.

.

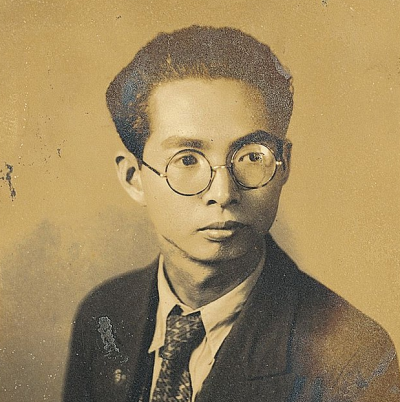

Alyn Shipton,

author of

Hi-De-Ho: The Life of Cab Calloway

.

___

.

.

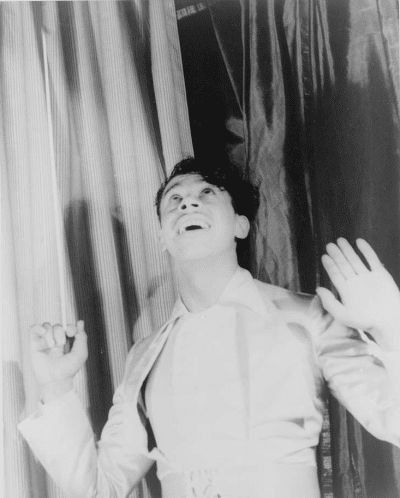

Clad in white tie and tails, dancing and scatting his way through the “Hi-de-ho” chorus of “Minnie the Moocher,” Cab Calloway exuded a sly charm and sophistication that endeared him to legions of fans.

In Hi-de-ho, author Alyn Shipton offers the first full-length biography of Cab Calloway, whose vocal theatrics and flamboyant stage presence made him one of the highest-earning African American bandleaders. Shipton sheds new light on Calloway’s life and career, explaining how he traversed racial and social boundaries to become one of the country’s most beloved entertainers.

Drawing on first-hand accounts from Calloway’s family, friends, and fellow musicians, the book traces the roots of this music icon, from his childhood in Rochester, New York, to his life of hustling on the streets of Baltimore. Shipton highlights how Calloway’s desire to earn money to support his infant daughter prompted his first break into show business, when he joined his sister Blanche in a traveling revue. Beginning in obscure Baltimore nightclubs and culminating in his replacement of Duke Ellington at New York’s famed Cotton Club, Calloway honed his gifts of scat singing and call-and-response routines. His career as a bandleader was matched by his genius as a talent-spotter, evidenced by his hiring of such jazz luminaries as Ben Webster, Dizzy Gillespie, and Jonah Jones.

Drawing on first-hand accounts from Calloway’s family, friends, and fellow musicians, the book traces the roots of this music icon, from his childhood in Rochester, New York, to his life of hustling on the streets of Baltimore. Shipton highlights how Calloway’s desire to earn money to support his infant daughter prompted his first break into show business, when he joined his sister Blanche in a traveling revue. Beginning in obscure Baltimore nightclubs and culminating in his replacement of Duke Ellington at New York’s famed Cotton Club, Calloway honed his gifts of scat singing and call-and-response routines. His career as a bandleader was matched by his genius as a talent-spotter, evidenced by his hiring of such jazz luminaries as Ben Webster, Dizzy Gillespie, and Jonah Jones.

As the swing era waned, Calloway reinvented himself as a musical theatre star, appearing as Sportin’ Life in Porgy and Bess in the early 1950s; in later years, Calloway cemented his status as a living legend through cameos on Sesame Street and his show-stopping appearance in the wildly popular The Blues Brothers movie, bringing his trademark “hi-de-ho” refrain to a new generation of audiences.

More than any other source, Hi-de-ho stands as an entertaining, not-to-be-missed portrait of Cab Calloway–one that expertly frames his enduring significance as a pioneering artist and entertainer.#

Shipton joins Jerry Jazz Musician publisher Joe Maita in an April 6, 2011 conversation about Calloway.

.

.

___

.

.

photo by Carl Van Vechten/Library of Congress

“Clad in white tie and tails, dancing energetically, waving an oversized baton, and singing ‘Minnie the Moocher,’ Cab Calloway is one of the most iconic figures in popular music. He was the first great African American vocalist in jazz who specialized in singing without also doubling on an instrument, and he was also a conductor and bandleader who assembled a series of remarkably consistent hard-swinging ensembles. By always striving to hire the best musicians and arrangers, he took the art of big band playing forward consistently from the start of the 1930s to the end of the 1940s. The tenor saxophonist Chu Berry made some of his finest records in the Calloway band, as did trumpeter Jonah Jones, saxophonists Ike Quebec and Eddie Barefield, and drummer Cozy Cole. At its peak in the late 1930s and early 1940s, Calloway’s was the highest earning African American orchestra and, by virtue of its biggest hit ‘Minnie the Moocher,’ also one of the few to have broken through to the general public with a million-selling record. People loved Cab and his antics for what he was, irrespective of color. In later life, Cab transformed into an elegant and sophisticated star of the musical theater, but from the 1930s to the 1990s, he never forgot how to ‘hi-de-ho,’ and win over a crowd.”

– Alyn Shipton

.

.

Watch Cab Calloway perform “Hi De Ho”

.

___

.

