.

.

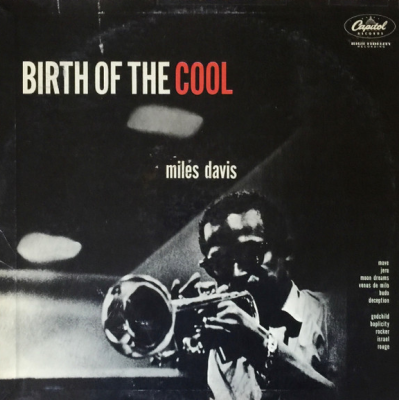

From the Jerry Jazz Musician archives, in a March, 2003 interview, David Colley, author of Blood For Dignity: The Story of the First Integrated Combat Unit in the U.S. Army, talks about the integration of the United States military, and about the courage of African American soldiers determined to achieve success before and after World War II.

.

.

…..Prior to the closing months of World War II, American military doctrine had long held that blacks were inferior fighters who fled under fire and lacked the intelligence, reliability, and courage of white fighters. That changed in early March 1945, when, for the first time, more than two thousand African-American infantrymen entered the front lines in Germany to fight alongside white soldiers in infantry and armored divisions engaged in the final battles of World War II in Europe.

…..When the 5th of K fought side by side with white soldiers and drove back the German army, they laid to rest the accepted white attitude of a century and a half that African Americans were cowardly and inferior fighters.#

…..David Colley, author of Blood For Dignity: The Story of the First Integrated Combat Unit in the U.S. Army, talks with Jerry Jazz Musician publisher Joe Maita.about the integration of the United States military, and about the courage of African American soldiers determined to achieve success before and after World War II.

.

_____

.

photo by Richard Ralston

K Company in Germany, June, 1945

“We of the United Nations must live and work together, regardless of race or nationality, creed or service, uniform or rank. Supported by our homelands, we must fight on relentlessly, side-by-side, at sea, on land, and in the air, so that we will win together a better world, secure and free for all men everywhere. Your presence here in response to the invitation of the high command to volunteer for retraining as reinforcements indicates that you and the race you represent wish to live and work together regardless of race or nationality, creed or service, uniform or rank, so that we will win together a better world, secure and free for all men everywhere at home as well as abroad.”

-Brigadeer General Benjamin O. Davis

.

_____

.

JJM You write in your book, “For 162 years, from the Revolutionary War to the last years of World War II, blacks served principally in non-combat service units, and the few who fought were relegated to segregated combat units.” What was the psychological impact of this?

DC It had a very severe psychological impact. I am working on a book right now that examines some of the reasons why men fight. I attempt to show that, throughout history, being a warrior was in some ways as close to being a deity as a man could possibly be. Being killed in combat deified many — that is the way people felt about it. I realize that is quite extreme, but there is an element of truth to this, that some men have a need to become warriors. It is a way to prove your manhood. When blacks were told by whites that they were not good enough to be warriors, it was a deep psychological blow. It essentially communicated that they were not “man enough.” Consequently, there was the feeling among blacks that they weren’t as good as whites, and a way to dispel that was to show their courage in combat. There was this need to prove themselves as men that propelled most of these men into combat.

JJM Prior to World War II, when was the last time whites and blacks fought side by side in combat?

DC During the Revolutionary War, the Continental Army did make an effort to fight without the assistance of blacks but they couldn’t afford to because they needed every able man. Also, the British were offering freedom to black slaves who fought against the Continental Army. So, while a number of officers of the Continental Army were opposed to having blacks serve, they realized that they needed the manpower. Also, there was a tradition of blacks serving as part of the militia units on the frontier, where everybody fought together for the common goal of protecting settlements against the native Americans. This was really the last time that blacks and whites served together.

JJM And then there was a period of 150 years between that and World War II.

