.

.

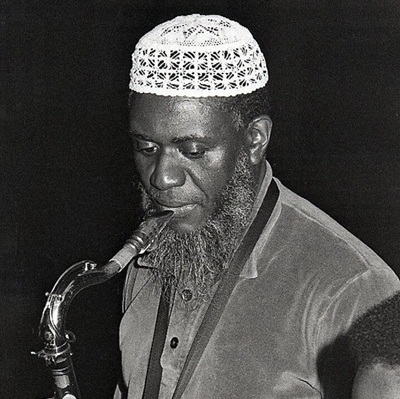

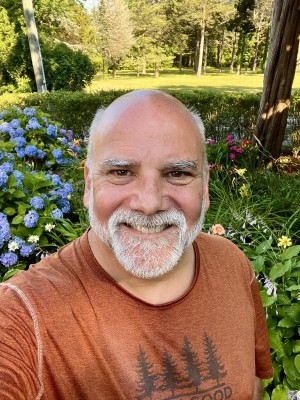

Sascha Feinstein, author of Writing Jazz: Conversations with Critics and Biographers [SUNY Press]

.

.

___

.

.

…..As an educator, scholar, poet, writer, and editor, Sascha Feinstein has devoted his life to championing jazz music. For nearly 30 years, his journal Brilliant Corners: A Journal of Jazz and Literature has demonstrated the relevance of linking the history and culture of jazz music to the very story of America, and has effectively done so by publishing interviews with – and poems and short fiction by – influential writers who share this vision. The list of some of those who’ve appeared in its pages include names familiar to many readers of Jerry Jazz Musician – Whitney Balliett, Amiri Baraka, Hayden Carruth, Wanda Coleman, Billy Collins, Jayne Cortez, Stephen Dunn, Gary Giddins, Yusef Komunyakaa, Philip Levine, Clarence Major, William Matthews, Colleen McElroy, Al Young, and Paul Zimmer.

…..Select interviews from Brilliant Corners were compiled in the 2007 book Ask Me Now, which featured Feinstein-hosted discussions from the first ten years of the journal. His new anthology, Writing Jazz: Conversations with Critics and Biographers, focuses on his entertaining, conversational interviews with 14 distinguished writers united by their careers as authors of jazz biography, criticism, liner notes and memoirs. All possess an indisputable passion for jazz, and have advocated for it through impressive bodies of work that illuminate the music, its practitioners, and its role in helping shape American culture, and its history.

…..“The fact that you can have so many really crucial writers influenced by this particular form of music speaks enormously to the impact of jazz on American culture,” Feinstein told me during the interview. Indeed, this book displays ample evidence of that.

…..In 2000, Sascha was one of my very first interview subjects – and while the discussion within this June 9, 2025 interview covers distinctly new territory – at the heart of it is his commitment to the advocacy of jazz. Writing Jazz is an impressive and determined effort, one that contributes mightily to the deepening of our understanding for the music’s past impact, and fans optimism for more.

Joe Maita

Editor/Publisher

.

.

___

.

.

The first interview I ever conducted with a writer took place in 1985, when I was a nervous undergraduate with a cheap tape recorder. My honors thesis focused largely on the poet Michael Harper, and I managed to obtain funds to bring him to campus for a reading. As a reward, I was allotted about half an hour with him in the privacy of my mentor’s office. I didn’t get to ask many questions; anyone who knew Michael knows he commanded any room he walked into. But at one point I noted that much of his poetry demanded a knowledge of jazz, and I asked if he worried about his work not being understood because of national ignorance. He replied:

Well, yes and no. The yes part of it is that every poet would like to be understood, and I don’t think that many of my poems can be understood without a little work. I don’t set out as a modus operandi to confuse my readers, but at the same time jazz music is so indigenous to American culture that even if you have a predilection not to like it, you have to really be informed about it if you want to be informed about American culture. And so I have a bias.

It seemed to me then, and much more so now, that such a bias should not only be encouraged but celebrated, and I hope these varied conversations do exactly that.