JJM What was your critical opinion of Cab Calloway before writing Hi De Ho?

AS Before I wrote the book I had a much lower critical opinion of him than I do now. While writing the book I listened to virtually everything that one can get hold of. Originally, I was very much influenced by the school of criticism that thought of him as an impediment to a very fine band. But the more I listened, the more I realized that he was a very fine bandleader. Although he didn’t own all of it -Irving Mills was his major financial partner – Cab really did shape and mold that band into something that was quite exceptional for its time, and I think that was one skill.

The other skill I really came to appreciate through researching the book was the variety and depth of his talent as a singer. I wrote at length about some of the unusual things he does, particularly how he incorporates different layers of scat singing where he can assume different persona, in some cases having not one but two conversations with other mythical characters within the course of a song, which is a very rare gift. An awful lot of vocalists who came after him, from early imitators like Billy Banks right the way through to people like Louis Jordan and Slim Gaillard, owed a huge amount to Cab. That’s the major critical reevaluation that happened after starting the book.

JJM Concerning Cab’s musical complexity, when describing his recording of “St. Louis Blues,” you wrote, “These chart the progress of Cab and the band as they found a natural musical language and style together. In due course, he would roll into this singing an astonishing range of allusion, consolidating Armstrong’s scatting, timing and phrasing, but also looking beyond jazz to a wider set of influences that encompassed Jewish cantors, country blues singers, and fast-talking low-life street characters.” This is a style that sets him apart from the typical jazz musician of his era…

AS Yes, I think so. I think the other thing about him is that he was clearly not backward educationally – after all, his parents had ambitions for him to be a lawyer. He may have been lazy and he might have wanted to go off and do things at the racetrack that kept him from going to school, but he was a very bright man from an early age. That’s reflected in the way he put songs together and the way he talks and his extraordinary range. On a recording like “Nagasaki,” for example, one minute he is doing little snatches of an Armstrong vocal, then he’s singing “Them cats will get you,” which just flies past, and there are all these other wonderful allusions to food, and to the way people are living. It’s like a very compressed version of some of the comments you get in a Fats Waller song, but whereas Fats would sort of interject these into his lyrics as he was playing, probably talking to his side men in the studio, with Cab you get it compressed into a sort of pate, if you see what I mean. There is a tighter range of allusions in a shorter space of time.

JJM You consider “Nagasaki” to be one of his greatest vocal triumphs and one of the most remarkable vocal performances in jazz…

AS Yes, it’s a shame that Columbia didn’t record it better, and it would have been great if RCA had recorded it because those RCA recordings are so beautifully done. It’s sad that we don’t have it so perfectly preserved as that wonderful remake of “Minnie the Moocher” he did for RCA, and “The Scat Song” and things like that where you can hear every nuance of the song.

JJM What was his first musical ambition?

AS I’m not sure that he didn’t think that he could be a drummer to start with, because there are all these stories of him playing the Arabian Tent Club in Baltimore as a drummer, and singing was something that crept in. The banjo player Elmer Snowden said that “Cab was no drummer,” although that may have been said with a certain amount of sour grapes. I have a feeling that Cab pretty quickly realized that if he was going to make his fortune it was going to be as a dancer, a stage personality, and a singer, and not as either a drummer or an alto saxophonist.

JJM You devote much of the story of his young adult life to the influence his sister Blanche had on him…

AS I’m convinced that she’s the great undiscovered story that this book has started to shed some light on, and I really hope now that someone will go out and research a full biography of Blanche Calloway, because she’s a fascinating figure. You can hear the evidence of her influence. She recorded a song called “Just A Crazy Song,” which was recorded before she could have possibly heard Cab’s recording of “Minnie the Moocher.” The songs were recorded six weeks apart at a time when it took longer than that to simply press and manufacture a record. So I think we can be pretty sure that she was doing an act – which included “Hi-De-Hoing” and shout-backing and many of the things that we hear in Cab – way before he was.

JJM She recorded with Louis Armstrong in November of 1925…

AS Yes that’s right, and those are interesting. When I was a kid, there were LP’s called Louis and the Blues Singers which were collections of him doing sessions in Chicago with blues singers passing through town, and Blanche Calloway stands out to me as one of the more unusual. I think it’s because there’s a slight “actressy” quality in her voice, which I talk about in the book. She had the ability to assume the character she was singing about, and that’s certainly something she passed on to Cab, and you hear that very early on in that first 1925 recording with Louis.

JJM What were her limitations as a performer?

AS Frankly, I think she was a one trick pony. I think she could do the shout-back-and-response stuff generally from the position of an adopted persona, but she didn’t have much range beyond that. You can’t really imagine her singing a ballad and meaning it unless it’s a lovelorn song where she’s putting herself into the character of the girl who’s been cheated on. On the other hand, Cab had an extraordinary ability to inhabit the lyrics he was singing about. When you hear him singing “Hi-De-Ho Man, That’s Me,” you can imagine him almost being a Baptist preacher with that amazing cantonal singing. While you can’t imagine Blanche approaching that range, she did manage to be a very gutsy and flamboyant female performer on stage who did have an act that worked extraordinarily well with the public, and I think that flamboyancy is what Cab learned from her. He took the “Hi-De-Ho” persona and the idea of engaging with the audience and using the whole African American tradition of call and response, and he did it all brilliantly, but he picked it up from her. I think she never quite got as far beyond that as she could, but of course she became a millionaire in her own right by selling cosmetics to African American women in later life.

