.

.

In a 2014 Jerry Jazz Musician interview, the late jazz writer and cultural critic Stanley Crouch shares his thoughts on Charlie Parker, the great genius of modern music…

(Click here to visit Mr. Crouch’s Wikipedia page)

.

.

___

.

.

photo by Michael Jackson/jackojazz.com

Stanley Crouch

___

.

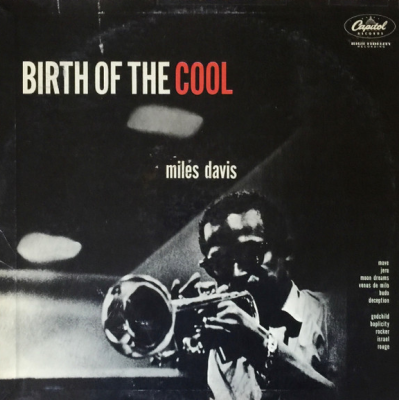

Described by the New York Times as a “bebop Beowulf,” Stanley Crouch’s Kansas City Lightning: The Life and Times of Charlie Parker is a love song to the life and times of Bird, one of jazz music’s most critically important figures. Mr. Crouch, himself an essential participant in both contemporary criticism and in the delivery of live performance (through his work with Jazz at Lincoln Center), discusses his long-anticipated biography with Jerry Jazz Musician in a recently conducted interview.

Kansas City Lightning: The Rise and Times of Charlie Parker is the first installment in the long-awaited portrait of one of the most talented and influential musicians of the twentieth century, from Stanley Crouch, one of the foremost authorities on jazz and culture in America.

Throughout his life, Charlie Parker personified the tortured American artist: a revolutionary performer who used his alto saxophone to create a new music known as bebop even as he wrestled with a drug addiction that would lead to his death at the age of thirty-four.

Drawing on interviews with peers, collaborators, and family members, Kansas City Lightning recreates Parker’s Depression-era childhood; his early days navigating the Kansas City nightlife, inspired by lions like Lester Young and Count Basie; and on to New York, where he began to transcend the music he had mastered. Crouch reveals an ambitious young man torn between music and drugs, between his domineering mother and his impressionable young wife, whose teenage romance with Charlie lies at the bittersweet heart of this story.

With the wisdom of a jazz scholar, the cultural insights of an acclaimed social critic, and the narrative skill of a literary novelist, Stanley Crouch illuminates this American master as never before. (# text from publisher)

On November 22, 2013, Crouch joined Jerry Jazz Musician publisher Joe Maita for a conversation about his book.

.

.

___

.

.

photo by William Gottlieb/Library of Congress

Charlie Parker at the Three Deuces, New York; c. August, 1947

.

“To [bandleader Jay] McShann, Parker seemed to have a crying soul, a spirit as troubled by the nature of life as it was capable of almost unlimited celebration. But the saxophone was all he really had: it provided him with the one constantly honest relationship in his life. What he gave the horn, it gave back. What it gave him, he never forgot.”

– Stanley Crouch

.

__

.

JJM In the acknowledgement section of your book you wrote, “I can reconnect with my entire family, all of my neighborhoods, everything I’ve ever done or imagined, whenever I hear any jazz band heat up and ‘put the pots on,’ showing how well it can struggle for joy together. No art says ‘I want to live’ better or more forcefully than jazz. From the whisper, to the mysteriously artful noise, to the exultant and affirmative cry or scream, ever unwilling to be held down, every page of this book is a testament to that.” In addition to being a terrific biography of a historic musician, this book seemed like a very personal endeavor – a labor of love. When did you first conceive of this book?

SC I began to conceive it after Clint Eastwood — whom I respect and admire as a director in more cases than not — made what I felt was an extremely bad movie called Bird, in which I didn’t see the Charlie Parker whom I knew of or had heard of. I saw Forest Whitaker playing Charlie Parker, and I saw an actress playing Chan Parker in a role of importance far beyond what she actually had in life. In fact, when I did interview Chan the story she told about herself and Charlie Parker was much heavier than the one that they had on the screen, which was the story of the unfortunate woman captured in a marriage with a guy who is a heroin addict, which was definitely true, but she told me many things about Charlie Parker that were not in the film or in the screenplay perhaps — and these were things that wouldn’t have taken long to communicate to you but they weren’t there.