-Sascha Feinstein, from the introduction to Writing Jazz: Conversations with Critics and Biographers

.

.

Listen to the 1957 recording of Art Pepper performing his composition “Straight Life,” with Red Garland (piano); Paul Chambers (bass); and Philly Joe Jones (drums). Pepper’s autobiography, also titled Straight Life, is acknowledged to be one of the finest jazz books published. One of the interviews from Sascha Feinstein’s Writing Jazz is with Pepper’s wife Laurie, who wrote the book with Art. [Universal Music Group]

.

___

. .

JJM It’s been 25 years since our email interview, and in that time you have hosted so many interviews with so many prominent writers and advocates of jazz music, many of which are now compiled in your new book, Writing Jazz: Conversations with Critics and Biographers. I want to congratulate you on that, Sascha.

SF Thank you.

JJM Do you get interviewed often

SF From time to time and in a variety of ways. Sometimes for online blogs, and sometimes for journals, and on the radio as well.

JJM Have you been interviewed about this book?

SF [Jazz writer and NEA Jazz Master] Willard Jenkins interviewed me for his blog [openskyjazz.com]. A journalist from Sirius FM wants to do an interview with me as well.

JJM Your book is a very nice compilation of interviews with writers who talk with you primarily about their own experiences writing about jazz music. The oldest interview is about 20 years ago, correct?

SF Yes, the one with the [former New Yorker] critic Whitney Balliett.

JJM You have interviewed so many people over the years. How did you choose the interviews to include in this book?

SF All of these interviews were first published in Brilliant Corners: A Journal of Jazz & Literature, which I founded in 1996 and still edit. The first 10 years of interviews were published in a book called Ask Me Now, and I thought it would be easy to put out another interview collection of the next 10 years, but it was not. Publishers were no longer interested in highlighting primary sourced material, as astounding as that may sound, and it certainly was disappointing. So, it took me a long time to gather up a collection that could be attractive for a publisher, and the way I did it was to unite it by the type of writing that was discussed. For the journal, I interview poets, fiction writers, and at times musicians on jazz, but by exclusively compiling the conversations with critics and biographers, it created a more unified anthology, so that’s how I culled the interviews to include in this particular book.

Ask Me Now [Indiana University Press; 2007]

.

The Summer, 2025 edition of Brilliant Corners includes work by the likes of Billy Collins, Jamey Gallagher, Aaron Gilbreath, and Linda Susan Jackson

JJM In many of your interviews, writers talk about jazz, of course, but also its important role in helping us understand the history of America. I assume that’s something that you also share?

SF Yes. In my introduction I quote the poet Michael Harper – the first person I ever interviewed – as saying that you have to be really informed about jazz if you want to be informed about American culture, and I think that’s 100% true, and it’s something that I continue to actively promote in so much of what I do.

JJM How does that show up within Brilliant Corners?

SF Brilliant Corners remains, I believe, the only [printed] publication that focuses on jazz-related literature – it publishes poetry, fiction and non-fiction – and those crossovers have interested me since I was a teenager. The fact that you can have so many really crucial writers influenced by this particular form of music speaks enormously to the impact of jazz on American culture.

When I began teaching at Lycoming College in 1995, I was asked to resuscitate their defunct generic journal, but I declined. However, I was convincing in arguing for a unique journal that focused on jazz-related literature. This would allow me to publish Pulitzer Prize winners, National Book Award winners, and all kinds of heavy hitters who would not necessarily agree to have their work in a generic literary journal but who believe passionately in jazz and would be eager to be featured in it. And the very fact that that has been true for almost 30 years lets you know the importance jazz holds for so many people in the arts.

Now, do jazz enthusiasts yearn for a wider audience? You’d better believe it. And many of the people interviewed in Writing Jazz understand that we have to get the word out as best as we can. Willard Jenkins works so hard with the DC Jazz Festival and in other venues like radio to try and gather an audience. [Writer] John Edward Hasse talks about reaching listeners at an early age. You hear this again and again, that jazz needs a greater audience – and I believe that’s true, but it seems that every couple of weeks somebody writes about jazz being dead, and I have a real problem with that.

