Great Encounters

Book excerpts that chronicle famous encounters among twentieth-century cultural icons

______________

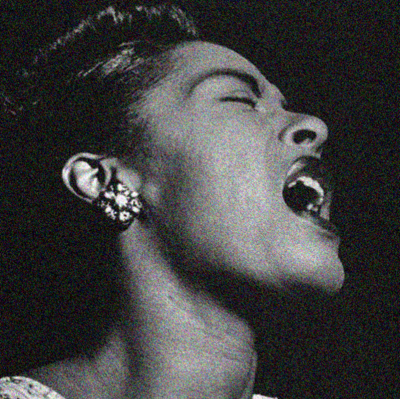

When John Hammond “discovered” Billie Holiday

______________

Excerpted from

The Producer: John Hammond and the Soul of American Music

by

Dunstan Prial

_________________________

On a cold, clear night in February, 1933, Hammond went on the town alone in search of music. Heading up Broadway toward Harlem in a Hudson convertible (he kept the top up in the winter), he fought traffic, but as he passed Columbia University, he was flying. At 133rd Street, he took a right and headed east toward Lenox Avenue. He pulled over after a few blocks and parked in a space a few doors up from a new speakeasy run by Monette Moore, the singer who had appeared with Ellington and Carter at the fund-raiser for the Scottsboro boys he had helped organize the previous fall. Moore had built a successful career in the 1920s, but the Depression had cut into sales of her records.

Hammond made the trip up to Harlem on this particular night, he later claimed, because he wanted to see Moore perform in the comfort of her own establishment. He was a fan of Moore’s and had also recruited her to sing at his short-lived vaudeville theater on the Lower East Side. It’s possible that Moore personally invted him up to her new speakeasy. Another version of this story holds that he headed to Moore’s that night because his friend the singer Mildred Bailey had told him there might be some other interesting talent on the bill. In any case, it would prove a watershed evening for him.

Speakeasies, especially those in the roughter sections of the city, opened and closed with the same frequency as cargo ships pulling in and out of New York harbor. A club owner might open and close in several different locations within the span of a few months, usually one step ahead of the authorities. To get inside Moore’s speakeasy, patrons walked down a flight of stairs and entered the dimly lit club through a front entrance manned by one or two large bouncers. The club hadn’t been open that long, and it wouldn’t stay open much longer.

After rapping at the door a couple of times, Hammond waited a few moments while the bouncer on the other side gave him the once-over from behind a thin viewing slot cut into the door at eye level. The bouncer at Moore’s that night didn’t recognize Hammond, but the young white guy with the flattop crew cut waiting in the cold was well dressed and seemed at ease in his surroundings. The door opened and Hammond walked inside. He made his way to the rear of the club and ordered a brandy to warm himself. Glancing around at the other patrons, mostly well-dressed blacks from Harlem’s upper crust but also a few white hipsters in Harlem for the night, he lit a cigarette and waited for the show to begin.

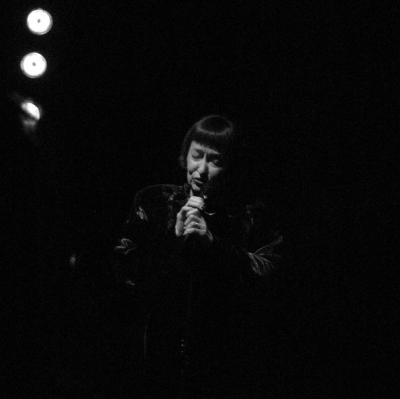

As it happened, Moore would not perform that night. She either was sick or had been called away as a last-minute substitute for Ethel Waters, for whom she was serving as understudy in a musical down on Broadway. But the sight of Moore’s replacement, Hammond later said, took his breath away. She couldn’t have been more than seventeen or eighteen years old. But her elegance and composure belied her youth. Dressed in an evening gown, she emerged from the dressing room and moved gracefully but with purpose across the floor through the array of small tables. She stopped at the piano, where she conferred quietly with her accompanist. Hammond was immediately struck by her presence; she commanded attention — and she hadn’t even begun to sing.

Then she did sing — and it was extraordinary. “I just absolutely was overwhelmed,” Hammond told the disc jockey Ed Beach in a 1973 interview. One of the first numbers she did was a silly, slightly suggestive tune called “Wouldja for a Big Red Apple?” “She was not a blue singer, but she sang popular songs in a manner that made them completely her own. She had an uncanny ear, an excellent memory for lyrics, and she sang with anexquisite sense of phrasing. She always loved [Louis] Armstrong’s sound and it is not too much to say that she sang the way he played horn. . .I decided that night that she was the best jazz singer I had ever heard.”

When telling the story of how he “discovered” Billie Holiday, Hammond always cited serendipity as the primary factor in his chancing upon her that night. “My discovery of Billie Holiday was the kind of accident I dreamed of, the sort of reward I received now and then by traveling to every place where anyone performed,” he wrote.

