Great Encounters

Book excerpts that chronicle famous encounters among twentieth-century cultural icons

*

______________

The story of W.C. Handy’s first recording session, and meeting James Reese Europe

Excerpted from

W.C. Handy: The Life and Times of the Man Who Made the Blues

by

David Robertson

_________________________

Harry Pace, even at his distance at Atlanta, always had been more innovative in marketing their firm’s songs in newer ways than Handy, and, as his career later reveals, he was interested in the possibilities of owning his own phonographic business. While on a trip for his insurance company to New York City, Pace made arrangements with Columbia records for Handy and his orchestra to make their first phonographic recordings, contracted for September, 1917. The orchestra would record Pace & Handy properties, and, with legal permissions, some other popular blues and rags the company did not own. (“The Memphis Blues” would not be among them.) But Handy’s impecuniosity almost broke the Columbia deal before a first record had been pressed.

When he told his best Memphis musicians about the up-coming session, their reactions were, bluntly summarized, W. C., we don’t think you’re good for it. Some objected because they would have to give up sure-playing local engagements for the financially uncertain trip to New York City; others were more forthright that they did not think Handy could fully pay their up-front expenses for train travel and hotel rooms. In the end, he was able to persuade only four Memphis musicians who knew him to take the risk, out of a total of twelve whom Pace had promised to record as “Handy’s Orchestra of Memphis.” Two of Handy’s perhaps most talented former sidemen, Ed Wyer on violin and William King Phillips on clarinet and saxophone, had moved to Chicago, and when Handy called upon these two for their services, they diplomatically pled Chicago union regulations as prohibiting them from playing in New York City. Handy filled out his needed number by hiring three other Chicago musicians on cello, bass, and drums who had once played for him in Memphis, and four other Chicago pick-up musicians who had not worked with Handy for needed violins and saxophones. The twelfth, a clarinetist, was apparently hired at the last moment in New York City. Financed in part by a loan which Handy previously had taken out secured by his household furnishings – and which may have occasioned another, non-comical Maggie-and-Jiggs domestic scene at 659 Janette Place – the mixed group calling themselves “Handy’s Orchestra of Memphis” barely caught an already-moving passenger train out of the Memphis station and headed toward their New York City recording session.

One who was not on this train was guitarist Charlie Patton, later known as the “King of the Delta Blues.” Patton enjoyed Handy’s music, and a mutual friend earlier had praised Patton to Handy with some qualifications – “He can play what he knows to play.” Handy generously had invited Patton to attend an engagement with his orchestra at Beulah, Mississippi, a cross-roads town outside of Rosedale. Patton presumably got in free. But Handy’s band were strictly score-reading musicians, and Patton soon had realized that he “couldn’t play no-how ’cause he couldn’t read that music.” He gave up any ambition to play with Handy’s bands.

Despite being a skillful score reader, Handy always remembered his intimidated entrance into the “little airtight studios” at Columbia to make his first, mass-produced recording. He and the other musicians were instructed for reasons of acoustics to sit down to play their instruments on wooden stools of various heights throughout the studio. (There was no vocalist for these sessions.) Recording horns dangling from the ceiling above the performers’ heads were connected via mysterious-looking acoustical tubing to the studio’s central recording machinery. Throughout four days, September 21 through the 22nd, and again on September 24 and the 25th, this group who had not previously rehearsed with one another recorded fifteen songs while being led by Handy on cornet or trumpet. Ten eventually were released by Columbia early the next year, two to a disc.

As expected, the performances by what were essentially a group of musical strangers were a little stiff; Handy later commented that these recordings of 1917 were “not up to scratch.” These were not songs played as he and his best Memphis orchestras had performed them about the Pattona, or atop the Alaskan Roof Garden, or Gordon Hall. But the group does a credible performance of a Pace & Handy owned property, “Snakey Blues,” complete with tapped wood blocks, that along with trombonist Sylvester Bernard and xylophonist Jasper Taylor, almost swings; one of the clarinetists tries hard, but not quite succeeds, in taking a blues break. On one of the two Handy-composed songs subsequently released by Columbia, the “Ole Miss Rag,” the playing is much more sedate; it is as if Handy, always what musicians called a “score eagle,” had insisted that there would be no deviation from his score. Things loosen up a little on the second Handy-written number that was released, “Hooking Cow Blues.” The trombone and wind instruments play a bluesy stride – one can imagine Temple Drake doing at least a slow “shimmy” to its rhythm – and the wooden blocks played at the rear are audible through the acoustical tubes all the way throughout the performance. Handy in this song even throws in a few rattling cow bells – a lá the white “Original Dixieland Jass Band” as used in their recordings. Jogo that, you New Orleans musicians, he seems to be saying.

