.

.

The cover of Escalator Over The Hill, recorded over a three year period (1968 – 1971) and released as a three album set by JCOA Records in 1971.

.

.

___

.

.

Escalator Over The Hill – Then and Now

by Joel Lewis

.

…..A few weeks ago, I was scrolling through Facebook Reels, taking a break from fine tuning some poems before launching them out into the submittable trough. I love the animal reels – cats and dogs getting along, overtly friendly and potentially rabid racoons, and my current obsession, the capybara, that hundred-pound rodent with a sweet disposition.

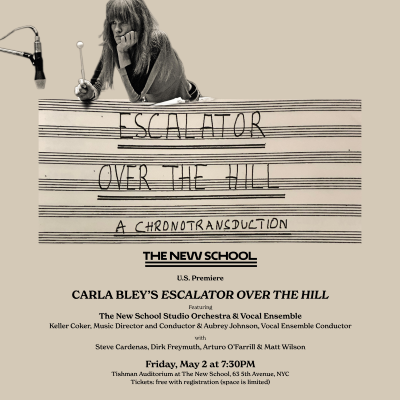

….. Just as I decided to return to my manuscripts, I clicked right once more and was presented an advertisement from the New School announcing the United States premiere performance of Carla Bley and Paul Haines’s unclassifiable masterpiece Escalator Over The Hill, which was to be performed by students from Mannes College of Music (now part of the New School) and students from its Jazz Program. I was curious to see if well-meaning student musicians could do justice to a score that was once inhabited by an improbable lineup of now-legendary players that ranged from Don Cherry to Linda Ronstadt to John Mclaughlin to Andy Warhol “superstar” Viva. Well, the tickets were free and the New School is just a block from the 14th Street PATH train from Hoboken – so why not? I quickly filled out the online application for a pair of tickets.

….. Escalator Over The Hill (EOTH) is that rare work that seems unstuck in time. Though composed and then intermittently recorded from the late 60s to the early 70s, it bears no marker of that very turbulent period. No traces of the Vietnam War, political assassinations, racial conflict or emerging Second Wave feminism (even though it was composed by a woman). In its time, it was widely praised and well-reviewed – including the unlikely triad of Rolling Stone, Penthouse and the Omaha World Herald. And at its initial release, this triple box LP set sold 5,000 copies – a decent amount for a record that received little airplay, released on a small label that specialized in avant-garde jazz, and that wasn’t performed live until more than twenty-five years later in Europe (and mostly in German cities). The reasons that this work wasn’t staged at the outset were mostly due to matters of financing such a large enterprise, as well as the state of jazz in 1971, when jazz in America was at something of a nadir. Most major labels had reduced or ceased their jazz programs, and among the jazz labels, Prestige and Blue Note were shifting to producing jazz/funk albums. As for the avant-garde jazz that Bley participated in, it remained a niche music primarily issued on musician-run labels and mostly distributed by New Music Distributors, an outfit run by Bley and her then-husband, trumpeter Michael Mantler.

….. Bley, herself, was associated with the modern jazz of the late 50s and early 60s. Through her marriage to pianist Paul Bley, she met Ornette Coleman, Billy Higgins, Charlie Haden and Don Cherry – who had briefly joined Paul Bley’s band that played at Los Angeles’ Hillcrest Club. In New York, Carla Bley’s compositions were recorded by Gary Burton, Art Farmer and the Jimmy Giuffre Trio, which for a time her husband was its pianist . She was also deeply involved in the activities in Downtown Manhattan’s free jazz community, most significantly forming the Jazz Composer’s Orchestra, which was to perform and record large scale pieces by composer-performers such as Leroy Jenkins, Clifford Thornton and Grachan Moncur III.

….. The path to the creation of Escalator Over The Hill seems to have been the result of two events in 1967. During that year, Carla Bley took part in a European tour that left her questioning her previous musical alliances. In a Downbeat magazine article, she told Howard Mandel that the music she performed with German free improvisers Peter Brotzman and Peter Kowald was “high energy, hateful screaming music” and because of this sonic experience, she felt “mad at jazz.” According to her biographer Amy C. Beal, Bley was not only “growing ambivalent about the expressive qualities of free jazz, but she started to question her relationship to the African American roots of jazz. She began cultivating a musical alliance with what she considered to be her true culture: European and European American music.”[1]

….. Around the same time of this musical revaluation, Bley’s friend Michael Snow – an important avant-garde filmmaker with close ties to the world of free jazz—introduced her to the newly-released Beatles album, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Bley was particularly taken in by the sonic audacity of the project, particularly the song “Day In The Life,” as well of the notion of a “concept album.”