JJM Much of the primary source material you used for the book consisted of interviews that were conducted in the early 1980’s with many of the people — long since deceased — that had touched Parker’s life personally and professionally, including the musicians Buster Smith, Jay McShann, his mother Doris Parker, and his first wife Rebecca. Who was your most valuable resource from among the people you interviewed for the book?

SC Well, in a certain sense Rebecca Ruffin — which was her maiden name when she married Charlie Parker when he was 16 and she was about 18 — was the biggest find for me. She told me many things about Charlie Parker and about Kansas City and how it felt and the way people actually lived during that period. This broke free of a lot of stereotypic and statistically purported information about the lower class during the depression, because, what I call in the book “heroic optimism” was very fundamental to the way that the people looked at life during that period. And, Rebecca’s description of her own graduation and Charlie Parker coming to the reception to see her and dancing all night with her was a very big deal to me because it added a kind of teenage romance to the Charlie Parker story that was not imagined by me before. It made me realize that Charlie Parker and Rebecca Ruffin were just like all American teenagers who had a romantic Mickey Rooney/Judy Garland sort of teenage experience. That kind of human quality of Charlie Parker’s life is what I was actually most interested in because I don’t think we get much of that from other books about Charlie Parker.

JJM Rebecca shared a very personal story with you about the time she discovered Charlie was using drugs. It was really sad and somewhat painful to read, honestly. What was it like for Rebecca to tell you that story?

SC Well, the first thing is that when you’ve interviewed a lot of people your ear kind of gets tuned to whether or not they’re telling you the truth or whether they are making up what is today called “urban legends.” I could tell that what she was telling me actually happened, not only by the way she looked but also because she tended to talk in the first person. That world was extremely alive to her, and in the instance you bring up, she describes it by saying, “Charlie’s upstairs. He calls me, and I go upstairs. I open the door and I go in, and Charlie tells me to sit on the bed.” She then describes herself as seeing him shoot-up the drugs — he took one of the ties hanging on the mirror, put it around his arm, and then he shot up the dope. She then got scared, gets the kit that the drugs came out of and then took them to his mother. The story goes on from there.

But at that point in the book I wanted to tell her story in a very straight way that was not melodramatic and didn’t use a lot of adjectives, because the power is in what actually happens. One of the things that Hemingway taught American writers is that some things are felt stronger when you get out of the way of the story. The feeling you got while reading the story was what I hoped readers would experience — as if they were standing right next to Rebecca, seeing this happen — and not as though it were “Stanley Crouch telling us how horrible it is that Charlie Parker was beginning to use drugs.” It’s a feeling of actually seeing it and responding to it.

JJM What this story demonstrated very clearly is how his drug use affected those who loved him, and that’s something that you don’t really think about when you’re engrossed in his greatness as a musician. We know how the drugs impacted his life, but they also devastated important personal relationships with his wife, mother and son. Did Rebecca indicate to you what Parker’s mother Addie may have done to help him with his addiction?

SC Well, his mother was dead when I began the book so I couldn’t find out what she did, but Rebecca did everything she could do, and she became accustomed to the life that Charlie Parker began to live after he became addicted. There’s much detail in the book about the shift in his life that came about, and also about the resolve that Rebecca had to be a strong wife — she understood that she was in a very terrible situation and so was he, but at that particular point she didn’t feel that she should abandon him or abandon their marriage. She just felt that she should figure out how to live up to the problems that they were faced with, and I think that in today’s atmosphere of constant self-obsession and ideology Rebecca Parker would not necessarily be understood because the empathy that leads to what is dismissed as self-sacrifice today would not actually be understood.

JJM You describe Parker’s father as “an incorrigible whisky head who left home when Parker was nine.” Did he have any contact with his father after that?

SC He didn’t have any that Rebecca saw except that his father turned up at their reception after they got married. She said that no one would actually know what Charlie Parker was doing or what he and his mother were doing unless they wanted you to know. So we don’t know how much Charlie Parker saw his father or how much time his father took visiting him or how many places his father took him to and how much time his father spent with him when he was a younger guy. But we do know that on the day of his marriage to Rebecca his father turned up, and she saw him and she describes him, and talks about how she could tell what kind of work he did by the way his shoes were polished. She explained that he was a charming, good-looking guy like his son.

JJM Who were the influential adult male role models during Parker’s youth?