JJM The Chicago Tribune critic Ashton Stevens called Plantation Days the “…fastest and best show I have seen in years.” Another critic said it made Shuffle Along look like a “funeral procession.” What was Cab’s role in this performance?

AS Initially he wanted to use it as a means to get to New York so he could see his newly-born daughter. The story is that he fell in love with his girlfriend, Zelma Proctor, while he was at school. Unfortunately, she became pregnant. She was very sensible and decided that marrying someone while still a teenager wasn’t the thing to do – especially to a hotshot like Cab – but, quite surprisingly, he took his responsibilities very seriously. When the baby was born, he needed to get to New York to see her and also to give her some money.

So when his sister breezed into Baltimore in this show called Plantation Days and said that there was a vacancy in a vocal quartet called The Crackerjacks, he took it upon himself to join. Even at that stage he was such a good singer and had such a big personality that he quickly worked into the act and was able to tour with the group. We know that the show with him in it was playing at the Lafayette Theater in Harlem just about the moment his daughter was born. Camay Calloway, who was very helpful to me while I was writing the book, arrived in 1927 at the very moment that Cab’s career was taking off. I think it’s an interesting idea that his career might not have taken off had she not been about to be born. She said to me she’d never thought of it like that, but once I pointed it out to her it seemed very obvious.

JJM He lived in Chicago during this time…

AS Yes, but he regularly sent money to New York. Blanche was in New York quite a lot, where she appeared at a number of clubs, and she kept an eye on the baby and sent news back to Cab about her. But Cab was definitely doing very well in Chicago so he stayed there, singing mainly at the Sunset, which is where Earl Hines and Louis Armstrong also performed – neither of whom really coincided with Cab for very long, although they did overlap for a few weeks.

JJM Describe the Sunset Cafe when Cab played there?

AS It was originally built as an automobile garage, so it was a big barn of a place. It is a hardware store today, and what survives from the Sunset are murals of dancers that look a bit like the extraordinary Harlem renaissance paintings of Aaron Douglas that are up in the Schoenberg Institute in Harlem. So, imagine this large, cavernous club with tables and chairs around it, a dance floor, and the band actually on the same level as the dance floor. When they talked about a “floorshow,” they were actually talking about a show that simply spilled onto and was part of the dance floor.

JJM The audiences were mixed race?

AS In Chicago that was possible. William Kenney’s marvelous book about the jazz age in Chicago gives us an idea that the city fathers wanted to defuse any kind of racial aggression, so one of the things that they turned a blind eye to was integrated audiences – and this was at a time when that would have been rare in other cities in the States.

JJM The great stage performers of the era, Bert Williams and George Walker, helped, in your words, to “redefine how songs, comedic monologues, and dance routines could be delivered, with a mastery of timing and nuance that was related to the everyday speech patterns of the African American audience.” To what degree was Cab influenced by Bert Williams and George Walker?

AS Well, I think a lot. In the book I write about Cab being their two personae rolled into one, because Walker was the flashy dressed, very smart looking, aspirational African American, while Bert Williams’ character was, to some extent, the country bumpkin with a certain amount of urban street smart layered on as well. They were probably the first black vaudeville act whose routines became nationally known through gramophone records so I think that Cab, consciously or not, adopted a lot of Bert Williams’ routines.

Williams and Walker were revered by members of Cab’s band. For example, Danny Barker – a key member of the band for nine years – owned a pair of Bert Williams’ shoes, which were lovingly brought out and shown to me on one of my first visits with him in New Orleans. He told me that these entertainers had had a really significant place in all their lives and that the band would have known their routines and very much revered the performers.

JJM You also point out that, “Another common element with Cab’s vocal storytelling about Minnie (“the Moocher”) was that both Williams and Walker delivered songs which contained coded linguistic messages that bypassed a white audience, but were picked up immediately by their African American audiences.” So they were also influential to Cab in that regard because coded messages being sung to an African American audience was so prominent in Calloway’s writing.

AS Yes, absolutely, and that’s never gone away. It is still going on in hip-hop today, which is a point I make at the end of the book. I’ve been taken to task by some jazz critics who ask how on earth I can make a link between Cab and that “dreadful hip-hop” stuff? I actually see this as all part of a continuity, which begins way before Williams and Walker. Early recordings sold to the black public in the United States were everything from sermons to comedy, so, it wasn’t simply a musical disc market. As jazz enthusiasts who are also writers about jazz tend to look at the world through myopic spectacles and don’t always remember that the gramophone buying public were buying records of all kinds of other stuff, not just music. Not to be putting down my colleagues, but I do sometimes think that they live in a hermetically sealed bubble in which only jazz goes on.

JJM His performances – now easily accessed online – are evidence of his influence on generations of performers as well…

AS Yes, you can see a connection with the generation before the hip-hoppers – entertainers like Gregory Hines, Richard Pryor, and to some extent Eddie Murphy – because of the way they moved, the way they told jokes, and the way they sing, all of which are very close to the way Cab performed as well.

JJM When did he first discover that he had a talent for leading a band?

