.

.

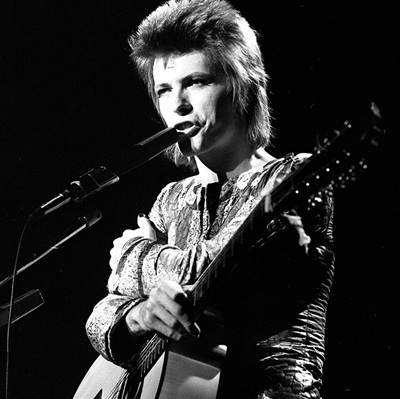

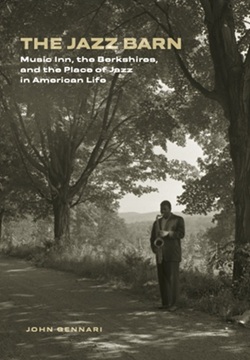

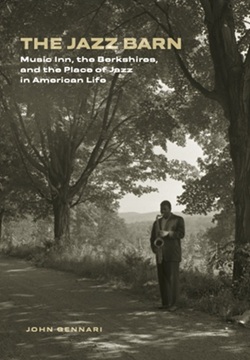

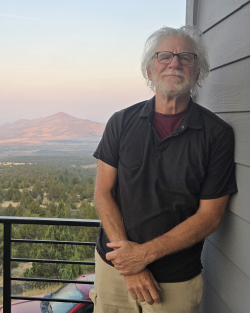

John Gennari, author of The Jazz Barn: Music Inn, the Berkshires, and the Place of Jazz in American Life [Brandeis University Press]

.

.

__________

.

.

Dear Readers:

…..Jazz has always been an urban music. Born on the streets of New Orleans, it moved upriver into the clubs of Kansas City, St. Louis, Chicago, and New York, where it flourished in neighborhoods and in grand ballrooms and concert halls. It also thrived in inner-city Washington, Baltimore, Detroit, Philadelphia, Boston, Pittsburgh, San Francisco and Los Angeles, and was mostly performed and made famous by men and women who grew up in urban environments.

…..An exception to this scenario was the vision of Philip and Stephanie Barber, a New York City couple who, after buying an estate in the bucolic landscape of the Berkshires in western Massachusetts, turned its “Jazz Barn” into a performance venue, as well as utilizing their property as a place for workshops and educational activities whose goal was to get away from the urban centers to develop a deeper understanding of American vernacular music, especially jazz. It attracted major recording artists and music scholars of the time – Duke Ellington, Dave Brubeck, Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie, John Lewis, Ornette Coleman, Leonard Bernstein, Nat Hentoff, and Marshall Stearns among them – who gathered to perform in a pristine setting, as well as to participate in roundtables grounded in folkloric approaches to the music.

…..The assemblage of these now legendary artists in the Berkshires, writes John Gennari, author of The Jazz Barn: Music Inn, the Berkshires, and the Place of Jazz in American Life, meant that it was now not just “an important incubator of American literature and classical music, but also [for example] of the Modern Jazz Quartet and Ornette Coleman’s ‘new thing.’”

…..Gennari takes on this fascinating topic of a place’s influence on musicians and music with the same verve and skill he did in his 2006 book, Blowin’ Hot and Cool: Jazz and its Critics, which remains the definitive history of jazz criticism. That book explores the relationship between the writers, producers, and intellectuals with the musicians whose work shaped much of what America listened to during jazz music’s golden era.

…..In The Jazz Barn, he expertly writes of the complexity of race, culture, and place, and how the Berkshires – home to the likes of Hawthorne, Melville, Wharton, Rockwell, and Tanglewood – became a crucial space for the mainstreaming of jazz, and eventually an epicenter of the genre’s avant-garde.

…..Gennari talks with me about his marvelous book in this November 25, 2025 interview.

Joe Maita

Editor/Publisher

.

.

__________

.

.