DC Yes, there were a few blacks that served in the War of 1812, although there was no official integration of the ranks, since blacks were here and there in lower functioning positions. Then, during the Civil War, blacks tried to join but were turned away until 1863, when the army did begin organizing segregated black combat units. The film Glory told the story of one such unit from Massachusetts that fought very well in South Carolina. Because of the reputation the black combat troops of the Civil War made for themselves, following the war, Congress created a number of regiments — the 9th and the 10th Cavalry, as well as the 24th and the 25th Infantry regiments. These regiments, particularly the Calvary, became known as the Buffalo Soldiers. A number of officers actually got their training in these regiments. General Pershing, who was head of the American expeditionary forces in World War I, got his nickname “Black Jack” from serving with the 10th Calvary.

Those regiments were not sent to World War I. But, the 92nd and the 93rd Divisions — both segregated divisions — were raised during the war. It made for a very interesting comparison with white soldiers again. Blacks were denigrated and thought to be ignorant, stupid, fearful, cowardly, etc. The 92nd Division went into the trenches under American command, while most of the 93rd served with the French. Under French command, the 93rd performed very well, and was highly regarded by French commanders. In fact, many of the troops were commended for bravery and heroism. The 92nd, on the other hand, didn’t do as well, which could have been a matter of a self-fulfilling prophecy. If you expect great things of your men they will perform; if you don’t, they won’t. Many of the problems the black units had centers around the fact that they were always led by white officers, and if the officers were unhappy with their command of black troops, they didn’t have the same incentive, and didn’t always motivate the troops the same as if they were white troops.

JJM How did the northward shift of the black population and the increased education of blacks create problems for the military?

DC During World War I, approximately one in five black troops were from the North, and by World War II, it was up to the range of three out five. This migration of the early twentieth century led to jobs, a better education, and a move away from segregation and discrimination. While there was segregation in the North, it wasn’t as imbedded and virulent as it was in the South. As blacks in the North received a better education, particularly on the West Coast, they had greater expectations, and were generally less conscious of racial discrimination. These men were then sent to segregated units in the South, where this virulent racism existed. As a result, there were serious clashes between blacks and many of the whites in the Army who had grown up in the South, as well as with the white population around the military bases.

At the same time, the civil rights movement was developing steam, and during World War II, black leaders were pushing the Roosevelt administration to address their issues. Eleanor Roosevelt, who was a key spokesperson for civil rights and integration, did as much as she could to persuade her husband to integrate the army — she is said to have been responsible for integrating the Army Nurse Corps in 1945. Things were changing so rapidly in American society during the war, and these issues and more had much to do with the eventual integration of the army.

JJM There is evidence of a major disturbance at Camp Van Dorn in Mississippi in 1943 in which as many as 1,200 black troops may have been massacred. Was this immediately investigated? How did the army account for such massive loss of life?

DC Van Dorn was an explosion that could have happened anywhere. I am not sure exactly how the army accounted for it at the time. They did an investigation and filed their reports, but, to this day no one knows exactly what occurred. I talked to several people who have investigated that situation, and some who are currently investigating it. No one knows how many soldiers were said to have been killed. In 1999, there was an investigation carried out by Congressman Thompson of Mississippi, which the army was also involved in. They relied heavily on army records of 1943 and could not find any evidence of a massacre. Some people say something must have happened because there were just too many missing men whose whereabouts have never been discovered to this day.

JJM Yes, if the numbers are correct, that is a huge event to cover up. How were the next of kin of so many notified?

DC I don’t know how that took place. What I understand is that they were told that the soldier had been killed or was missing in action. Since these men came from different parts of the country, there was no organization to pull it all together and question how these deaths could have happened to so many men from the same unit.

JJM There was also evidence of an uprising of sorts at Louisiana’s Camp Claiborne in which as many as 16,000 men armed themselves and turned over buses.

DC Yes. One of the things that frequently precipitated this kind of action was that army bus drivers would drive through the military bases and pick up soldiers at various bus stops, and then refuse to pick up the blacks when they came to the black section of the base. Also, in many cases, blacks would go into town and be harassed by the military police or the townspeople, sometimes even beaten by the police. It was a frequent enough situation where blacks would finally say they had had enough and arm themselves and, on occasion, mutiny. There was an incident I wrote about in the book where a bus stopped for a group of black soldiers, but the white driver informed them that he would not pick them up because they were black. They were of course upset about this and on this occasion turned it over and started beating up the white passengers as they tried to get out of the bus.