AS Leading a band was somewhat accidental. While Cab was Master of Ceremonies at the Sunset, the house band – what later became the Alabamians – was led by a musical director, Marion Hardy, who wasn’t very good at his job. Cab decided to rehearse his own numbers with the band and realized immediately that he had a talent for directing the band. It was a “light bulb moment,” where he realized that he could not only be an M.C. and occasional vocalist and a stand-in for other acts when they didn’t show up, but he could be the director of the house band as well.

This led to an interesting moment because when the house band was asked to make room for another band to come in, Cab felt that his loyalties now lay with the musicians he directed and not with the club, so he chose to leave. That’s a really interesting decision, because he could have stayed in Chicago where he could have remained a very highly paid, very popular individual, but instead his heart and mind were in directing a band. I thought after the book was published that maybe I didn’t make enough of that choice he made, which is a really extraordinary decision, if you think about it – to leave a very safe job as the maitre d’ of an incredibly popular nightclub and go off on the road with a band that really had no prospect of getting much in the way of gigs.

JJM Yes…Throughout the book you made a point of pointing out a bond that existed between himself and his band members, suggesting that he would, “stick up for them and lead them through thick and thin.”

AS Yes, that “thick and thin” comment was as a result of a situation that took place during a tour of the South, where bands routinely would be ripped off by clubs and left stranded without cash. Cab decided his band was not going to be ripped off and insisted on being paid in cash. They took the proceeds of the box office and hid the money in their instrument cases – so much money that Doc Cheatham said they had never seen so much before. There was literally thousands of dollars in one-dollar bills stuffed into the drum cases and guitar cases, and they carried their instruments separately because they were so worried about the money being stolen. Once Cab said that was the way they were going to be paid, everybody rallied around him and Cab got them paid. Even though men in the band like Garvin Bushel, Ben Webster and Dizzy Gillespie were skeptical about Cab’s musical abilities, all of them recognized that when it came to the actual business of leading a band, he was extraordinarily good at it.

JJM Another turning point in his career was “The Million Dollar Affair in Musical Talent,” a big band battle held at the Savory Ballroom in May, 1930 that included the bands of Duke Ellington, Fletcher Henderson and Chick Webb. How did this event effect his future?

AS That was a fantastically important experience, because the Missourians, who were the house band at the Cotton Club before the Ellington band, had been in the wilderness for a bit. But to get out of this wilderness, they toured the Midwest and really tightened their act up as a band. So you have to imagine that they arrived in New York with a point to prove – that they could get back to the level where they were worthy of being the house band at somewhere like the Cotton Club.

Cab was leading the Alabamians, who had actually not been very good, and he knew the minute they went on tour from Chicago that he was leading a band that sounded old-fashioned to the listeners of the east. It is interesting that Cab had already recognized that, despite putting a lot of effort into leading the Alabamians, he didn’t consider them to be a long term band to lead, but, he did see them as a vehicle to use in order to leave Chicago.

He liked the way the Missourians played together as a band, and how they had a cohesive sense of swing without sounding old-fashioned like the Alabamians – who I suspect had a two-beat Ragtime sort of feel. Instead, the Missourians played a driving, full to the bar bluesy sound which gets Gunther Schuller terribly excited in his book, The Swing Era, where he called them one of the most exciting blues-based bands of the Midwest, and I believe he is right. Cab spotted that as well, and since the Missourians won the band contest and he won the leader contest, it was a natural conclusion that they’d put the two of them together.

JJM So he became the conductor of the Missourians…

AS That’s right.

JJM And he eventually became the M.C. of the Cotton Club…

AS Well it took a while. In so many stories it seems these kinds of things happen almost instantly – that the band wins the battle he wins the director contest, they get put together, and “Bingo!” they’re in the Cotton Club. But it actually took nine months for that to happen, not least because in those days if you came from an out-of-town musician’s union – and of course Cab was a member of the Chicago branch of the musician’s union, and the Missourians were members of the Kansas City branch – if you wanted to play in New York you had to deposit your union card and you couldn’t work regularly for six months. So in fact the band had to scuffle to find jobs out of town, or they played one or two nights a week with other people just in order to survive so they could come together and be adopted by the proper local AFM branch in New York.

Since Cab went out on the road as a variety artist during this time, it didn’t really affect him so much. He was in Hot Chocolates as a singer and actor, and singers and actors were immune to this restriction imposed on musicians. So he could appear on stage as a singer without compromising the deposit of his card with the musician’s union, which is one of those strange inter-union agreements that still mystify us today. But it meant that he couldn’t really get to leading that band full time until roughly May of the following year, and then it was a very quick progression from May 1930 to the beginning of 1931 when then band opens at the Cotton Club once Ellington goes out on the road.

JJM The Cotton Club audience loved Cab and his antics for who he was, irrespective of his skin color. What was his secret to winning over a crowd?

AS Well, two things. First of all, we have to remember that the Cotton Club audience was predominantly white. The only black members of the audience were celebrities – Joe Louis and, later on, Bojangles Robinson would have a table, but they were few and far between. In fact, the club actively discouraged African American patrons; they had a very unpleasant set of bouncers who were there to make sure that only the people they wanted came into the club. So Cab played to a white audience at the Cotton Club.