JJM Well, as we know it’s not dead at all, but attracting a younger and larger audience for the music has been a challenge since the 1950s, and we could go on for hours talking about the reasons for that.

SF Agreed.

JJM How do you decide on who you want to interview?

Kansas City Lightning: The Rise and Times of Charlie Parker, by Stanley Crouch [Harper; 2013]

.

Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original, by Robin D.G. Kelley [Free Press; 2009]

.

Clawing at the Limits of Cool, by Farah Jasmine Griffin and Salim Washington [Thomas Dunne; 2008]

SF For Brilliant Corners, generally speaking, I try to mix things up. I like to have different backgrounds and different esthetic sensibilities. In the case of this collection of critics and biographers, Writing Jazz, it’s really varied. Some of those interviewed have spent their entire lives really focused as writers, while others have only published a couple of books but have been in the business in different ways. But what unites them all, personally speaking, is how much admiration I have for their achievements. For example, I don’t think you can talk about the history of jazz criticism without including Whitney Balliett and Stanley Crouch, who are part of this book. You can’t talk about jazz biographies without talking about Robin D.G. Kelley’s book on Thelonious Monk. Farah Jasmine Griffin is one of the more important voices in jazz criticism today, and Linda Dahl was groundbreaking for her work on women in jazz. Ricky Riccardi is probably the world’s greatest authority on Louis Armstrong. So, all of these people in one way or another have contributed sensationally to our knowledge of jazz and to the field of jazz literature. That’s how I chose them. In some instances, I had personal relationships with the writer, and in others we had never met prior to the interview.

JJM So, the common thread I’m hearing is that these are all advocates for the music, which is a passion you share. And oftentimes they may display their advocacy while simultaneously promoting a book, an example being Ricky Riccardi.

SF Absolutely. Advocating for the music, and also giving back. What’s true for me – and what I’m absolutely certain is true for everybody interviewed in this book – is that we can’t imagine our lives without jazz. Period. It is a major part of our identity. So, a part of our collective efforts is to give back, to acknowledge that jazz music helped give us a life, and it’s a great pleasure for me to provide a platform on which to share that gift.

JJM You mentioned earlier that you also interview musicians. Do you find that musicians talk about the culture and the history of the music as effectively as a biographer or historian like Ricky Riccardi or Gary Giddins or Robin D.G. Kelley?

SF It’s usually a different conversation because these interviews are all about the relationship between jazz and literature, so a big part of my conversation with musicians has to do with their interaction with literature. And it’s much more common for writers to turn to jazz than jazz musicians to turn to literature, but there are plenty of cases of that, so to hear a musician talking about how she or he integrated poetry into their music is different. It’s not necessarily better or worse or easier or harder to understand, it’s just a different perspective, and I like that very much. [Poet] Jayne Cortez talking about recording with her group The Firespitters is very different than [musician] Eri Yamamoto talking about what it was like to play behind Jayne. A poet talking about working with musicians is different than [composer/bandleader] Maria Schneider talking about trying to integrate poetry into her music and orchestrate behind it. But I like that call and response between the two. Writing Jazz is more cohesive in terms of the focus on a particular type of writing, but I do miss the greater jam session of Ask Me Now, which involves a wider mix of people talking about exchanges between the two art forms.

JJM Is there a stereotype about jazz musicians from the 40s and 50s not being literary?

SF 100% true. First of all, musicians are justified in saying that they want the music to speak for itself. Second, you have legendary figures like Thelonious Monk, for example, who was known not to say very much, which helped play into the stereotype. But I do believe that has changed substantially. The great bassist Bill Crow has written short stories and a two books of non-fiction, and is incredibly articulate and funny and well-paced in his rhetoric. But I understand why that stigma held for a while.

JJM Cecil Taylor was famous for reciting his poetry during his performances, and [Charlie Parker biographer] Stanley Crouch told me that Charlie Parker was very well read. Lester Young was very well read, from what I understand. So, one can’t help but think that this stereotype was a racist trope – they’re Black, they’re musicians, the culture is filled with drugs, so they must not read.

