_____

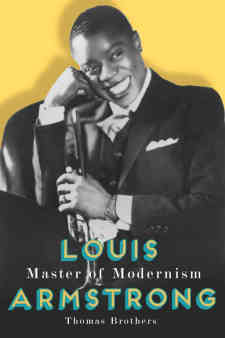

On the heels of terrific books on Bud Powell, Charles Mingus, Charlie Parker and Duke Ellington comes Louis Armstrong, Master of Modernism, author and Duke University Music Professor Thomas Brothers’ follow-up to his revered Louis Armstrong’s New Orleans.

In the book’s introduction, Brothers reports that his book picks up where Louis Armstrong’s New Orleans left off, with Armstrong’s 1922 Chicago arrival, and ends ten years later. He writes, “My main thesis is that the success of this nimble-minded musician depended on his ability to skillfully negotiate the musical and social legacies of slavery. Indeed, his career can be understood as a response to these interlocking trajectories.”

I have just begun reading it and have been taken in by “Welcome to Chicago,” the book’s first chapter that tells the story of what Armstrong would have seen as he entered Lincoln Gardens for the first time in August, 1922; for example, the racially inflected floor show whose “centerpiece of the presentation is a row of light-skinned dancing girls;” dancing couples in an environment where “correct dancing is insisted upon” (to keep immorality charges at bay); and the local white musicians — “alligators” — described as “the little white boys…motivated to learn the music and cash in.”

I had the privilege of interviewing Thomas Brothers following the publication of Louis Armstrong’s New Orleans, and he has accepted my invitation for an interview about his new book. It is my hope to publish the interview in the middle of April.

Meanwhile, I expect to be writing now and then about the book as I read through it. At the outset of this journey I have been reminded that Brothers is, as Gerald Early — one of his generation’s most respected cultural historians — wrote, “Armstrong’s finest interpreter and chronicler.”

What follows is an excerpt from the book’s introduction in which Brothers describes Armstrong’s “twin accomplishments” that made him “the greatest master of melody in the African-American tradition since Scott Joplin, the central figure in virtually the entire tradition of jazz solo playing and singing, and arguably the most important American musician of the twentieth century.” After reading this excerpt, I encourage you to go out and get the book!

The following excerpt is from Louis Armstrong: Master of Modernism, by Thomas Brothers

__________

When Armstrong arrived in Chicago in August 1922…[Joe “King”] Oliver had sent for him because he was suffering from gum disease that made it increasingly difficult for him to play his horn. He needed the support of a second cornetist, and Armstrong was not even the first player he thought of. His assignment was to play second to Oliver’s lead, which he did for almost two years. Oliver kept his maturing apprentice out of the spotlight and extended the mentoring he had begun in the mid-1910s. Among other things, he taught Armstrong how to design a memorable solo; the impact of that instruction can be clearly heard in Armstrong’s earliest recorded solo, from Chimes Blues in 1923. There also must have been lessons about the texture of collective improvisation, and perhaps composition as well. King Oliver’s recordings with Armstrong during 1923 and 1924, a treasure comprising some 30 different sides, make this phase of his career a true delight.

An important part of Armstrong’s maturation in Chicago was the enthusiastic patronage of other African Americans who had recently moved from the Deep South and were eager to discover a new cultural identity, one that incorporated the vernacular principles they cherished, yet was also forward-looking and competitive with white culture. The urban sophistication of Chicago played out musically in places like the Vendome Theater, where Armstrong first made his mark. The spotlight there was normally on operatic overtures and symphonic arrangements. Armstrong was able to match that kind of sophistication while making music that “relates to us,” as one African American observer put it. He did not stand up and shout, “I’m black and I’m proud,” but his music said so in no uncertain terms.

Without Armstrong’s early commercial recordings, we would have far less reason to engage with his accomplishments from this period. Nevertheless, that legacy is at best a partial and potentially misleading representation of what was happening. Not all recordings were created equally. Some were generated in the studio, on a moment’s notice, to satisfy the demand for one more side. A smaller number reflect what was going on in venues where Armstrong played regularly. We should not expect uniformly excellent results from such a varied profile. One purpose of this book is to work through the recorded legacy with an eye toward what it tells us about contexts beyond the studio. The irony is that commercial recordings were merely a sideshow for Armstrong, while for us they are the main event.

“Master of modernism and creator of his own style” is a good way to sum up Armstrong’s accomplishments from this period. The word “modern” is an easy term of abuse for the lazy historian, but the 1920s was a decade when the reach of the modern was extending in all directions. “Modernism will always rule,” wrote Dave Peyton, the most important African-American critic of music from this period, in a 1925 review of a Chicago battle of bands that was won by Sam Cooke’s orchestra. Modernism meant progress, the articulation of fresh forms, sophistication, something of consequence. It meant inventions of daring and speed, the Chrysler Building in New York City, talking movies, flappers, jazz, consumerism, and distance from Victorian conventions. The degree to which modernism in the black community took white accomplishment as a standard depended on how one was positioned socially and how one imagined future progress for the race. The astonishing thing about Armstrong is that he invented not one but two modern art forms, one after the other, both of them immensely successful and influential, and that he did this with vigorous commitment to means of expression derived from the black vernacular he had grown up with.

