.

.

“Great Encounters” are book excerpts that chronicle famous encounters among twentieth-century cultural icons. In this edition, Con Chapman, author of Rabbit’s Blues: The Life and Music of Johnny Hodges, writes about Hodges’ early musical training, and the first meeting he had with Sidney Bechet, the influential and legendary reed player who Hodges called “tops in my book.”

.

.

.

___

.

.

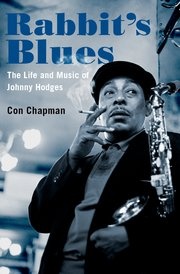

Excerpted from Chapter Two, “Young Man With a Sax,” from

Rabbit’s Blues: The Life and Music of Johnny Hodges

by

Con Chapman

(Oxford University Press)

.

.

.

___

.

.

photo William Gottlieb/Library of Congress

Johnny Hodges (foreground) and Al Sears, Aquarium, New York. November, 1946

.

.

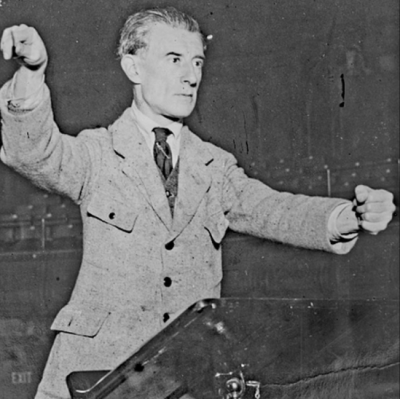

photo William Gottlieb/Library of Congress

Sidney Bechet, Freddie Moore, and Lloyd Phillips, Jimmy Ryan’s (Club), New York, N.Y., c. 1947

.

___

.

…..Johnny Hodges was first attracted to the saxophone, he said, because a particular soprano model he saw in a store window “looked so pretty.” His father refused to buy one for him, so he did what boys have historically done when thwarted by paternal parsimony; he went to his mother. He told her that if she didn’t buy the horn for him he’d get one the way “the bad fellers” did—by theft. Perhaps fearful that he meant it, she agreed even though on her husband’s pay and tips and her income as a $3.20 a day maid, the purchase represented a luxury.

…..The Hodges family was a musical one—Hodges recalled that everyone played “a little piano for enjoyment”—and his parents encouraged him “to learn how to play piano,” but he “wanted to play drums. I beat up all the pots and pans in the kitchen.” His mother persisted; “My mother used to give me piano lessons,” he recalled, “but nothing ever happened.” On this point, Hodges is too modest; he learned enough to be able to develop musical ideas on the keyboard, a skill that would serve him throughout his career. As a youth he was good enough to play “house hops”–paid admission dances in private homes to raise money for the necessities of life–usually rent, hence the other name by which these affairs were known, “rent parties.” According to Willie the Lion Smith, the profit from such an event could be substantial—the household would stock the party for as little as twelve dollars, and could sell its wares for fifty times the cost. For pianists, typical pay for such a night’s work in the Boston area was $8 (the equivalent of around $100 today), enough to attract good players; one night Hodges was relieved by Bill (not yet Count) Basie, three years his elder, who was “in town with a show.”

…..While Hodges liked to say that he was self-taught on the saxophone, he received both informal musical schooling from friends and acquaintances and some formal instruction. Hodges himself described his education thusly: “I didn’t have any tuition (used in the archaic sense of instruction) and I didn’t buy any books. A friend, Abe Strong, came back and showed me the scale just after I bought the horn, and I took it up from there by myself, for my own enjoyment, and had a lot of fun. So far as reading went, I took a lesson here and there, and then experience taught me a lot, sitting beside guys like Otto Hardwick and Barney Bigard.”

…..The lessons Hodges received were few, perhaps because he was naturally talented, perhaps because instructors cost money, perhaps because he was an impatient student. According to Rex Stewart, Hodges took lessons and “after about eight or ten sessions, the teacher asked, ‘Show me how you do this,’ and ‘How did you do that?’ So Johnny figured he knew more than the teacher and stopped.” The instructor in question may have been a Boston man named Bob Joiner, who according to one source told Hodges “you’re finished taking lessons from me . . . how about teaching me a few things?”

…..Hodges also received lessons from Jerome Don Pasquall, who taught his neighbors Harry Carney and Charlie Holmes as well. Pasquall was five years older than Hodges and received his early musical training in a boys’ band outfitted by a fraternal order, as did Carney. He played with various groups in St. Louis and in 1921 began to work with Fate Marable’s band on riverboats plying the Mississippi River, as Louis Armstrong had before him. He studied and gigged in Chicago before leaving around 1923 to study at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston. While a student there he played with local bands and in New York until June of 1927, when he graduated and left Boston permanently to join Fletcher Henderson as lead alto. This chronology would mean that Hodges began to take lessons from Pasquall when the former was perhaps as young as sixteen. Regardless of the details of his formal musical education, as a result of his limited training Hodges was not a quick study as a sight reader, and he relied on his ear and assistance from bandmates throughout his career to pick up new material.

