and musical influence. I’m thinking, for example, of the way Sara Wood, in her essay on the painter Norman Lewis, could link his interest in bebop with his approach to abstract expressionism. There is also a very interesting relationship between the figurative and the abstract in the work of, say, Joe Overstreet or Rose Piper, which may be linked in some way to the influence of the music.

JJM How do the paintings of Rose Piper reflect the “sound” of the recordings she named her paintings after?

GL Well, I try in The Hearing Eye to suggest a few possibilities. It’s all speculative, because by the time I was able to talk to Rose Piper, her memory had deteriorated so badly that she was unable to remember the paintings themselves, let alone the recordings that had influenced them. But in her Back Water canvas, for example, which we know was partly a response to Bessie Smith’s “Back Water Blues,” the foreground figure of the young woman perhaps corresponds to the voice of the singer — in terms of its dominant presence, its somber tone, et cetera — while the painting’s busy background of swirling waters and floating debris can be compared to the animated piano that James P. Johnson plays on the record.

In Piper’s slightly later, semi-abstract canvases, the correspondence is less literal and more elusive. I would liken her distortions and exaggerations of the figure, as a means of depicting heightened emotions, to the blues’ use of vivid hyperbole for the same reason, whether it’s about sitting on top of the world or pouring water on a drowning man. There’s a kind of stylized quality to the blues, a combination of terseness and exaggeration, which I think is akin to the semi-abstraction of the art.

*

African art is like the blues; you know, when a blues musician sings a line, hell sing it twice but hell do something different with it the second time. He won’t repeat the same thing. If you look at African art, its never the same; it looks the same but it never is, its more free, what we call free symmetry, and African music is like free symmetry.

artist Wadsworth Jarrell

*

JJM Essayist Robert O’Meally wrote that painter Romare Bearden “approaches his subjects not as a portrait painter might, or a landscape artist . . . but in the manner of a jazz musician.” He went on to talk about how you can understand jazz music’s aesthetic values in Bearden’s work, and how the process of making art is “jazz-like.” I think it goes back to what we were saying about where an artist gets his or her inspiration from, and what their process is. How these art forms are all interconnected is what makes this topic fascinating…

DM While there is agreement that there are connections, they are as different as the artists themselves, and difficult to pin down. What we consistently find in all of the essays, as well as in everything that we write, is that we all want to make these connections, but as soon as we do we find that they are very tenuous, and very difficult to actually specify or define. In what sense is the art we write about “jazz-shaped” or “jazz-like”? As you say, that is one of the fascinating things about this.

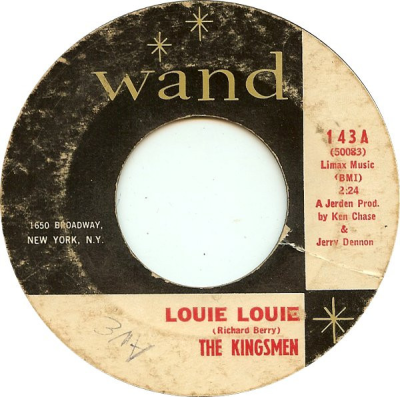

GL I think it was one of the impulses behind the books, to explore these cross-genre relationships in more depth. People had been aware of links between jazz and painting or jazz and poetry but tended to write about them in rather vague terms, invoking notions of spontaneity, improvisation and so forth, yet it’s a lot more complex and interesting than that. For instance, there’s a great essay in The Hearing Eye by Johannes Völz that asks, what about the role of the viewer in this cross-genre influence? If you’re looking at a canvas that’s “jazz-influenced”, how is that influence perceivable? How do you see it? How do you “hear” it? And how does that visual experience compare to listening to the music? So the focus is not only on tracing the musical influence on the painter but on the viewer too. We also look at other visual art forms. There are chapters on the photographer Roy DeCarava and the quilter Michael Cummings, and there is Paul Oliver’s survey of the graphic art in early advertisements for blues records — these are all fascinating areas.

JJM This fascination carries over into film as well. There were several interesting essays in your books concerning the films that can be considered “jazz-related,” as well as the music written for them.

DM One of the interesting things about working on the film portion of Thriving on a Riff was that, in most cases, we were writing about African American writers and artists who were working in a white-produced and white-directed Hollywood studio system. They worked within a “white agenda.” To some extent you could say that the treatment of jazz in film is different than in art because it is often already hedged about and censored when it appears in films in a way that art by an African American artist or writer is not. The influences come through more channels, and they come more disguised or controlled.