The other thing is that he was playing to a national audience every night on radio, and these half hour broadcasts from the Cotton Club, which had been very successful for Ellington, were even more successful for Calloway. Frankly, if you turned on your radio and heard somebody singing about Minnie the Moocher, your first thought isn’t whether the singer is black or white, it is that this is a good song. Cab had a complete ability to connect to any listener who heard him on the radio from the Cotton Club, and as a result he stacked up an enormous audience.

When the band went on tour in the south, audiences who felt they ought not to like them because they were a black band nevertheless turned up, and this was because they loved Cab. So he broke the color barrier in a very active way at a time when that wasn’t something many African American artists were capable of doing.

JJM It is interesting that much of his popularity came about as a result of his visual appeal, but this was the era of the radio…

AS That’s right, and, of course it helped enormously that he was very early into the film business, performing in everything from those Betty Boop films, which started being made in 1932, right through to things like the Big Broadcast of 1932 and then Cab Calloway’s Hi-De-Ho and other short features. So, it was very possible to see him performing. I think Terry Teachout makes a point in his rather excellent review of the book for Commentary magazine that the miracle of YouTube gives us a little insight into the way that he would have been seen by his public in the 1930’s. In other words, what we can click on a computer and see instantly people were going to the cinema to see, where they would have a chance to see Cab actually dancing.

I’m sure people talked about it. I’m sure the buzz was all about his stage antics, which includes a wonderful story told by bassist Gene Ramey about him winning a battle of bands by leaping on stage and somersaulting over chairs while singing at the same time. You can’t help but wonder how anybody could be physically fit enough and athletic enough to do that, but apparently he did. There is a particularly wonderful moment of him on camera showing his band in a Pullman car, crossing America, where Cab rehearses the band while dancing between the bunks in the sleeping car. He had almost no space to dance, yet he does this incredibly athletic routine, spinning around, shimmying, waving his hands in the air, directing with his baton, and the musicians are playing cramped up sideways in their berths with their instruments poking out from between the curtains. It’s remarkable! You realize that this was somebody who didn’t need a vast stage to perform. He could perform anywhere and still be absolutely the center of attention. But you’re right; it’s a paradox that somebody so visually exciting made his real impact nationally through radio.

JJM Well, his aural hooks were pretty compelling and he became popular even without the benefit of any kind of visual evidence of his show.

AS I think that’s true. Also, if you listen to the broadcasts from the 1940’s, you realize that some of his real tour de forces of verbal dexterity were things that he did night after night – they weren’t just an accident. He could get his tongue around the most extraordinary lyrics, but a lot of hard work and practice went into that to make it look so nonchalant. It’s only when you listen to the radio air shots over a period of months that you realize that the same song would pop out every three or four weeks, and it would be delivered with exactly the same verve and elan, irrespective of whether it was May or June or September.

JJM Calloway’s manager Irving Mills had great instincts about how to market Cab Calloway…

AS Yes…In the case of both Cab and Duke Ellington, Mills was indispensable until he became dispensable. Neither of them could have achieved the extraordinary elevator to stardom that they got on without him, and in Cab’s case, he kept him there for 13 years. One of the reasons that Cab didn’t split from Mills’ management when Ellington did at the beginning of the 1940’s is that Mills told him he would get him into the movies, and he did. It was only once, but nevertheless it was in that extraordinary sequence in Stormy Weather with the Nicholas Brothers jumping and leaping all over everything. It’s a remarkable tour de force, and we have to be grateful for Irving Mills for staying the course and making sure that Cab got into the movie, because it is a great moment. But even then Mills’ inexhaustible energy for promoting Cab began to lag.

By 1943, it became obvious that the partnership wasn’t going to last much longer. It took another 18 months or so before they broke up, but he was still able to do things for Cab. One of the things that I found quite remarkable in the Cab Calloway Papers in Boston University Library were examples of the meticulous press packs on Cab that Mills sent out. These packs included press releases for the local papers, advertisement, pictures that would support the copy, and photographs of recent events – all in order to support the appearance of the band.

This was a military operation in terms of its scope, and in the way it controlled lazy editors, basically, because without being unfair to the editors at the Pittsburgh Courier or the Chicago Defender or the Baltimore African American, if somebody provided them with ready-made copy and photographs and advertisements that all tied in, they used them. They weren’t going to change them, they just took what they got. Mills realized much earlier than other managers exactly how to manipulate the press to get maximum effect. I’ve been talking lately to Harvey Cohen, who wrote this extraordinary book called Duke Ellington’s America, and he said Mills worked with Ellington just as meticulously.

Of course, Mills made shed loads of money out of it himself, but he saw to it that they were making a very respectable living for themselves as well. It wasn’t until Ellington discovered that there was a considerable shortfall in his royalties that he finally peeled off, and with Cab it was when the bookings started to dry up.

JJM Mills called the press kit you refer to “His Hi-De Highness of Ho-De-Ho.”

AS It’s amazing, and it’s beautifully done.

JJM Yes, and it became a template for marketing artists…

AS I think it’s exactly the devices that people use now. If you’re marketing everybody from Beyonce to whomever, you’ll use the same sort of devices. I got quite involved in finding out about Irving Mills while writing about the subject of my previous book, the songwriter Jimmy McHugh, who was actually a partner in Mills’ Music with Irving and his brother, Jack. The first show Calloway played at the Cotton Club had a lot of Dorothy Fields and Jimmy McHugh songs in it. It is my contention that he actually did a lot to teach Irving Mills how to market the acts that he signed to his agency, because McHugh was a born salesman, and if not for being a brilliant songwriter, he could have certainly succeeded in sales. He was a remarkable character.