….. Bley may have been one of the first jazz musicians to take post-Beatle rock music as a serious “adult” pop and not “kiddie music” (to use music critic Will Freidwald’s putdown). Many jazz musicians of the period were bitter with the rise of rock music since it had become a market force in the world of LP sales, previously dominated by classical, jazz and adult pop (think Frank Sinatra). At the time, 50’s rock and roll was the world of the 45-rpm single, only a minor part of the jazz market. When jazz musicians tried a reproachment with rock music it was mostly an unenthusiastic play at the youth market. Count Basie and Duke Ellington both recorded tributes to the Beatles; Grant Green covered “I Want to Hold Your Hand” with the enthusiasm of a man being led to a firing squad; Joe Pass did an album’s worth of Rolling Stone covers; and, of course, there was Gerry Mulligan’s white flag of surrender, his 1965 album If You Can’t Beat ‘Em, Join ‘Em, which featured his takes on unlikely vehicles for improvisation like “King of the Road” and “Downtown.” Mulligan, to his credit, did hire Hal Blaine for the session, a drummer who played on much of the rock music recorded on the West Coast. Bley heard the Beatles with a composer’s ear, not as part of a tidal wave that was causing major labels to close their jazz divisions, clubs to change their music policies and forcing jazz musicians to seek work in Europe. As part of a community of free jazz players who infrequently played and had to form their own record labels, Bley probably felt little economic impact in her scraping-by situation.

….. Under the influence of both her new musical priorities and her introduction to Sgt Pepper’s, Bley developed a large-scale project, A Genuine Tong Funeral, which she dubbed as a “dark opera without words” that is something of a prequel to Escalator Over the Hill. The project found sponsorship with the vibraphonist Burton, a mainstay of the RCA label’s jazz program who agreed to record her work under his leadership. In addition to employing mildly rock-ish guitarist Larry Coryell, his book – which mostly consisted of compositions by Bley, Michael Gibbs and Steve Swallow – made him a forward-looking leader who was one of the few jazz players of the period possessing a youthful following.

….. The work is essentially a chamber piece and the titles of the individual compositions – such as “Mother of the Dead Man,” “Grave Train,” and “The New Funeral March” – reflect the composer’s description of the work as an exploration of “emotions towards death, from the most irreverent to those of deepest loss.” Bley put together a sextet to work with Burton’s working quartet, some of whom – particularly tenor player Gato Barbieri and tubist Howard Johnson – would become key players on EOTH. This combined ensemble toured the United States performing A Genuine Tong Funeral, even performing at Filmore West in San Francisco, opening for the supergroup Cream. It was at this gig that Bley met the group’s bassist/vocalist Jack Bruce, who would become a very important component of EOTH.

….. A Genuine Tong Funeral was well received critically, receiving a five-star review in Downbeat and Gary Burton being named “Jazzman of the Year” by the magazine in 1968. At 25, he was the youngest to win that award. Burton’s core audience seemed less impressed and, perhaps, put off by the austerity and seriousness of the album, as it didn’t sell particularly well. . It was out of print by the early 70s and during the CD era was only available in European markets. Happily, the album – along with nearly all of Burton’s RCA output – can be found on streaming services.

….. The genesis of EOTH, according to Bley, began around 1967, when she was writing a piece of music called “Detective Writer Daughter.” Her friend, Paul Haines, mailed her a poem and Bley was amazed how “mysteriously” it fit with the work. “We decided to write an opera together,” Bley wrote in the text “Accomplishing Escalator Over The Hill” (1972), “or, rather, apart, as he was then living in New Mexico and about to move to India. The term ‘opera’ was used rather loosely from the start, an overstatement by two people who didn’t have to watch their words. We ended up calling it a chronotransduction, which was a word coined by Sherry Spieth, a scientist friend of Paul’s, although we still called it an opera for short.”[2]

.