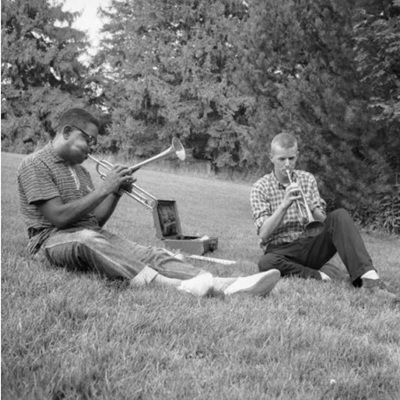

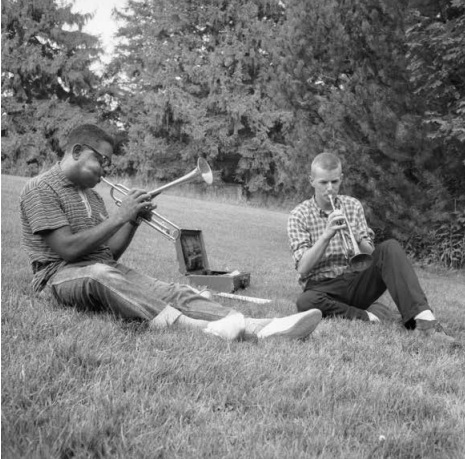

photograph by Warren Fowler/used by permission of author

Dizzy Gillespie and a student on the Music Inn lawn, 1957

.

What did it mean for ragtime and early jazz pianist Eubie Blake to conduct a lecture-demonstration in an estate carriage house in the Berkshires? For vocalists Mahalia Jackson, Anita O’Day, and Billie Holiday to sing from the stage of an indoor-outdoor concert venue fashioned from a former hay barn? For fellow musicians to listen to those singers in that setting? For Dizzy Gillespie to conduct jazz harmony classes on the lawn outside of that barn? For Jimmy Giuffre, a swingband veteran then crafting a new style of improvisational chamber jazz, to jam with his student Ornette Coleman, herald of the free jazz avant-garde, in a makeshift nightclub remodeled from what had been a greenhouse? For Berkshire locals and out-of-town vacationers to see and hear Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and Thelonious Monk after driving backcountry roads, leaving their cars in a makeshift grass parking lot, and walking a tree-lined path up to the concert site?

Only rarely can historical sources help us satisfyingly capture the full multi-sensorial dimensions of such richly textured experiences. But simply to ask these questions is to intensify our thinking about music as an affective, physiological, social, and interpersonal experience. “If hearing is a major component of our sense of emplacement in the world,” the musicologist Andrew Berish reasons, “then music, a particular, culturally determined manifestation of sound, must also contribute to a sense of place, a feeling in the listener of being meaningfully located.” In this sense, music “sensuously produces place.” And place—physical location combined with the psychologically potent meanings imaginatively attached to it—produces music.

-John Gennari

.

.

Listen to the 1956 recording of the Modern Jazz Quartet playing the John Lewis composition “A Fugue for Music Inn,” with Lewis (piano); Milt Jackson (vibraphone); Percy Heath (bass); Connie Kay (drums); and Jimmy Giuffre (clarinet). [Rhino/Atlantic]

.

___

.

JJM In the introduction to the book, you wrote; “This is a book about what happened in the 1950s in a barn, icehouse, and greenhouse and in the rolling meadows, winding wooded paths, and rocky brook edges of an estate property overlooking a lake in the verdant Berkshire Hills of western Massachusetts. What happened in this place unsettled conventional assumptions about the relationship between culture and landscape, art and geography, town and city, race and place. What happened there, against all odds, was a set of developments crucial to the history of jazz.” You have been wanting to write this story for a long time. Who started Music Inn and what was their original mission for it?

JG Music Inn was started in 1950 by a New York couple, Philip and Stephanie Barber. Philip came from the theater world, having been for a time in the 1930s the director of the Federal Theater Project, one of the WPA arts programs in the New Deal. He grew up in Iowa and moved east for college at Harvard, eventually becoming a founding faculty member of the Yale School of Drama, where he taught for six years. He later started a public relations firm, where he hired Stephanie Frey, a New York girl who grew up in Queens, and who had become a fashion journalist. At the firm, she worked on the stateside marketing campaign for the French fashion designer Christian Dior’s new clothing line, which received a lot of attention in the fashion world.

They married in the late 1940s – he was 16 years older and had two children from his previous marriage. As a couple they were friendly with writers and musicians like Langston Hughes and Alan Lomax who helped shape the Inn’s early programming of artists like the folk musicians Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie. The Barbers had been coming up from New York to attend theatre productions and concerts at Tanglewood, which was the summer home of the Boston Symphony Orchestra and just around the corner from the estate. The Berkshires was becoming an important site of summer performing arts between Tanglewood, the Berkshire Theater Festival, the Williamstown Theater Festival, and others. They liked the Berkshires so much they decided they would like to create something for themselves there. So they bought a set of outbuildings and 100 acres of a Gilded Age estate in the Berkshires on the border between Lenox and Stockbridge, Massachusetts.