Many of the devices that we find Irving Mills using by the time Cab Calloway came along were things that Jimmy McHugh had rehearsed with him in the early 1920’s, when they were working with white bands like Paul Whiteman and Ben Pollack.

JJM How did Cab perpetuate the stereotypes of African Americans of the era?

AS Well, he sort of perpetuated and moved them on at the same time. A good example of that is the Hepster’s Dictionary. The irony of every dictionary is that it crystallizes usage at a particular point in time – the minute you write down words and say what they mean, it’s yesterday’s news, and that has been a problem for lexicographers since Dr. Johnson onwards. So while doing the Hepster’s Dictionary was supposed to make him seem hip and happening, it actually only preserved these stereotypical linguistic devices that made him sound dated almost immediately because it froze the language at that particular moment in time, but the language moved on. Even the second and third edition of that dictionary didn’t really change the fundamental definitions of most of the words. So I suppose you could argue that he perpetuated a series of stereotypes by the very unusual device of writing down the language and trying to preserve it. We think there were visual ones as well and there are other mannerisms in the songs, but I think that linguistic one is probably the most significant.

JJM The Hepster’s Dictionary was released around the same time that Benny Goodman was becoming popular…

AS The writer Damon Runyon, who obviously didn’t like Cab very much, made an interesting comparison between the young, respectable and earnest Goodman and the previous inhabitant of the kingdom of swing, Cab Calloway. So you can see that Irving Mills was definitely casting around for something that would preserve Cab in that preeminent position. The Hepster’s Dictionary was one of the tricks they used to try and make him seem “more hep” than Benny Goodman was, and it certainly succeeded with some of the public. But the dictionary was definitely brought to market as part of a very calculated campaign to try and compete with the likes of Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw and Tommy Dorsey.

JJM It is especially interesting since Cab appealed to both the black and white audience, and the dictionary was seen as an attempt to try to hang on to the white listener…

AS Yes, and he partly lost that during the big band period, and certainly as the war began. He definitely felt that to some degree he was losing ground, which was one of the reasons why in the mid-1940’s he played long residences at the Club Zanzibar, a night life destination just off of Times Square. He became something of a home-based institution there, playing there for three month seasons, which was really unusual for the time.

JJM You report in the book that he made $275,000 during one eight-week run there, which broke all New York nightclub records for the time.

AS Yes, a very successful run. Fortunately we can actually hear some of that because some of those performances were broadcast and it’s a very, very slick show.

JJM There was a sense among critics that his band was almost a novelty band. Of the instrumental recording “Moon Glow,” you wrote, “Despite the casual nature of the recording of ‘Moon Glow,’ the piece came at a time when on record date after record date Calloway’s band was demonstrating that it was in the first rank of swing orchestras.” Is this a widely held opinion?

AS No, I don’t think it is, but while I do think it’s one that is growing, it is also one that some people vehemently disagree with. If you talk to Loren Schoenberg, who annotated the mosaic box set Chu Berry’s recordings, he feels that the Calloway band was very definitely second rate. I’ve had long, late-into-the-night conversations with Loren about it and we just agree to differ on this. But what I hear is a band that systematically improved its rhythm section, one that gradually brought in guitar and banjo, and one that changed the role of the piano and drummer so that the evolution of the music is reflected constantly in the way that the band changes.

What you don’t hear in Ellington, Basie or Lunceford is those bands reacting to fashion in the same way that Cab did – they tended to be fairly constant. Although the Basie rhythm section didn’t arrive on the scene until a bit later, that Freddie Green, Joe Jones, Walter Page setup doesn’t change materially for ten years – it’s not until the end of the 1940’s before it changes into a different sort of band – whereas Cab’s rhythm section reflects fashion all the way through. Leroy Maxey and Jimmy Strong are not the same as Cozy Cole and Milt Hinton – theirs is a different sound, and that’s true of all the sections of the band.

So Loren, on the other hand, tends to look at the novelty song, of which there were many, of course. But there’s plenty of jazz material in there as well, including lots of wonderful arrangements by Buster Harding and some of the other great writers of the period. It’s easy to lose sight of those and to see just the novelty numbers, the paradox being that those novelty numbers went over very well with the audience.

JJM Cab Calloway’s band was host to some of the great musicians of the era – Ben Webster, Cozy Cole, Dizzy Gillespie, Ike Quebec, and Chu Berry among them. You describe Berry as being a catalyst for change in the band.

AS Well, that is very much the view of all the guys I spoke to who were in the band at the time. The feeling was that since he had been recommended to Cab by Ben Webster, who was his friend and drinking buddy, and because he was so respected as a soloist, he got a degree of respect from Cab that ordinary rank and file members of the band didn’t. While Ben used this respect to have a great time at Cab’s expense, Chu Berry used it to improve the musical opportunities for himself and the entire band. Until Chu Berry’s arrival, there were just a handful of instrumental-only recordings by the band, but after Chu joined, the band recorded many more instrumentals. As I said in the book, it’s a little bit like Louis Armstrong handing over his band and saying, “We’re going to do a number without a trumpet solo and without a vocal,” and it would be inconceivable that Duke Ellington would record a piece without a piano.