JJM It is really interesting how many times in our history racial disturbances are caused by something that occurs on a bus. This is an example, as is Rosa Parks, or the one involving Jackie Robinson, who was discharged from the military because of his refusal to leave a bus.

DC Yes, it is interesting. These black soldiers couldn’t really find a place to go off the base without being mistreated, and they didn’t feel as though the army was taking steps to defend them — in fact the army was not taking steps to defend them. The army’s position — while it was inexcusable it was also understandable — was that they were fighting a global war and couldn’t spend a lot of time worrying about soldier’s civil rights. That was a political/civil issue that blacks and whites had to deal with in society beyond the military. The military didn’t want to be the force that integrated American society, and that was their main excuse for not doing much of anything about integrating the ranks. They felt they would be spending too much time breaking up fights and policing problems between whites and blacks, and turned a deaf ear to the situation, lived with it, and hoped it would go away.

JJM What tasks did blacks typically perform in the military during World War II?

DC As had been the case during most of the army’s history, many of them were laborers. While they were assigned to engineering outfits and were ostensibly engineers, in fact they dug ditches, built bridges and that kind of thing. Essentially they were laborers, working as stevedores, and working in transportation as truck drivers, road construction crew, unloading the trucks, etcetera. Also, a fair number of them were in Grave’s Registration units, and their job was to pick up the dead and transport them to cemeteries. Not that whites didn’t do these jobs, but for blacks, this was as far as they could go. If a white wanted to go into the infantry, armor or the Air Corps, he could do that. He could become a pilot where most blacks couldn’t. Yes, there were the black Tuskegee Airmen, but there were very few of those. So, there was very little outlet for most blacks. Essentially they were on a dead end trip in the service, stuck in the ranks as basic laborers, which didn’t have any great appeal if you couldn’t go anywhere else.

JJM Why did the United States commanders feel that integrating the military would disrupt its effectiveness in fighting the war?

DC What they were particularly concerned about was that blacks and whites would be fighting among themselves instead of fighting the enemy, and there was some grounds to believe that. For example, when the troops got to England, the blacks found that the British people didn’t have the same kind of racial prejudice as Americans, and they felt perfectly comfortable around the black soldiers. They would invite them to dinner, and the girls danced with the black men. Essentially, they were treated without prejudice. When the whites saw this, there were violent reactions. There were constant fights among blacks and whites in England, and it got so bad that in many towns, whites and blacks were not allowed into the village for entertainment on the same days. They didn’t mix them. So, this very serious racial strife that existed in America was transported to Great Britain.

What the army didn’t yet realize is that once troops got into or near combat, the racial issues started to disappear, because men had to rely on one another whether they were black or white. Once these platoons got into combat, there was virtually no racial discrimination. There was incredible harmony when these men were being shot at. I wrote in my book of one man saying there is no prejudice or racial discrimination in a fox hole because everybody is so intent on staying alive that they don’t care who the guy is next to them. They just needed somebody to help them survive.

JJM What were the circumstances leading to the Army’s decision to integrate black and white soldiers?

DC A lot of it came from increased pressure on the home front. World War II, more than any other event or period in American history, was responsible for the civil rights movement. By World War II, blacks had had enough of discrimination and segregation, and with the advent of the war and their continued relegation to second class citizenry — even while fighting allegedly for freedom while they themselves were subjugated — pressure for reform in American society was growing. More people in America were starting to realize that it was just intolerable to continue this way.