The property was sold to them by the Boston Symphony Orchestra, which was using the estate for its summer music conservatory. The concept of Music Inn emerged from conversations among their friends who were keen on the idea of having a place that would provide a venue for performance but also potentially workshops and other kinds of educational activity that could result in a better public understanding of American vernacular music – jazz, folk, blues, etc.

Pete Seeger (left) and Woody Guthrie (right) performing at Music Inn’s first

concert, July 2, 1950. Dan Burley sits to Seeger’s right, Reverend Gary Davis to

Guthrie’s left. Photograph by Leonard Rosenberg/used by permission of author

The other thing I’ll mention is that when Philip was the Federal Theater Project director, much of his interest was centered at the Lafayette Theater in Harlem, where he presided over a whole slew of productions. The theater employed hundreds of African Americans, and it began an outreach effort to Harlem public schools for the purpose of introducing the children to drama and the theater. This was during the Depression era, so many of the productions had a leftist tilt. Martin Dies, the influential chairperson of the very first House Un-American Activities Committee, caught wind of this, and became convinced that the very concept of racial equality was a communist notion, one that was anti-American at its core. This resulted in the pulling of federal funding for the theater. I mention this because many of the performers and people hanging out at Music Inn starting in the early 1950s, when the inn opened, had been blacklisted – people like Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie and Alan Lomax and some others.

The Barbers were not going out of their way to advertise themselves as leftist radicals, or to market Music Inn as a place of refuge from the blacklist, but that’s what they were quietly doing. So, it indeed became an important place for people like Seeger, who many years later wrote a letter to Stephanie that specified just how crucial she was to his career when he was able to perform at Music Inn and some other places around the Berkshires while he was blacklisted.

JJM There are many interesting parts of the story that you tell, and “race” and “place” is of particular interest to me. The setting in the Berkshires was so different from the smoky night club atmosphere in which jazz musicians of the era were accustomed to playing. Music Inn had to have impacted the way jazz was composed, played and recorded, and the way in which Black and white musicians came together to study and perform. Can you talk a little about the importance of race and place within the Inn’s mission?

JG I will start by answering about place. The Berkshires was an arts and culture destination going back to the 1930s, with institutions like Tanglewood, the theater festivals, and Jacobs Pillow Dance Festival based there. This expanded further during the post-World War II era, with the advent of a middle-class cultural tourism industry feeding off the general economic upturn. The Berkshires has a long history of important real and symbolic resonance in the American story. It was a place where writers gravitated in the 19th and early 20th century – authors like Herman Melville, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Edith Wharton come immediately to mind. Melville’s Moby Dick was written while he was living in Pittsfield and Hawthorne in Lenox. There is a famous story about a hike they took up Monument Mountain, just south of Stockbridge in Great Barrington, and the day turned stormy, causing them to take refuge in a cave, where they had a transformative discussion about American literature. Melville was so moved by this conversation that he dedicated Moby Dick to Hawthorne. Later, Edith Wharton bought property in Lenox and built an estate there called The Mount, which is where she created much of her nonfiction writing about home design and interior decoration. And her novel, Ethan Frome is set in Lenox. So the social lives of the well-to-do bears the imprint of that place.

Much of the important history of the area has to do with its location in the western part of Massachusetts, where the farming communities during the colonial era played a big role in the vision of how the nation would be governed. The famous event known as Shays’s Rebellion was a southern Berkshire County farmers’ uprising against the Commonwealth over taxation, and demonstrated the power of populism. Historians view this as the completion of the American Revolution.

Later, the area became tightly connected with the mills and factories located along the Housatonic River. For example, electricity was invented in the area. General Electric opened a plant in Pittsfield in 1912; by the 1950s it employed close to 15,000 people, including my father, who worked as a welder on power transformers. (When G.E. pulled pulled out in the 1980s, it devastated the city). Simultaneous to it being an industrial center, during the American Renaissance of the mid-19th century the area had a connection to the arts and intellectual life that included people like Melville and Hawthorne and Emerson and others who were also deeply committed to the abolition of slavery. So, these two forces – industrialization and the humanities, the engine and soul of the nation – came together in this one place. It was also a place of great natural beauty, so it became a place of recreation and relaxation, where quasi-religious, spiritual ideas about the importance of nature to humankind take shape. So, the Berkshires is a place that is touching on all these important nodes of the emerging American nation and its narrative.