….. This is a good time to write about EOTH’s librettist, Paul Haines (1932-2003). He is usually given short shrift in discussing EOTH, other than declaring his lyrics incomprehensible, then moving back to discussing Bley’s score. Haines was a Zelig-like figure of the free jazz movement, writing liner notes for everyone from Paul Bley to Evan Parker. As a producer he put together the group of Albert Ayler, Roswell Rudd, John Tchicai, Gary Peacock and Sunny Murray for the soundtrack of the Michael Snow film New York Eye and Ear Control – a recording considered an early example of free improvisation. But as a writer, he was a bit more shadowy. Most of his poetry was published in a few very small press magazines, and his only book of poems published in his lifetime was a 1981 chapbook Third World Two. Also, after a peripatetic life, he moved to Fenelon Falls, Ontario with his wife and raised a family of three children, one of which is vocalist Emily Haines of the Metrics (she recorded a song called “Detective Daughter” that nods to her father’s poetry). He was quite active during his Canadian years, but little of it filtered below the 49th Parallel. There is a posthumous collection of Haines’s writing, Secret Carnival Workers, edited by his friend, the music journalist Stuart Broomer, that offers a comprehensive look at his writing.

….. Broomer noted in his introduction that Haines made little reference to his poetry influences. He seems to be part of any “scene” other than inhabiting the world of the jazz beau. As a young man he heard Charlie Parker, and went to New Orleans where he posed in a photo with Dixieland legend George Lewis. But given that Haines studied French Literature and taught the language for years in the Fenelon Falls school system, it seems that he was familiar with French Surrealism, especially that of Benjamin Péret, André Breton and Francis Picabia. Given that he was living in lower Manhattan in the early 60s, I suspect he was familiar with the New York School of Poetry that leaned heavily into surrealism, as well as experimentation. Broomer additionally opines on why Haines’s poems served composers like Bley so well, writing that “Haines is collaborative and reciprocal. The strength of his writing begins in its openness and wit and develops in its brevity and compression: it reveals its resilience in its author’s extreme openness to adaptation. It is antithetical to most of the poetry that has been linked to jazz, poetry that has tended to the diffuse and expressionist. Haines’ poetry on the other hand is precise and absolute.”[3]

….. While Haines was mailing in his poems (he and Bley collaborated in person only briefly), Bley continued setting her collaborator’s words to her music – and this was the first time lyrics were a part of her compositions. “Paul would send me a batch of lyrics from India,” Bley wrote, “and I would put them on the piano and stare at them for hours. Sooner or later certain lines would seem to have a melody to them. Then it would just be a matter of working at it, with the form and rhythm of the words leading the way.”[4]

….. After three years of collaborating, twelve major pieces of music had been composed. From the outset, Escalator Over The Hill was the working title of the project. With a title set and solid body of work completed, the question was who Bley was going to get to perform it.

.

….. If jazz fans know anything about EOTH, it is the insanely diverse cast of musicians that performed on the recording. Some of the players, like Gato Barbieri, Roswell Rudd and Don Cherry, were members of the Jazz Composers Orchestra. Others, like trombonist Sam Burtis and tuba player Howard Johnson were primarily denizens of the studios and orchestra pits. Others, like altoist Jimmy Lyons and vibist Karl Berger, were key members of the free jazz community. Then there were the outliers like Metropolitan Opera mezzo-soprano Rosalind Hupp and Andy Warhol “superstar” Viva, who was the narrator of EOTH. My friends and I decided to put down the serious money (for a teenager) on the 3-LP set based on the lure of hearing John McLaughlin and Jack Bruce “jamming.” McLaughlin’s first Mahavishnu Orchestra album – The Inner Mounting Flame – was released the same year as EOTH.

….. The one musician on the list of the 53 musicians that likely caused listeners to doubletake while reading the LP credits was Linda Ronstadt. As a member of the Stone Poneys, the then 21-year-old singer had a top 20 hit with “Different Drummer,” which was written by Monkees member Michael Nesmith. After leaving the band, she recorded two country-oriented solo albums that were received well in publications like Rolling Stone, but sold only modestly. Bley stated that she contacted Ronstadt through the recommendation of EOTH’s house drummer Paul Motian, best known for his tenure in the Bill Evans Trio. How did Motian know of Ronstadt? It’s possible he encountered Ronstadt while touring with Arlo Guthrie – who Motian played with at Woodstock. She recorded her parts in Los Angeles and said in interviews that it was the hardest vocal work she had ever done.