SF Race plays into so many conversations, and this is one of them. The racism that has taken place – and takes place – in this country certainly filters into discussions about jazz and what constitutes being smart. The fact of the matter is that it’s just wrong; it’s a grotesque way of viewing the world. And as you say, there are so many musicians who were, in fact, very well read. But being very well read doesn’t mean that you’re necessarily well educated (in an academic sense), and you can be an intellectual without being very well read. It’s a deeply complex issue that you’ve raised here, and it can’t be answered simplistically.

JJM Do you still get excited when you land an interview with someone?

SF I do, and I work diligently to prepare for them. If I’m good at anything, I’m good at doing the legwork, and so I’m pleased when the person I’m interviewing is a little surprised, perhaps, that I know something about their lives that they didn’t think I would know. I’m delighted by interesting stories, and I’m pleased when a question leads to a memorable, fascinating response. It’s largely a great pleasure.

JJM What is your general process for preparing for an interview?

SF If it’s an author, I will try to read everything that person has written, and I also try to read interviews with that person. I do have specific questions that I’ve written down, but I don’t go at them, necessarily, in a strict chronological order. I usually start by asking about their foundational years growing up, and then introduce questions that I hope will trigger passionate conversations. But I also try to be very open with where this person wants to go. In other words, if the conversation leads to an interesting direction that I didn’t expect at all, I’m going to swing with that, which is why it is important to have read everything possible so that one can move in those directions.

photographer unknown

Whitney Balliett

JJM It shows up in your interviews, and I am impressed with how conversational they are.

SF Thank you. You never know where interviews are going to go and what will happen during them. My interview in the book with Whitney Balliett is an example. We were friendly and had met a number of times prior to that particular interview. Our conversations had been easy – we liked each other and so on and so forth. We met at his home on the Upper East Side, but once I started the tape recorder I couldn’t get him to talk at length. A whole bunch of one-word answers. (Ironically, when he spoke to me about his own experience during difficult interviews, he complained about people who didn’t want to talk!) But Whitney was not a talker. In fact, if you want a good laugh, see if you can find some radio interviews with him, because the dead air – which is, of course, a nightmare for any radio show host – will make you cringe (and laugh). So, that was a very difficult interview for me, and I didn’t expect it to be. The interview may not have the depth of others in the book but it is an important one because there aren’t many with him.

And then there are others where I anticipated sensitivity and pushback but that ended up being excellent exchanges. For example, when I interviewed Stanley Crouch, I drove into Manhattan to meet him but he kept me waiting for over an hour and arrived with his dirty laundry! It made me feel as though he didn’t think much of me, or that I had to prove myself to him. But he warmed up quickly enough, and we ended up having a somewhat hard-edged and at times explosive conversation. I ultimately felt very pleased with it. So, you never know what will happen because you are dealing with complex people.

JJM I’ve conducted several interviews where I ask someone a question and they respond with a ten-minute monologue. Stanley was certainly capable of that, but he was at least a fascinating subject. I call these monologues “college professor” interviews, and I find them to be a challenge because they can come across as a lecture, which makes it difficult for a personality to emerge. I’ve also encountered interview subjects who don’t complete their thoughts, or whose speaking style involves a lot of “you knows” and “I means” that tend to make the editing process problematic. How do you save an interview when you encounter a challenging situation or personality?

SF It really depends on what you mean by “save.” With Whitney, I had to extract a great many of my questions and knit his shorter answers together. And then there are just times when you have to be patient. The last time I interviewed the poet Michael Harper, I started the tape recorder, and in the first hour and 47 minutes I asked exactly two questions, neither of which he answered. I was very grateful to no longer be using cassettes that had to be popped in and out. But, more important, I knew I just had to be patient: I may not be able to use these first two hours, but I’ve got other things to ask, so let’s keep going.