SC Buster Smith was a very big influence as a saxophonist and also the way he carried himself, which is described in the book by Orville Minor, Clarence Davis and Jay McShann. They all remembered Buster Smith very vividly because he was the guy who didn’t constantly pat himself on the back as a highly respected jazz musician could have. Orville Minor describes him as always being a shirt-and-tie guy who didn’t talk a lot of “stuff.” He was interested in talking about things that were going on in the world, and about the culture of America. So, he did all that, and he could play so well that people felt that they should call him “Professor Smith.” As Orville said, “If you didn’t believe that he was a professor, if you were on the bandstand with him you found out very quickly that he was because he was ‘bad’ on that saxophone. You would say, ‘Oh, well, he does know a lot of music.'”

Charlie Parker was mentored by Buster Smith and he was the kind of guy, like most young guys, who picks up as much as possible from an admired influence as they can. So the way Charlie Parker spoke, and given his interest in the world, I’m sure he got those things from being around Buster Smith because he would ask questions a lot. If he was around Buster Smith, who liked him and knew he was very talented, he would have told him things that he asked him about Smith himself, and about Smith and Lester Young and some other members of the Blue Devils hoboing back to Oklahoma City after being stranded in the early 30’s during a tour of the East Coast.

Some naïve people who reviewed the book didn’t understand why I wrote so much about Buster Smith, but they didn’t realize how connected he was to Charlie Parker. He was connected to him as a saxophonist and as a person, and as Buster Smith was telling me about his life I’m sure it was a life he told Charlie Parker about.

JJM Parker actually called him “Dad” at times…

SC Yes he did.

JJM On Kansas City, where Parker grew up, you wrote “It was a city where corruption sprawled in comfort and a child could get the idea that right was wrong and wrong was right; the mayor was a pawn, the city boss was a crook, the police were corrupt, the gangsters had more privileges than honest businessmen, and the town was as wild with vice as you could encounter short of a convention of the best devils in hell.” How did this environment help shape the decisions Parker would make?

SC Well, the ongoing irony of that much corruption is that you could also have an artistic community that Mary Lou Williams herself described as “heavenly.” She described it as a “heavenly city” because a musician could actually play all of the time, and Charlie Parker, Buster Smith, Lester Young, Gene Ramey, Jay McShann and all of these guys developed from playing their instruments all of the time in all kinds of situations, in all kinds of styles, all kinds of tunes and in all the keys. They learned how to improvise on the spot, and they learned how to deal with modulations — the changing of the keys. They went through all this stuff all the time, all day.

They could play jazz at night, and then go out to the jam sessions, and they could end up in the park with a bunch of other musicians. Eventually, Charlie Parker would be sitting there on the bench by himself, still playing the saxophone until he felt that it was late enough in the morning for him to go get the other musicians and wake them up and play some more. So this was why all these guys could play and that was where their reputations came from, because they met the challenge of improvising, making sense on the spot, figuring out how to handle all the notes that were going on around them, and how to make artistic objects at high speeds. All of those beautiful melodies that Charlie Parker was able to play are the result of the kinds of decisions that he learned to make, and he learned how to fit in.

Sonny Rollins told me once that a musician can practice by himself a lot — as they do — but one long night on a bandstand will teach you many more things than you can learn by yourself because you’re playing different songs, you’re playing with different sets, you’re playing in different keys, and you’re playing different emotions that all get worked out on the bandstand. Kansas City was that kind of atmosphere, all the time.

JJM You point out in the book that the saxophone was central to the sound and character of Kansas City jazz…

SC Oh, without a doubt, and Kansas City musicians loved to bushwhack musicians from the east coast who thought that they were going to come through this “country-boy-town” and stomp all of the local guys like they were grapes being prepared for wine. But usually, when they came to Kansas City they ended up playing the role of the grape, not the local guys. Buster Smith describes in the book how Chu Berry started playing “Body and Soul” at medium tempo and then played all those combative and advanced chord changes. Lester Young and all these other guys heard that and slipped out of that club quickly, and then Buster Smith stood up and said, “I told you all not to mess with that man!” They weren’t invincible by any doubt, but…

JJM There’s a great story you tell in the book about Benny Goodman coming through Kansas City and challenging Buster Smith on stage at one of the clubs. Someone described it as if Smith “chewed him up and spit him out.”

SC Yes, Jay McShann told that story.