JJM What is an example of a film that is “jazz-related” without it being a film on jazz or a jazz personality?

GL Mervyn Cooke contributed an essay about Anatomy of a Murder, which is an example of a film whose content didn’t have much to do with jazz, but with a film score by Duke Ellington, the music is likely to be jazz-related. The question then becomes, how is this music being used in the film?

DM We considered going into the direction of looking at jazz influences in experimental film, where directors like John Cassavetes deliberately use film to try and be improvisatory, where they create an experimental interface between the music and the film. Well, in a way, the films our contributors have chosen to write about are not that sort of film. They are more about how jazz found its way into film rather than being primary.

JJM How did the growing acceptance of jazz as an art music change the way jazz music was used in Hollywood?

GL I am trying to remember what Mervyn Cook said in his chapter, where he talked about symphonic jazz becoming popular in the 1950’s, and how that affected the way jazz was used in Hollywood. I think his argument is that it had a modernizing influence in terms of the film score, even though many jazz fans and critics did not like symphonic jazz per se.

DM It also raises a question, when you say “the growing acceptance of jazz,” because, in what way? Because jazz was an increasingly accepted form of popular entertainment, but when you look at film scores, they attempted this classical sound in a grand attempt to get jazz in an orchestral version . . . I suppose at that point, that becomes available, and it is on the palette of the composers who write a film score.

GL I also wonder about the influence of bebop in this area. The idea of bebop musicians presenting themselves as artists rather than as entertainers, which had been the case in the past. I think that would have had a broad impact. It would have made people at least think about that topic. Although, as David Butler points out in his chapter on John Lewis’s score for Odds Against Tomorrow, very few black composers were given the chance to score films by the major Hollywood studios and that situation didn’t change very quickly.

JJM Bebop was all part of the modernist movement, and I am sure there was a comparing of jazz music — that was now being looked at as a modernist art — with modernist film. If you look at how Elmer Bernstein was using jazz, it was elementary compared to the way John Lewis used it in his film. Bernstein admitted to using jazz music in some of his films as associating it with sort of unsavory characters. One of the films, Walk on the Wild Side, was set in New Orleans in a house of ill repute, so he sort of connected jazz to this sleazy component, whereas John Lewis, in Odds Against Tomorrow in 1959, looked at it as a modernist would, and communicated from that perspective.

DM Certain instruments, especially the saxophone, were used by filmmakers as a way of implying a link to sex or it does have this, as you say, association. The saxophone would often be used quite easily as sort of implying a link to sexiness or transgression.

*

Were born into a society that has inherited all sorts of prejudices racial, religious and even musical, and this one concerning jazz, like most prejudices, has its roots in truth or reality at some point It is a subtle prejudice and I find myself fighting it within myself. The times Ive used jazz to color my music have been in films with sleazy atmospheres The Man with the Golden Arm was about narcotics, Sweet Smell of Success dealt with some very unsavoury characters in New York, and Walk on the Wild Side was largely set in a New Orleans house of ill repute. So Im guilty, although I dont think its necessary to use jazz in this way. Its simply something that is very difficult to avoid.

– Elmer Bernstein

*

JJM How does film music play a role in a film’s racist or anti-racist concerns?

GL Well, the essay by Ian Brookes on To Have and Have Not examines how the director Howard Hawks uses jazz to underscore the film’s anti-fascist stance. (It’s set in Vichy-controlled Martinique during World War II.) As Ian shows, Hawks does this in several ways, from a simple shot of black and white musicians playing together, to the band quoting “Limehouse Blues,” which has various levels of signification since it brings to mind Django Reinhardt, which reminds us of the Nazis’ anti-gipsy policy, which in turn reminds us of their other racial policies. And the implicit anti-fascism of the integrated band also had a message for American audiences, of course. Hawks apparently agreed with Sterling Brown that jazz is an inherently democratic form and Ian not only examines how this affects the way Hawks deployed the music, he also suggests that it influenced Hawks’s own working methods in making the film.

In terms of a film’s racist concerns . . . It’s not quite the same thing, but there’s an extremely interesting essay in Thriving on a Riff by Corin Willis that looks at the strategies Hollywood employed to undermine the impact of black musical performance on screen. Basically, he’s saying that minstrelsy was given an extra lease on life because several of its techniques were adopted by Hollywood to contain the power of African American popular music. This may help explain why the jazz presence in film has been so circumscribed compared, say, to its presence in literature.