Armstrong’s first modern style, created around the years 1926 – 28 and based on the fixed and variable model, was pitched primarily to the black community. These people enjoyed his entertaining singing, but they were in awe of his carefully designed trumpet solos, which helped articulate the modern identity they were looking for. They might have been satisfied with the dazzling display of his increasingly impressive chops – the big round tone, quick fingers, and high-note playing. But he was driven to create a new melodic idiom, which made him different from almost everybody else. His compositional skills led him to craft solos of enduring melodic beauty, and that is how they should be regarded.

His second modern formulation was the result of efforts to succeed in the mainstream market of white audiences. The key here was radical paraphrase of familiar popular tunes. The basic idea was nothing new: when, during the late nineteenth century and probably long before, African-American musicians spoke of “ragging the tune,” they meant creating their own stylized version of a known melody by adding all kinds of embellishments and extensions. In the early 1930s, with the assistance of the microphone, he invented a fresh approach to this old tradition, creating a song style that was part blues, part crooning, part fixed and variable model, plastic and mellow, the most modern thing around. In 1931 and 1932, Armstrong’s recordings made him the best-selling performer in the country, regardless of genre, style, color, or pedigree, and his live performances were regularly beamed across national radio networks.

Jazz a la Paul Whiteman and George Gershwin, made by whites with the assistance of musical notation, was conceived as a modern art form with distinctly American energy, “the free, frank, sometimes vulgar spirit of the bourgeoisie,” in the words of one writer, clearly referring to the white bourgeoisie. Notation allowed composers like Gershwin and arrangers working for bands like Whiteman’s to create works of formal sophistication and artistic complexity. Although this white modernism was inspired by the African-American vernacular, it was so thoroughly transformed that its origin was obscured.

Modern jazz as Armstrong presented it was something altogether different. It was just as sophisticated as white jazz, but its terms of expression could not be transmitted through musical notation. Armstrong’s music was a unique transformation and extension of the modernist who appealed both to blacks in the mid- and late 1920s and to whites in the early 1930s.

Few composers can claim to have made significant innovations in musical style; Armstrong did it twice. Like Beethoven, Stravinsky, and The Beatles, he had a remarkable ability to move through different conceptual formations and offer a musical response that, in turn, helped define his surroundings. He learned northern showbiz ways and adapted them to foundational principles he had internalized in New Orleans. “You’ll swing harder if you learn to read music,” one musician told him around 1920, and he took the advice to heart. In Chicago he studied with a German music teacher, woodshedded the “classics” with his piano-playing wife, and learned to play higher, faster, and with more precision in the scales and chords of Eurocentric music. This project was very much in step with the agenda of the typical southern African-American immigrant who was “doing something to improve himself,” as it was often phrased.

Armstrong played the naïve Negro, as whites expected him to. But a genuine historical appreciation of his accomplishment exposes a formidable intellect totally absorbed in music. We still live with the image of an untutored musician who didn’t think too much about his music, which simply poured out of him intuitively. Few white people who admired Armstrong in the 1930s were prepared to discover in him the kind of artistic discipline that we associate with Beethoven, Stravinsky, and even The Beatles. Most assumed that Armstrong was led “only by the sincere unconsciousness of his genius,” as one sympathetic writer said about the dancer Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, just as “inspiration has always come to tribal man.” We have not completely left that kind of garbage behind.

Like all great artists, Armstrong was so thoroughly immersed in his art that he thought in purely musical terms, with no need for verbal translation. His creative genius expressed itself in abstract forms, the fixed and variable model, blues archetypes, and the transformation of popular songs. Armstrong used what he learned from Eurocentric music to infuse the African-American vernacular with new intensity and possibilities. This process produced, in the mid-1920s, a style that served as the basis for jazz solos for the next decade and beyond. After that, the combination of creative drive and hustle for the rewards of the white marketplace led Armstrong to create an equally innovative modern song style. These twin accomplishments make him the greatest master of melody in the African-American tradition since Scott Joplin, the central figure in virtually the entire tradition of jazz solo playing and singing, and arguably the most important American musician of the twentieth century. For that reason they are the main focus of this book.

*

Excerpted from Louis Armstrong: Master of Modernism by Thomas Brothers

Read our interview with Thomas Brothers about his book Louis Armstrong’s New Orleans

__________

Louis Armstrong performs “Dinah”

Thomas Brothers discusses Louis Armstrong

Louie was the best: in everything … the roundest of notes, the most buoyant of spirits and a master of jazz