Yet Cab, quite regularly, records pieces on which he doesn’t appear, like “Lonesome Nights,” “Ghost of a Chance,” “The Lone Ranger,” and a whole slew of them. So, once Chu arrived, Cab realized that the band was so good that it should be promoted in its own right.

JJM Yet he had trouble advocating for Dizzy Gillespie, musically…

AS Yes, and I think I have revised my view on this since I wrote the Dizzy biography. It’s interesting that when you write a biography about someone, you tend to become an advocate for that person. So I was really rooting for Dizzy at the time I wrote his biography, and I felt he was unfairly treated by Cab, especially thinking that he should have had more solos. He certainly should have been commissioned to write more arrangements because the two he did write are really good.

So I felt at the time that Dizzy was badly done by, but after having talked to more of the musicians since, and having read a lot more about it, I think he must have been a very difficult guy to have in the band. He was a very ambitious, very funny, very charismatic figure who didn’t want to play it by the rules, while Cab was an autocratic band leader who expected people to play it by the rules. This time around, while writing about Cab, I was his advocate, and I could see that Dizzy was perhaps more of an irritant then I was prepared to accept when I was writing about Dizzy.

JJM Concerning how Cab treated the musicians in his band, Garvin Bushell said Cab “…was a little rougher than he should have been on musicians. On the stand he was a tyrant. He ran his orchestra with an iron hand, not giving much room for your decisions, your concept.” We know so much about Dizzy now, but, turn the clock back to when he was a young man…

AS As I wrote in my Dizzy biography, I think he learned a hell a lot about how to run a band from watching Cab. He may have been the thorn in Cab’s flesh, but when it came to running his own orchestra, you see a lot of things that he picked up from Cab, exercising themselves in Dizzy’s own practice. This may not be so true of his 1946 – 1949 big band, but Benny Golson, Benny Bailey, Ray Brown and others in Dizzy’s band I have talked to say that he very much became the kind of tyrant on the bandstand that Cab had been. He might have looked wonderfully relaxed and happy to the public – and so did Cab – but he was a pretty stern band leader.

JJM So many of Cab’s songs satirized religion and drugs, but he had very little patience for musicians with drug problems.

AS That’s right, he had no patience at all for them, and I think he would have been horrified if he realized how severe Ike Quebec’s addition was, for example, although even the trumpeter Jonah Jones – who was on the bandstand with him – didn’t realize how bad the problem was until later. Milt Hinton noticed him dozing off but had no idea that it was the result of addiction until after Quebec had left the band. So there is some evidence that addicts concealed their behavior from those around them, and that certainly worked on Cab.

JJM What role did he imagine for himself after breaking up his band in 1947?

AS Well, I think he became somewhat lost at this point. I went through some of his papers in Boston where he was sketching out the possibilities of selling a “Cab Calloway’s Cotton Club Review” concept to television, but, while he understood cinema and could connect to that audience since the gestures he used on stage transferred pretty effectively to cinema, those same gestures on television made him look like an overacting, manic character who waved his arms like a windmill.

I think Cab took a long time, probably not until many years later, before he realized the subtleties of television and how it worked. While I know this is a role in cinema, when you see Cab appearing as Curtis in The Blues Brothers, you actually see in his acting how he learned to scale down his performance to make it look more natural. While he plays the role of the janitor, talking to the characters Dan Akroyd and John Belushi, you see him playing it down with minimal movement and minimal overstatement. Of course, when he goes on stage and sings “Minnie the Moocher” that’s a different story. But in that film, you can see that finally, during the 1980’s, that he understood how to act naturally on screen, whereas when he broke up the band in 1947, he had a giant bandleader persona that didn’t fit into the way entertainment was moving at the time. So I think he had a rough time, and things were really tough on him until he was picked to star in Porgy and Bess about five years later.

JJM It was a tough time for him since he had gambling debts and financial commitments to his ex-wife, and no way of making the kind of money he needed. When the Porgy and Bess opportunity came along, did he have a sense that there were substantial commercial rewards, or do you think he just looked at it as something to do?

AS I think he was terrified. He was worried about breaking up his quartet, and his wife Nuffie said he didn’t know if the Porgy and Bess role would work or not. Since there was no going back to the quartet, he was committed to the show, and if that didn’t work, he was going to have to find work with no efficient agency working on his behalf. So there was a measure of worry about this, but the great thing is that the minute he got the role, it fit him like a glove. It’s no accident that Gershwin said the role of Sportin’ Life was at least partly inspired by Calloway himself.

JJM What was his public image at the time of this on-stage role?

AS It’s interesting, it was rather like seeing somebody who was a rock star of 20 years ago suddenly reinventing themselves as a stage actor. Not many have done that successfully – maybe David Bowie is an example of someone who, when he performs credibly as a film actor you think, “Wow, he can act as well.” To some extent, I think this is Cab in the 1950’s appealing to an audience who would have heard him “Hi-De-Hoe-ing” in the 1930’s and 1940’s. He was put into a different role and resurrected.