Regarding the “college professor” lecturer, I don’t know if I’ve ever had an experience with the type of academic response that you’re describing. I’m an academic myself so I understand the kind of staid, passionless retorts profs are capable of, but the truth is that the people I’ve interviewed who have been in academia – like Farah Jasmine Griffin or Robin Kelley – were not like that in the slightest. I feel that they were very human and honest and open.

The issue of people not finishing their sentences can be an absolute nightmare. When I talked earlier that I’ve had experiences with people who take nearly two hours to tell a story, I meant it. That can be a mighty challenge to cut and paste and make it readable. I don’t want to simply transcribe exactly what has been said because a reader doesn’t want that. You want these interviews to be conversational and readable, right? So, yes, some interviews can be a real challenge to finalize.

JJM In your interview with Louis Armstrong biographer Ricky Riccardi, the two of you spoke about his fellow Armstrong scholar Thomas Brothers, whose work Ricky was a bit critical of. Drawing out honest criticism of a fellow writer in a published interview isn’t easy, nor is publicly challenging them. Is that difficult for you?

SF Generally speaking, I’m far more interested in celebrating writers than eviscerating them, but, yes, there have been writers I’ve publicly dismissed, and I guess I have been hardest on Leslie Gourse’s work. Whenever I ask a critic to comment on other critics, or if get to a point in an interview where I fear I may be touching an iron that is too hot, I will delicately broach the topic by asking if it’s okay to talk about it. Hettie Jones, for example, was the only person I interviewed who said in advance what could not be discussed – her marriage to Amiri Baraka. I understood that and was fine with it. He did come up a bit in our conversation, but I was careful not to abuse that request.

Years ago, when I was interviewing the poet Sonia Sanchez, who had been married to Etheridge Knight – which must have been an explosive marriage – I asked her if it was okay to talk about Etheridge and about his work, and she said that it would be fine, but I suspect she appreciated that I asked instead of just launching into questions about a delicate subject. There are many people who don’t want to be critical of others under any circumstances, and I can appreciate that, but I also think it’s very important to be honest. If somebody has had a major shortcoming, or if their work has promoted problematic claims, it’s worth noting. That’s important to do when you’re talking about jazz-related literature, or any kind of literature.

JJM Who are some of the people you didn’t get to interview but wish you could have?

SF August Wilson, for starters. I courted John Edgar Wideman for years, but he never responded to my messages. Ishmael Reed is another writer who has never responded to any of my overtures.

JJM August Wilson was at the top of my list for a long time, but I waited too long to reach out, but I would have loved to have interviewed him. And Baraka was another, but I honestly didn’t have the courage to do so, and there is no way I could have prepared properly for him. Not to say he would have agreed to an interview…

photo Swing333/via Wikimedia Commons

Amiri Baraka, 2013

SF I did interview him, which was first published in Brilliant Corners and was then anthologized in Ask Me Now. I went to his home in Newark, New Jersey – which was a long drive – and at first he didn’t answer my knock on the door even though I was right on time. I waited for about 25 or 30 minutes and thought, “This is a classic 1960s blow off,” you know? And then suddenly the door opens and he says, “Oh, I didn’t hear you. You like wine? Let’s go get some wine.” I ended up spending the day with him. He couldn’t have been more welcoming, and he laughed about his past. So, it turned out to be a marvelous experience.

JJM That’s something to be proud of, for sure. Since it’s been 25 years since we were last in contact with each other, let’s use that as a time frame for this question: We know about the likes of Gary Giddins and Stanley Crouch and Dan Morgenstern and Martin Williams – their work will be part of jazz scholarship for years – but who are among the most important contemporary jazz critics and biographers who have emerged in the last 25 years?

SF Well, let me first say that Ask Me Now also includes interviews with Gary Giddins and Dan Morgenstern, and I think that Writing Jazz speaks to your question. When I think of the writers I really appreciate right now and what they’re doing, it depends on the medium. For example, I don’t really know of a better jazz biography than Robin Kelley’s book on Monk, but what Ricky Riccardi has done for Louis Armstrong has been absolutely invaluable, and the latest in his trilogy might be the best of them all. But biography is a different approach to criticism than writing liner notes, and when I think of great contemporary liner notes writers I go to Bob Blumenthal and Willard Jenkins. I have great respect for a lot of people who are writing on jazz, but sometimes I have to compartmentalize, not only by what their strengths are but also what their contributions have been. Do you have particular people in mind?