None of this has anything to do with jazz and non-white people, other than the displaced natives of the area, the Mohicans. There were only a small number of African Americans who settled in Pittsfield and Great Barrington and North Adams, because during the Great Migration of the early 20th century there was not a lot of industry in the region, and those jobs were elsewhere. On the other hand, there are famous and historically crucial African Americans who are connected to the Berkshires, most famously W.E.B. DuBois, the premier Black intellectual of the 20th century, who was born and raised in Great Barrington. James Weldon Johnson, the novelist, poet and songwriter who like Dubois was a central figure in the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s, had a cabin in Great Barrington that he used as a writing retreat. And James Van Der Zee, who became a hugely important figure in Harlem as a photographer during from the 1920s to the 1960s, was born in Lenox and was one of the first people to visually document local Berkshire town life. He was also a classical musician who moved to Harlem, in part, to be part of a classical chamber orchestra.

And the area also had people like my father and others who were what we would call at the time “white ethnics” – Italians, Poles, Eastern and Southern Europeans who came to work at places like General Electric and the paper mills along the Housatonic River. So, there was a large diverse white population and a not quite as diverse and much smaller Black population that is made up of a highly disproportionate number of elite people connected to the arts and intellectual life.

JJM This was an environment that wasn’t necessarily available to the inner-city Black community, nor to its musicians. How did the setting of the Berkshires that you laid out impact their creativity and the music that came from it?

JG Jazz is about movement and mobility. I write in the book about its connection to travel, and the sound of the railroad that is heard in lots of jazz music and in other kinds of Black music. And this is important because, after all, what were slavery and Jim Crow segregation if not an effort just to keep Black people in their place? So, freedom for Black people had a lot to do with the freedom to travel, and to move. And when jazz becomes such an important cultural force all over the world, the musicians got to travel much more widely than most Black Americans did – all while dressing well and carrying themselves with dignity and poise – and become cultural heroes within the Black community.

Jazz is an urban music that traveled from New Orleans up the Mississippi to other cities like Kansas City, St. Louis, and Chicago, eventually converging in New York, where a culture for the music takes shape, first in Harlem and then increasingly within the famous cozy and smoke-filled clubs of Manhattan, where listeners could absorb the music and the charisma of the musicians. These clubs helped promote the importance of the visual component of jazz – photographers loved those small spaces and eventually shot what became canonical pictures.

But cities like New York became an increasingly problematic space for musicians, much of that having to do with the scourge of heroin. Many of the musicians became addicted and ran into trouble with the law, leading to the loss of their cabaret cards and an inability to perform in clubs that sold alcohol. On top of that, school systems were suffering as a result of white flight to the suburbs, and the tax base was shrinking, leaving many of the musicians in a tough place economically and culturally. They began looking beyond the urban neighborhood as the space for their life, and for their art. So, the Berkshires became an attractive space, and what was developing at Music Inn was almost like an upscale summer camp experience.

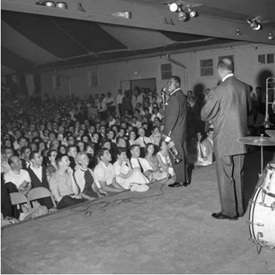

Photograph by Warren Fowler/used by permission of author

Louis Armstrong performing in the Music Barn, 1956.

.

Photograph by Carol Reiff/used by permission of author

A roundtable with Leonard Feather, Dizzy Gillespie, George Wein, Willis Conover, Teddy Charles, and others. 1956

For starters, the jazz historian and missionary Marshall Stearns began a series of jazz roundtables there in the early 1950s that eventually led directly to the advent of the Institute of Jazz Studies. In 1955, the Barbers converted the stables on their property into a performance space, launching the creation of a summer-long series of folk and jazz concerts. The Newport Jazz Festival had started the year before and continued throughout the 1950s, and there was a lot of overlap in the programming at the two venues, but the Newport festival lasted only one weekend. The Barbers’ Music Barn, on the other hand, was 10 or 12 weeks of summer concerts featuring headliners like Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, Louis Armstrong, Billie Holiday, and Ella Fitzgerald, inspiring many people to come to the small town of Lenox. So, the music is moving from a fast-paced urban environment to small town New England, with its mountains and lakes and walking paths, the kind of space that very much supports a 1950s narrative that jazz is becoming part of the American mainstream. The jazz of the period is even referred to as “mainstream” as a way to create some coherence out of the jazz tradition.

JJM This environment, as you say, offered Black musicians a much different environment in which to perform, and not all were comfortable in it. John Lee Hooker, for example, felt an early uneasiness there. What were some of the challenges Black musicians had with interacting with the space creatively?