…..Hodges benefitted from the concentration of saxophonists in his neighborhood in [Boston’s] South End, which came to be known as “Saxophonist Ghetto” because of the number of practitioners of the instrument who lived there, including Carney, Holmes and Howard Johnson, who while younger than Hodges had learned to play sax from his older brothers, Charlie and Bobby. Johnson recalled how Hodges used stealth to acquire some rudimentary instruction from him after Hodges acquired his first horn; Hodges sent another boy to invite Johnson to view his new sax, and when Johnson arrived he played a few scales on it. “That was what he wanted to know,” Johnson said.

…..There are the fundamentals, and then there is the style that a player chooses to adopt, and for that Hodges looked first to Sidney Bechet, who played frequently in Boston burlesque shows even though, as Nat Hentoff put it many years later, “Sidney is not too fond of Boston.” In the early 1920’s Burlesque impresario Jimmy Cooper staged a mixed-race show in Boston and other cities called the “Black and White Review,” whose first act was performed by “an entirely white cast” while the second featured “twenty Negroes.” Cooper promised “complete separation” of the performers by race and “complete satisfaction to the audience.” Among those in the second act was Bechet, a mixed-race Creole of color.

…..Hodges took in the show for two years running, and finally persuaded his sister Claretta, who was ten years older than him and already acquainted with Bechet, to introduce him to the great jazzman. Hodges brought his curved soprano saxophone to the theatre “wrapped up in a cloth bag” made from a sleeve of one of his mother’s coats. The two siblings went backstage to see Bechet–“I had a lot of nerve,” Hodges later recalled–“and I made myself known.”

…..“What’s that under your arm?” Bechet asked Hodges.

…..“A soprano,” Hodges replied.

…..“Can you play it?” Bechet asked.

…..“Sure,” Hodges replied, although he had reportedly owned the horn for only a few days.

…..“Well, play something,” Bechet said, and Hodges responded with “My Honey’s Lovin’ Arms.” Bechet expressed his approbation with a simple “That’s nice.”

…..On June 30, 1923, Bechet’s sound was captured for the first time on record as a member of Clarence Williams’ Blue Five on “Wild Cat Blues” and “Kansas City Man Blues.” Thanks to the technological innovation of the phonograph, Hodges became an early student of a form of musical self-instruction now well-established; learning by listening to an idol’s records. “I used to enjoy going to Johnny’s house because he had a very good record collection, and we used to borrow ideas from records and copy as much as we liked,” Harry Carney would recall. “We had the old Victrola that you wind by hand, with the horn. It gave us the feeling of being sort of big-time musicians, being able to play some of the things that were on records, for instance by Sidney Bechet, who was our idol.” Hodges and Carney were electrified by Bechet’s tone, and they wore his records out playing them over and over.

…..“Sidney Bechet is tops in my book,” Hodges would later tell British jazz writer Henry Whiston. “He schooled me a whole lot,” Hodges related, “if it hadn’t been for him, I’d probably just be playing for a hobby, not even professionally.” Hodges would initially fashion his style from what he heard on records by Bechet and Louis Armstrong. “I had taken a liking to [Bechet’s] playing, and to Louis Armstrong’s which I heard on the Clarence Williams Blue Five records, and I just put both of them together, and used a little of what I thought of new,” he told Stanley Dance. In later remarks he would credit Frankie “Tram” Trumbauer, the C-melody saxophone player who recorded seminal jazz pieces with Bix Beiderbecke, as the third leg of the stool on which his fully-developed sound sat. At some point Hodges realized the alto’s pre-eminence as “the determining voice among the saxophones as the violin is among the strings,” and “switched to alto,” then he “started playing them both.” Eventually, his schoolmate Carney convinced him to switch from the curved soprano to a longer, straight model. “[I]t was I who made Johnny buy a [straight] soprano,” Carney said. “I thought he looked kinda sharp walking along the street with an alto case in one hand and a long soprano case in the other.”

.

.

___

.

.

From Rabbit’s Blues: The Life and Music of Johnny Hodges by Con Chapman. Copyright © 2019 by Con Chapman and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.

.

.

.

.

.

One comments on “Great Encounters: When Johnny Hodges met Sidney Bechet”