JJM There are a wealth of writers who were influenced by jazz, among them Langston Hughes, James Weldon Johnson, Amiri Baraka, Albert Murray, Ralph Ellison, Jack Kerouac . . . Poetry and jazz has long been connected, and so often John Coltrane is the centerpiece of a poet’s work, including one of the poets you interviewed, Michael Harper.

DM It is really noticeable how many poets write about Coltrane, enough so that it is almost a genre in its own right. Critics like Kimberley Benston have written entire chapters about Coltrane poets.

GL I think it is partly attributable to the achievements of Coltrane himself. He was such an outstanding figure. His peak years coincided with the rise of a black nationalist consciousness — black power — and a heightened cultural awareness within the African American population.

DM It is interesting because a comparable figure in jazz music is Charlie Parker, who gets coverage and significance in musical terms but the writers didn’t pick him up in quite the same way as Coltrane. He appears in disguised forms, for example as a doomed jazz musician in James Baldwin’s work. Ralph Ellison was the most prominent African American writer of the 1950’s and 1960’s, but he was not a fan of bebop — of Parker’s music. So, Parker didn’t get that coverage so directly to the same degree as Coltrane, although he does in graffiti in the famous phrase “Bird Lives.” But it is noticeable that the great writers didn’t look at him in that way.

JJM Coltrane was such an inspiration to the black arts poets and the black arts movement, who looked to jazz musicians for inspiration in general, but in particular, Coltrane represented musical freedom. Black arts poets must have admired him for that alone…

DM I suppose the writer who gives a wide range of discussion in that sense is Amiri Baraka, who we can find covering all the periods of jazz and who took the longest look at this subject.

GL I have a somewhat cynical comment to add here. Coltrane’s popularity with poets may have been in part because, once he’d died, they could write anything they liked about him. They could use him for their own ends, as it were, and he couldn’t answer back. Of course, after the vicious criticisms that had been heaped on him by some of the white jazz press, you can understand why black poets wanted to valorize him — and often in militant terms that Coltrane himself would probably not have endorsed. It’s also the case that he died at the height of his achievements. There’s no knowing what he would have done with his music had he lived longer, or whether it would have been as well received.

DM As you would expect, the poems about Coltrane vary so much in style and quality. There are poems in which he is the subject — they could be elegies or whatever — and other poems are designed to try to recapture the sound of his instrument, where poets experiment with language to try to close the gap between language and music. So, the poetry is in the range of writing about Coltrane, trying to be him, and trying to exemplify him in the structure of the composition itself.

The other question, of course, is the question of the quality of the writing. One of the thorniest areas in literature and music, it seems to me, is poetry and jazz. The overlap between poets and musicians should work, but so often it doesn’t, because if you look at the many attempts of putting the poetry and jazz together, you will find some really bad poems out there.

JJM Jazz is a difficult subject to turn literary. So often the results are very corny and feel forced…

DM Exactly. I know we found some good ones to publish, but there are so many more bad ones. You find one and believe it to be a worthy attempt, but both the musician and the artist seem to be constrained, or the art is not coming out in the best way.

*

Contemporary American poetry is vitally interested as many poets are personally interested in two of the central principles of the jazz art: improvisation and voice, and that these two principles point “toward yearnings in poetry often yearnings away from the printed page that make jazz the land of hearts desire.

– poet Charles O. Hartman

*

JJM Which poets have been successful in combining the compatibility and tension between the language and jazz?

DM Jayne Cortez is a poet with musical credentials, and who has performed with very serious musicians. She is an example of someone who explored this, although people would have differing views about how successful she was within the form. Amiri Baraka is another one who comes to mind.

GL I think Langston Hughes and Sterling Brown were pioneers in this area. In Thriving on a Riff both Steven Tracy and Michael Harper talk about Sterling Brown’s interest in blues and jazz and how he incorporated those influences in his poetry, although as far as I know he didn’t perform with musicians to any great extent. More recently, Michael Harper himself would be a prime example of someone who can make this happen, for instance in his collaborations with bass clarinetist Paul Austerlitz — some examples of which we have on the Riff website.