JG Let me begin by saying that, despite some of the challenges I will discuss, they really embraced Music Inn as an important development. The idea that the building of a cultural and intellectual space for jazz – an infrastructure for jazz, ultimately including a school – was the ultimate sign that the music was being taken seriously and not being seen entirely as a subculture connected with houses of ill repute and the drug trade. So, it becomes a space of important refuge for them.

One of the challenges was that even though Lenox isn’t far from major population centers like New York, Boston, Albany and Hartford, not many Black people lived in the Berkshires, and those who did tended to be part of the service class working in the restaurants and hotels. There are stories about the musicians and the wives of musicians driving on roads that don’t look all that different from the back roads of Mississippi – where Black people and civil rights workers were being attacked or murdered or disappeared at the time – wondering if the same could happen along these roads. And while the Music Inn was a community of liberal integrationists, what about the surrounding area? Would they be welcome there? The fact is that Black people in general, not just the musicians, had difficulty securing lodging in Lenox and Stockbridge during this time. If it weren’t for the Barbers at Music Inn, the musicians would have had difficulty finding a hotel.

There aren’t a lot of stories from the Black musicians who were there at the time about overt racism, and I think that’s a tribute to the Barbers and the white musicians as well. While there were personal frictions, their mission included creating a model interracial community. The jazz world, like any other art world, had its experience with internal dissension, but Music Inn was largely seen as a kind of “utopia” within which to create.

People like John Lewis of the Modern Jazz Quartet, who becomes the artistic director of the Lenox School of Jazz, along with others like Randy Weston, Max Roach and Dizzy Gillespie embraced this as a summertime, off-the-road experience. But it’s really not, because when the school opens they’re teaching without being paid for it. They’re giving up the opportunity to tour and take concert dates but are so committed to what’s going on that they’re willing to work for free. They also like the idea of being able to spend time with their family in what to them feels like an elite resort.

JJM This was during a time when there was a general sense of tension among Black and white jazz musicians. Did Music Inn alleviate some of that?

JG I think it did. It wasn’t completely free of it, but it’s been hard to find evidence of legible friction. Some of the white musicians who came to Music Inn like Gerry Mulligan and Jimmy Giuffre were from the cool jazz scene of the west coast, which was largely white and which east coast-based Black musicians thought involved racialized marketing that took attention away from what people like Miles Davis and Sonny Rollins were creating. But Miles Davis hired Bill Evans to play for him, and Evans was a faculty member for a time in Lenox. There’s a story about Miles and his group being scheduled to play in Lenox the very week that Kind of Blue hits the market, but Miles cancels the show. Bill Evans had a reel-to-reel recording of the tunes, which he played for everyone at Music Inn in advance of the LP hitting the market, and that created tremendous excitement for it.

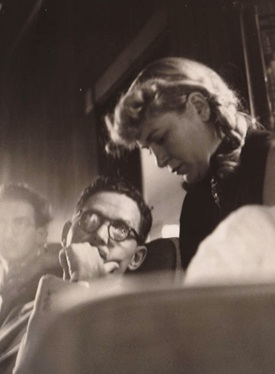

Photographer unknown/used by permission of author

Willie “The Lion” Smith and Miles Davis, watching the end-of-session jazz concert at Music Inn, 1956

I think that when the roundtable discussions began to be run by the musicians themselves in 1956, discussions like race relations were openly discussed in this quasi-academic setting. There were tensions, to be sure, and there were debates over a lot of other things that were not necessarily connected to race – issues like whether jazz needed to be an improvisational music with blues as a kind of undercarriage, and coming up with a definition for swing and jazz itself. The roundtables allowed them to speak with authority about their experience as musicians, and to express the kinds of artistic visions they had. So, this is such a different dynamic in the relations between musicians, even between musicians of the same race.

What the Barbers created at Music Inn presented the musicians with a much different kind of model of the managerial class compared to the club owners and the booking agents and the record companies so necessary for the musicians, but who were oftentimes resented. Nobody had anything bad to say about the Barbers, and in fact lifelong friendships develop and are sustained between them and the musicians. Music Inn signified a space so very different from a musicians’ normal day-to-day music industry interactions and experiences.

.

A musical interlude…Listen to the 1958 recording of Sonny Rollins and the John Lewis Trio playing Rollins’ composition “Doxy,” with Rollins (tenor saxophone); Lewis (piano); Percy Heath (bass); and Connie Kay (drums). [The Orchard]

.