As for the war itself, until the final eleven months, the United States was not engaged in a massive land war as the Germans and Russians were, where every day along a 1,500 mile front millions of troops were fighting, incurring thousands of casualties every week. In the Pacific, there were terrible battles where several thousand men would be killed in the space of 24 hours, and there was fighting in north Africa, but it only involved several divisions. In Italy, the same thing was true, where five or six American divisions fought along a limited front. But in France, there were as many as 60 or 70 American divisions — approximately a million-and-a-half men — pushing along a very wide front. These men were fighting hundreds of thousands of German soldiers, and suddenly there were thousands of American casualties every day and every week. During the Battle of the Bulge alone, 80,000 men were casualties in the space of a month — about 19,000 of which were killed. These men, of course, had to be replaced, and by this time they were taking anybody and everybody. The Air Force had pretty much done its job, so they were taking men out of that service and putting them into the infantry. They were taking men out of anti-aircraft groups because there weren’t any German planes left to shoot down. Every available white soldier was ordered out of their old units and put into infantry units, where they were being retrained and sent to the front. Young men drafted from the United States — even those with a doctorate degree — were being put into the front line because they needed infantrymen so badly.

At this time, there were a couple hundred thousand blacks sitting behind the lines, and General Charles Lee felt that they could make a contribution. Lee was very forward thinking, in some ways, but he was also very traditional in other ways. He felt that blacks should be integrated into the ranks shoulder by shoulder during battle, but he was not in favor of integration behind the lines, socially. He suggested using black soldiers to General Eisenhower and Eisenhower agreed. They needed troops, and as many as they could get, so the order went out to find black volunteers to serve shoulder to shoulder with white soldiers. So, it was the combination of two major factors — the pressure from the home front for integration and social justice the need for men on the front — that led to the integration of the Army.

JJM And when the call for volunteers came, enough blacks volunteered for 53 platoons, 37 of which were sent to the front in March of 1945. Why did you choose to profile the 5th of K?

DC During the writing of my previous book, The Road to Victory, I found it was very challenging to find black veterans. While I was able to find them here and there, it was difficult to find the specific men who served in the platoons. There weren’t that many of them to start with, and I learned that a lot of them came home from the war and just kind of disappeared. They didn’t join any organizations the way whites did. They didn’t become members of the Veterans of Foreign Wars or the American Legion, for example, and many of them were not happy with their army experience so they didn’t care to talk about it. While it was possible to find one guy who served in a black platoon in the 9th Division, and maybe another or two who served in the 12th Army Division, putting together a coherent story of one platoon is very difficult.

When I found six or seven men who actually served in the 5th Platoon of K Company, 394th Regiment, I began putting together a complete story of their experiences, from the moment they went into training in France to the day the war ended to the day they were shipped home. I was able to interview them at length, during which time new information, stories and insight was gathered. After two years of this I had enough of a story to tell. And that is the way I wanted to present it, as a full story about one platoon and what they experienced. These men actually saw some pretty heavy combat, so it made for a great story, not only for how they engaged the Germans, but also for how they dealt with themselves and whites at the same time.

JJM What was the primary reason for this particular group to volunteer for the infantry?

DC To prove themselves. They wanted to show the white men that they were every bit as good as they were. Certainly, some joined because they were bored doing the work behind the lines, but predominantly they wanted to prove themselves — not only as blacks, but as men. They were very much aware of the fact that the reputation of blacks in general, and black men in particular, was on the line when they went into combat. It was really a matter of their saying, “I am as good as you are and I am going to show you.” And they did.

JJM Were they typically welcomed by the whites to their assigned units?

DC Generally speaking they were. Certainly the 5th of K welcomed them because they were getting attacked from all sides and were in dire straits. The 106th Division, which was reconstituted after being battered in the Battle of the Bulge, did not welcome them, so they broke up the black platoons that were supposed to wind up with the 106th and they sent them to other divisions. While some of the whites in the companies where the black platoons were assigned were not happy about it, once the men were in combat, no one really gave much of a thought to whether somebody was black. Art Holmes, one of the men in the platoon I write about, told me he was with a white man who was quite unhappy to share a fox hole with him. But after a night of being shelled and shot at, they were associating with each other very well. Generally speaking they were well received because they were reinforcements, and anybody who was in combat knew they were in need of reinforcements. They didn’t care what color they were, it was an advantage for them because they had extra troops.