JJM A well-known story in Parker’s biography is the time that he decided to test his mettle on the bandstand of tenor saxophonist Jimmy Keith, in which his playing caused the musicians to laugh him off the bandstand. In a 1950 interview with Marshall Stearns, he said that they “laughed so hard it broke my heart.” How did this event change Charlie Parker’s life?

SC Well, it made him confront what every jazz musician has to confront at some point, which is finding out how much he knows and how much he does not know, and Charlie Parker thought he could play but he actually couldn’t play. Bassist Gene Ramey was there the night that they laughed at him and threw Charlie Parker off the bandstand, and he said they talked about how Parker got turned around in the song and didn’t know where he was, but that he would figure it out, and that they weren’t going to stop him forever.

JJM It was a real turning point in his life because a lesser man probably would have quit after having this experience. Instead it may have revealed his true character…

SC You’re absolutely right. That was the point in which he decided how good he was going to be. Now anybody could have said, “I am going to become the best saxophone player in the world,” but doing it is a little bit harder than saying it, and Charlie Parker was prepared to do whatever he had to do to become the best saxophone player in the entire world, and he did become that in a very short time.

JJM It was important to him to be a great saxophone player, but he also wanted to be different. He wanted to stand out.

SC Oh, yeah. Well, he couldn’t get the kind of recognition he sought if he didn’t have something that was unique to him. All of the people he admired — people like Buster Smith, Lester Young, Chu Berry — were musicians who had something very unique about their playing, and he sought that uniqueness in his own playing. As we know, he finally got it.

JJM You wrote that Parker “worked for everything he got, and whenever possible, he did that work in association with a master.”

SC Well, he sought these masters out because one of the things that all of them had in common was an ability to create on the moment a sound that reflected their personalities. Roy Eldridge’s approach to the trumpet couldn’t be argued with because he could play so much trumpet and he was so unpredictable as a player. Chu Berry was the same kind of player, and clearly Lester Young was the same kind of player, and Buster Smith was the same kind of player. They didn’t play the same styles even vaguely, but they all had this uniqueness about themselves that they had discovered through practicing at home and improvising in public. They all had what today is called a very strong work ethic — they worked very hard on their instruments and on knowing harmony and on knowing all kinds of different ways to get through different problems on the bandstand until they could consistently do it on a startlingly good level. That was what they wished for and that was what they fought for and that was what they ended up having.

JJM Parker’s drug use is such an important part of his biography. When did he begin to notice, as you write, that his appetites “were larger than those of others, that he started to sense that he was somehow a danger to himself.”?

SC Well, he told Doris Parker that he got so far into the nightlife that he would at times stay up and take Benzedrine so he could play and continue to practice, and then take some more so he could continue to play and practice. He was so immersed in the idea of practicing and learning more music that he would disappear, to the point where his mother would have to go out and find him. She would get him home, which he was grateful for because, as he told Doris, if it hadn’t been for her he might have just never come home at all. So it was at that point that he began to become aware of the fact that he was endangered by his appetite.

He would be gone for three or four days, his mother would go find where he was, she would bring him home, he would take a bath, eat, and then he would sleep for two or three days in a row, and then he would get up and go back out for two or three or four days. So that was the life he was living at around age 17 and 18.

JJM So, was he living clean when he left for Chicago, and then to New York?

SC Well, I learned that he was through Bob Redcross and Biddy Fleet. When Bob encountered him in Chicago he wasn’t using drugs, and Biddy Fleet got with Parker when he came to New York, and he said he wasn’t getting high then either. So it’s fairly obvious to me that he had kicked the habit before he hopped a train to Chicago, and again after he hopped a train to New York. What he learned from Buster Smith, I am sure, is what kept him from making the kind of mistakes that an impressionable young guy could have made, which was to put himself in absolute danger as a drug addict on the road, hopping trains with no connections to any new drugs, and also running the danger of encountering what they call the railroad dicks, who were the police who worked there with clubs and who would beat up the bums. So, Charlie Parker avoided all of that by simply controlling his habit.

Doris Parker told me that people always thought of Charlie Parker as being weak, but she said he wasn’t weak because he was able to kick the habit by himself many times. The environment kind of overwhelmed him because there was so much dope around and so many people thought they were doing him a favor by giving him free drugs after he became very famous, which they didn’t do when he wasn’t famous. So, he was very aware of the fact that he couldn’t be out there strung out and he got that problem behind him — and it was apparently behind him for about a year-and-a-half until he had to come back to Kansas City, and then he got in trouble again.