The great thing that happened for him in that show was that he was able to work fit in little bits of his cantonal, hi-di-ho singing on “It Ain’t Necessarily So,” and he realized he was able to be the Cab Calloway people knew and loved, but in the character of Sportin’ Life. It was an ideal part for him to take because his old public liked it and his new public thought, “Wow, this man’s extraordinary and we’d never have known.”

JJM You spent a lot of time with Cab Calloway during the process of writing this book. Is there anything that surprised you about his life or how people have responded to your recording of it?

AS One thing I find interesting is that there is still critical resistance to seeing Cab in terms of the body of work that actually exists as opposed to seeing that body of work through the prism of all the critics who looked at him before. In other words, a lot of people continue to see him as a novelty act who held back a very good band. There have been two or three people who have reviewed the book who’ve said that I tried to make a case for Calloway but that I didn’t really succeed, that Calloway was a novelty singer, and that it is a pity that you can’t hear more of Chu Berry, Jonah Jones, or the others in the band.

On the other side of it, there have been some who caught on to what I was trying to do, which is to see Calloway as a very pivotal figure in the development of the entertainment industry, and someone who was in the right place at the right time for everything from entertainment marketing, to the dawn of radio, to the exponential growth of recordings after the depression, to becoming a stage actor and then a film star. I suspect that as time goes on, it may become more apparent to readers that the message of the book is that Cab Calloway was someone who was able to use the emerging mass media of the 20th Century to become a larger-than-life personality – and he created a career out of being just that.

.

photo by William Gottlieb/Library of Congress

“My audience was my life. What I did and how I did it, was all for my audience.”

– Cab Calloway

.

___

.

Hi-De-Ho: The Life of Cab Calloway

Hi-De-Ho: The Life of Cab Calloway

by

Alyn Shipton

.

.

About Alyn Shipton

Alyn Shipton is the author of several award-winning books on music, including A New History of Jazz and Groovin’ High: The Life of Dizzy Gillespie. He is jazz critic for The Times in London and has presented jazz programs on BBC radio since 1989. He is also an accomplished double bassist and has played with many traditional and mainstream jazz bands.

.

____

.

.

JJM Who was your childhood hero?

RK I have two childhood heroes. My real childhood hero when I was about five years old was Admiral Lord Nelson. I remember that my mother actually ended up making me a sailor’s costume and a hat, which was very difficult because Nelson lost his arm at the Battle of the Nile, so the jacket only had one arm and I had to pin mine down inside. But I was so fanatical about this great sailor that I wanted to be him when I was about five or six years old. So he was my first great hero, and it all came from a book that my grandmother gave me, which is a Victorian book called The Little Book of Heroes. I think it over-egged the pudding about what a hero he was, but I certainly believed it when I was a very small boy. So that’s my first one.

My second one, which was my first musical hero, was Fats Waller. That’s because when my father came back from the war – he served with the RAF in Hong Kong – he brought with him a huge collection of 78 rpm gramophone records. I have no idea how they survived the voyage, but they did. Mainly they were Duke Ellington, Earl Hines, and Fats Waller, and that’s what I was played when I was a little child to keep me quiet. They used to put on stacks of 78’s on one of those things where the records would drop one after another and just play, almost like the precursor of the bands of an LP, and so I’d hear five or six Fats Waller tunes in a row. Now, of course, at that stage, being very small, I listened to the words and the funny lyrics, and I wasn’t really taking much notice of the music, but I suspect it must have crept in.

.

.

Critical Acclaim for Hi-De-Ho: The Life of Cab Calloway

“I met Cab Calloway at Eddie Condon’s club — he lit up the room by his presence and I can understand why everyone loved the man. Alyn Shipton captures Cab’s spirit in his biography Hi-De-Ho; every page is filled with anecdotes about Cab and his music. Chu Berry, Ben Webster, and other well known musicians spring from the pages. Not only does Shipton bring Cab Calloway to life, he makes the reader understand the era in which he lived. For a short time, we enter his world, and what a world it was.”

– Marian McPartland OBE, jazz pianist, writer, composer, radio host (Marian McPartland’s Piano Jazz)

.

___

.

“Makes a solid case for Calloway as a jazz musician as well as an entertainer, and he certainly makes you want to listen to “Minnie” and all the others, for the umpteenth time in my case and, it is to be hoped, for the first time in others’.”

-The Washington Post

.

___

.

“Shipton gives [Calloway] his due. Must reading for swing buffs.”

-Terry Teachout

.

___

.

“Provides a reliable, fully informed account of Calloway’s career, one in which the emphasis is placed squarely – and properly – on his musical achievements…I can think of no better way to be brought face to face with the extent of that achievement than to read Hi-De-Ho.”

-Commentary

.

___

.

This interview took place on April 6, 2011, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita

.

.

If you enjoyed this interview, you may want to read our interview with Fletcher Henderson biographer Jeffrey Magee

.

___

.

# Text from publisher.

.

.

___

.

.

Click here for other Jerry Jazz Musician interviews

Click here to read The Sunday Poem

Click here to read “A Collection of Jazz Poetry – Summer, 2023 Edition”

Click here for information about how to submit your poetry or short fiction

Click here to subscribe to the (free) Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter

Click here to help support the ongoing publication of Jerry Jazz Musician, and to keep it commercial-free (thank you!)

.

___

.

.

Jerry Jazz Musician…human produced (and AI-free) since 1999

.

.

.