Ricky Riccardi

JJM Well, Riccardi, for sure. I think he’s brilliant. He combines great scholarship with an ability to write a beautiful story. His most recent book about Armstrong’s early life was like watching a movie, and it wouldn’t surprise me if it eventually becomes one. I really loved the Henry Threadgill autobiography, which he wrote with Brent Hayes Edwards. The work Edwards did on that was impressive, and it is one of the more memorable jazz biographies I’ve read. It’s up there with the book on Art Pepper – which may be my favorite jazz biography. There are other hidden gem jazz biographies to read. Travis Atria’s book on the trumpeter Arthur Briggs and his internment in a Nazi concentration camp is a must-read…

SF Right. I thought that the stories in there were jaw dropping, even if the prose was a little workman-like for my taste.

JJM I would recommend the recent Eric Dolphy book by Jonathan Grasse. He’s an excellent writer, especially when it comes to critiquing Dolphy’ music. Another interesting book is Jazz with a Beat by Tad Richards, which tells the story about how jazz divided itself in the 40s, with half the musicians going the way of bebop, and the others going the way of Louis Jordan and what ultimately became rhythm and blues.

SF It is indeed an impressive book, and, I might add, published by Excelsior Editions/SUNY Press, which also published Writing Jazz.

JJM So, there is still some very good scholarship out there, which is impressive given the fact that many of the books published about jazz probably only sell about 60 copies.

SF I agree. Every time somebody tells me that they just bought a book of mine, I say; “Thank you. You just doubled my royalties!”

JJM Let’s talk a little about your work with Brilliant Corners. In a world where there are so many choices for disseminating information and entertainment – via the web or podcasts, for example – you continue publishing in journal form only your terrific long form interviews and jazz literature. Why is that?

SF Because I’m a Luddite [laughter]. I still believe in holding a book and the tactile warmth of that experience. I don’t download songs; I want to have the actual CD or LP so I can also read the notes and all the other information that comes with it. There’s a much greater intimacy. I spend plenty of time on the computer, but I don’t find it to be a cuddly experience. I love everything about books. What can I say? I’m old school.

JJM What is your goal as an editor when determining what gets published in Brilliant Corners?

SF That’s a great question and a difficult one to answer, because I embrace variety in literature, much the same way I embrace variety in jazz. When I receive a submission, I’m not looking for any particular thing other than having the poem or short story or essay reach me on both an emotional and intellectual level. I want to be moved. I want that kind of exchange between the heart and mind. And I’m proud to say that I have turned back submissions by incredibly prestigious people whose work didn’t move me. I’ve also published a great many people who have never been published before. So, I don’t have any agenda other than just wanting the best work that, in my opinion, I can publish. The range of poems alone will tell any casual reader that there’s no specific formula. There are so many different ways of approaching the music when writing about it, and I’m just interested in well-crafted, beautiful work.

JJM We are similar in that I’m not a stickler for anything other than I just would like to be moved emotionally and intellectually challenged. It is often very difficult to have both. Of course, publishing an online journal like Jerry Jazz Musician is different than a print journal like Brilliant Corners because other than how much energy I have to edit and how much patience and interest readers I perceive readers to have in consuming lengthy collections of jazz poetry, there aren’t any space limitations. So it provides me a little more opportunity for risk and to work with emerging writers – many of whom are coming to poetry for the first time after long careers in unrelated employment. At times I will receive a poem that isn’t very good, but I see something in the writer and in their soul and passion for the music and decide to publish it. It gets emerging writers excited, so I will mostly encourage them to keep writing in hopes that they find joy in the process of writing and that it improves to the point where they can become effective advocates for the culture of jazz. I have seen this happen time and time again.