….. Ronstadt was cast in EOTH as “Ginger,” an expatriate who resides in “Cecil Clark’s Hotel,” located in Rawlapindi, Pakistan. The other major character is “Jack,” as performed by Cream bassist Jack Bruce. There were twenty other figures bearing oddball sobriquets such as “Ancient Roomer,” “Yodeling Ventriloquist,” and “Sand Shepherd,” memorably performed by Don Cherry in his first vocal recording. There was a further collection of “Phantoms, Multiple Public Members, Hotel people, Women, Men, Flies, Bullfrogs, Minesweepers, Speakers, Blindman” vocalized by a cast that included Shelia Jordan, Jeanne Lee, Paul Jones (ex-Manfred Mann), Charlie Haden and the composer herself.

….. The 24 instrumentalists were placed into various units, among them a 19-piece “Orchestra and Hotel Lobby Band.” Michael Snow played trumpet in the “Original Hotel Amateur Band,” a nine-piece unit whose name was a nod to the Original Dixieland Jazz Band. Don Cherry was the dominant voice of the eight-piece “Desert Band,” which played Middle-eastern inflected music. “Jack’s Travelling Band” was where McLaughlin and Bruce played proto-fusion jams. “Phantom Music” was responsible for ambient sounds achieved with bells, chimes, prepared piano and a Moog synthesizer

….. Bley was a multitasker before the term came into common usage. In this, her first album released under her own name, Bley was more than “hands on.” She oversaw almost every aspect of the project (save writing the lyrics) – composing, arranging, singing, conducting, playing keyboards, mixing and editing the tapes – and even preparing the master. She also cajoled studio and rehearsal time from RCA studios, Joseph Papp’s Public Theater, and Jonas Mekas’s Filmmaker’s Cinematheque’. She was fundraising throughout, writing to people like Yoko Ono and The Who’s Peter Townsend with little success in securing loans until a crucial loan provided by a friend of Paul Haines enabled the album to be completed and released on the JCOA label. And unlike the many musician-run labels that New Music Distributors handled, EOTH had a gold-embossed cover and an LP-sized booklet that contained the libretto and photos by Todd Pappageorge and Gary Winogrand.

….. Despite the positive reviews, awards and Bley receiving a Guggenheim Fellowship, EOTH slowly receded from view. There was a coda of sorts to the project in an album called Tropic Appetites (recorded in 73/74 but not released until ’78), which again featured lyrics by Haines and an octet backing English vocalist Julie Tippetts that included seven veterans from EOTH. Neither project was performed live at the time of their release. There was talk of filming a staged performance of EOTH, but nothing came of it. A movie produced by Steve Gebhardt documented the recording of EOTH, but its 1999 release had a very limited distribution. There are tantalizing You Tube clips of it, but the film appears to be unavailable now. Karen Mantler, Bley’s daughter, responded to my email query to inform me that the director is now deceased and she is unaware who currently has rights to the film.

….. Also, by the late 70s, Bley again began rethinking her approach to making music. The follow-up to Tropic Appetites, Dinner Music (1977) features compositions previously recorded by Paul Bley, Art Farmer and Gary Burton, and performed under her leadership for the first time. Additionally, she utilized pre-recorded rhythm tracks performed by Stuff – a popular NYC-based funk band whose members included Steve Gadd and Richard Tee. Bley began working with musicians associated with the UK art-rock scene like Robert Wyatt, Gary Windo, Hugh Hopper and Elton Dean of Soft Machine, and even Nick Mason, the Pink Floyd drummer. Her album Live (1982) was a commercially successful album and established her band, a decet, as a popular club and concert attraction. The album features a quasi-cheesecake photo of Bley and the members of her band who were by then all solid mainstream players. Bley also recorded a trio of albums in the mid-80s that featured Hiram Bullock – best known for his tenure with both David Sanborn and the David Letterman Show’s house band – that were poorly reviewed and dismissed at the time as “lite jazz” but have been reassessed more favorably in recent years. She has toured with her big band as well as with intimate units of duos and trios. She told Amy C. Beal that she was now inspired more by Count Basie than by the Beatles, Anton Webern, or Kurt Weil and that she had moved far away from the “mavericky” aesthetic of EOTH. “Jazz is where my heart now lies…”, she declared to Beal, “I just want to be a great jazz composer.”[5]

.