JJM Why was Richard Ralston chosen as commander?

DC The army needed a white lieutenant — the platoon leader — and a white sergeant to run these black platoons. One of the 99th Division’s orders was that the company platoon leader had to have had combat experience, because they needed to train the black soldiers in the best combat techniques available. So, they selected the best they could find, which was Ralston. Ralston was told to go take over this platoon, and he was surprised to find out that he was taking over a black platoon. He rose to the occasion. He was highly trained and motivated. One of the interesting things about Ralston is that, given the circumstances of his command, his men could have just despised him, but they didn’t. They respected him very highly, which is quite revealing about Ralston and his relationship with the platoon. There wasn’t anybody I spoke to who felt he wasn’t up to par. They felt that he was one of the best officers they could have found. While he was a task master, he wasn’t so difficult that the guys didn’t like him. And because he wasn’t prejudiced, the soldiers respected and liked him, which is unusual in a young officer. He did a good job — a very good job — and the men respected him for it.

JJM What sort of psychological operations were employed by the Germans for their own people around the issue of blacks in the U.S. Army?

DC According to the black veterans I spoke to, there were two types of leaflets dropped by the Germans on to the American lines. One of them was addressed to the black troops themselves, pointing out that since they were considered an inferior race by the Americans, it didn’t make sense that they would risk their lives fighting with them. The other leaflets they distributed were addressed to the German population, and these communicated that the blacks were violent, vicious, black Africans or black Caribbeans who practiced voodoo, and to be very careful of them. They claimed that they were criminals who avoided execution by going into the army. In other words, they felt the German population needed to be wary of the black soldiers. One black soldier I talked to about this said he didn’t care if it scared the Germans. If it caused them to run, it was great, but if it made the Germans fight harder, that was another matter.

Some of the Germans had a deep-seated fear of blacks. For one, they had never seen them and thus were fearful of them. They were fearful in part because during World War I, the French Army used colonial troops from Senegal, who had a very fierce reputation. They were known to go into German trenches with their knives and butcher the Germans who were left behind. As a result, blacks did have something of a fierce reputation. Also, something that some of the black soldiers told me was that fighting was a way to express their frustrations and anger, which they took out on the German troops. In battle, very angry men who have a need to prove themselves have a tendency to fight well.

JJM It wasn’t only the Germans who had fear of the black soldiers. The U.S. Army must have also had some fear because you report there was evidence of black troops actually being disarmed at the front.

DC Yes, a number of the guys I spoke to talk about white officers being concerned, particularly officers from the South, who felt that if they trained the blacks to fight, at war’s end they would go home and fight the whites in America. So, there was this concern that blacks would eventually turn on the whites at home. Also, there was concern that antagonism among the troops would lead to fights between blacks and whites. On a number of occasions, blacks armed themselves and went after whites.

JJM How was the news of the military being integrated greeted by Americans?

DC Most people on the home front were unaware of the military’s integration. One of the complaints the black soldiers voiced was that no one in America was aware that there was any integration in the front lines, and they quoted a Mississippi senator who said at the time that the only thing blacks are good for was unloading ships and acting as laborers. The fact that few people in America knew of their role as combatants was very frustrating to them. While there were many articles in the black press about the black platoons — and some even in the military magazine Stars and Stripes –– there was not a great deal of publicity on the home front. To this day people are surprised. While working on this book, when I mentioned to people about the military’s integration during the war, it was common to draw complete blanks because they had no idea of the efforts of the blacks in combat roles. Basically, I think the American people were unaware, for the most part, of the black platoons and the black experiment, and to this day they remain unaware of their participation in World War II.

JJM There was a post war study that took place regarding the integration of the military and the performance of the black troops. Were the results of this study released immediately to the public?