SF That’s very generous. I don’t do that exactly. If there’s something that has a lot of promise but I have some quibbles, I’m very honest and I will express my reservations. They are free to tell me they disagree, but if they are willing to work with me it almost always plays out for the best.

JJM Who are the musicians that poets and authors write the most about?

SF It used to be Coltrane and Bird and Billie. There are fewer Bird poems now, but still plenty of ones for Coltrane. There remains a strong focus on music from the mid-1950s to mid-60s, but also more and more poems are about little-known contemporary players who poets were affected by after witnessing them in performance. The one thing that I do find is that authors who are new to jazz will often lock onto a subject they find to be incredibly enticing without realizing that it’s already been covered extensively. For example, I receive many poems about Chet Baker falling out of the window in Amsterdam. Not sure we need another one of those…

JJM Are you finding that you’re receiving more submissions about more revolutionary jazz figures like Albert Ayler, Cecil Taylor, or Ornette Coleman? Are you seeing a shift at all?

SF I’m not. I’m getting very few of those poems. But Monk remains incredibly popular, and Mingus to some degree, but the ones you just named, no, very few, and I don’t know exactly why, except that their music is not for the casual listener.

JJM In the introduction to your book, you write about how you were introduced to jazz music at an early age by your father and godfather. In our day – you are 62 and I’m 71 – buying records was expensive, and discovering music required more reading of album reviews and digging in record store bins. It was a more personal and demanding experience than today’s streaming culture, where everything is available for $11 a month and with a click of a finger. What was your process for determining what jazz music to buy?

SF A few things immediately come to mind. The first is that my father, who was not passionate about jazz, nevertheless had quite a number of jazz albums. So, I started spinning everything that I could from his collection. For example, I’d play Art Blakey Live in Birdland, which would make me want more Blakey and any of the giants associated with him. My godfather, Thorpe Feidt, was very influential because he gifted me albums and shared those he owned, which helped me enormously in terms of what to buy or how to go about buying. Eventually it became pretty clear to me that if I saw a record by Coleman Hawkins backed by a good rhythm section I would end up taking home a pretty great album. And there were particular figures, like Monk, where I just wanted to buy everything he ever recorded.

My wife once said that jazz can be a virulent addiction, and it is true that I have collected it compulsively for a long time. It did help once I started publishing about jazz, which meant I was getting promotional copies from the labels, and swelled my collection exponentially. But even early on, yes, it was expensive. You had to build a collection of great records slowly. And I learned what to purchase by who the sidemen are on albums by artists I collected, which created a great avenue into deepening my understanding of the artists, the music, and the history. Of course, the liner notes on the back of the LP and reading books on the history of jazz became very impactful. As you said earlier, Art and Laurie Pepper’s book Straight Life is one of the most extraordinary books on jazz ever written, and it made me want to know more about the music of this artist. My interview with Laurie is in Writing Jazz.

So, that’s basically how I went about it. Sometimes, of course, it was a sure win – I mean, is there a bad album with Zoot Sims and Jimmy Rowles? I don’t think so. I often say to people that there are certain artists you can almost buy “blindly” because their output is just so consistently great. But take someone like John Coltrane – who is a lot like James Joyce, in my opinion. If you read short stories from Dubliners and think it’ll prepare you for reading Finnegans Wake, you’re in trouble! Similarly, if you go from Coltrane’s Blue Train to Ascension, it is a huge leap. That takes a lot of time and some very deep, sequential listening to his career output.

JJM And when you get to those kinds of records it can be a solitary listening journey because not many friends will want to join you on that experience…

SF That’s right. I didn’t have any friends my age who were passionately drawn to jazz.

JJM I got into Impulse! through Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, which made me curious about the label’s other artists. As an example, for a time I would pick up any record on Impulse! and it opened an avenue for me to begin listening to and eventually accepting artists like Pharoah Sanders and Archie Shepp. So, for me there was a trust factor with certain labels, and I recognized which was more adventurous than another. I was also attracted to the album covers, and if the art spoke to me I would often take a chance on buying the record. Was that true for you as well?