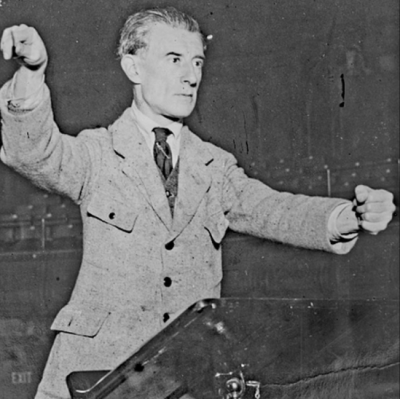

Interestingly, these 1917 recordings did not include any issuances of the “St. Louis Blues” indicating perhaps that Columbia did not then consider it sufficiently popular for a national, white audience. But the Columbia issues sold reasonably well, and, as Pace had hoped, resulted in more national publicity for the Memphis firm. Yet for Handy both personally and historically, this New York City trip was most significant for his first meeting with James Reese Europe, the adapter of “The Memphis Blues.” He, not Handy, was in 1917 the nation’s most pre-eminent black arranger of bluesy rags and marches. Handy that year was being praised at times nationally, but it was James Europe, who after his initial cross-over success with the Castles dance team (and his immensely popular, fox-trot arrangement of Handy’s lost song) who by the autumn of 1917 had accomplished far more than W. C. Handy in bringing African-American music and musicians to a national, white audience.

Europe had organized the first significant union and booking agency for black musicians, the Clef Club, and the biennial performances by its members as the Clef Club Orchestra of the City of New York – featuring one hundred musicians and twelve pianos – had drawn praiseful reviews from the white press. He also was now Lieutenant James Europe when he met Handy, having previously accepted a commission in the all-black 15th New York Infantry National Guard to organize its regimental band and to encourage recruitment among African Americans. Europe later would be the first black officer to lead African-American troops into combat at France. He would contribute significantly to Handy’s international fame as the “Father of the Blues” when during his convalescence from combat injuries he performed “The Memphis Blues” and other Handy songs with the 369th U. S. Infantry “Hell Fighters” band to wildly enthusiastic French civilians. They loved the Memphis composer’s songs, as Europe played them, which they termed le jazz hot.

Handy and Europe were a study in contrast when they met that autumn of 1917. Handy, as illustrated in the promotional line drawings for the Columbia releases, appeared as an avuncular, round-shouldered and professorially-looking middle-aged man, dressed in the uniform of the earlier century’s local brass bands. Europe, eight years younger and looking even more so, was “a big, tall man,” his friend and fellow musician Eubie Blake later recalled, and he habitually stood up very straight “like a West Point soldier.” A pair of rimless glasses gave Europe, despite his solid build, a studious look, almost as if he were the graduate student to Handy’s professor. Both had studied music formally. What these two Alabama-born composers and arrangers may have warily said to one another when they first met was not recalled by others, nor later in his memoir by Handy. But their encounter in 1917 was a turning point in the history of the blues, and of which of these two ambitious African-American men later would be remembered historically as its most pre-eminent practitioner. Tempo á blues was becoming faster.

*

Snakey Blues, by W.C. Handy’s Memphis Blues Band

The Memphis Blues, by James Reese Europe’s 369th U.S. Infantry “Hell Fighters” Band

_________________________

W.C. Handy: The Life and Times of the Man Who Made the Blues, by David Robertson, published by Alfred A. Knopf

__________

Excerpted from Alfred A. Knopf. Copyright (c) 2009 by David Robertson. All rights reserved.

*

This edition of Great Encounters was researched and published by Peter Maita on August 7, 2009. Portland, Oregon.