….. There was a scrum of purposeful activity the night of EOTH’s American premiere at the New School’s University Center, a striking 16-story edifice designed by Skidmore, Owing and Merrill. Student volunteers were cheerily managing the multiple lines that formed outside the entrance on Fifth Avenue. My “plus one” finally arrived – a painter friend and fellow weird-music-lover named Sasha who I ran into at the Columbus Circle Whole Foods the day before and offered her a ticket. For a change, I was in the “right line.” We made our way downstairs into the state-of-the-art Tischman Auditorium and found seats up front, right next to one of the many cameras filming the performance..

….. As the auditorium filled up, I noticed it was mostly an older crowd who looked like latter-day versions of the people I sat next to in places like the old Knitting Factory, Soundscape, Roulette and the Kitchen, where enthusiasts of New Sounds congregated in the 80s and 90s. I even ran into some people I knew personally from that time, including the poet and essayist Geoffrey O’Brian. We were curious to discover how EOTH would sound without the presence of distinctive, iconoclastic players like Gato Barbieri, Don Cherry and Perry Robinson – the kind of musicians serious listeners can identify in within a note or two. Walking to my seat, I waved hello to Bruce Gallanter, co-owner of the Downtown Music Gallery, a mainstay of the New Music scene. If one awoke up with a hankering for Fujianese food and any of the 700+ CDs from John Zorn’s Tzadik label, a trip to the DMG location in the non-tourist part of Chinatown could satisfy both urges.

….. The New School saw this as a “big event” – there were stories in the New York Times as well as on National Public Radio. A college bigwig welcomed the audience and introduced others in the audience. The New School had just gone through a faculty strike (most of whom were adjuncts), and unflattering stories about the big salaries for administrators and the fancy brownstone that the school bought for their president were being reported.

….. The lights finally went down and the band commenced. The ensemble consisted of members of Mannes College of Music (whose alumni include Burt Bacharach, Bill Evans and Federica Von Stade) and School of Jazz and Contemporary Music, a popular program for foreign students given its Manhattan location. An eleven-member vocal ensemble was also assembled. What struck me about this performance was that without distinctive performers like Barbieri and McLaughlin, I was able to put my focus on the composition itself. There was a flow to the piece that is not as present as on the recording, which is knit together from numerous sessions. Additionally, the benefit of having an ensemble of classically-trained singers was evident – Bley used a mix of distinctive singers like Ronstadt, Jeanne Lee and Sheila Jordan, plus a crew of a non-professional songbirds. The stand-out singer was Andrew Sweeney, who channeled the brio of Jack Bruce’s voice in the role of Jack.

….. As the piece began to wind down, i began to be curious about how the ensemble would conclude the piece. On the LP version, EOTH ends in a drone that plays on and on thanks to a locked groove that won’t allow the pickup to eject (the drone on the CD lasts 18 minutes). Some versions of Sgt Pepper’s featured a locked groove, as did Lou Reed’s instrumental noise fest Metal Machine Music. How will this conclude on stage?

….. As the final piece “… And It’s Again” drew to an end, one by one the members of the ensemble proceeded to leave, picking up their jackets they had hung up at the outset of the concert. Finally, the stage was empty, with the drone playing on (and it was the actual drone heard on the recording provided by the Watt Works record label). The audience was silent for a bit, not sure if the ensemble was coming back to take a bow. Finally, a huge wave of applause and a standing ovation erupted upon the crowd’s realization that the performance had reached its logical conclusion.

….. At the reception afterwards I spoke to several of the young performers who all looked exhilarated that they had pulled off the demanding work. None of them were aware of EOTH before they signed up to perform it. I even got in a few moments with the conductor and musical director, Keller Coker, who was ecstatic with the reception of the full house and was thinking of a repeat performance down the road.

….. Sasha and I left and walked west on 14th Street, and while waiting at the light to cross the street, several guys approached us. One of them asked, “Were you at the concert at the New School?” We talked about about how much we loved the music we just heard, and, like the young musicians, none of them were even aware of EOTH until tonight.