SF 100%. I’m the son of two visual artists, so that was hugely important to me. The cliché about cover art is “Don’t judge a book by its cover,” but I always judge a book by its cover because it’s your introduction to the content. I don’t understand why so many of today’s jazz album covers are so dull, especially given all the advancements in technology for enhance the art. In contrast, look at the fabulous Thelonious Monk covers – Monk’s Music, Brilliant Corners, Underground, and on and on – that were so visually stimulating. You’d admire the cover, put the LP on the turntable, and read the album notes. That was a complete experience with the music and the culture.

JJM Do you keep up with contemporary jazz?

SF I certainly try to. I still write reviews for Jazziz, but I literally can’t keep up with the number of recordings that get released.

JJM In the 25 years since we last spoke, what are some of the things that make you proud about your professional life?

SF I am proud of Brilliant Corners and keeping a print journal alive. A central goal for any journal is to celebrate others, which I feel is very important, especially now when the world’s focus seems to be more about taking than giving. So, I’m pleased about that. I’ve written books of poems and memoirs that mean a great deal to me. The truth of the matter is that, while I’m best known as a writer, I identify myself more as a teacher. I also enjoy keeping up with some fine students after they’ve graduated and following them along on their young, wonderful lives.

JJM Why should readers buy Writing Jazz?

SF I couldn’t generalize about the readership, but all of the buyers of this book will undoubtedly have an interest in jazz to some degree or another. Beyond that, the conversations in Writing Jazz involve topics like politics of race and gender, and the interactions between art and our society that are much more global in nature than just a focus on jazz. In almost all of these interviews, I try to expose the humanity of the writer, which I feel is so important. It’s an essential component to my teaching as well. I want my students to know that there are real lives behind these texts they’re studying, that they were made from human sweat and human emotion and human thought, and not to dismiss that very organic and spiritual and soulful aspect.

.

.

___

.

.

.

Writing Jazz: Conversations with Critics and Biographers [SUNY]

by Sascha Feinstein

.

.

Critical acclaim for Writing Jazz

“If I had to choose the one book that best captures what Whitney Balliett called ‘the secret emotional center in jazz,’ it would be Writing Jazz. Sascha Feinstein’s conversations with a dazzling array of writers uncovers a lot about jazz’s ‘extraordinary little kingdoms and fiefdoms and neighborhoods,’ as Tom Piazza describes jazz’s intricate ecosystem. But the true magic of this book, the reason both seasoned jazz nerds and curious neophytes will love it, is this: through engrossing dialogue and storytelling, Writing Jazz illuminates more clearly than ever why and how jazz takes hold of its listeners and never lets them go.”

― John Gennari, author of Blowin’ Hot and Cool: Jazz and Its Critics

.

“In Writing Jazz, Sascha Feinstein’s probing helps us to know fourteen writers who are smart, thoughtful, and excellent company.”

― Gary Giddins, author of Weather Bird: Jazz at the Dawn of Its Second Century

.

.

___

.

.

About Sascha Feinstein

Sascha Feinstein’s is Professor of English at Lycoming College in Williamsport, Pennsylvania. His 12 other books include two poetry collections (Misterioso, winner of the Hayden Carruth Award, and Ajanta’s Ledge) and two memoirs (Black Pearls and Wreckage). For 17 years, he hosted Jazz Standards for NPR. In 1996, he founded Brilliant Corners: A Journal of Jazz & Literature, which he still edits. His honors include the Pennsylvania Governor’s Award for Artist of the Year.

Click here to visit his website

.

.

_____

.

.

This interview took place on June 9, 2025, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita

.

.

_____

.

.

Click here to read the 2000 Jerry Jazz Musician interview with Sascha Feinstein

.

Click here to read other interviews published on Jerry Jazz Musician

Click here to subscribe to the (free) Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter

Click here to help support the ongoing publication of Jerry Jazz Musician, and to keep it commercial-free (thank you!)

.

___

.

.

Jerry Jazz Musician…human produced (and AI-free) since 1999

.

.

.