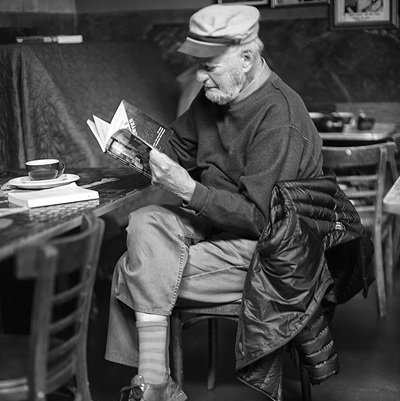

JJM A component of the book I especially enjoyed are the photographs taken of the property, and of those who participated on it. There are several different photographers, but one of special interest to me is Clemens Kalischer. His beautiful images include those of musicians lounging on the lawns of the property grounds and walking along tree-lined boulevards, and within the confines of the Inn itself. How did these photographs influence how people – and the jazz world at large – viewed the work being done at Music Inn?

JG As it happens, many of the photographs in my book were not seen until they were published within it, but those that were are important because they inspired a lot of coverage in the press. Many stories appeared in Downbeat and the jazz press, but also in the New York and Boston papers, and also in many Associated Press stories that were circulating nationally. This partly had to do with the fact that the Barbers were skilled in the art of publicity and knew how to get the right people’s attention. Some of the photos published at the time became very well-known. One was of John Lee Hooker, which first appeared in Record Changer, the very specialized jazz magazine of the 1950s.

Regarding Kalischer, I had originally imagined this book being just a study of him and of his photographs, and how he ended up in the Berkshires. He was a German-Jewish Holocaust survivor, a refugee from Hitler’s Germany. His family separates and he spends three years in several different labor camps in Vichy France. His family reunites miraculously, and they join up in New York.

Clemens had an interest in photography, but now he began thinking about making a career out of it. He takes a course with Berenice Abbott at the New School and falls in with the Photo League, which was an important collection of left-leaning photographers who documented the experiences of workers and racial minorities. He’s not so interested in the politics of the group as he is having access to the resources needed to create a photograph – the cameras, the film, the dark rooms. He ends up traveling north to the Berkshires to shoot some photographs at Jacob’s Pillow for a dance magazine, falls in love with the area, and moves to Lenox at the same time that the Music Inn launches.

He was staying in a cabin at an Inn just down the street from Music Inn and just happened upon it, not knowing what it was. He didn’t know anything about jazz and prefers classical music, but he sees that something quite important culturally and intellectually is taking place. So, what he ends up doing is photographing the scene, taking shots of famous people he doesn’t even know are famous; for example, he doesn’t know Dave Brubeck from the students working at the School of Jazz during that time. But he becomes very friendly with Ornette Coleman, Gunther Schuller and some others because he’s interested in culture and politics and is convivial. He has a documentary style of photography and creates his career around it. He is successful right away, getting his photographs published in the New York Times, Fortune, and other New York magazines. His work is represented at Edward Steichen’s “Family of Man” exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art and is most famous for a series of late 1940s photographs of Jewish refugees arriving in New York following the war. It became a series knows as “Displaced Persons” and received a lot of attention.

So, he’s got some cachet, but by moving out of New York and out of the Photo League, to a certain extent he marginalizes himself. He maintains connection with New York editors and sells a lot of photographs there, but he undertakes a career largely shooting scenes in New England, including the performing arts scenes. Music Inn was just a small part of his overall body of work during this period, but like some of the other Jewish refugees such as Francis Wolff – one of the founders of Blue Note records who was also a photographer – he was interested in using his skill as a photographer to connect jazz to American modernism. He shoots in black and white with great documentary clarity, catching people in moments of gesture and interaction that are very meaningful. Henri Cartier-Bresson was the famous European photographer of the time best known for that kind of photography; Kalischer connects with him later on, even taking photographs of him. So, Kalischer became a big figure in the photography world but was not a household name. His photos in my book represent just a part of his work. I’m hoping they will create an interest in his entire career.

JJM A big part of the story for me was how Marshall Stearns and the roundtable attempted to come up with a bulletproof definition for jazz. This took place among many differing personalities and viewpoints. It had to have been fascinating…Who was involved in this, and how did they ultimately define jazz?

©Stephanie Barber Collection/used by permission of the author

Marshall Stearns (left), with Stephanie Barber; 1952

JG Stearns had been writing jazz criticism since he was a graduate student at Yale in the 1930s, and he appears in Downbeat fairly early, around the same time as John Hammond, who he’s pretty close with. The two of them were probably the two most important people in terms of prosecuting the argument that jazz is a Black music that comes out of Black community life. That isn’t to say that white musicians can’t play the music or don’t belong near the music – quite the contrary. But their argument needed to be made in the late 1930s because at the time jazz was still associated with Paul Whiteman and his project of orchestrating the music for concert hall performances played by “trained” (i.e. white) musicians.