….. We then encountered Bruce Galanter, who was ecstatic about the concert as well. It felt like I was back in my twenties, running off to shows all over New York and New Jersey with my music buddies, rummaging LP bins in the many record shops that used to line 8th Street in Greenwich Village and all-night listening sessions in my basement lair, fueled by coffee and sliders from a nearby White Castle.

….. Hopefully the good word about this performance sparks interest in a professional unit taking a crack at it. The version of EOTH t hat was performed at the New School is based on a version prepared by Jeff Freidman so that “a concert version of this work is now possible without the author’s participation”.[6] This is a work that needs to be experienced live and, perhaps, even staged as a realized “jazz opera” or “chronotransduction.”

….. It is also important that Carla Bley’s accomplishments as a composer and a musician be properly exposed and recognized. Despite writing and performing music that is decidedly within the mainstream of contemporary jazz, she seems to be treated as a bit of a jokester. Her interviews were often hilarious, and her official website is full of gags and in-jokes. And, she lacked the oracular voice that many jazz figures speak in. But consider this: she issued all her recordings through her own label and all her albums (save one) are available. She also had her own music publishing company, and even recorded most of her albums in her Grog Kill Studios.

….. And as for what EOTH is all about, I think Amy C. Beal makes the case for why it should matter for the contemporary jazz listener:

..…“The work as a whole seems simultaneously to assimilate and annihilate rock gestures, jazz harmonies, and classical structures. By nature of its absolute autonomy, Escalator over the Hill also seems to thumb its nose at all musical authorities and institutions, particularly the recording industry. In this sense it is perhaps the quintessential antiestablishment statement of its time.” [7]

.

.

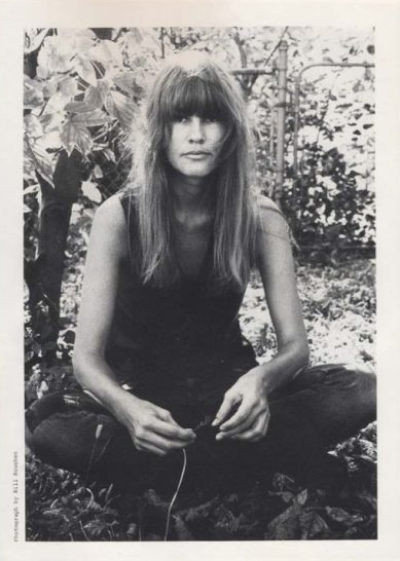

photo courtesy Bill Roughen

This Bill Roughen photo of Carla Bley appeared in the booklet to Escalator Over The Hill.

.

.

___

.

.

Joel Lewis’s Well You Needn’t, a book of poetry and memoirs about 55+ plus years of listening to jazz, was published by Hanging Loose this December. He has written about all sorts of music and spent a decade writing program notes for NJPAC in Newark, New Jersey, getting to interview many of his musical heroes. He resides in Hoboken, New Jersey.

.

.

___

.

.

A poster announcing the May 2, 2025 performance of Escalator Over The Hill at The New School

.

.

Watch Jack Bruce recording a vocal part for EOTH

.

.

Watch Jeanne Lee record a vocal part for EOTH

.

.

Watch a brief rehearsal video of EOTH

.

.

Watch Carla Bley lead a 1998 performance of EOTH

.

.

Watch the complete May 2, 2025 performance of the New School Studio Orchestra & Vocal Ensemble performing EOTH

.

.

___

.

.

Footnotes

[1] Beal, Amy C. Beal, Carla Bley (American Composer)), , Univ of Illinois Press, p.34

[2] This text was included as part of the program at the New School Performance. It is available online at Ethan Iverson’s Do The Math blog

[3] Broomer, Stuart, editor. Paul Haines: Secret Carnival Workers. Toronto, Coach House, 2007

[4] From Accomplishing Escalator Over The Hill

[5] Beal,ibid, p. 89

[6] From the Wattextra website wattextra.com/eoth.html

[7] Beal, ibid., p43

.

.

___

.

.

Click for:

“Saharan Blues on the Seine,” Aishatu Ado’s winning story in the 68th Jerry Jazz Musician Short Fiction Contest

Information about how to submit your essay, poetry or short fiction

Subscribe to the (free) Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter

Helping to support the ongoing publication of Jerry Jazz Musician, and to keep it commercial-free (thank you!)

.

___

.

.

Jerry Jazz Musician…human produced since 1999

.

.