JJM When Parker did arrive in New York, he was surprised to discover that Buster Smith hadn’t made his mark on the town. You wrote, “New York was full of so many good musicians, and there was so much going on, that it was easy to get passed over.” Did Smith’s relative lack of success alter Parker’s plans for his time in NY?

SC Well, it altered his plans, yes, because he thought he was going to get into Smith’s band since Smith told him before he left Kansas City that he would start a band and put Charlie on the bandstand with him. So Charlie Parker arrived in New York assuming that was going to happen, but Buster Smith wasn’t gigging. He still had a lot of respect among Count Basie and the Kansas City musicians in New York, but Basie had a had full band that was working very well together and making records, so the possibilities for Buster Smith were limited primarily to arranging and composing some tunes for the band. So Charlie Parker was there with his mentor, but his mentor wasn’t gigging, which meant he wasn’t either. But, he was in New York and determined to be accepted in New York — just as determined as he was to be accepted in Kansas City.

JJM But he wasn’t really accepted by the musicians of New York, and there was a lot of criticism about his playing. Did this lead to some self-doubt?

SC Yes, it left him with some self-doubt. Biddy Fleet points out that when Charlie Parker first started playing in New York, people didn’t like the way he played, and that basically they didn’t like him because he had a different kind of tone, and his phrasing was different. Many of the journeymen New York musicians told him he should play the saxophone more like it was being played in New York City and not try to come in with this strange kind of Kansas City approach that hadn’t yet made a place for itself in New York. They basically thought it was worthless.

But Biddy Fleet was very important to Charlie Parker because they both worked on these new harmonies. They both listened to European concert music. They both understood that there was something else that was possible in music than what guys were playing at that time, and so Biddy Fleet would tell him to ignore these people and just keep playing. He told Charlie that if he wanted to satisfy the public, he would never play the horn. So Biddy Fleet understood at the end of the 1930’s that there was a line between serious playing and entertainment, which was a thin line and could sometimes be straddled by players like Duke Ellington. There was a way you could play artistically and satisfy the public, but that was something that one had to figure out how to do, and the Kansas City musicians, as personified by Count Basie and his band, had figured that out. That was what Charlie Parker was challenged to do.

JJM Your book concludes with his need to return to Kansas City because his father was murdered, and I am assuming your next volume will pick up from there. In addition to the resources you used for this first volume, who are some of the resources we will see in the second volume?

SC Yes, you will see some of the same people, but I also got a lot of information from other people who were around him at that time — people like Max Roach and his second wife Doris Parker, who gave me a fuller picture of Charlie Parker as he became who he was. They had some very telling things to say about him, things that are beyond what we normally hear about Charlie Parker.

JJM Well, fans of Parker will be excited to read that…

SC Thanks.

JJM How has Charlie Parker’s influence on jazz music changed, if at all, since the time you began writing this book in the 1980’s to the present day?

SC Well, the only thing that has changed about his impact is that more people today may feel that they can avoid it with an academic approach that doesn’t have the kind of vitality that Charlie Parker’s real playing had. So you hear guys playing a lot of patterns and a lot of scales and a lot of simplistic or pretentiously complex foundations, and they don’t necessarily get to what Charlie Parker got to, which was a way to keep the absolute vitality of the blues and swing at the center of his aesthetic. So his style always carries the blues and always swings in a way that today many musicians think they can avoid because they are academically trained. That’s an unfortunate thought, but I don’t think it’s going to work for long. Anybody who thinks that will work should hear Charles McPherson when they get a chance to hear him, and on the other side they should listen to Wynton Marsalis on YouTube playing his Abyssinian Mass. There is some trumpet playing on there — the way he pivots from swing and from the blues — that should let people know that it is still the undeniable demand for vitality in jazz.

JJM Are you still actively involved in the Jazz at Lincoln Center program?

SC Now and then, but not all the time, because I have been busy doing other things.

JJM Given how busy you are, are you able to spend as much time writing about jazz as you would like?