DC No, not immediately. I am trying to find out whether that was the first survey the army ever did regarding performance of black troops, but I haven’t been able to pin that down. The report was conducted in June of 1945, and it proved beyond a shadow of a doubt that the black soldiers performed extremely well. I talked to an officer who served in a unit next to K Company who said that the blacks were better soldiers than the whites. He believed that this had much to do with the fact that they were volunteers who looked at this as an opportunity to prove their courage to fellow soldiers. There was a post-war study conducted by the army that found that a lot of soldiers, particularly those who were wounded or killed, had not fired their rifles, which indicated that they kept their heads down and didn’t do much shooting. While that is a flawed study, in contrast to that, an accepted finding is that black soldiers were said to go into towns and open up with everything they had — they wouldn’t stop shooting. This study was probably the first time that blacks were studied as infantrymen and shown to have more than proven themselves. The report was suppressed for awhile, and I am not certain of when it was finally released, but it was used as background material for when the army studied the ramifications and the possibilities of integration in 1945 – 1948. There were two commissions that studied the possibility of integrating the army. Both referred to the performance of the 5th Platoons, pointing out that not only did these men prove themselves as soldiers, but that whites and blacks got along very well — in some cases they openly socialized — and that everybody was relatively happy about the circumstances.

JJM In a 1944 letter inviting blacks to volunteer for the infantry, General Charles Lee wrote, “Your comrades at the front line are anxious to share the glory of victory with you.” In fact, at the conclusion of the war, blacks didn’t get to march down Fifth Avenue to share in this glory of victory at all, did they?

DC No, they didn’t. It was extremely disappointing to the black soldiers, and it soured their military experience. Shortly after the war, most of the blacks who had served in the various infantry divisions were rounded up and sent back to either their old service units or to their new, segregated service units. It profoundly affected these men, who felt that as combat soldiers who volunteered for this duty they deserved better than this treatment. There were a number of mutinies as a result, one in France in particular. Ultimately the army promised many of these blacks that they would go back to the States with the 69th Division, but they did not. At that point everybody’s objective was to go home and get on with their lives, but the treatment of the blacks at the end of the war caused some of these men to turn their backs on the army. It was a major blow to the black men to not be considered as part of the conquering army when they came home following the war.

*

“Men, you’re the first Negro tankers to ever fight in the American Army. I would never have asked for you if you weren’t good. I have nothing but the best in my Army. I don’t care what color you are, so long as you go up there and kill those Kraut sonsabitches. Everyone has their eyes on you and is expecting great things from you. Most of all, your race is looking forward to you. Don’t let them down, don’t let me down!”

– General George S. Patton

.

_______________

.

Blood For Dignity:

The Story of the First Integrated Combat Unit in the U.S. Army

by

David Colley

.

.

*

.

.

About David Colley

JJM Who was your childhood hero?

DC I followed baseball as a boy, and it was very much a part of my life. I played baseball constantly, virtually every day during the Spring, Summer and Fall. Because of that, I would say my childhood hero was Gil Hodges, Carl Furillo or Preacher Roe among the other Brooklyn Dodger players.

The veterans coming back from World War II were also heroes of mine. They were nameless fathers of my childhood contemporaries. It is partly because of them that I became interested in writing books on the soldiers of World War II. I can’t say that I have any specific hero among those soldiers, but generally speaking the men of that generation, what we call today “the greatest generation,” were heroic figures to me.

In the early forties and late fifties, my family and I moved to France for a year or two. France was a very humbled nation at that time, very seriously affected economically and spiritually. We traveled extensively throughout Europe, and in many places I saw cities in northern France and Germany that were literally leveled by the devastation of the war. That experience influenced me in terms of my writing. I remember that it was fascinating to come upon the remnants of war, playing with German gas mask canisters helmets, rusted weapons, and things like that. I became very much involved in it.

.

.

This interview took place on March 30, 2003

.

*

.

If you enjoyed this interview, you may want to read our interview with Jackie Robinson biographer Scott Simon.

.

.

#Text from the publisher

.

photos from the book used by permission of the author

.

.

.