DM Yes, and Nathaniel Mackey, who writes fascinatingly about it in his critical essays, and also in his novels, which are based around the idea of a jazz band. I think he really does explore the interface of the two forms, and is one of the people who pushes it theoretically the furthest. He performs his work with jazz musicians as well. It is a tricky form, no question about it.

JJM You talked earlier about how poets would try to adapt their poetic style to reflect the music of Coltrane. Is it even possible to successfully mimic jazz music with poetic language?

DM When I encounter poems where the poetry is, for example, broken up in lines in an attempt to get the rhythm of somebody like Coltrane, I don’t know how to read them. There is a sense in which they are a different media, and this is one of the challenges we have, isn’t it? The more one media tries to imitate the other media, the more constrained it becomes. The most interesting work is often the work where this is a relationship, but I can’t quite pin them down. The poetry looks bleak when simulated.

GL I talked to Bill Dixon about the issue of poets writing about Coltrane (although this isn’t in the book). He knew Coltrane quite well, I think, and his view is that all the poets who wrote about Coltrane were basically parasites who tried to jump on the Coltrane bandwagon. His argument is that the poems were grossly inferior to the music they referenced. I’m not sure I agree with him entirely, and certainly not with regard to poets such as Jayne Cortez and Michael Harper, but I think in some cases what he says is probably true.

In Thriving on a Riff, there’s an essay by Bertram Ashe on the contemporary writer Paul Beatty, whose novel Tuff includes a satirical portrait of an ageing black nationalist poet — this guy and his friends are always banging on about Coltrane, much to the disgust of his son, who says their “bullshit poetry” has turned him off the music and is probably killing Coltrane’s record sales! So I guess there’s been a backlash by a younger generation of black writers, who don’t buy into the idolatry or the rhetoric of that kind of poem.

DM One of the things I noticed while working on the literary section of the book is the feeling that, because jazz music holds such a privileged position within African American culture, invoking its name or to make a reference to blues culture within the work creates a credibility or a sense of racial identity. So it becomes a sort of “name dropping” or a bowing to tradition that can come up empty in some cases.

JJM What does jazz-influenced art, literature and film teach society about life?

GL I’m not sure how to answer that question. Speaking for myself, working on this project has taught me that there’s so much great art out there — by which I mean painting, literature, film, whatever — that still isn’t getting the recognition or the level of attention it deserves. Exploring the work of fantastic painters like Norman Lewis and Joe Overstreet and fantastic writers like Sterling Brown has been hugely rewarding for me. I hope everyone who reads these books will find something that’s equally rewarding for them.

___________________________

Plunge into the very depths of the soul of our people, and drag forth material, crude, rough, neglected. Then lets sing it, dance it, write it, paint it. Lets do the impossible. Lets create something transcendentally material, mystically objective. Earthy. Spiritually earthy. Dynamic.

– painter Aaron Douglas, in a letter to Langston Hughes concerning the need for African American artists to develop an aesthetic that is not merely white art painted black.

____

*

The Hearing Eye: Jazz & Blues Influences in African American Visual Art

Thriving on a Riff: Jazz & Blues Influences in African American Literature and Film

*

Book Excerpts

Out of This World: Music and Spirit in the Writings of Nathaniel Mackey and Amiri Baraka,

by David Murray

Sam Middleton: The Painter as Improvising Soloist ,

Interview by Graham Lock

*

About Graham Lock and David Murray

Graham Lock is a freelance writer, Special Lecturer in American Music, University of Nottingham, and author, Forces in Motion: Anthony Braxton and the Meta-reality of Creative Music, Chasing the Vibration: Meetings with Creative Musicians, and Blutopia: Visions of the Future and Revisions of the Past in the Work of Sun Ra, Duke Ellington and Anthony Braxton, and editor, Mixtery: A Festschrift for Anthony Braxton.

David Murray is Professor of American Studies, University of Nottingham, and author, Indian Giving: Economies of Power in Early Indian-White Exchanges, Forked Tongues: Speech, Writing and Representation in North American Indian Texts, and Matter, Magic and Spirit: Representing Indian and African American Belief.

_______________________________

Graham Lock and David Murray products at Amazon.com

_______________________________

This interview took place on March 14, 2009

*

If you enjoyed this interview, you may want to read our conversation with art historian on Alfred Appel

# Text from publisher.

thank you for keeping the essence in the words-a long time gift of chasing the vibration, that keeps their heart alive beyond their art.

best regards

geraldine eguiluz