Stearns was an academic whose scholarship was unconnected to any of this. He was a Chaucerian, a professor of medieval English. He has a series of teaching jobs, losing one at Indiana University during the Red Scare because of his civil rights activism there. Regarding the jazz discourse of the time, what gets reflected in the roundtables and in the curriculum of the school is that the big debate was this modernist versus traditionalist (“moldy fig”) culture war of the 1940s that extended into the 1950s. And Stearns essentially says that there is a bigger story to tell than this, that not enough work telling the backstory of jazz has been done. Where does this music come from? What are its pre-sources in other music we label something else, like blues, ragtime, or country music? So, he asks those kinds of questions in his writing and in the roundtables, and gets really focused, in particular, on the argument that jazz is a weaving together of African and European music in an American context. This is now pretty much accepted as a common understanding, but during the roundtables it was debated and conceptualized and argued over until it could fit into a one or two sentence definition. The idea that they had to come up with this definition had to do with academic politics and a need to summarize jazz into something like an abstract for a scholarly article.

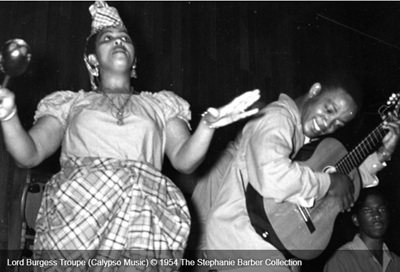

A key thing Stearns did during his career was to connect with scholars of Africa, and with scholars of the Afro-Caribbeans, which led him to an interest in African and Afro-Caribbean drumming. In one example, he went to Cuba in search of the story of the Cuban percussionist and singer Chano Pozo after his murder in New York not long after his important association with Dizzy Gillepsie. In the early years of the jazz roundtables at Music Inn, Stearns spotlights African and Caribbean drummers and West Indian calypsonians like Macbeth the Great. No other jazz critic of the time is as interested in what becomes known as Latin Jazz as Stearns.

JJM Where did someone like the traditionalist Rudi Blesh fit into this discussion?

JG Right. In his book Shining Trumpets, published in 1946, Blesh talks a lot about a kind of vague spirit of Africa infusing the blues and early jazz, but he has very little to say about actual Afro-diasporic musicians. And he marginalized himself by claiming that jazz had died in the late 1920s. So, he sort of writes himself out of the conversation, but comes back later after spending time at Music Inn, saying that small group jazz played by the likes of Ornette Coleman and Don Cherry revives the tradition of New Orleans collective polyphony.

JJM So Stearns enlarges the focus about what needs to be talked about regarding jazz…

JG Yes. About what can be understood about it in the context of the histories of movement of people, religion, and the social function of the music. He ended up writing a breakthrough book on jazz dance later on because he understood that dance is really central to African music, and continues to be central to other kinds of Black music – a claim few others were making at the time. He was alone among people writing about jazz in the 1950s, when Afro-Cuban jazz became popular, to look at the music not as for what jazz has become, but rather to see it as a new thing that is reviving and regenerating it. None of the revered critics of that moment, like Nat Hentoff, Martin Williams, or Leonard Feather – all of whom spent time in Lenox – are interested in that music. Stearns was also good at recruiting other academics from great universities to Lenox, bringing in literary critics, anthropologists, psychologists, etcetera, for three weeks in August to talk about the sociology of jazz.

JJM After all these years, what is Music Inn best remembered for?

JG Probably for its ability to bring so many people together, no matter their musical backgrounds. One example of what it will be remembered for is that Ornette Coleman and Don Cherry came there as students in the summer of 1959 right before the Ornette Coleman Quartet had its historic run at the Five Spot in the East Village, and right as its legendary Atlantic LP The Shape of Jazz to Come was released, which was seen as the lodestar of what was happening in jazz. Coleman and Cherry were at Music Inn on the Atlantic Records scholarship, which was part of the label’s recruitment strategy to get them to move from Los Angeles to New York and to record for Atlantic. Gunther Schuller was an important person in that strategy, and for a very brief period of time Martin Williams actually worked as Ornette’s manager in addition to writing important pieces on Ornette that would later be distilled into a chapter of his book The Jazz Tradition, which became the blueprint for the Smithsonian Collection of Classic Jazz.