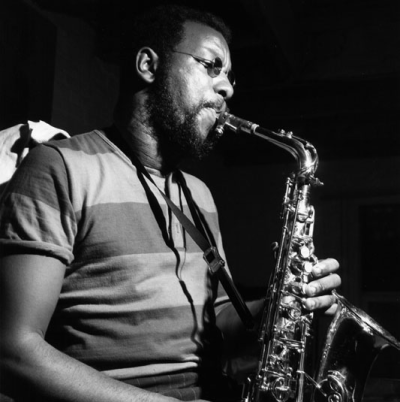

Holiday had been singing in small clubs around New York for at least two years before filling in for Moore that night in Harlem. Her first biographer, John Chilton, quoted a tenor saxophonist named Kenneth Hollon, who remembered playing club dates with her in a joint called the Gray Dawn on Jamaica Avenue in Queens in late 1930 or early 1931. Thus, despite her youth, she was an experienced performer at the time Hammond ran into her.

She was born in Baltimore on April 7, 1915, to teenage parents. The first paragraph of her 1956 autobiography reads famously: “Mom and Pop were just a couple of kids when they got married. He was eighteen, she was sixteen, and I was three.” Her name was Eleanora Fagan, and her childhood was apparently marked by neglect and incidents of physical and sexual abuse. By the time she arrived in New York in her mid-teens, she was streetwise beyond the experiences of most other girls her age. Moreover, she was a big girl who carried herself with the poise of a much older woman. Thus it’s easy to see how she was able to talk her way into professional singing gigs with much older musicians. She also had connections in the music industry: her father played guitar in Fletcher Henderson’s band.

At some point, probably in her early teens, she smoked her first joint. Apparently she liked it. It helped take the edge off an otherwise harsh existence. Liquor and, later, heroin also worked — for a while. But these weren’t factors when Hammond first met her.

Her performance at Moore’s speakeasy struck Hammond with the force of a Dempsey haymaker. She was, he observed, tall, full-bodied, and voluptuous to distraction. And her face was equally striking. The high, forceful cheekbones and broad, wide forehead recalled America’s ethnic history of the past two centuries, a story of generations of racial mingling among Negro slaves, white slave owner, and Native Americans. Her skin was the color and texture of fresh-brewed coffee, light with cream and sugar. “She weighs over 200 pounds, is incredibly beautiful, and sings as well as anybody I ever heard,” he wrote shortly after seeing Holiday for the first time. She also had magnificent bearing. Whatever the mood of the room, this singer was in complete control of it. It seemed to Hammond that she turned the traditional audience-singer relationship upside down. It was common at the time for singers to walk the floors of speakeasies and dance halls, accepting tips as they roamed from table to table. Singers generally acknowledged a tip with some small flourish, a slight bow, perhaps, or maybe a fingertip traced along the chin of a handsome man. Some singers might even linger and sing a few choice lyrics directly into the eyes of a blushing big spender. “Not Billie,” Hammond called. “I mean everything was improvised and her mood changed according to the stiff or not so stiff people who were at the tables.”

During a lush ballad her full, sensuous lips might shift slightly, offering a hint of a smile. Singing a more up-tempo number, she would fold her arms in front of her healthy bosom, and a scolding index finger might offer mock admonishment to an especially randy patron. The gestures were so easy and natural that they left Moore’s patrons feeling grateful that this singer had deigned to accept their tips.

Incredibly, all of these qualities paled in comparison to her actual singing. Hammond noted that her voice slipped into his ear just slightly — almost imperceptibly — behind the beat, a style that suggested her singing was merely an afterthought, a spontaneous response to the chance hearing of a beautiful melody. It was as if the song had wafted in through an open window, perhaps, and Holiday had instinctively joined in. And the voice had the same range of emotion as the young singer. It could be foreceful and confident one minute, then utterly vulnerable the next. It could be flirty and teasing, but always stopped well short of vulgarity. But it certainly wasn’t the strength of her voice that made it distinctive. There were plenty of singers around who could shake the rafters. Rather, there was a delicacy to it that required the listener to pay close attention. And its effect was lasting. The nightclub owner Barney Josephson once observed, “She never had a really big voice — it was small, like a bell that rang and went a mile.”

“She was seventeen when I first heard her, she was nearly eighteen,” Hammond recalled. “She was just unbelievable, she phrased like an improvising instrumentalist. She was the first singer I ever heard do that. She didn’t read music, didn’t have to. To me she was unbelievable.”

After that night at Moore’s, Hammond immediately set about promoting his new find, both through word of mouth and in his Melody Maker column. “For this month there has been a real find in the person of a singer called Billie Holiday [sic], step-daughter of Fletcher Henderson’s guitar player,” he wrote for his English readers. He spent the next few months following Holiday around Harlem with the bass player Artie Bernstein. To his dismay, he found that not everyone was as instantly convinced of her talent. “It took months for me to persuade anybody that Billie could be recorded,” he told Ed Beach many years later.

_________________________

The Producer: John Hammond and the Soul of American Music

by Dunstan Prial

__________

From THE PRODUCER: John Hammond and the Soul of American Music by Dunstan Prial, published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC. Copyright (c) 2006 by Dunstan Prial. All rights reserved.

Always thought Hammond first saw her at Pods and Jerrys, just few doors down the street on the same side. Doesn’t really matter as long as he found her!

It has been well established for 20 years that she was born in Philadelphia.

It has been well established for 20 years that she was born in Philadelphia.

I always found that part of Harlem intersecting in the 1980s my Granfather walked me down 133rd street The Hotcha sign was still up and he gave me a verbal history of the block in his days all that’s gone now tho