SC For now, yes. In my book Considering Genius I was actually able to lay out what I was seeing over a period of 30 years — a period of talking to the musicians, seeing them in in nightclubs and concerts and festivals, and assessing what they did. So that is part of it. The Charlie Parker story is another part of it because it allows me to stand up to the greatest challenge for any biographer, which David S. Reynolds and I were just talking about. He wrote the great book Walt Whitman’s America, and he also wrote about Harriet Beecher Stowe and John Brown. While we were talking we agreed that the fundamental challenge to a biographer is to make the data come alive, and to make it possible for you or any other reader to believe what the truth actually is — not just part of the truth, and not to exaggerate it. So making the data come alive for the reader was what I was trying to do in Kansas City Lightning, and that’s what I’ll be trying to do in the next volume of the Charlie Parker story.

JJM Was there a jazz biography you read as a young man that was a favorite of yours at the time?

SC I don’t recall any, although I liked Ross Russell’s book on Parker when I read it, but the more I developed and the more I came to know, the more difficulty I had taking it completely seriously. While there’s a lot of stuff in there that’s true, there are too many urban legends in there that I’ll clarify in the next book.

.

______

.

“You could look at Bird’s life and see just how much his music was connected to the way he lived…You just stood there with your mouth open and listened to him discuss books with somebody or philosophy or religion or science, things like that. Thorough. A little while later, you might see him over in a corner somewhere drinking wine out of a paper sack with some juicehead. Now that’s what you hear when you listen to him play: he can reach the most intellectual and difficult levels of music, then he can turn around — now watch this — and play the most lowdown, funky blues you ever want to hear. That’s a long road for somebody else, from that high intelligence all the way over to those blues, but for Charlie Parker, it wasn’t half a block; it was right next door.”

– Earl Coleman

.

_____

.

Critical Acclaim for Kansas City Lightning

“A tour de force that is the print equivalent of a long, bravura jazz performance. . . Crouch has given us a bone-deep understanding of Parker’s music and the world that produced it. In his pages, Bird still lives.”

— Washington Post

.

“It is from Mr. Crouch, a novelist as well as a critic and essayist, that we come to see Charlie Parker in the context of his time and place in America. . . One comes away from Mr. Crouch’s book wanting more.”

— Wall Street Journal

.

“Kansas City Lightning succeeds as few biographies of jazz musicians have. . . This book is a magnificent achievement; I could hardly put it down.”

— Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

.

“This is a memorable book. . . Stanley Crouch takes us deep into places most of us can only imagine—including into the heart of the mysterious split-second alchemy that takes place nightly on the bandstand.”

— Geoffrey C. Ward

.

“A book about a jazz hero written in a heroic style. . . a bebop Beowulf.”

— New York Times

.

“[Crouch] crafts lush scenes and crackling music writing. . . Jazz fans will want to read this book. . . This is a thorough and entertaining account of one of the greatest rises—and the prelude to one of the greatest falls—in jazz history.”

— NPR.org

.

“[A] riveting, long-awaited book . . . Here is Bird making his watershed discoveries before he fired his own lightning bolts.”

— Gary Giddins

.

“A portrait of the young Charlie Parker with a degree of vivid detail never before approached. . . [Kansas City Lightning is] a deft, virtuosic panorama of early jazz. . . This is a mind-opening, and mind-filling, book.”

— Tom Piazza

.

.

_____

.

About Stanley Crouch

.

Stanley Crouch has been writing about jazz music and the American experience for more than forty years. He has twice been nominated for the National Book Critics Circle Award, for his essay collections Notes of a Hanging Judge and The All-American Skin Game. His other books include Always in Pursuit, The Artificial White Man, and the acclaimed novel Don’t the Moon Look Lonesome. Since 1987 he has served on and off as the artistic consultant for jazz programming at Lincoln Center and is a founder of the jazz department known as Jazz at Lincoln Center. The president of the Louis Armstrong Educational Foundation, he is a recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship, a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and a regular columnist for the New York Daily News.

.

[Mr. Crouch died on September 16, 2020]

.

____

.

Other Jerry Jazz Musician interviews with Stanley Crouch

.

Stanley Crouch, author of Considering Genius: Writings on Jazz

The Ralph Ellison Project: Stanley Crouch discusses Invisible Man author Ralph Ellison

.

*

.

You may also enjoy reading our interview with Brian Priestley, author of Chasin’ the Bird: The Life and Legacy of Charlie Parker

.

.

___

.

Jerry Jazz Musician…human produced (and AI-free) since 1999

.

.

.

Bird Lives