So, imagine a school of jazz that welcomed incredible talent and teachers from all backgrounds who would go on to be pillars of jazz performance and education. George Russell, who was the godfather of the whole modal movement and a significant influence on Bill Evans, was part of Music Inn. Max Roach, who eventually teaches at UMass for a number of years, was also. David Baker comes as a trombone student and ends up starting a very important jazz studies program at Indiana University. The pianist Ran Blake spent four summers there, the school’s only four-year student. He and Jimmy Giuffre and George Russell become faculty members at the New England Conservatory when Gunther Schuller – also a faculty member at the Lenox School of Jazz – became its president and created its Third Stream and Contemporary Improvisation programs. All of this is an incredibly important part of the history of jazz education.

And finally, its legacy is that it made Black musicians the authority figures and mentors to white musicians during a time when a goal of integration was something as simple as making white people at least a little bit comfortable with the presence of Black people in their spaces – not that they were going to become the chosen leaders of their profession. But that was happening at Music Inn.

.

.

___

,

,

photo © Stephanie Barber/used by permission of author

.

Defining “jazz”

In 1951, after extensive deliberation, the Music Inn roundtable reached consensus on a streamlined definition of jazz consisting of a single sentence:

“Jazz is an improvisational American music, utilizing European instruments, and fusing elements of European harmony, Euro-African melody, and African rhythm.”

.

Several years later, in his book The Story of Jazz, Marshall Stearns revised the roundtable definition:

“We may define jazz tentatively as a semi-improvisational American music distinguished by an immediacy of communication, an expressiveness characteristic of the free use of the human voice, and a complex flowing rhythm; it is the result of a three-hundred-years blending in the United States of the European and West African musical traditions, and its predominant components are European harmony, Euro-American melody, and African

rhythm.”

Notable here was an emphasis on the epochal history of

transatlantic cultural blending and a more powerful illumination of

the music’s dynamism and pulse through such terms as “immediacy,” “expressiveness,” and “flowing.”

-John Gennari

.

.

Listen to the 1958 recording of the Modern Jazz Quartet (with Sonny Rollins) performing Milt Jackson’s composition “Bags’ Groove,” with John Lewis (piano); Jackson (vibes); Percy Heath (bass); Connie Kay (drums); and Rollins (tenor saxophone). [Rhino/Atlantic]

.

.

_____

.

.

.

Critical acclaim for the book

Gennari connects place, race, and music in a local story with global significance. He writes with the insights of a master writer, a jazz soloist who understands tone, rhythm, and the enlightening elegance of a thing well done. The remarkable photographs give us additional insights into the story.

Benjamin Cawthra

Author of Blue Notes in Black and White: Photography and Jazz

.

This is jazz history at its best. John Gennari tells a fascinating story about a moment in the music’s history that is as essential as it is uncelebrated. This highly recommended book is as thoroughly researched as it is engaging.

Krin Gabbard

Author of Better Git It in Your Soul: An Interpretive Biography of Charles Mingus

.

John Gennari’s book encourages one to see the former jazz barn, not as a relic of the past but the source of so much we consider normal today. I’m delighted and enriched by his restorative and significant book.

Darius Brubeck

from the book’s Foreword

.

A brilliant meditation on art, place, and the political imagination as they entwined to the sound of jazz in postwar New England. Dazzling cultural analysis slyly delivered as a lively untold story.

David Hajdu

Professor at Columbia University and author of Love for Sale: Popular Music in America

.

.

___

.

.

About John Gennari

John Gennari is Professor of English and Critical Race and Ethnic Studies at the University of Vermont. Gennari’s previous book, Flavor and Soul: Italian America at Its African American Edge (University of Chicago Press, 2017), is a study of Black/Italian cultural intersections in music and vernacular soundscapes, foodways, sports, and other forms of expressive culture. His earlier book, Blowin’ Hot and Cool: Jazz and Its Critics (University of Chicago Press, 2006), won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for Excellence in Music Criticism and the John G. Cawelti Award for Best Book in American Culture Studies.

.

.

_____

.

.

This interview took place on November 25, 2025, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita

.

.

.

_____

.

.

Click here to read the 2006 Jerry Jazz Musician interview with John Gennari about his book Blowin’ Hot and Cool: Jazz and its Critics

.

Click here to read other interviews published on Jerry Jazz Musician

Click here to subscribe to the (free) Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter

Click here to help support the ongoing publication of Jerry Jazz Musician, and to keep it commercial-free (thank you!)

.

___

.

.

Jerry Jazz Musician…human produced (and AI-free) since 1999

.

.